Soprano LEONTINA VADUVA

By Bruce Duffie

Like many Romanians from all walks of life, soprano Leontina Vaduva [pronounced VAH-doo-vah] has left her native country and made a home for herself and her family in the West. Singing French and Italian roles, Vaduva pleases critics and charms audiences wherever she goes. In 1988, she won the Laurence Olivier Award for 'Outstanding Achievement in Opera' for her portrayal of Manon at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden.

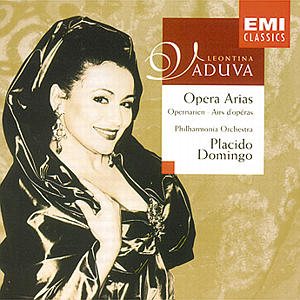

Her growing discography of complete roles includes Mimì in La Bohème on EMI, Antonia in Les Contes d'Hoffmann on Erato, and Gilda in Rigoletto on Teldec with fellow-Romanian Alexandru Agache [see his interview in The Opera Journal of December, 2001], plus an opera recital conducted by Plácido Domingo. Videos include Juliette in the Gounod opera with Roberto Alagna, and Micaela in Carmen, conducted by Zubin Mehta, both from Covent Garden. [See my interviews with Zubin Mehta.]

In the 2001-2002 season, Leontina Vaduva made her debut at

Lyric

Opera of Chicago in her signature role of Mimì. I arranged

to meet her in the office suite of the company between

performances.

During our chat, Ms. Vaduva mostly spoke French, and her husband

provided

the translation. Here is much of what we talked about in January

. . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Thank you very much for coming to Chicago. You're here for La Bohème and that seems to be a favorite role for you. Do you enjoy singing Mimì a lot?

Leontina Vaduva: I've been asked to sing her many times, but it gives me chills to do the role. I love performing it but I also would like to expand my repertoire and not just be known to be Mimì.

BD: Is it up to you or the producer to find something new in the role each time?

LV: With each role, I learn and find and discover a new accent in phrasing, a new accent in representation. It also depends on the maestro and his direction to find what it can bring.

BD: Do you bring some of yourself to this role, and every role?

LV: We enrich the roles we perform with our own experiences of life, so I do bring a little bit to each role I play.

BD: Does each role then enrich you as well?

LV: Each feminine role that I perform, from Manon and Antonia, Gilda, Norina, Susanna, to Blanche in Dialogues de Carmelites and Violetta enriches me with their spirit and their thinking.

BD: Is there any role that is a little too close to

the real

you?

LV: I think I have something from every one. Of all the roles, Mimì is the closest.

BD: You're not ill, are you???

LV: (Laughing) No, but I was when I was a child. Medicine makes many miracles. My personality is one of reserved modesty. I love beautiful things. I love friends and family and those souvenirs with them. That's why I feel Mimì touches very close to me.

BD: When you walk out on the stage, do you portray the character or do you become the character?

LV: I try to become the character. For example, as Norina in Don Pasquale, it's not my nature to be vindictive and use force with men, but I must overcome my nature and become the person of Norina onstage.

BD: Is it good to get these feelings out so they don't intrude on your personal life?

LV: Absolutely.

BD: Performing becomes a psychological exercise for you?

LV: Exactly! For an artist, for a producer or director, the theater offers psychoanalysis that's very, very deep.

* * * * *

BD: Your voice imposes certain roles. Do you enjoy those characters?

LV: Yes, very much. For example, I love to sing Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro because my nature is alive and full of life.

BD: And speaking of alive, you wind up alive at the end!

LV:

Not many roles allow me not to be dead at the end.

LV:

Not many roles allow me not to be dead at the end.

BD: Do you like dying onstage?

LV: It's a very hard experience and exercise. At least I can come back to life after each performance. We know we can come back. (Laughter all around)

BD: Does that influence your choice of roles perhaps - to find a couple more where you do survive to the final curtain?

LV: No. It's not being alive or dead at the end. It's the whole opera, the whole role that influences my decision whether to take it or not. And also, of course, if it fits my voice.

BD: How do you know, before you have sung the role, if it fits your voice?

LV: I went to the conservatory and I've worked many hours there and had many professors that have advised me. And the theaters probably know whether it's a good role for me before they propose it.

BD: You feel they hear it in your voice?

LV: Yes. At the beginning of my career I was a very light, lyric-legère. The voice developed toward the lyric-dramatic and so I started doing Bohème and Marguerite in Faust, and Simon Boccanegra.

BD: Is the voice continuing to get darker and heavier?

LV: It's not a question of getting heavier or darker. Drama doesn't signify the tone of the voice. It's more the capacity of giving the dramatic accents.

BD: You trust the ideas that the theaters and your teachers give you?

