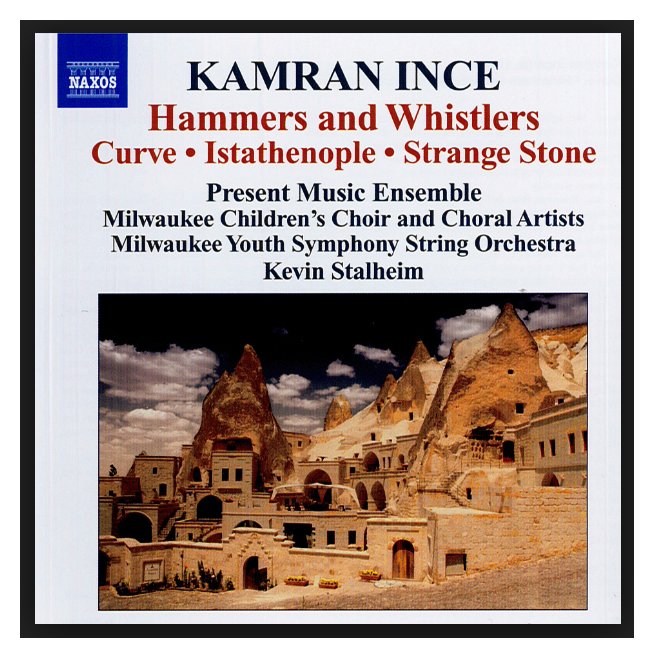

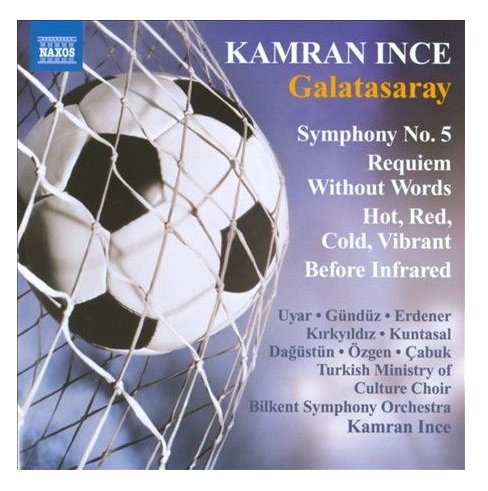

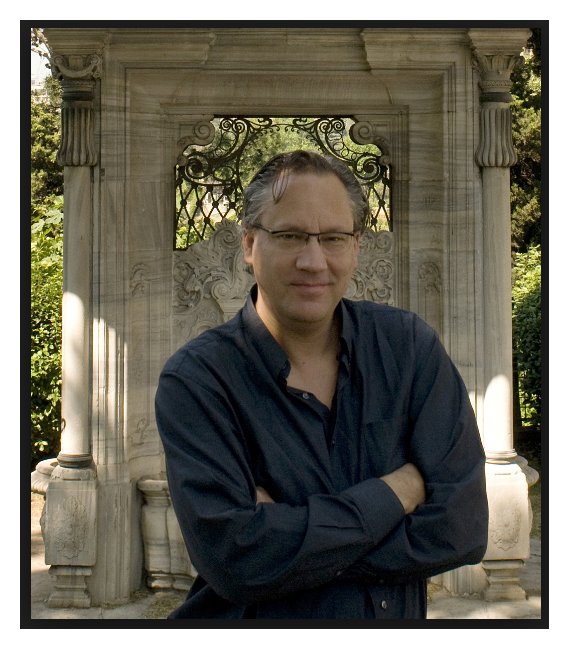

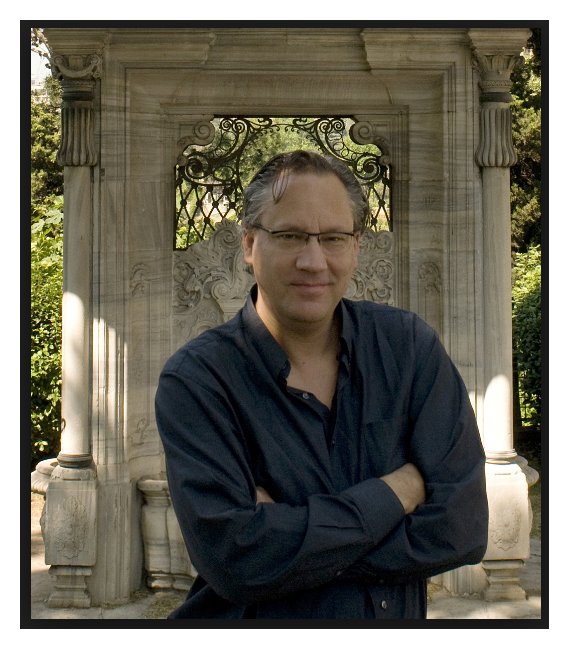

Composer Kamran Ince

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Kamran Ince was born in Montana

in 1960 to American and Turkish parents. He holds a Doctorate from

Eastman School of Music, and currently serves as Professor of

Composition at University of Memphis and Co-Director of MIAM (Center

for Advanced Research in Music) at the Istanbul Technical University.

The leading orchestras of the world perform his works. Concerts devoted

to his music have recently been heard at the Holland Festival, CBC

Encounter Series (Toronto), the Istanbul International Music Festival,

Estoril Festival (Lisbon), TurkFest (London), and Cultural Influences

in Globalization Festival (Ho Chi Minh City). In addition to symphonic

and chamber works, his catalogue also includes music for film and

ballet. His numerous prizes include the Prix de Rome, the Guggenheim

Fellowship, and the Lili Boulanger Prize. His Waves of Talya was named

one of the best chamber works of the 20th Century by a living composer

in the Chamber Music Magazine.

His music is published by Schott Music

Corporation.

|

In October of 1989, Kamran Ince was not quite thirty. He was

having his work Before Infrared

played by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on one of its regular

subscriptions series. Surrounded by music of Mozart (Piano Concerto #21) and Falla (Nights in the Gardens of Spain)

with Alicia De Larrocha, and La Mer

of Debussy, it stood its own and was warmly received. David

Zinman conducted.

Besides what is shown in the box above, he studied with (among others)

Joseph Schwantner, Christopher Rouse, Samuel Adler, and Barbara

Kolb. [See my Interview with

Joseph Schwantner, my Interview with

Christopher Rouse, and my Interview with Samuel

Adler.] Now, a quarter-century later, Ince has lived up to

his promise, and taken his place in the group of composers whose works

are regularly performed and recorded.

We met for the interview at the end of a long day, and while he was

