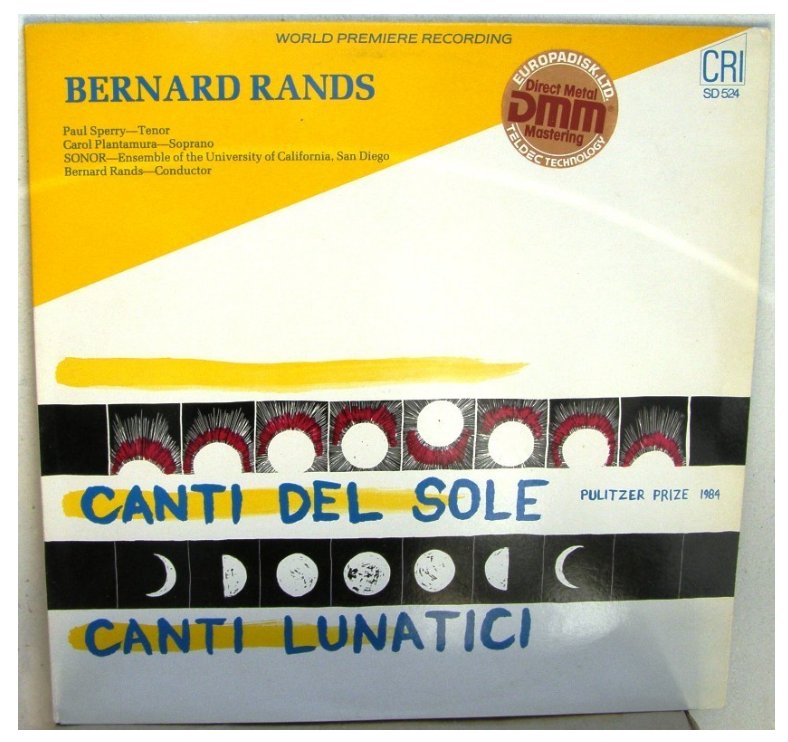

| Through more than a hundred published

works and many recordings, Bernard Rands is established as a major figure

in contemporary music. His work Canti del

Sole, premièred by Paul Sperry, Zubin Mehta and the New York

Philharmonic, won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize in Music. His large orchestral

suites Le Tambourin won the 1986

Kennedy Center Friedheim Award. Conductors including Barenboim, Boulez, Berio, Maderna, Marriner,

Mehta, Muti, Ozawa,

Rilling, Salonen, Sawallisch, Schiff, Schuller, Schwarz, Silverstein,

Sinopoli,

Slatkin, von Dohnanyi, and Zinman, among others,

have programmed his music. [Note:

Names which are links refer to interviews by Bruce Duffie elsewhere on this

website.] The originality and distinctive character of his music have been variously described as ‘plangent lyricism’ with a ‘dramatic intensity’ and a ‘musicality and clarity of idea allied to a sophisticated and elegant technical mastery’ - qualities developed from his studies with Dallapiccola and Berio. Rands served as Composer-in-Residence with the Philadelphia Orchestra for seven years, from 1989 to 1995 as part of the Meet The Composer Residency Program for the first three years, with 4 years continued funding by the Philadelphia Orchestra. Rands’ works are widely performed and frequently commercially recorded. His work, Canti d’Amor, recorded by Chanticleer, won a Grammy Award in 2000. Born in England, Rands emigrated to the United States in 1975 becoming an American citizen in 1983. He has been honored by the American Academy and Institute of the Arts and Letters; Broadcast Music, Inc.; the Guggenheim Foundation; the National Endowment for the Arts; Meet the Composer; the Barlow, Fromm and Koussevitsky Foundations, among many others. In 2004, Rands was inducted to the American Academy of Arts & Letters. Recent commissions have come from the Suntory concert hall in Tokyo; the New York Philharmonic; Carnegie Hall; the Boston Symphony Orchestra; the Cincinnati Symphony; the Los Angeles Philharmonic; the Philadelphia Orchestra; the B. B. C. Symphony Orchestra; the National Symphony Orchestra; the Internationale Bach Akademie; the Eastman Wind Ensemble and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Many chamber works have resulted from commissions from major ensembles and festivals from around the world. His chamber opera, Belladonna, was commissioned by the Aspen Festival for its fiftieth anniversary in 1999. A dedicated and passionate teacher, Rands has been guest composer at many international festivals and Composer-in-Residence at the Aspen and Tanglewood festivals and was Walter Bigelow Rosen Professor of Music at Harvard University. Recent works include "chains like the sea" commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and dedicated to Maestro Lorin Maazel, which was premiered in the Fall of 2008; Adieu, premiered by the Seattle Symphony in December, 2010 in honor of Gerard Schwarz's farewell season; and Three Pieces for Piano, which was premiered in December, 2010 by renowned pianist Jonathan Biss who took the piece on a subsequent tour through Europe and the US including the work's Carnegie Hall debut in January, 2011. His opera Vincent debuted to critical acclaim at Indiana University Opera Theatre in April of 2011, conducted by Arthur Fagen and directed by Vincent Liotta. Rands' latest orchestral work Danza Petrificada premiered with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in May of 2011, led by the composer's longtime friend and collaborator Maestro Riccardo Muti. |

