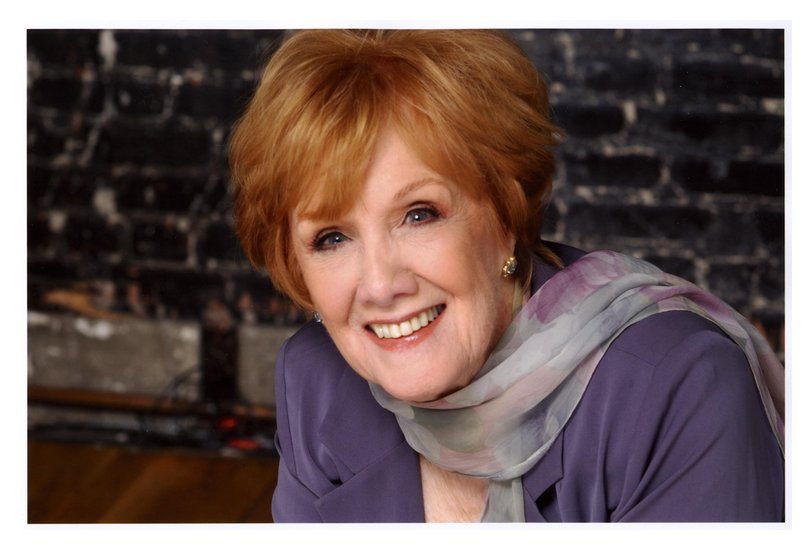

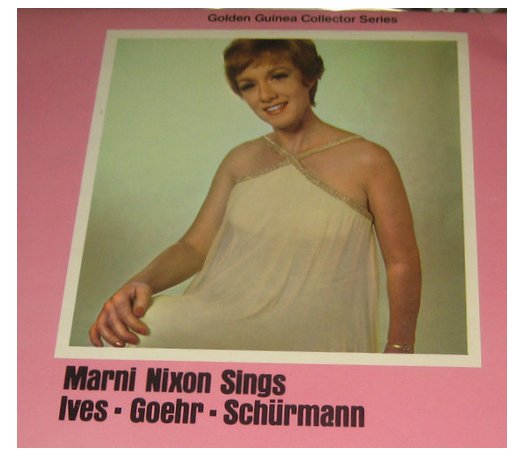

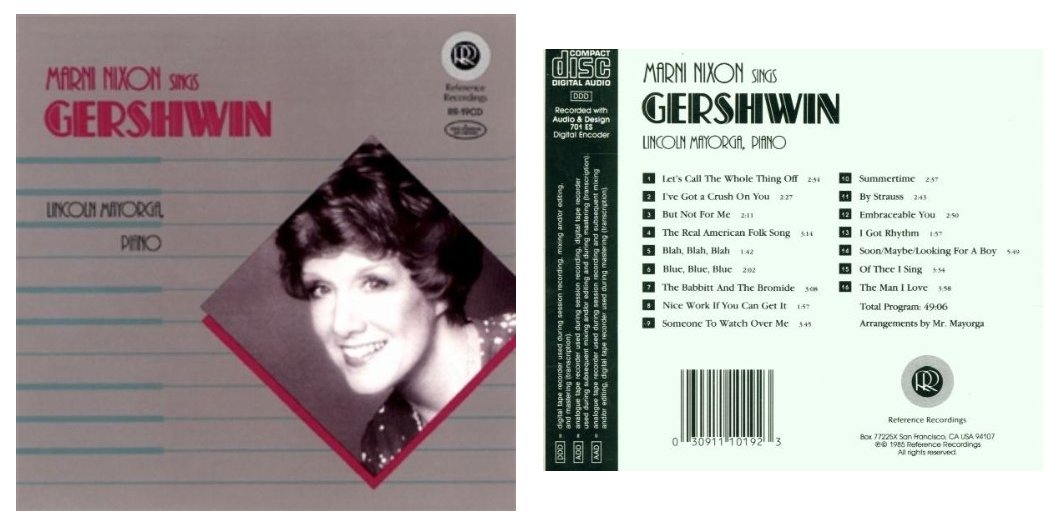

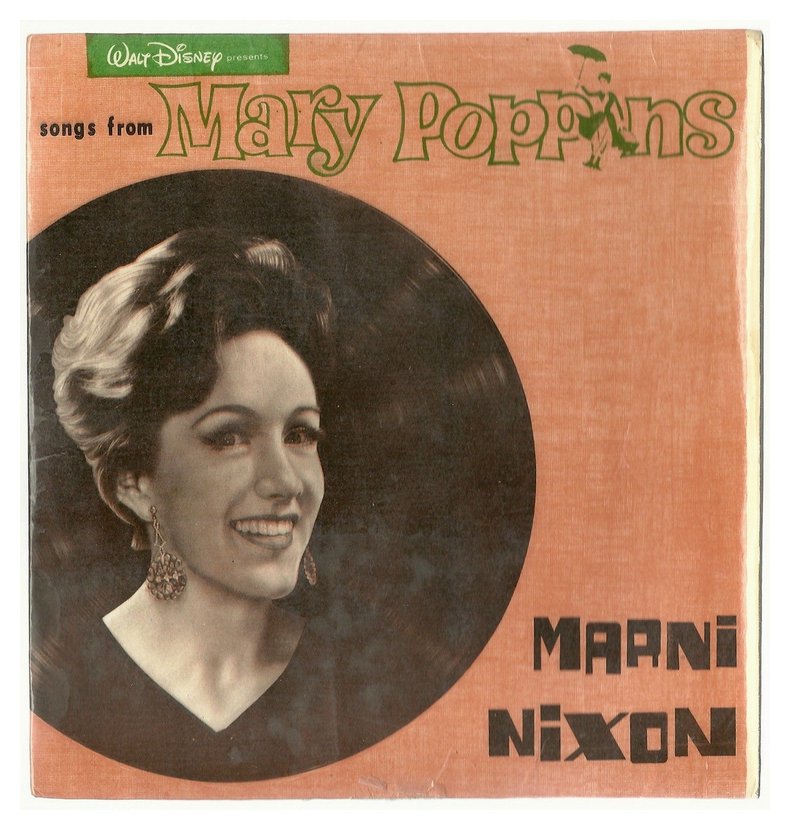

| "Loverly" soprano Marni

Nixon has ensured herself a proper place in film history although most

moviegoers would not recognize her if they passed her on the street.

But if you heard her, that might be a horse of a different color. Marni

is one of those unsung heroes (or should I say "much sung" heroes)

whose incredible talents were given short shrift at the time. For those

who think film superstars such as Deborah Kerr, Natalie Wood, and

Audrey Hepburn possessed not only powerhouse dramatic talents but

amazing singing voices as well...think again. Kerr's Anna in The King and I (1956), Natalie's