perfectly willing to chat, he was tired and mentioned that as we began

. . . . . . .

Kamran Ince:

I’m not that vibrant. I’m

kind of tired.

Bruce Duffie:

Is your music at all tired, or is your

music always vibrant?

KI:

[Laughs] It’s very seldom tired, I would

say. It’s mostly vibrant. But my music from three or four

years ago was much more vibrant. I’ve just finished a septet for

this ensemble in New York. They’re going to play it next month,

and it’s very laid back and very quiet, but yet, it’s contrasted by

incredible outbursts of energetic and odd-sounding stuff. This

summer I was listening to Ennio Morricone, the film composer, a

lot. I was affected by

these very simple, twisted Italian melodies. So in this latest

piece I was going for something kind of simple, effortless, and kind of

timeless. It sounds so grand.

BD: How does

someone who is merely twenty-nine years

old get a piece played by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra?

KI: Well, if

a conductor wants to do a piece, and if

the circumstances work out, then he’ll take it to

where he wants to perform it. Zinman wanted to do it.

Actually he was going to do it in Baltimore last year, but they were

on strike, so he’s doing it here and then next year in Baltimore and

then New York.

BD: So he

must have heard your music before

this, and believed in you?

KI: Yes, he

did hear my music. He

knows my music.

BD: Is this

what a composer has to do

— find a conductor who will champion

the music?

KI: Oh, it

definitely helps, yes. Definitely

helps, undoubtedly.

BD: Was this

piece on commission, or is this a

piece you wrote and submitted?

KI: Actually, no. I

had written another piece called Infrared

Only that was for a

commission for the New York Youth Symphony. I wrote it when I was

twenty-five, and it was done in New York when I

was twenty-six. It’s a very energetic

piece with high action, and I wanted to write a second piece

that will somehow take me to that piece. This way they can go

together. It’s a twenty-minute work, or they can be played

separately, as Infrared Only

and Before Infrared.