LV: Yes, and my experience up to this moment. I can sing Nedda in Pagliacci with no problem, or, in the next two to three years, Butterfly If the music is very dramatic, we should not forget that the character is 15 years old and we need to give a little bit of freshness and life to the voice.

* * * * *

BD: In opera, how much is music and how much is drama?

LV: Equal parts. Opera signifies also the text. It's a theater piece that's based on music.

BD: Another balance question - how much is art and how much is entertainment?

LV: I think that the performer should always think of opera as art. The public, perhaps, goes to the theater to be entertained and we have to work very hard to show the spirit onstage through what is seen and what is heard.

BD: Are you responsible for delivering a performance for each and every person in the audience each night?

LV: The journalists in the audience may be having a bad day and they can't feel the joy that I'm trying to give each individual... including themselves!

BD: Do you read the critics?

LV: Yes. I'm very conscious that the critic in the audience is not representative of the whole theater. They are not a mirror of the audience. It's a personal view, but by the experience of the critics I can try to take what I can and make it better.

BD:

Do you always strive to get better?

BD:

Do you always strive to get better?

LV: Yes. I will try to do better all the way to the end of my career.

BD: Can you ever get it ‘right?'

LV: It's an abstract perfection.

BD: So there are different kinds of perfection?

LV: Yes, perfection can be different.

BD: Does it warm your heart when you achieve a special night?

LV: Yes. We must always understand that there exists a difference between what I feel inside of me and what comes out, and what the public feels outside of me. I can feel inside that I've given a magnificent phrase, but the public may not understand or feel it. It's possible. It depends on the magnetic contact between the two - the public and the artist.

BD: You try to establish that contact?

LV: Yes, very much.

BD: The singer and the public... and the composer?

LV: The music is there. The music exists and each one has to learn and read what is written by the composer. Our liberty exists in the interpretation and that's why it's there. The music exists to be interpreted. All of modern art is based on the interpretation of the public today.

BD: Speaking of modern art, do you sing any recent operas, or even any world premieres?

LV: No, not yet. I've not had the opportunity.

BD: What advice would you have for a composer who wanted to write for your voice?

LV: I would say of course, if the music and the story were right for both the composer and for me.

* * * * *

BD: Do you also sing concerts as well as opera?

LV: I sing many recitals, but my career is now much more opera. I sing about four or five recitals each year.

BD: Is there a more intimate contact with the audience when you're doing a recital?

LV:

It's completely different. With an opera, there's a character in

costume in a production, and there's the story. With a recital,

each

song is a different interpretation, a different personality, and it's

difficult.

A recital demands more attention.

LV:

It's completely different. With an opera, there's a character in

costume in a production, and there's the story. With a recital,

each

song is a different interpretation, a different personality, and it's

difficult.

A recital demands more attention.

BD: Does it drive you crazy to go from character to character to character to character?

LV: No, I like it very much. It's a wonderful exercise and I like it very much.

BD: When designing a recital program, do you, perhaps, find similar characters to group together?

LV: I don't force a theme on a program. I love to have a diverse program. For example, in the French repertoire there's a Romanian composer Georges Enescu and he set texts by Clément Marot, the French poet. It's very different. Each song has a different character. Every one is a cycle.

BD: Is Enescu a bit closer to your heart because you are both from Romania?

LV: Yes.

BD: How long were you in Romania before you left?

LV: I left in 1988 for France. At the end of the international competition in 1985, I won many prizes and was invited by France to sing Manon at the Capitole of Toulouse. Then, I went to the Opéra in Paris and Covent Garden, and at that time it became a problem to travel because of the communist government, so when I finally arrived in France, I decided to stay.

BD: Did the music help to keep you alive when you were working under the communists?

LV:

During that time it was very hard to do any art. The conditions

did

not exist, economically speaking. As a student, I remember

singing

in a theater where it was minus four degrees and the orchestra was

playing

with gloves. The public in the theater were dressed as if they

were

outside. This signifies that art is very important to keep up the

morale of individuals. It was through art, especially music, that

we were able to go through this very difficult period.

LV:

During that time it was very hard to do any art. The conditions

did

not exist, economically speaking. As a student, I remember

singing

in a theater where it was minus four degrees and the orchestra was

playing

with gloves. The public in the theater were dressed as if they

were

outside. This signifies that art is very important to keep up the

morale of individuals. It was through art, especially music, that

we were able to go through this very difficult period.

BD: Do we in the West, who have life a little easier, forget that?

LV: No, I don't know. Maybe the only time you see this is during wartime. With the conveniences of life in the West we can't forget the difficulties of life and take it for granted. For somebody that comes from the East, we think more of the people that were close to us in the East. We appreciate very much the life in the West for being able to eat well and dress well and to be able to have the condition of a nice living and liberty. It's a shame that it's always in horrible moments in history that we find in our heart that we are all the same, just as on September 11 where we were all Americans. We need to find that place in the heart where it stays with us forever.