|

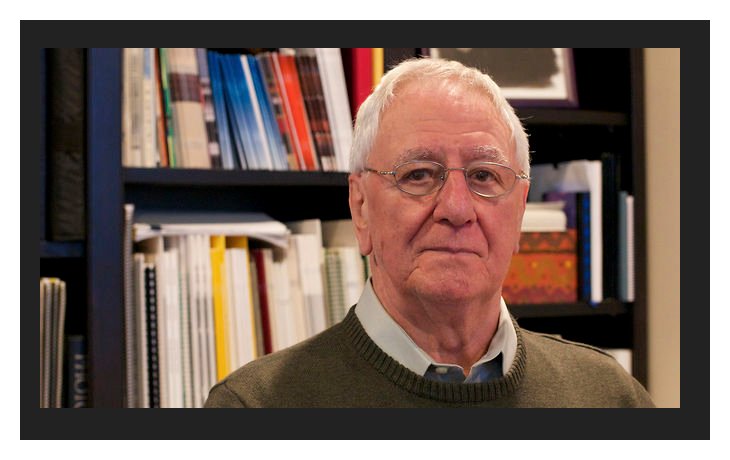

Bernard Rands in Chicago

The following works have been programmed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra over the years . . . 1. Le Tambourin - Suites 1 & 2 conducted by Pierre Boulez (1993 - at the time of this interview) 2. Prelude & Sans voix parmi les voix - (CSO commission) to celebrate the 70th birthday of Pierre Boulez 3. Apokryphos for Soprano solo, Chorus and Orchestra (CSO commission) conducted by Daniel Barenboim (2003) 4. 'Cello Concerto # 1 - Johannes Moser ('Cello) conducted by Pierre Boulez (2005) 5. Danza Petrificada (CSO commission) conducted by Riccardo Muti and featured on the orchestra's European tour in Paris, Luxembourg, Lucerne, Salzburg and Vienna (2011) 6. "...where the murmurs die..." (New York Phil. commission) conducted by Christoph Eschenbach (scheduled for December, 2013) The following are some of the other

works performed at various times in and around Chicago . . .

Concertino for Oboe and Ensemble - ICE Ensemble conducted by Cliff Colnot Concertino for Oboe and Ensemble - Univ. of Chicago New Music Ensemble conducted by Cliff Colnot Concertino for Oboe and Ensemble - Dal Niente Ensemble conducted by Michael Lewansky Concertino for Oboe and Ensemble - CSO Music Now conducted by Cliff Colnot "Now Again" - fragments from Sappho - Contempo conducted by Cliff Colnot "Now Again" - fragments from Sappho - De Paul New Music Ensemble conducted by Michael Lewansky String Quartet # 2 - Chicago Chamber Musicians String Quartet # 2 - Fifth House Ensemble Preludes for Piano Memo 4 for Solo Flute - several performances by Molly Barth Tre Canzoni Senza Parole - De Paul Orchestra conducted by Michael Lewansky Tableau - Eighth Blackbird Ensemble "...in the receding mist..." - ICE Ensemble conducted by Cliff Colnot Canti Lunatici for Soprano & Ensemble - Chicago Chamber Musicians |

BR: I have, over the years, had some very good

students, quite a number of whom have made and are making their way professionally.

They’re producing work of substance and quality, and are getting recognition

for it. So your question has to be answered in a very specific way.