KI: Actually, no. I

had written another piece called Infrared

Only that was for a

commission for the New York Youth Symphony. I wrote it when I was

twenty-five, and it was done in New York when I

was twenty-six. It’s a very energetic

piece with high action, and I wanted to write a second piece

that will somehow take me to that piece. This way they can go

together. It’s a twenty-minute work, or they can be played

separately, as Infrared Only

and Before Infrared.

BD: You’re

not going to

write third piece and make it a trilogy?

KI: No.

But so far they have

been played separately. Actually, the Brooklyn Philharmonic will

play it together, maybe next year or a year later. They’re

supposed to, anyway.

BD: Let me

get a little background about you. I

assume you didn’t start out

composing. You probably started out playing an instrument?

KI:

Yes. I started out with cello when I was

about ten.

BD: When did

you decide that you wanted to be a

creator rather than a re-creator?

KI: Before

that I was playing the

mandolin. This was in Turkey, in Ankara. I like

to improvise. I was a kid and I didn’t know

what I was doing. But then I started playing cello, and my father

saw that I was improvising so he

encouraged me. Then I started doing a little bit more and

developed

that way.

BD: You then

studied back here in the

United States?

KI:

Yes. I actually started in

Turkey. I went to the conservatory after elementary school.

That’s how the system works there. Then you go through

university, and when I was in university I transferred to

Oberlin. I finished there and then I went to Eastman School

of Music where I got my doctorate two years ago.

BD: When

you’re sitting down to write a piece,

are you at the stage yet where everything is under your control, or are

there still times when that pencil really is controlling your

hand and you follow it?

KI: No, I am

in control. Actually, that

problem sometimes exists for composers. When they compose at the

piano, then they write where their fingers take

them. But I have total control. Sometimes you

get so passionate that you may not think about things too much and do

something more intuitive. I like to do it

intuitively. I like to compose. I believe in

intuition and passion.

BD: Are you

ever surprised where your

composition winds up?

KI: How do

you mean?

BD: When you

start writing, do you know how it’s

going to sound when you get to

the end?

KI: In some

cases I know a

general shape, and in other cases, no. I start out with a

striking idea from myself, and then that kind of takes me,

and I discover as I go along. That’s the exciting thing for

me most of the time, because if I knew what was going to happen, it

would be boring for me to spend all those hours.

This way I can go to bed and wake up still thinking about it.

BD: Is the

act of composing something

that is laborious?

KI:

Sometimes, it can be, yes. Sometimes

you may not necessarily want to, but you must create every day for

three or four hours. That’s what I

do. I guess some people can create for seven

or eight hours, but that’s my limit pretty much, four hours or

so. But every day you must do it

because you’re working with deadlines. That’s your work; you must

do it every

day. Sometimes you are very excited, and other days you

may not be as excited, but you know you have to work. But yet,

what comes out might still be even more exciting, even if you weren’t

excited while doing it. [Laughs]

BD: You spend

every day

composing. Do you have any other form of employment, or are you

living on your commissions?

KI: Yes, I’m

living on my grants and

commissions, etcetera.

BD: I assume

you are getting

enough of them, then, to hold body and soul together?

KI: For the

time being, yes.

BD: Are you

getting, perhaps, too many, so that you

turn

some down?

KI: No, no.

BD: So

anything that comes to you, you

will accept?

KI: Oh,

yes! I do.

BD: If

someone comes to you with a commission for

a trio for piccolo, ocarina, and tuba, you will do it?

KI: Uh!

[Laughs] If they pay a lot of

money, yes, I’ll do it.

BD:

Really??? You’d be able to crank your

musical mind into a

mode that you’re not familiar with, or not even enthusiastic about?

KI: Maybe

there’s something. Maybe there’s

something to pairing the piccolo and tuba that I don’t know.

BD: [With a

gentle nudge] Don’t

forget the ocarina!

KI: What is

that instrument? I don’t know it.

BD:

[Surprised] Oh! So you’d have to

learn a little

bit. It’s like a sweet potato with holes in it.

KI: [Laughs]

Oh, okay. Well yes, I think I

would even do that! Sure. I don’t think even money

is important. I think I will do it if I have the

time, and if I can fit it in somewhere.