* * * * *

BD: Is opera for everyone?

LV: Yes. I love to listen to all kinds of music, so why can't others listen to opera?

BD: Is it special for you to sing French opera in France?

LV: It's very flattering for me, especially coming from Romania. But it's also flattering that this country and the people that live there have adopted me as French, and as one who sings French repertoire. I see many American artists sing this repertoire very well. What is particular about the French music is that you must treat is as almost Mozart. Generally, there is too much freedom in the phrasing. It is too sweet. The French music plays much with colors, between shadow and light. This transparency of light can become very heavy if we string out the phrasing. If we do the music precisely, we can hear all the different colors.

BD: Is there a secret to singing Mozart?

LV: I don't think so. Just follow the music! You must be very precise. You must not forget that Mozart utilized the Italian text because he admired the ‘music' of the Italian language. Sometimes we do the Mozart a bit more baroque. My taste is to have voices a little warmer.

BD: Is that because we've gotten used to the romantic style or because Mozart should be done that way?

LV: We need to ask Mozart to join us so we can ask what he wanted! (Laughter) It's hard to say. That's why I said it's the interpretation of each individual.

BD: Do you feel Wolfgang is happy with the way you do his music?

LV:

I hope so.

LV:

I hope so.

BD: Would you want him in the audience, or at rehearsal?

LV: I would love it very much because he was so alive and he loved life!

BD: Do you find that most composers are alive and love life?

LV: Yes. You can feel it in the music.

BD: Even in the death scenes?

LV: Yes.

BD: There is a living in the death?

LV: Yes, and afterwards as well. I, myself, do need time after the final curtain to resuscitate. But when I do Violetta, I think that her spirit was there when I was singing, and I was singing for that spirit and to that spirit.

BD: How much time do you need to return to yourself after the performance is over?

LV: At the beginning it was longer, especially when I do a role for the first time. After a couple hours, I can begin to relax, but the adrenaline continues to pump in even then.

BD: You are often killed... are there any roles you do where you kill someone else?

LV: No. I don't think I'll ever do Tosca. I look at her character, and she is very strong and it demands a little bit more darkness in the voice than my other roles.

BD: Is it right that in this new millennium you still portray victims?

LV: In general, in all of opera, we're all victims! (Laughter) Not just in opera, but in life we become victims to one thing or another. Just look in the history books. It existed yesterday and exists today. If Violetta or Mimì died of their diseases a century ago, today we find people dying of those (or other) diseases.

BD: Are you glad that you are living today rather than when these characters lived?

LV: I would love to have the experience to see how to live at the time of those characters, but I don't know if a time-machine to go to the future or the past is possible. But it would be interesting to have the experience.

BD: Is opera, perhaps, a temporary time-machine?

LV: Exactly.

* * * * *

BD: Do you enjoy making recordings?

LV:

Yes and no. I prefer the stage. If there is a recording of

the live performance, I prefer that. We have the audience and we

sing to the audience. It's not just for a good sound. I'm

not

adapted to the technical perfection. The technique must give more

of a relation to the character and the music. I don't like

perfection

without emotion. I prefer a voice that's imperfect but that gives

a very strong emotion. Even Callas was not 100% perfect, but what

she gave onstage was 1,000 times more interesting. She

constructed

a character and she lived each word.

LV:

Yes and no. I prefer the stage. If there is a recording of

the live performance, I prefer that. We have the audience and we

sing to the audience. It's not just for a good sound. I'm

not

adapted to the technical perfection. The technique must give more

of a relation to the character and the music. I don't like

perfection

without emotion. I prefer a voice that's imperfect but that gives

a very strong emotion. Even Callas was not 100% perfect, but what

she gave onstage was 1,000 times more interesting. She

constructed

a character and she lived each word.

BD: And you strive for this?

LV: Yes.

BD: Are you pleased with where you are at this point in your career?

LV: Yes. I think I'm in good voice and I'm trying to keep it.

BD: Is singing fun?

LV: Sometimes it's fun. Sometimes it's suffering. Depends on our own feeling at the moment.

BD: In the end is it all worth it?

LV: Always. I live for the stage.

- - - - - - -

= = =

- - - - - - -

Bruce Duffie has been contributing interviews to The

Opera Journal

on a regular basis since 1985. To see a list of those which have

been published, click HERE

. To see those which have been posted on this website,

click HERE

. In the next issue, a chat with baritone Rodney

Gilfrey.

= = = =

=

= = = =

- - - - - - - -

-

= = = =

=

= = = =

©2002 Bruce Duffie

FIrst published in The Opera Journal in September, 2002

Visit Bruce Duffie's Personal

Website and send him E-Mail

.