Maria in West Side Story

(1961), and Audrey's Eliza in My

Fair Lady (1964) were all dubbed by the amazing Marni Nixon, and

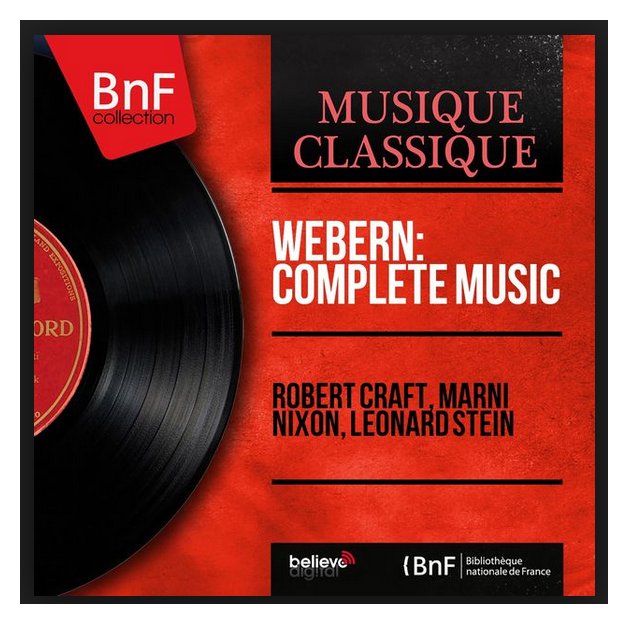

nowhere in the credits will you find that fact. Born Marni McEathron in Altadena, California, she was a former child actress and soloist with the Roger Wagner Chorale in the beginning. Trained in opera, yet possessing a versatile voice for pop music and easy standards as well, she not only sang for Arnold Schönberg and Igor Stravinsky but also recorded light songs. Marni made her Broadway musical debut in 1954 in a show that lasted two months but nothing came from it. In 1955, the singer contracted to dub Deborah Kerr in The King and I (1956) was killed in a car accident in Europe and a replacement was needed. Marni was hired...and the rest is history. Much impressed, the studios brought her in to "ghost" Ms. Kerr's voice once again in the classic tearjerker An Affair to Remember (1957). From there she went on to make Natalie Wood and Audrey Hepburn sound incredibly good with such classic songs as "Tonight" and "Wouldn't It Be Loverly." She finally appeared on screen in a musical in The Sound of Music (1965) starring Julie Andrews, who physically resembles Marni. The role is a small one, however, and she is only given a couple of solo lines in "How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria?" as a singing nun. Marni's vocal career in films dissolved by the mid 1960s, but she continued on with concerts and in symphony halls, while billing herself as "The Voice of Hollywood" in one-woman cabaret shows. Throughout the years, she has played on the legit stage, including the lead roles in The King and I and The Sound of Music, and in her matronly years has been seen as Fraulein Schneider in Cabaret, and in the musicals Follies and 70 Girls 70. Her last filmed singing voice was as the grandmother in the animated feature Mulan (1998) in the 1990s. Married three times, twice to musicians; one of her husbands, Ernest Gold, by whom she had three children, was a film composer and is best known for his Academy Award-winning epic Exodus (1960). - IMDb Mini Biography by Gary