BD: When you get a commission,

do you know in

advance about how long it will take to complete the work?

BD: When you get a commission,

do you know in

advance about how long it will take to complete the work?

KI: I have an

idea. The more you write

commissioned pieces, the more you know how long it takes you to write

them. But coming back to the money point, sometimes

something that I really like may not involve much money, and

I’ll do it because I really like it.

BD: In your

young career, have you already written for all forms

— chamber, symphony, band, etcetera?

KI:

Yes. Well no, I haven’t written for

bands.

BD: String

quartet?

KI: When I

was fourteen or fifteen I wrote for string

quartet, but that was obviously a learning piece. I have written

for orchestra, chamber, piano, two instruments, piano and

something else, etcetera.

BD: Does it

help if you play the instrument yourself,

to get some better ideas or compositional techniques needed on the

paper?

KI: No, not

at all. Actually,

sometimes it’s better that you not play the instrument because you’re

not as conditioned to think in certain ways. When you were

learning on an instrument you don’t take chances necessarily, but with

an instrument you don’t know, you take more

chances. Writing for the orchestra and for all these

different ensembles, you develop a knowledge for all the instruments,

really. You know what they can do and what they can’t do,

and what they’re best at.

BD: Are you

mostly concerned with simply the

end product, the sound that comes out? Is that really all that

concerns you, rather than the technique of producing that sound?

KI: You mean

whether I’m more concerned with the

process or the result?

BD: Mm-hm.

KI: Of

course, the result. I don’t care what

the process is.

BD: You don’t

care if the cello player stands on his

head, and then bows the back of the instrument?

KI: Oh,

no! I wouldn’t ask them to do awkward

things. I don’t believe in that.

I thought you were talking musically.

BD: Even if

it produces just the sound you want?

KI: Standing

on the head? What kind of sound

would that be?

BD: I have no

idea, but you’re the composer.

[Both laugh] I’m creating a few hypothetical

situations.

KI: Like for

instance going into the piano you can

get great sounds, and yes, I’ve used that many times.

BD: I’m

looking for the compositional process, which

is hard to pin down.

KI:

Yes. As I said, I start with an idea,

and then I develop from there. You

must work every day, but sometimes when I have the

time, I say I cannot work. I must somehow re-group, come back and

view what I was doing from an independent point of view after a couple

of days passed. Then,

maybe, whatever was going to come

after or how I was going to develop the idea has ripened in my

mind. Then I’ll go back to

it. There’s times like that, too. There’s even times where

I find it

very useful not to compose for, let’s say, a month.

BD: To clear

your mind?

KI: Oh yes,

because a

lot of times you get into a routine. You are able to pull back

and look at it, but sometimes you need more time to pull back and

refresh what you are and regroup

that creative power. Maybe every two years I find myself needing

to rest for a month.

BD: When

you’re working on a piece

and you get all of the notes down and you’re polishing and you’re

tinkering, how do you know when to put the pencil down

and say, “It is finished. It is ready to go.”?

KI: I don’t

do any sketches. What I write down,

that’s the

last score on the paper because I don’t like to copy afterwards,

either. I work with a very dark pencil, so whatever I write down

is permanent for the time being, and if I want to

change it, I can go back and totally erase it.

BD: So you

try to get it complete in

your mind before it goes on the paper?

KI: Yes, I

do. Sometimes it works very

well, and sometimes I must later on come back and insert things or

take out things or maybe erase totally.

BD: Do you

ever go back and revise a score once it’s

been played?

KI: No, I

haven’t really done that. Sometimes

if it’s chamber music and you know the group pretty

well — or

even if you don’t know them and they perform it for the first

time — you

see that some things don’t work. Right on the spot

as they’re rehearsing you say, “Okay, why don’t you try this, or try

that, or do this?” If those work, then yes, I go back and change

them after the performance. Also with tempos

that’s very possible, too.

BD: Are there

ever times when the

performers find things in your score that you didn’t know were there

— little hidden brilliances or

something like that?

