A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

AJK: I don’t even note it down. I just make

a mental note of it. Sometimes I’ll write a little comment. I

don’t typically have musical material coming into my head. I have

images about what ideas I like and what colors I’d like to be in a piece,

and I’ll just put that in the back of my mind and go on with what I’m doing,

and then come back to it. If it keeps coming back to me, I know it’s

something that I should pursue.

AJK: I don’t even note it down. I just make

a mental note of it. Sometimes I’ll write a little comment. I

don’t typically have musical material coming into my head. I have

images about what ideas I like and what colors I’d like to be in a piece,

and I’ll just put that in the back of my mind and go on with what I’m doing,

and then come back to it. If it keeps coming back to me, I know it’s

something that I should pursue. AJK: I don’t have a position as a teacher, but

I do master classes here and there. Last year I taught at Bowdoin for

a week, and have done a number of different residency situations which I

find very gratifying. I like to be more in the role of a mentor for

a short period of time and get to know people in an intense way for a short

period of time. It’s very satisfying. And I feel I’m not quite

yet ready to have a full-time teaching position with the amount of work that

I have to do.

AJK: I don’t have a position as a teacher, but

I do master classes here and there. Last year I taught at Bowdoin for

a week, and have done a number of different residency situations which I

find very gratifying. I like to be more in the role of a mentor for

a short period of time and get to know people in an intense way for a short

period of time. It’s very satisfying. And I feel I’m not quite

yet ready to have a full-time teaching position with the amount of work that

I have to do. AJK: Well! Of course I hope that they’ll

put as much of themselves as they can with their energy and their enthusiasm,

but I do believe that first performances should, to the best of intentions,

reflect pretty carefully what’s in the score so that the composer can then

compare what works and what doesn’t. I’ve had some experiences, in the

last few years especially, where the first performances were very, very different

than what my intentions were. With one piece that was just revised

and re-premiered a few months ago, I had to wait about two or three years

to really hear it as I wanted to.

AJK: Well! Of course I hope that they’ll

put as much of themselves as they can with their energy and their enthusiasm,

but I do believe that first performances should, to the best of intentions,

reflect pretty carefully what’s in the score so that the composer can then

compare what works and what doesn’t. I’ve had some experiences, in the

last few years especially, where the first performances were very, very different

than what my intentions were. With one piece that was just revised

and re-premiered a few months ago, I had to wait about two or three years

to really hear it as I wanted to. AJK: Oh, I just

love it! It’s really my first love because I was a choral singer even

before I was a lousy violinist, so I don’t really consider that much of anything.

But my first pieces were choral songs, so I really brought that kind of love

of vocal music into my work, in general. There I’ve had pretty consistently

very, very good experiences.

AJK: Oh, I just

love it! It’s really my first love because I was a choral singer even

before I was a lousy violinist, so I don’t really consider that much of anything.

But my first pieces were choral songs, so I really brought that kind of love

of vocal music into my work, in general. There I’ve had pretty consistently

very, very good experiences. AJK: I’m optimistic about composition and quality

performance, definitely. I’m very confused about what the landscape

is going to look like. I don’t want to see orchestras going bankrupt.

Do we have too many of them? Are the administrative ends of the orchestras

out of balance — in size and in budget —

with the musicians? The musicians are definitely being paid

what they’re worth, but is that too much? Is it enough? Is it

the right amount?

AJK: I’m optimistic about composition and quality

performance, definitely. I’m very confused about what the landscape

is going to look like. I don’t want to see orchestras going bankrupt.