If I generalize, then I would probably have a more negative answer in the

sense that many young people now are in music studies of one kind or another

in universities and institutions of all kinds. That is entirely valuable

as a civilizing influence, as an intellectual discipline, as a discovery for

themselves and of themselves, and hopefully bringing them to an appreciation

of an art form that is so fantastic and so wonderful and rewarding.

However, it’s also very demanding, as we’ve already said, about rigor and

preciseness, and I don’t very often see the kind of talent that I know immediately

can sustain itself. So there is an educational side which has its value,

and there is an enthusiasm and an ambition — not a vaulting

ambition, but a perfectly reasonable ambition that cannot be realized

— and that’s frustrating because one can see that it’s not going

to happen.

BR: I have, over the years, had some very good

students, quite a number of whom have made and are making their way professionally.

They’re producing work of substance and quality, and are getting recognition

for it. So your question has to be answered in a very specific way.

If I generalize, then I would probably have a more negative answer in the

sense that many young people now are in music studies of one kind or another

in universities and institutions of all kinds. That is entirely valuable

as a civilizing influence, as an intellectual discipline, as a discovery for

themselves and of themselves, and hopefully bringing them to an appreciation

of an art form that is so fantastic and so wonderful and rewarding.

However, it’s also very demanding, as we’ve already said, about rigor and

preciseness, and I don’t very often see the kind of talent that I know immediately

can sustain itself. So there is an educational side which has its value,

and there is an enthusiasm and an ambition — not a vaulting

ambition, but a perfectly reasonable ambition that cannot be realized

— and that’s frustrating because one can see that it’s not going

to happen. BR: In general terms, every composer is different

in how they understand what it is that they are grappling with and coping

with, and what they’re transcribing from their inner understanding to a series

of notations. I have a sense of the whole piece in my mind before I

begin to write it. I don’t necessarily understand all the details,

but I’d say very simply I do tend to know its scope. A little piano

piece of five minutes that occurs for whatever purpose or reason is obviously

going to be quite clear in one’s mind that it is that proportion, whereas

a large-scale work for orchestra and chorus with texts may be fifty minutes

or an hour. One knows those simple dimensions immediately, but I think

your question is a much more complicated one to answer, and much more complex

to know about. Without getting too technical, when one understands one’s

materials, knowing what their capacity is and having explored them and exploited

them in the best sense, one knows when they have reached their capacities.

They’ve been used and they’ve said what they have to say in that context.

Usually one knows that things are now in their right place, and that has

to do with reading the music over again. With every measure that’s

added and every page that’s added, one goes over it and over it and over

it from the beginning, performing it in one’s mind. If they’re something

of a lunatic that I am, I dance it, I sing it, I conduct it, I play it at

the piano. I do all kinds of things that gives me a sense of this is

right, this is the judgment that I’m making because formally, in all its

proportions and all its dimensions, it makes sense. It adds up because

of logic, because of conviction about it. Therefore, it is a moment

one knows. I remember seeing a very beautiful film about Jackson Pollock.

Here’s the actual painter working on a huge canvas, maybe the size of the

floor of this room, flicking paint. He is dipping in and flicking paint

here and there, changing colors sometimes with sticks not with brushes, and

the paint is flying all over the place. What makes him flick here now,

having flicked over there? It is because this computer in his head

is calculating all of the relationships and then painting. Then he’s

backing down to the far corner, and he eventually steps out and is finished

with that kind of utterly non-representational, totally abstract chance art.

I say “chance” guardedly.

There is the degree of ambiguity about the nature of it, in the sense that

when he makes the gesture he doesn’t quite know where the paint’s going to

go. So all of that is calculated all the time, being reviewed and reviewed

and reviewed until finally it’s there. When you look at a huge Jackson

Pollock on the wall at the Museum of Modern Art, you’re impressed by the

power of its statement. And he knew maybe one more splash would have

made something that drew attention away from everything else, or completely

distorted the proportions.