KI: Well, not

really hidden

brilliances, but more like hidden feelings that I may not have

felt. Sometimes that

happens. I was talking to John Corigliano the other

day in the ballroom here at Orchestra Hall, and he analyzed this piece

and then came out with some things. [Note: Corigliano was at that

time Composer-in-Residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

See my Interviews

with John Corigliano.] For instance, apparently

the piece starts with one

note and then slowly other notes get added. Apparently I

used eleven notes and don’t use the twelfth note. When the

melody comes in, then I use the twelfth note in the bass. This is

something I hadn’t thought of.

BD: So you

don’t work

from theory; the theory comes afterward?

KI:

Exactly. When I was

doing my masters, I had to write a thesis on my piano concerto, and I

found things that I could not believe. They were really

incredible!

BD: Good

things or bad things?

KI: Very good

things. I couldn’t believe how

everything

clicked, and how everything made sense. Corigliano was saying

that he did the same thing with

a piece of his, and the same thing happened.

BD: So it’s

more intuition

than technique?

KI:

Yes. My intuition is translated through my

technique onto the

paper. I don’t say before I sit down, “Okay, I’ll

use these, these, these, these pitches, and then I will never use these

pitches,” or, “I’ll use this rhythm

strictly, and then I’ll mathematically permutate that and do

things.” I don’t work that way, but some composers do. I

don’t like

that. It’s not exciting for me.

BD: Composing

the way you compose is

exciting for you?

KI:

Yes. It is exciting, yes.

*

* *

* *

BD: Let me

ask the great, big philosophical

question. What is the purpose of music in society?

KI: Maybe it

is to take them to

places that we cannot explain or to make them feel

things that we cannot put our fingers on, such as emotions. Music

can whip so many things in me and I’m sure in

other people, too — places,

times, memories, déjà

vus, unexplainable moods, joy, happiness, excitement, that

secret world.

BD: Is it your secret world

that we

are going into, or are you taking us into the secret world?

BD: Is it your secret world

that we

are going into, or are you taking us into the secret world?

KI: No, it is

my

world. Of course it’s probably part of the

secret world, but it’s my world. Every

composer’s world, every individual’s world, is part of the whole

world.

BD: Do you

feel that you are part of a lineage

of composers stretching back through the centuries?

KI: Oh,

sure. Oh, sure, definitely!

Yes. Yes. Yes. [Laughs]

BD: Are you

pleased with the way this

particular piece is sounding with this particular orchestra?

KI: Yes, very

much so, because there’s a

lot of brass and there’s a lot of bright woodwinds.

BD: If you

get a commission for a

group that is not technically so proficient, would you write something

that is moving but yet technically easier?

KI: Oh, yes,

sure! But I am very

pleased with the performance here. David Zinman is doing a super

job. He’s great. He’s so precise.

BD: You’ve

got several commissions that you’re working on now.

How far ahead are the deadlines that you’ve already agreed?

KI: Maybe

middle of ‘91.

BD: Is that a

good feeling to know that in the

middle of ‘91 you’ll have this piece completed and hear it performed?

KI:

Yes. It will be a good feeling if I’m

really pleased with the

piece, which I hope to be.

BD: Is there

ever a case where you get part way in

the piece and decide it’s no good and just scrap it?

KI: No.

I never felt that

way, but if I did feel that way, I would do it, I think. On

the other hand, you go through periods with every piece, and afterwards

you’re not necessarily terribly

impressed by it as when you were writing it. But that’s true

about all art work. After some time passes you reconsider.

Then with some pieces you’re much more pleased

and you’re really proud of them, and some pieces you’re not as

much. Maybe that’s exciting, too.

BD: What do

you expect of the audience

that comes to hear a piece of yours?

KI: I would

like the audience to be

involved with every measure of the music, and be somehow moved or not

moved. I hope they have some kind of reaction to every measure of

the music. I my music I would like to keep the attention of the

audience at every moment, and somehow grab them with that world

and take them through it, and then let them breathe only at the

end.

BD: Is it

supposed to be an artistic

enrichment, or is it supposed to be entertaining?

KI:

Definitely artistic enrichment, but they’re

entertained in the process, which I’m sure they will be if it’s an

artistic enrichment.

BD: Where is

this delicate balance between the art

and the entertainment?

KI: Who

knows? Obviously there’s

some entertainment and artistic enrichment in all classical

music. One would think that if they’re entertained, if they

really like the piece, they’re enriched. They’ve gone into this

world, and I

have made them think things they may not have thought and felt

before. Would you call that entertainment? It would be, I

guess.

