SA: That’s

right. If a piece is worth

playing twice or twenty times, there’s a growth in it. I’ve been

lucky in writing pieces for people like the Cleveland Quartet, the

Pro Arte Quartet and the great Fine Arts Quartet when they were still

in Chicago. I wrote two

quartets for them, my Fourth

and my Sixth Quartet, and

both those

quartets they took all over the world. The Sixth Quartet was

premiered here in Chicago at the Goodman Theater with Jan de Gaetani,

and they recorded it afterwards. It was different when they came

back from Europe. I heard it again in New York or in

Washington, but it was different because

there was a relaxation; not slower — I’m talking about a relaxed

attitude towards the piece because all the complexities had been

overcome.

SA: That’s

right. If a piece is worth

playing twice or twenty times, there’s a growth in it. I’ve been

lucky in writing pieces for people like the Cleveland Quartet, the

Pro Arte Quartet and the great Fine Arts Quartet when they were still

in Chicago. I wrote two

quartets for them, my Fourth

and my Sixth Quartet, and

both those

quartets they took all over the world. The Sixth Quartet was

premiered here in Chicago at the Goodman Theater with Jan de Gaetani,

and they recorded it afterwards. It was different when they came

back from Europe. I heard it again in New York or in

Washington, but it was different because

there was a relaxation; not slower — I’m talking about a relaxed

attitude towards the piece because all the complexities had been

overcome. SA: What is enough

time? [Both laugh] After all, we never have enough time to

compose! I love to teach, and I have the

most wonderful students. My students turn me on. In the

forty years that I’ve been teaching, I am enjoying

teaching now more than ever, this year especially. We have

thirteen

freshmen who are fantastic! It is just wonderful to see these young men

and women so

eager and so exciting, and so talented; more talent than perhaps

I’ve ever seen before. They’re determined, and that’s very

good. Coming back to your question, no, some people can’t teach

and compose at the same time. It

doesn’t sit with them. If it weren’t for how much time my

duties at school take, it would be better to have more time to

compose. But it’s very inspiring to work with young minds all the

time. It’s very challenging, and it’s good for me. I feel

it’s good for me as a composer. It “turns me on.” Of course

I would like to have more time, but I’m old enough that I’m almost

ready for retirement, and when I retire in a couple of years I will

have more time.

SA: What is enough

time? [Both laugh] After all, we never have enough time to

compose! I love to teach, and I have the

most wonderful students. My students turn me on. In the

forty years that I’ve been teaching, I am enjoying

teaching now more than ever, this year especially. We have

thirteen

freshmen who are fantastic! It is just wonderful to see these young men

and women so

eager and so exciting, and so talented; more talent than perhaps

I’ve ever seen before. They’re determined, and that’s very

good. Coming back to your question, no, some people can’t teach

and compose at the same time. It

doesn’t sit with them. If it weren’t for how much time my

duties at school take, it would be better to have more time to

compose. But it’s very inspiring to work with young minds all the

time. It’s very challenging, and it’s good for me. I feel

it’s good for me as a composer. It “turns me on.” Of course

I would like to have more time, but I’m old enough that I’m almost

ready for retirement, and when I retire in a couple of years I will

have more time. SA: There’s

only joy. One of the great

joys of my life is to write for voice, and even to write for chorus,

though sometimes you hear a piece badly done because they can’t do

it. But you see the joy of human communication

because that is the depth of it. I’ve been very lucky because

my music has been performed by people like Jan DeGaetani and Tom Paul,

and great young singers. It’s very

exciting, what’s happening in the vocal world today, and

with choruses, too. We have fantastic choruses and college choirs

that can sing better than any professional group. I’ve been lucky

in that way; my pieces have been

performed by excellent organizations. That is a great joy

because, after all, the voice is the most human thing. There is

no

intermediary. There is no instrument that you play on. But

I have to confess to you that any medium that I write for at the moment

is my favorite. I don’t say that I’d rather write songs or write

for the voice than for anything else. I just love music,

and I love to write.