Brumburgh

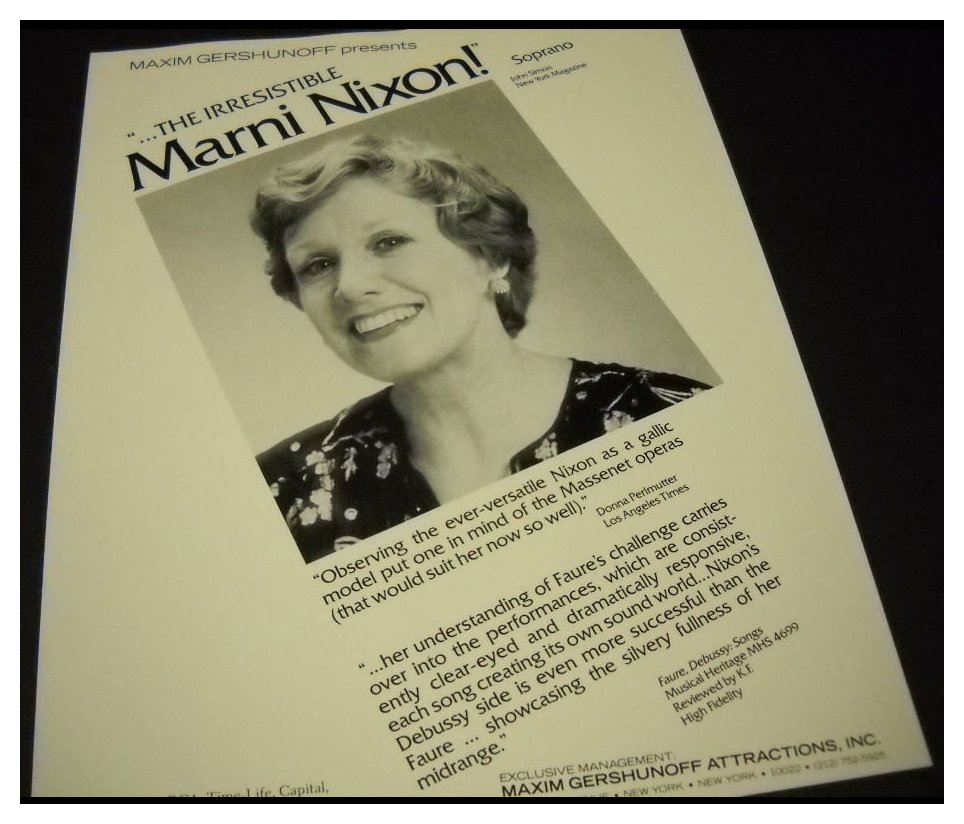

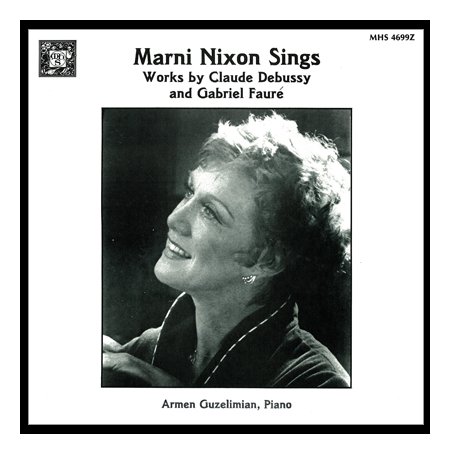

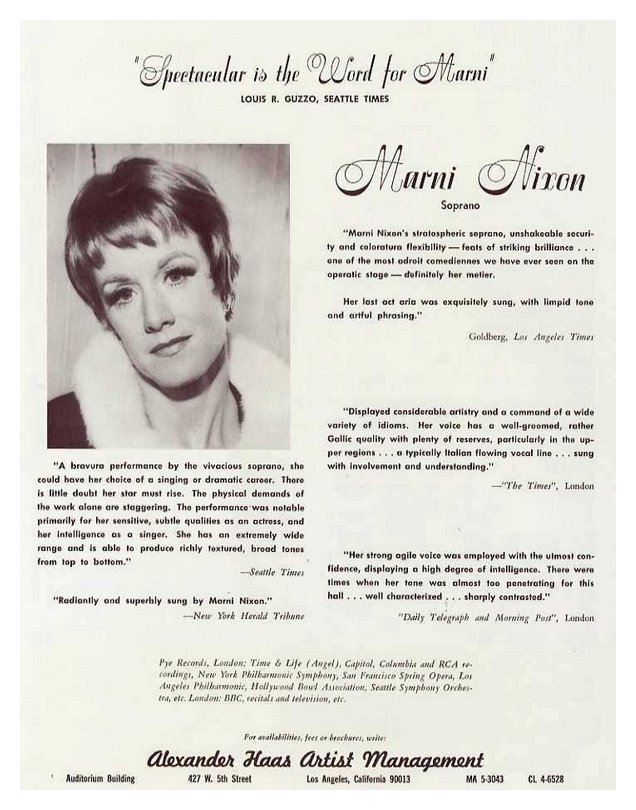

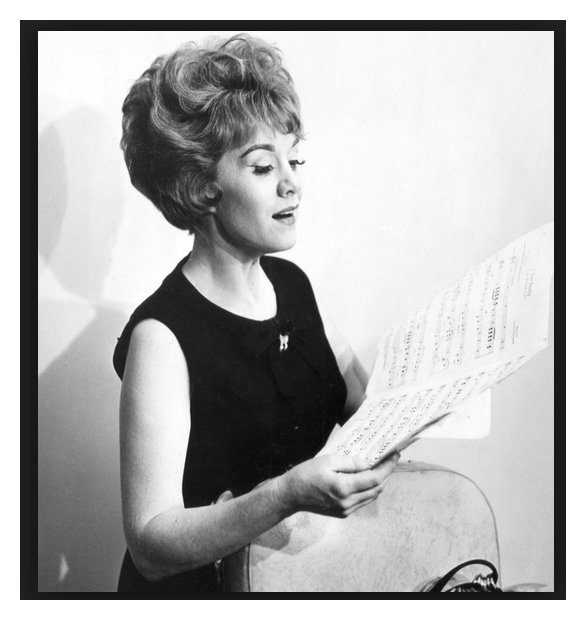

A few bits of

trivia about her, also from the Internet Movie Database, plus a booking

ad.

Started out at the age of four as a violinist and had a singing act with her sisters by age eight. Earned her reputation as "Singing Voice of the Stars" by "ghosting" other film luminaries as well, including Margaret O'Brien, Janet Leigh, and Jeanne Crain in some of their song sequences. She even touched up some singing parts for Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), dubbing the phrase "These rocks don't lose their shape" and some higher notes in the "Diamond's Are a Girl's Best Friend" number. She starred in her own local children's TV show in Seattle entitled Boomerang in the late 70s and early 80s and won four Emmys for her efforts. Toured extensively with both Liberace and Victor Borge.  |

MN: It’s like

defining

what’s gone wrong with Broadway. It’s such a complex

problem. First of all, just to dip into the

circle in some way, I don’t know what starts what or in what sequence

it happened, but there’s been an over-emphasis on huge operatic

voices. You have to make a career operatically to

exist economically as a singer, so the song in the meantime is what you

learn

before you really get where you want to get. This is the

impression people coming out of universities have, and the universities

have

taught them repertoire that was necessary to exist in the vocal realm

thirty years ago. The teachers only know that. The students

learn that very well, and faster and quicker than they used to.

They come out of the universities, and there’s nothing there.

Then they find that actors who can’t sing are getting the jobs.

Why? Because they

can communicate, and one forgets the fact that they can’t sing, or they

eventually learn how to sing besides, or they go into opera. The