*

* *

* *

BD: You’re an

American, or you’re Turkish, or

what?

KI: I’m both. My mother’s

American and my father’s Turkish. I live half my life there and

half

my life here. I’m living in America, so I’m an

American.

KI: I’m both. My mother’s

American and my father’s Turkish. I live half my life there and

half

my life here. I’m living in America, so I’m an

American.

BD: Is there

anything particularly Turkish that wends

its way through your music?

KI: No.

Subconsciously I have an

affinity for contrasts, so that comes from not only Turkish music, but

this bi-cultural-ness that I am, having been

exposed to two drastically different cultures.

BD: Is it at

all difficult to put these two

drastically different cultures together?

KI: I’ve been

coping with that within myself all my

life within myself, not just in my music. Actually it gives

me an advantage, and an edge to my music,

probably. But as far as my personality and my inner worlds, I’ve

finally come in terms with that. I’m

bi-cultural and I’m finally comfortable with that. But

also I lived a year in Italy, in Rome, which was a very odd

thing. I had the Prix de Rome, the Rome Prize, and that was very

hard. I was born here in America, and I left to go to Turkey when

I

was

seven. When I got there, all the kids made fun of me. They

called me ‘the

American’.

I went to

school and felt comfortable, then I came back here when I was

twenty.

BD: Then here

you were ‘the

Turk’?

KI: For a

while, yes, and I couldn’t adjust.

Then finally I did, and finally I felt at home in America. I

liked everything about it. Then I went to Italy for a year.

I was mostly an

American in Italy, but somehow, being in Europe I was close to Turkey

there. I felt like I was no one,

basically, because a year is a kind of odd time. Are you a

tourist? Are you Italian? What are you? You

don’t speak the language well. By the time you get used to it,

you leave. Then I came back to America, and now,

finally, I think I’m back into feeling and being very comfortable as an

American.

BD: Let me

take you back to Turkey just for a

minute. What is the cultural life like in Ankara?

KI: I was

also in Izmir,

too. Ankara is the capital. It’s very organized. They

have a good orchestra. They have opera. They have great

theaters. Theater is something very strong in Turkey.

BD: Is the

opera done in Turkish, or in the language

that it’s written?

KI: Mostly in

Turkish, unless it’s

in Italian.

BD: Is

Italian close to the Turkish language?

KI: Not at

all. I guess they want to please the

singers or

something like that. [Laughs] In Ankara there are all the

embassies and everything. My mother’s American, so we spoke two

languages at home. But life is not bad in

Ankara.

BD: Thank you

so much for coming to Chicago and for

speaking with me.

KI:

Yes. Great, great. You do a great

job!

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 13,

1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following

year,

and again in 1995 and 2000; on WNUR in 2009 and 2010, and on

Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2009.

This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until

its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His

interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980,

and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well

as

on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

KI: Actually, no. I

had written another piece called Infrared

Only that was for a

commission for the New York Youth Symphony. I wrote it when I was

twenty-five, and it was done in New York when I

was twenty-six. It’s a very energetic

piece with high action, and I wanted to write a second piece

that will somehow take me to that piece. This way they can go

together. It’s a twenty-minute work, or they can be played

separately, as Infrared Only

and Before Infrared.

KI: Actually, no. I

had written another piece called Infrared

Only that was for a

commission for the New York Youth Symphony. I wrote it when I was

twenty-five, and it was done in New York when I

was twenty-six. It’s a very energetic

piece with high action, and I wanted to write a second piece

that will somehow take me to that piece. This way they can go

together. It’s a twenty-minute work, or they can be played

separately, as Infrared Only

and Before Infrared.  BD: When you get a commission,

do you know in

advance about how long it will take to complete the work?

BD: When you get a commission,

do you know in

advance about how long it will take to complete the work? BD: Is it your secret world

that we

are going into, or are you taking us into the secret world?

BD: Is it your secret world

that we

are going into, or are you taking us into the secret world? KI: I’m both. My mother’s

American and my father’s Turkish. I live half my life there and

half

my life here. I’m living in America, so I’m an

American.

KI: I’m both. My mother’s

American and my father’s Turkish. I live half my life there and

half

my life here. I’m living in America, so I’m an

American.