SA: There’s

only joy. One of the great

joys of my life is to write for voice, and even to write for chorus,

though sometimes you hear a piece badly done because they can’t do

it. But you see the joy of human communication

because that is the depth of it. I’ve been very lucky because

my music has been performed by people like Jan DeGaetani and Tom Paul,

and great young singers. It’s very

exciting, what’s happening in the vocal world today, and

with choruses, too. We have fantastic choruses and college choirs

that can sing better than any professional group. I’ve been lucky

in that way; my pieces have been

performed by excellent organizations. That is a great joy

because, after all, the voice is the most human thing. There is

no

intermediary. There is no instrument that you play on. But

I have to confess to you that any medium that I write for at the moment

is my favorite. I don’t say that I’d rather write songs or write

for the voice than for anything else. I just love music,

and I love to write. SA: There is not

that much recorded. I see you

have the Madrigals, which are

wonderful on the Chanukah record [on Golden Crest]. Those are

beautiful pieces, and I am happy about

the recording. It’s very good. [He then picked up a Gasparo disc by

organist Barbara Harbach, which included his Hymnset.]

How Firm a

Foundation they’ll love, because they’ll know that piece.

The

others are American folk tunes. Then there’s an arrangement of

Bill

Schumann’s When Jesus Wept,

which was done in a very funny

way. [See my Interview

with William Schuman.] You know, composers have experiences

with other

composers. After my Organ

Concerto was played by Leonard Raver and the Portland, Maine,

Symphony, Leonard said to me, “I’m trying to get Bill Schuman to

write a piece for organ.” Sometime later I had lunch at Bill’s

and we were talking about it. Bill

said, “I don’t like organ, and I just don’t want to write

it.” I said, “You already have a piece; you just have to

arrange it. If you take the second movement of the New England

Triptych, it would make a perfect organ piece.” We

continued to eat our lunch, and all of a sudden we got to dessert and

he said, “You

know, I have a big birthday coming up. How about you doing the

arrangement?” And I did! So, it was a birthday present.

SA: There is not

that much recorded. I see you

have the Madrigals, which are

wonderful on the Chanukah record [on Golden Crest]. Those are

beautiful pieces, and I am happy about

the recording. It’s very good. [He then picked up a Gasparo disc by

organist Barbara Harbach, which included his Hymnset.]

How Firm a

Foundation they’ll love, because they’ll know that piece.

The

others are American folk tunes. Then there’s an arrangement of

Bill

Schumann’s When Jesus Wept,

which was done in a very funny

way. [See my Interview

with William Schuman.] You know, composers have experiences

with other

composers. After my Organ

Concerto was played by Leonard Raver and the Portland, Maine,

Symphony, Leonard said to me, “I’m trying to get Bill Schuman to

write a piece for organ.” Sometime later I had lunch at Bill’s

and we were talking about it. Bill

said, “I don’t like organ, and I just don’t want to write

it.” I said, “You already have a piece; you just have to

arrange it. If you take the second movement of the New England

Triptych, it would make a perfect organ piece.” We

continued to eat our lunch, and all of a sudden we got to dessert and

he said, “You

know, I have a big birthday coming up. How about you doing the

arrangement?” And I did! So, it was a birthday present. BD: If

someone comes to you and wants something that you don’t like, would you

turn it down or would you try to wrestle with it?