opera world requires the singers to sing in these huge

auditoriums. They have to become amazons, and all the nuance goes

away. So the

satisfaction in singing a song — if you sing it

that way — goes down

the drain. It doesn’t hit the average person, and it doesn’t tell

a story anymore if you sing it too operatically. And yet these

huge

auditoriums make it necessary to produce these huge sounds, and you

have to spend so much of your energy and time just producing the sound

that you forget the meaning behind it, or it doesn’t come

through. So I think the concert organizations gradually were fed

by the agents who were pushing the operatic people, and would buy

people to do recitals that didn’t know really how to do recitals but

would sing a lot of operatic arias in a row, and said that was a

recital. Eventually the people who used to go to

recitals — maybe the European public who used to

love German Lieder and

French Mélodies, those

older people who were born in

Europe and came over here — are now dying away,

and their

generation is now being fed on instant gratification on

television. They don’t have all that knowledge of those kinds of

songs. They get fed so much of the opera that they never had the

lack of

any kind of entertainment. So they don’t seek the recital out as

some

necessary part of their cultural way of being, or to help their soul

hear these things. So gradually all of these things come to play,

and now everybody’s talking about it and writing about it, and the

singers are really able to identify that problem a little bit, and can

choose to say they don’t want to do opera. Their voice

isn’t big enough, so they’re going to do concerts, but there aren’t

any concerts, so they’re going to design a special program for their

church or

for their parents and their friends, and so you get to starting

again from scratch what the recital did in the very beginning.

That’s what I think is happening. It’s like a backlash

of this huge overblown sound.