Do we have too many of them? Are the administrative ends of the orchestras

out of balance — in size and in budget —

with the musicians? The musicians are definitely being paid

what they’re worth, but is that too much? Is it enough? Is it

the right amount? In 1983, the New York Philharmonic premiered a work entitled Dream of

the Morning Sky that came from the pen of a 23-year-old composer named

Aaron Jay Kernis. It would result in his national acclaim, and his star would

only grow. He has won honors from ASCAP, BMI, the National Endowment for

the Arts, the Guggenheim Foundation, the New York Foundation for the Arts

and the American Academy in Rome; eventually he went on to be the youngest

composer ever to receive a Pulitzer Prize—awarded for his String Quartet

No. 2 (“musica instrumentalis”) in 1998. He won the prestigious Grawemeyer

Award in Music Composition in 2002 for his work Colored Field, making

him the youngest composer to win that prize as well. He would also go on to

be commissioned by Disney to ring in the new millennium with his choral symphony

Garden of Light. The list of people who have commissioned and

performed Kernis’ work runs a veritable who’s who of the classical music world,

and his list of honors and awards make him among the most feted composers.

He is one of America’s leading lights, having passed from youthful phenomenon

to a genuine potent and original artist, possessed of an accessible yet sophisticated

voice. “With each new work and new recording,” says the San Francisco Chronicle,

“Kernis solidifies his position as the most important traditional-minded composer

of his generation. Others may be exploring musical frontiers more restlessly,

but no one else is writing music quite this vivid or powerfully direct.”

In 1983, the New York Philharmonic premiered a work entitled Dream of

the Morning Sky that came from the pen of a 23-year-old composer named

Aaron Jay Kernis. It would result in his national acclaim, and his star would

only grow. He has won honors from ASCAP, BMI, the National Endowment for

the Arts, the Guggenheim Foundation, the New York Foundation for the Arts

and the American Academy in Rome; eventually he went on to be the youngest

composer ever to receive a Pulitzer Prize—awarded for his String Quartet

No. 2 (“musica instrumentalis”) in 1998. He won the prestigious Grawemeyer

Award in Music Composition in 2002 for his work Colored Field, making

him the youngest composer to win that prize as well. He would also go on to

be commissioned by Disney to ring in the new millennium with his choral symphony

Garden of Light. The list of people who have commissioned and

performed Kernis’ work runs a veritable who’s who of the classical music world,

and his list of honors and awards make him among the most feted composers.

He is one of America’s leading lights, having passed from youthful phenomenon

to a genuine potent and original artist, possessed of an accessible yet sophisticated

voice. “With each new work and new recording,” says the San Francisco Chronicle,

“Kernis solidifies his position as the most important traditional-minded composer

of his generation. Others may be exploring musical frontiers more restlessly,

but no one else is writing music quite this vivid or powerfully direct.”

In coming down on a particular side of the now-defunct schism between the avant-garde and the listening public, Kernis safely sides with neither—hewing, instead, to his own personal vision of what is beautiful, flowing easily from moments of dissonance to moments of lyrical resolution. Or, as one critic wrote: “Kernis is at or near the top of a list of young American composers who have made it safe for music lovers to return to the concert hall and enjoy new music that neither panders to nor alienates audiences.” With this as his raison d’etre, Kernis might well be among the true postmodernists. Born in Philadelphia in 1960, Kernis, largely self taught on violin, piano, and composition, attended the San Francisco Conservatory, the Manhattan School of Music, and Yale University, working along the way with a diverse array of teachers: John Adams, Charles Wuorinen, Morton Subotnick, Bernard Rands and Jacob Druckman. His West to East coast trajectory is betrayed in the wild catholic range of his influences—everything from Gertrude Stein to hard-edged rap to the diaphanous musical canvas of Claude Debussy. Coming up when he did, in the 1980s and 90s, he took from what was around him—the disparate musics and the collapsing aesthetic streams—and, gathering influence from his broad swathe of teachers, forged a rich, distinctive, emotionally immediate music, neither “this” nor “that” but simply and clearly good. The brilliance of his work rests on the exuberant splay of his instrumental palette (even when writing solo or chamber music) crossed with a brooding, poetic depth cut in sharp relief: wild, visceral, violent passages against calm, prayer-like quietude. “Kernis,” Michael Fleming wrote in the St. Paul Pioneer Press, wrote, “is a composer of fastidious technique and wide-ranging imagination.”  During the 1980s and 1990s, Kernis composed two deeply contrasting symphonies,