BD: If

someone comes to you and wants something that you don’t like, would you

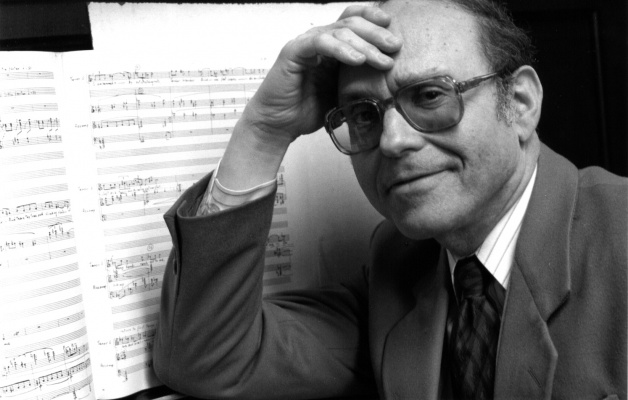

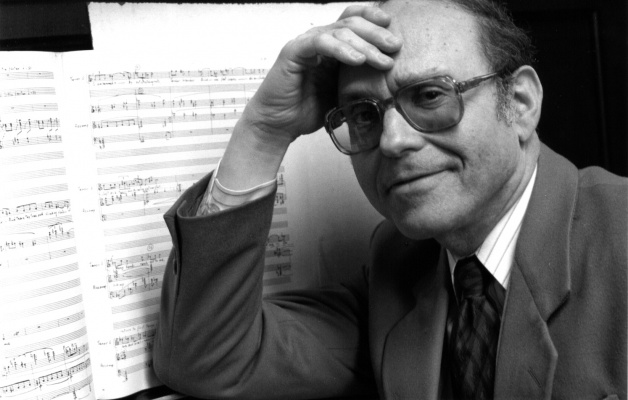

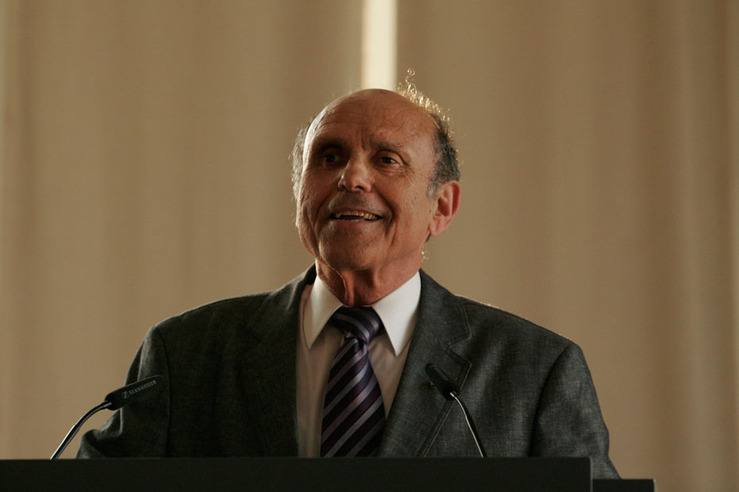

turn it down or would you try to wrestle with it?| Adler, Samuel (b. March 4, 1928,

