A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: That’s my sport…swimming. I

vote for that. [Coming back to the subject at hand] Tell me

the secret of singing Mozart.

BD: That’s my sport…swimming. I

vote for that. [Coming back to the subject at hand] Tell me

the secret of singing Mozart. SJP: Yes, that’s right. I

think Kiri will

agree that the work in the room at the beginning is important.

Sitting at the piano, I’ve always found those little sessions when

you have to go through the arias and the ensembles and discuss

points of phrasing is marvelous. When you

come to Puccini or even Verdi, so much is written already in the score,

so provided the singer is well-prepared and the conductor knows his

job, you don’t have that amount of discussion. But with Mozart

you can discuss and say, “Try it this way, or what about shading this

or

making it a diminuendo,” and so on. All of these are technical

things which the audience on the receiving end only appreciate because

they hear how fine-tuned the whole thing is. That’s the

collaboration which Kiri and I have enjoyed for a long

time, and it’s absolutely necessary. It is also an ensemble

piece. For example, in the lovely

ensemble trios and quartets, and quintets or sextets of Figaro, it’s no use having

one voice which is going to stick out. In the ensemble pieces,

they’ve got to listen to each other and that’s great.

SJP: Yes, that’s right. I

think Kiri will

agree that the work in the room at the beginning is important.

Sitting at the piano, I’ve always found those little sessions when

you have to go through the arias and the ensembles and discuss

points of phrasing is marvelous. When you

come to Puccini or even Verdi, so much is written already in the score,

so provided the singer is well-prepared and the conductor knows his

job, you don’t have that amount of discussion. But with Mozart

you can discuss and say, “Try it this way, or what about shading this

or

making it a diminuendo,” and so on. All of these are technical

things which the audience on the receiving end only appreciate because

they hear how fine-tuned the whole thing is. That’s the

collaboration which Kiri and I have enjoyed for a long

time, and it’s absolutely necessary. It is also an ensemble

piece. For example, in the lovely

ensemble trios and quartets, and quintets or sextets of Figaro, it’s no use having

one voice which is going to stick out. In the ensemble pieces,

they’ve got to listen to each other and that’s great.  SJP: Part of it is the

size of the auditorium. My debut at the Metropolitan Opera was in

Così Fan Tutte, and I

was just underwhelmed by the difficult

acoustic. To be able to get the ensemble or the right kind of

sound at

Covent Garden is much easier. It has very good acoustic.

SJP: Part of it is the

size of the auditorium. My debut at the Metropolitan Opera was in

Così Fan Tutte, and I

was just underwhelmed by the difficult

acoustic. To be able to get the ensemble or the right kind of

sound at

Covent Garden is much easier. It has very good acoustic. SJP: There is perhaps more for the

conductor to think of the

style in French music. That arrives, for example, if you’re

playing a

Beethoven symphony and then you come to a Debussy tone poem or

something

like this. The texture of the writing is so different that you’re

not a

very good artist or conductor unless you take it into account, and

unless you ask the orchestra for this. It’s like the difference

between a water color or an oil painting. There’s a difference in

technique and there’s a

difference of effect on your eyes as you look. It is the

same with your ears when you hear the refinement like in this

beautiful Ravel song cycle that we’ve done together. This is such

tone painting and the poems. I live in France so I can be a bit

rude about the French, but I always say that they are so oriented

towards the spoken word. The French by and large

prefer dramatic theatre to opera or anything else. They are

taking big

strides now all over France to catch up. I don’t want to

offend anybody by saying that they need to catch up that much, but

their refinement is first and foremost directed towards spoken words or

plays in the theatre. When their language is sung to them, it

adds another dimension. For those who are not French-speaking,

the actual sound

comes first and they realize that it’s clothing the words in beautiful

sound. But every Frenchman that I know is really listening to

his mother tongue and then to the sound. Do you think that

is true?

SJP: There is perhaps more for the

conductor to think of the

style in French music. That arrives, for example, if you’re

playing a

Beethoven symphony and then you come to a Debussy tone poem or

something

like this. The texture of the writing is so different that you’re

not a

very good artist or conductor unless you take it into account, and

unless you ask the orchestra for this. It’s like the difference

between a water color or an oil painting. There’s a difference in

technique and there’s a

difference of effect on your eyes as you look. It is the

same with your ears when you hear the refinement like in this

beautiful Ravel song cycle that we’ve done together. This is such

tone painting and the poems. I live in France so I can be a bit

rude about the French, but I always say that they are so oriented

towards the spoken word. The French by and large

prefer dramatic theatre to opera or anything else. They are

taking big

strides now all over France to catch up. I don’t want to

offend anybody by saying that they need to catch up that much, but

their refinement is first and foremost directed towards spoken words or

plays in the theatre. When their language is sung to them, it

adds another dimension. For those who are not French-speaking,

the actual sound

comes first and they realize that it’s clothing the words in beautiful

sound. But every Frenchman that I know is really listening to

his mother tongue and then to the sound. Do you think that

is true? BD: Are we encouraging enough young

audiences to come to

theatre, opera, symphony, plays?