BR: In general terms, every composer is different

in how they understand what it is that they are grappling with and coping

with, and what they’re transcribing from their inner understanding to a series

of notations. I have a sense of the whole piece in my mind before I

begin to write it. I don’t necessarily understand all the details,

but I’d say very simply I do tend to know its scope. A little piano

piece of five minutes that occurs for whatever purpose or reason is obviously

going to be quite clear in one’s mind that it is that proportion, whereas

a large-scale work for orchestra and chorus with texts may be fifty minutes

or an hour. One knows those simple dimensions immediately, but I think

your question is a much more complicated one to answer, and much more complex

to know about. Without getting too technical, when one understands one’s

materials, knowing what their capacity is and having explored them and exploited

them in the best sense, one knows when they have reached their capacities.

They’ve been used and they’ve said what they have to say in that context.

Usually one knows that things are now in their right place, and that has

to do with reading the music over again. With every measure that’s

added and every page that’s added, one goes over it and over it and over

it from the beginning, performing it in one’s mind. If they’re something

of a lunatic that I am, I dance it, I sing it, I conduct it, I play it at

the piano. I do all kinds of things that gives me a sense of this is

right, this is the judgment that I’m making because formally, in all its

proportions and all its dimensions, it makes sense. It adds up because

of logic, because of conviction about it. Therefore, it is a moment

one knows. I remember seeing a very beautiful film about Jackson Pollock.

Here’s the actual painter working on a huge canvas, maybe the size of the

floor of this room, flicking paint. He is dipping in and flicking paint

here and there, changing colors sometimes with sticks not with brushes, and

the paint is flying all over the place. What makes him flick here now,

having flicked over there? It is because this computer in his head

is calculating all of the relationships and then painting. Then he’s

backing down to the far corner, and he eventually steps out and is finished

with that kind of utterly non-representational, totally abstract chance art.

I say “chance” guardedly.

There is the degree of ambiguity about the nature of it, in the sense that

when he makes the gesture he doesn’t quite know where the paint’s going to

go. So all of that is calculated all the time, being reviewed and reviewed

and reviewed until finally it’s there. When you look at a huge Jackson

Pollock on the wall at the Museum of Modern Art, you’re impressed by the

power of its statement. And he knew maybe one more splash would have

made something that drew attention away from everything else, or completely

distorted the proportions. BD: So there’s an innate musicality to that?

BD: So there’s an innate musicality to that? BR: No, except on special occasions. I’ve

heard Le Tambourin many, many times

and I’ve conducted it lots of times. But immediately when Shulamit Ran

told me that Pierre Boulez was doing it, even if I’d not been giving pre-concert

talks for all of this series, I would have wanted to be here anyway to see

him, be with him, spend time and talk because of what I said about him earlier

— that the consistency of his approach will be present, and there

will be a different understanding of it from others, and that’s fascinating.

But I’ve been very, very lucky. There are times, of course, when like

everyone else I’ve been very dissatisfied.

BR: No, except on special occasions. I’ve

heard Le Tambourin many, many times

and I’ve conducted it lots of times. But immediately when Shulamit Ran

told me that Pierre Boulez was doing it, even if I’d not been giving pre-concert

talks for all of this series, I would have wanted to be here anyway to see

him, be with him, spend time and talk because of what I said about him earlier

— that the consistency of his approach will be present, and there

will be a different understanding of it from others, and that’s fascinating.

But I’ve been very, very lucky. There are times, of course, when like

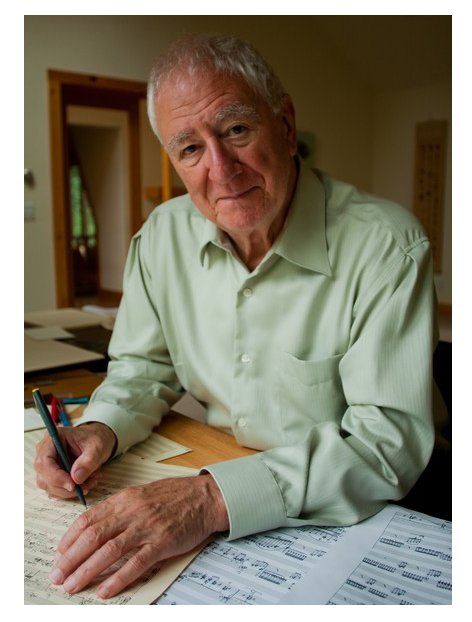

everyone else I’ve been very dissatisfied.This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on December 3,

1993. Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1994 and 1999,

and on WNUR in 2003. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the

Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription

was made and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.