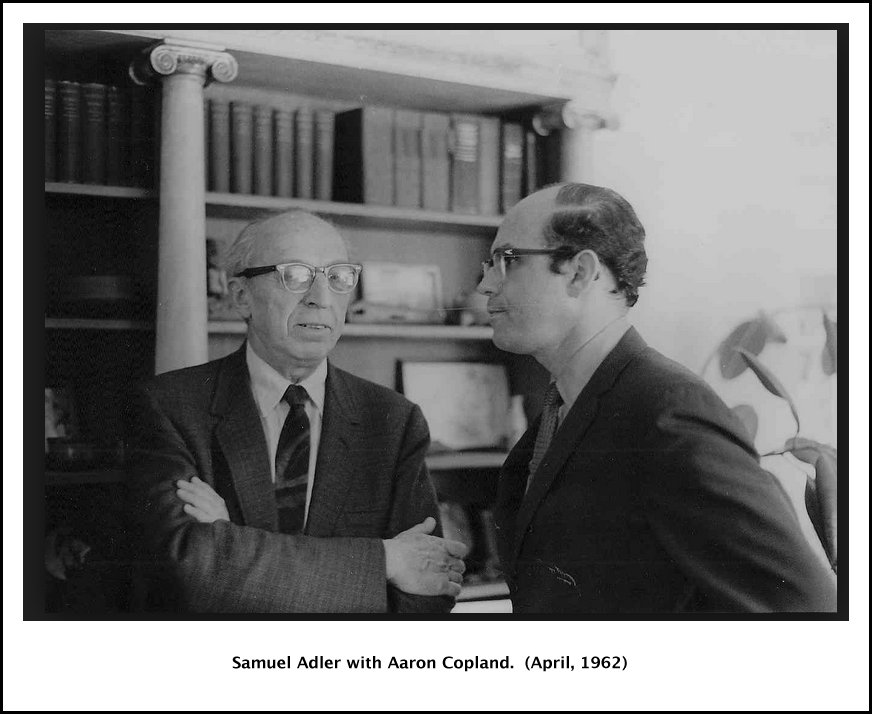

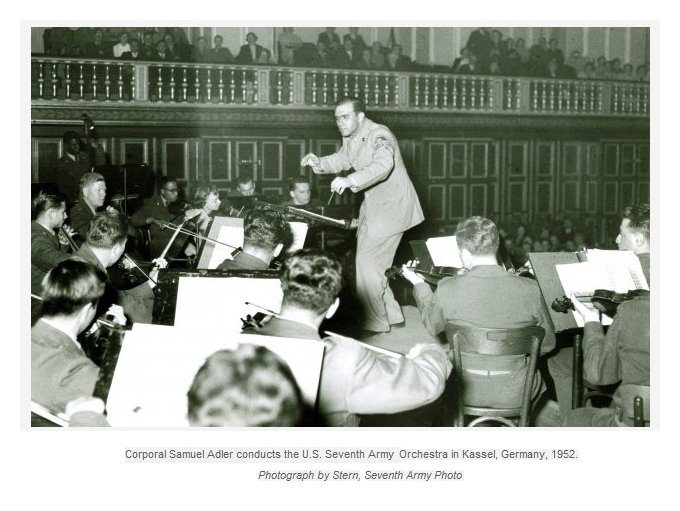

Mannheim). German-born American composer of mostly stage, orchestral,

chamber, choral, vocal, piano, and organ works that have been performed

throughout the world; he is also active as a conductor. Prof. Adler is the son of cantor-composer Hugo Adler, who moved the family to the USA in 1939. He studied violin with Albert Levy as a child and later studied composition with Herbert Fromm and Hugo Norden at Boston University, where he earned his BMus in 1948. He then studied with Aaron Copland, Paul Hindemith, Paul Pisk, Walter Piston, and Randall Thompson at Harvard University, where he earned his MA in 1950, and also studied conducting with Sergey Koussevitzky at Tanglewood in 1949. He received honorary doctorates from the St. Louis Conservatory, St. Mary's Notre-Dame, Southern Methodist University, and Wake Forest University from 1968-79. Among his honors are the Army Medal of Honor (1953, for his organization of the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra), the Charles Ives Living Prize (1961), the Lillian Fairchild Award (1974), and the Deems Taylor Award (1983, for The Study of Orchestration). Other honors include the Composer of the Year Award from MTNA (1988-89), the Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1990) and the Special Citation from the American Foundation of Music Clubs (2001). He has received grants from the Rockefeller (1965) and Ford (1966-71) foundations, as well as five MacDowell fellowships (1954-55, 1957, 1959, 1964) and one Guggenheim Fellowship (1975-76). He has been a member of the Academia Chilena de Bellas Artes since 1993, the Akademie der Künste in Mannheim since 1999 and the American Academy of Arts and Letters since 2001. As a conductor, he has led orchestras throughout the USA and conducted the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra in Europe from 1950-52. He served as music director at Temple Emanu-El in Dallas from 1953-66 and of the Dallas Chorale and Dallas Lyric Theater from 1954-58. His books are Anthology for the Teaching of Choral Conducting (1971, Holt, Reinhart and Winston; second edition, 1985, Schirmer Books), Sight Singing (1979, second edition, 1997, W.W. Norton) and The Study of Orchestration (1982, second edition, 1989, third edition, 2001, W.W. Norton). He taught Fine Arts at the Hockaday School in Dallas from 1955-66 and taught as a professor of composition at North Texas State University from 1957-66. He then taught at the Eastman School of Music from 1966-95, where he served as chair of the composition department from 1974-95 and retired as professor emeritus, and has taught at the Juilliard School since 1997. He has given lectures throughout the Americas and in Asia and Europe and served as the Honorary Professorial Fellow at the University College in Cardiff in 1984-85. In addition to his original compositions, Prof. Adler has made numerous arrangements and has written didactic music. |