BD: Are we encouraging enough young

audiences to come to

theatre, opera, symphony, plays? KTK: It is very difficult now

because everyone knows that you get a more perfect sound and you get a

more

perfect recording than you do in the concert hall simply because

you can cut in a good note and take out a bad one. I really

don’t think that there is a great comparison. It’s not worlds

apart, but it is at least you can stop and have a drink

of water if you’re not having a great time. But in the theater

you have

to keep going.

KTK: It is very difficult now

because everyone knows that you get a more perfect sound and you get a

more

perfect recording than you do in the concert hall simply because

you can cut in a good note and take out a bad one. I really

don’t think that there is a great comparison. It’s not worlds

apart, but it is at least you can stop and have a drink

of water if you’re not having a great time. But in the theater

you have

to keep going.  KTK: That was seventeen years ago.

KTK: That was seventeen years ago. SJP: Kiri’s very

instinctive with music and always has

been, and if there is a little inaccuracy, she’s aware

of it. It’s rather like the princess with

the pea under the mattress. She can feel the discomfort about

something which has gone a

little bit wrong rhythmically or otherwise. It’s more that than

the pedantic. I often feel that listeners to music think that

we’re

all very pedantic and mechanical about trying to get everything

absolutely right. It’s like getting a total figure right when you

cast them out by hand, but it isn’t somehow like

that. Error in any field of art causes a kind of feeling of

unease. It’s imbalance when it isn’t right. Somehow

singers,

for example, compose their own little phrases. I’ve often

conducted and thought I must tell them about it because

they’re singing different shapes; the same melody but slightly

different. This can happen and it

can become a habit. Therefore, there’s no discomfort in

there because it’s a musical instinct taking over from the

actual mechanics of learning something. I think instinct’s very

important in music.

SJP: Kiri’s very

instinctive with music and always has

been, and if there is a little inaccuracy, she’s aware

of it. It’s rather like the princess with

the pea under the mattress. She can feel the discomfort about

something which has gone a

little bit wrong rhythmically or otherwise. It’s more that than

the pedantic. I often feel that listeners to music think that

we’re

all very pedantic and mechanical about trying to get everything

absolutely right. It’s like getting a total figure right when you

cast them out by hand, but it isn’t somehow like

that. Error in any field of art causes a kind of feeling of

unease. It’s imbalance when it isn’t right. Somehow

singers,

for example, compose their own little phrases. I’ve often

conducted and thought I must tell them about it because

they’re singing different shapes; the same melody but slightly

different. This can happen and it

can become a habit. Therefore, there’s no discomfort in

there because it’s a musical instinct taking over from the

actual mechanics of learning something. I think instinct’s very

important in music. |

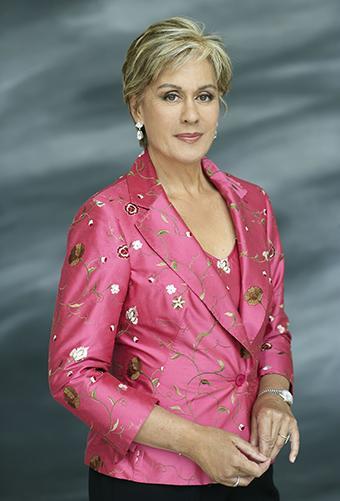

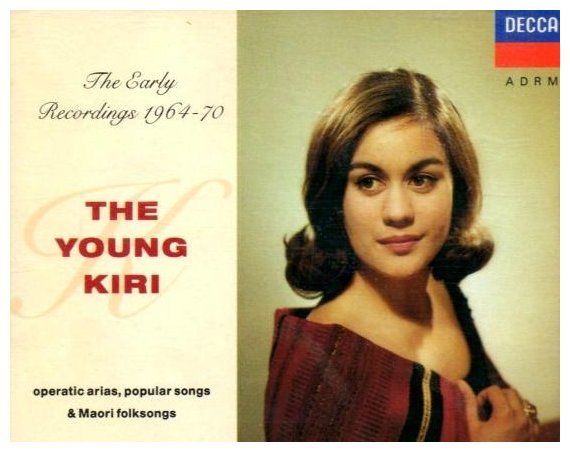

Kiri

Te Kanawa (Soprano)