MN: It’s like

defining

what’s gone wrong with Broadway. It’s such a complex

problem. First of all, just to dip into the

circle in some way, I don’t know what starts what or in what sequence

it happened, but there’s been an over-emphasis on huge operatic

voices. You have to make a career operatically to

exist economically as a singer, so the song in the meantime is what you

learn

before you really get where you want to get. This is the

impression people coming out of universities have, and the universities

have

taught them repertoire that was necessary to exist in the vocal realm

thirty years ago. The teachers only know that. The students

learn that very well, and faster and quicker than they used to.

They come out of the universities, and there’s nothing there.

Then they find that actors who can’t sing are getting the jobs.

Why? Because they

can communicate, and one forgets the fact that they can’t sing, or they

eventually learn how to sing besides, or they go into opera. The

opera world requires the singers to sing in these huge

auditoriums. They have to become amazons, and all the nuance goes

away. So the

satisfaction in singing a song — if you sing it

that way — goes down

the drain. It doesn’t hit the average person, and it doesn’t tell

a story anymore if you sing it too operatically. And yet these

huge

auditoriums make it necessary to produce these huge sounds, and you

have to spend so much of your energy and time just producing the sound

that you forget the meaning behind it, or it doesn’t come

through. So I think the concert organizations gradually were fed

by the agents who were pushing the operatic people, and would buy

people to do recitals that didn’t know really how to do recitals but

would sing a lot of operatic arias in a row, and said that was a

recital. Eventually the people who used to go to

recitals — maybe the European public who used to

love German Lieder and

French Mélodies, those

older people who were born in

Europe and came over here — are now dying away,

and their

generation is now being fed on instant gratification on

television. They don’t have all that knowledge of those kinds of

songs. They get fed so much of the opera that they never had the

lack of

any kind of entertainment. So they don’t seek the recital out as

some

necessary part of their cultural way of being, or to help their soul

hear these things. So gradually all of these things come to play,

and now everybody’s talking about it and writing about it, and the

singers are really able to identify that problem a little bit, and can

choose to say they don’t want to do opera. Their voice

isn’t big enough, so they’re going to do concerts, but there aren’t

any concerts, so they’re going to design a special program for their

church or

for their parents and their friends, and so you get to starting

again from scratch what the recital did in the very beginning.

That’s what I think is happening. It’s like a backlash

of this huge overblown sound. BD: Are the

colleges and universities perhaps turning

out too many people who want to be singers?

BD: Are the

colleges and universities perhaps turning

out too many people who want to be singers?

BD: When you’re

doing a live performance, do you ever

feel that you’re competing with your recorded material?

BD: When you’re

doing a live performance, do you ever

feel that you’re competing with your recorded material? MN: I enjoy recitals

the most because you can define

the material. It’s really your show, and you can

do it exactly for your voice. But there is something about the

operatic stage where you’ve got the dramatics for you. You’ve got

the costumes, you’ve got the hair, you’ve got the orchestra, you’ve got

the fellow performers. You can just plug yourself into it and

really get yourself into the role. You can really be complete

within that. I find that the most

glorious thing. I miss it a lot. I miss doing a lot

of oratorio singing, which I also like.

MN: I enjoy recitals

the most because you can define

the material. It’s really your show, and you can

do it exactly for your voice. But there is something about the

operatic stage where you’ve got the dramatics for you. You’ve got

the costumes, you’ve got the hair, you’ve got the orchestra, you’ve got

the fellow performers. You can just plug yourself into it and

really get yourself into the role. You can really be complete

within that. I find that the most

glorious thing. I miss it a lot. I miss doing a lot

of oratorio singing, which I also like.

BD: Do we expect

singers to be super-human?

BD: Do we expect

singers to be super-human? BD: Do the

composers writing today know how to write for the

voice?

BD: Do the

composers writing today know how to write for the

voice?© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 10, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, and again in 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.