|

Samuel Adler was born March 4, 1928, Mannheim, Germany and came to the United States in 1939. He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in May 2001, and then inducted into the American Classical Music Hall of Fame in October 2008. He is the composer of over 400 published works, including 5 operas, 6 symphonies, 12 concerti, 8 string quartets, 4 oratorios and many other orchestral, band, chamber and choral works and songs, which have been performed all over the world. He is the author of three books, Choral Conducting (Holt Reinhart and Winston 1971, second edition Schirmer Books 1985), Sight Singing (W.W. Norton 1979, 1997), and The Study of Orchestration (W.W. Norton 1982, 1989, 2001). He has also contributed numerous articles to major magazines and books published in the U.S. and abroad. Adler was educated at Boston University and Harvard University, and holds honorary doctorates from Southern Methodist University, Wake Forest University, St. Mary’s Notre-Dame and the St. Louis Conservatory. His major teachers were: in composition, Herbert Fromm, Walter Piston, Randall Thompson, Paul Hindemith and Aaron Copland; in conducting, Serge Koussevitzky. He is Professor-emeritus at the Eastman School of Music where he taught from 1966 to 1995 and served as chair of the composition department from 1974 until his retirement. Before going to Eastman, Adler served as professor of composition at the University of North Texas (1957-1977), Music Director at Temple Emanu-El in Dallas, Texas (1953-1966), and instructor of Fine Arts at the Hockaday School in Dallas, Texas (1955-1966). From 1954 to 1958 he was music director of the Dallas Lyric Theater and the Dallas Chorale. Since 1997 he has been a member of the composition faculty at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City, and was awarded the 2009-10 William Schuman Scholars Chair. Adler has given master classes and workshops at over 300 universities worldwide, and in the summers has taught at major music festivals such as Tanglewood, Aspen, Brevard, Bowdoin, as well as others in France, Germany, Israel, Spain, Austria, Poland, South America and Korea. Some recent commissions have been from the Cleveland Orchestra (Cello Concerto), the National Symphony (Piano Concerto No. 1), the Dallas Symphony (Lux Perpetua), the Pittsburgh Symphony (Viola Concerto), the Houston Symphony (Horn Concerto), the Barlow Foundation/Atlanta Symphony (Choose Life), the American Brass Quintet, the Wolf Trap Foundation, the Berlin-Bochum Bass Ensemble, the Ying Quartet and the American String Quartet to name only a few. His works have been performed lately by the St. Louis Symphony, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Mannheim Nationaltheater Orchestra. Besides these commissions and performances, previous commissions have been received from the National Endowment for the Arts (1975, 1978, 1980 and 1982), the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, the Koussevitzky Foundation, the City of Jerusalem, the Welsh Arts Council and many others. Adler has been awarded many

prizes including a 1990 award from the

American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Charles Ives Award, the

Lillian Fairchild Award, the MTNA Award for Composer of the Year

(1988-1989), and a Special Citation by the American Foundation of Music

Clubs (2001). In 1983 he won the Deems Taylor Award for his book, The

Study of Orchestration.

In 1988-1989 he was designated “Phi Beta Kappa Scholar.” In 1989 he

received the Eastman School’s Eisenhard Award for Distinguished

Teaching. In 1991 he was honored being named the Composer of the Year

by the American Guild of Organists. Adler was awarded a Guggenheim

Fellowship (1975-1976); he has been a MacDowell Fellow for five years

and; during his second trip to Chile, he was elected to the Chilean

Academy of Fine Arts (1993) “for his outstanding contribution to the

world of music as a composer.” In 1999, he was elected to the Akademie

der Kuenste in Germany for distinguished service to music. While

serving in the United States Army (1950-1952), Adler founded and

conducted the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra and, because of the

Orchestra’s great psychological and musical impact on European culture,

was awarded a special Army citation for distinguished service. In May,

2003, he was presented with the Aaron Copland Award by ASCAP, for

Lifetime Achievement in Music (Composition and Teaching). Adler has appeared as conductor

with many major symphony orchestras, both in the U.S. and abroad.

His compositions are published by Theodore Presser Company, Oxford

University Press, G. Schirmer, Carl Fischer, E.C. Schirmer, Peters

Edition, Ludwig Music, Southern Music Publishers, Transcontinental

Music Publishers. Recordings of his works have been done on RCA,

Gasparo, Albany, CRI, Crystal and Vanguard.

|

This interview was recorded at Bruce Duffie’s studio in Chicago on January 21, 1991. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1993, and twice in 1998. Programs were also presented on WNUR in 2005 and 2010, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2006 and 2008. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.