Born: March 6, 1944 - Gisborne, on the east coast of New Zealand’s North Island The Maori soprano, Kiri Te Kanawa, is the adopted daughter of an Irish mother and Maori father. After winning the John Court Aria Prize and the Mobil Song Quest, Kiri shot to stardom in New Zealand and was accepted without audition to study at the London Opera Centre in 1965.  After appearing in little known operas such as Delibes’ Le Roi l’a dit and Wolf-Ferrari’s The Inquisitive Woman, Kiri Te Kanawa received critical praise as Idamantes in Mozart's Idomeneo. Soon after, Kiri was granted a three-year contract as a junior principal at Covent Garden. Kiri Te Kanawa came to international attention singing the role of Xenia in Boris Godunov and the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro. After achieving world-wide celebrity status, Kiri was made an Officer of the Civil Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, an honor that was later sold at a police auction for £500 to raise money for the Mitchum Amateur Boxing Association. After her successes at Covent Garden, Kiri Te Kanawa performed her Metropolitan Opera debut as Desdemona in Otello (replacing an ill Theresa Stratas). Her other performances include Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte, Arabella in Arabella, Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Violetta in La Traviata, Tosca in Tosca, Pamina in Die Zauberflöte and, most notably, her numerous performances as Donna Elvira in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. In 1981, Kiri Te Kanawa was chosen to sing "Let the Bright Seraphim" at St. Paul's cathedral at the marriage of HRH the Prince of Wales [shown in photo below] to the Lady Diana Spencer. The following year she was created a Dame of the British Empire by HM Queen Elizabeth II.  Kiri Te Kanawa married Desmond Park, whom she met on a blind date, in Auckland the 30th of August 1967. The couple adopted two children, Antonia and Thomas, in 1976 and 1979 respectively. The pair divorced in early 1997. Most recently, on March 10, 1994, Kiri performed in concert celebrating her 50th birthday at The Royal Albert Hall. |

|

Sir

John Pritchard, Music Director, Is Dead at 68

John Rockwell The New York Times December 6, 1989 Sir John Pritchard, the music director of the San Francisco Opera and, until early this year, of the BBC Symphony and the Cologne Opera, died of lung cancer yesterday at the Seton Medical Center in Daly City, Calif. He was 68 years old. An expert in the music of Mozart and Rossini as well as of contemporary composers, Sir John made his last public appearances in October in six performances of Mozart's ''Idomeneo'' in San Francisco. He was to have conducted Handel's ''Orlando Furioso'' there starting Nov. 19, but was unable to do so. John Michael Pritchard was born in London in 1921. He was taught music by his father, a violinist in the London Symphony Orchestra, and later studied viola and piano in Italy and conducting with Sir Henry Wood. In 1947 he joined the staff of the Glyndebourne Festival, becoming an assistant to Fritz Busch, and stepped in during a 1949 performance of Mozart's ''Don Giovanni'' when Busch fell ill. He made his formal conducting debut there in 1951, and his longtime association with the festival continued as a conductor, adviser and music director (1969-78). He is to be buried near the site of the festival. In an interview, he once recalled Busch telling him: ''John, you have a natural sense of tempo. You were born with it. It's the most priceless gift for conductors.'' Lifelong Freelancer Sir John's career was divided between concerts and opera. He made his debut with the Vienna State Opera and with the Royal Opera, Covent Garden, in 1952 and his American debut with the Pittsburgh Symphony in 1953. Although he freelanced throughout his life, his permanent engagements included music director of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (1957-63), the London Philharmonic (1962-66), the Theatre de la Monnaie in Brussels (1981-86), the Cologne Opera (1978 until this summer) and the BBC Symphony (1982 until October). In Liverpool, he was active in the Musica Viva concerts, subsequently repeated in London. He was knighted in 1983 for his service to English contemporary music. Among his important operatic premieres were Britten's ''Gloriana'' and Sir Michael Tippett's ''Midsummer Marriage'' and ''King Priam.'' In September he realized a longtime ambition by leading the final night of the Proms, the BBC's popular summer concert series at the Royal Albert Hall in London, although illness forced him to sit while conducting. Sir John's longtime companion was Terrence MacInnes. No family members survive. The funeral is to be in London late next week. The San Francisco Opera is to hold a memorial service on Monday at 11 A.M. at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco. |

This interview was recorded in her apartment in Chicago on

December 19, 1987. It was used as part of the

in-flight entertainment package aboard United Airlines and Air Force

One in 1988, and several times on WNIB. The

transcription was posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.