works that were to him were pre- and post-tragic—the tragedy, in this instance,

being the first Gulf War of 1991, an event that affected him deeply. Before

it struck, his 1989 Symphony in Waves (commissioned by the Saint Paul

Chamber Orchestra), a large-scale five-movement work, is of a particularly

colorful bent, caffeinated and lively, but with passages of overwhelming lyricism;

in contrast, his Symphony No. 2 (1991), commissioned by the New Jersey

Symphony, is an enraged, topical work, delineated by aggressive, clangorous

writing for percussion.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Kernis composed two deeply contrasting symphonies,

works that were to him were pre- and post-tragic—the tragedy, in this instance,

being the first Gulf War of 1991, an event that affected him deeply. Before

it struck, his 1989 Symphony in Waves (commissioned by the Saint Paul

Chamber Orchestra), a large-scale five-movement work, is of a particularly

colorful bent, caffeinated and lively, but with passages of overwhelming lyricism;

in contrast, his Symphony No. 2 (1991), commissioned by the New Jersey

Symphony, is an enraged, topical work, delineated by aggressive, clangorous

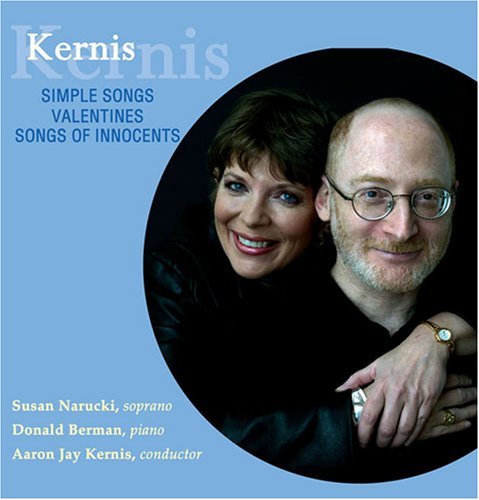

writing for percussion. Other orchestral pieces by this accomplished colorist include Newly Drawn Sky (2005); Color Wheel (2001); Musica Celestis (1990) for string orchestra; New Era Dance (1992), commissioned to mark the New York Philharmonic’s 150th anniversary, which Edward Seckerson called “…Aaron Jay Kernis' street-smart power-mix circa 1992. Latin salsa and crackmobile rap meets 1950s jazz;” a violin concerto, Lament and Prayer, written in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II and the Holocaust; Goblin Market (1995), a setting of Christina Rosetti’s puckish poem for narrator and large ensemble; and Air for violin and orchestra, commissioned in 1995 by Joshua Bell (originally for violin and piano, but later reconfigured for orchestra and premiered in 1996). His chamber, solo and vocal repertoire is equally colorful and varied: Two Movements (with Bells) (2007); the salsa-inspired 100 Greatest Dance Hits for guitar and string quartet from 1993; Quattro Stagioni dalla Cucina Futurisimo (“The Four Seasons of Futurist Cuisine”) for narrator, violin, cello and piano; and the piano quartet Still Movement with Hymn (1993), commissioned by American Public Radio for Chrisopher O’Riley, Pamela Frank, Paul Neubauer, and Carter Brey; a song cycle for soprano Renée Fleming, scored for voice and piano and later orchestrated and performed by the Minnesota Orchestra; and the piano suite Before Sleep and Dreams (1990) written for superstar pianist Antony De Mare. Kernis served for over ten years as new music advisor to the Minnesota Orchestra and he is currently the Director of Minnesota Orchestra’s Composers Institute. Each season, in partnership with the American Music Center, eight or so composers are given the chance to hear their music performed by a professional orchestra after a week-long immersion under the trained and experienced eye of the composer. — January 2009 [From

the Schirmer Website] |

This interview was recorded at Northwestern University in Evanston,

IL, on November 15, 2002. Portions (along with recordings) were used

on WNUR in 2003, 2008 and 2009. This transcription was made and posted

on this website in 2009. It has also been included in the

internet channel Classical Connect.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.