BD

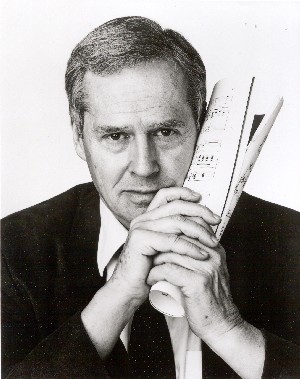

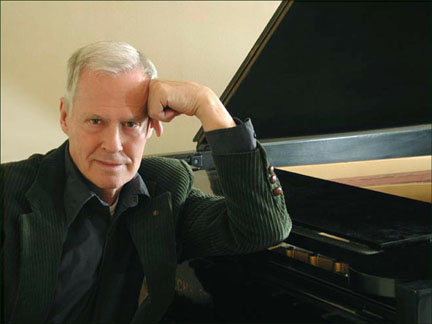

BD Composer Ned Rorem is one of the few visionaries who stuck to his guns (so

to speak) and wrote tonal music throughout the turbulent period of the second

half of the Twentieth Century. Besides all the sound ideas (pun intended),

he also penned volumes of prose observations about all aspects of his life

and surroundings. Originally diaries, this stream of thought poked and

prodded, enlightened and angered readers who may or may not have even heard

his music. Taken together, the output of this creator and observer

makes for a fascinating look at his imagination.

Composer Ned Rorem is one of the few visionaries who stuck to his guns (so

to speak) and wrote tonal music throughout the turbulent period of the second

half of the Twentieth Century. Besides all the sound ideas (pun intended),

he also penned volumes of prose observations about all aspects of his life

and surroundings. Originally diaries, this stream of thought poked and

prodded, enlightened and angered readers who may or may not have even heard

his music. Taken together, the output of this creator and observer

makes for a fascinating look at his imagination. BD: Is this what leads you to write some prose, because

it’s there and not a re-creative thing?

BD: Is this what leads you to write some prose, because

it’s there and not a re-creative thing?

NR: Yeah, let’s not waste our time talking about

the difference between contemporary classical and contemporary pop, even though

John Rockwell would love to do so. Of serious, so-called contemporary

classical — and all three of those terms are incorrect

— the average, or rather cultured American doesn’t know what the hell we’re

talking about when we talk about music. When you’re talking about song,

if they’re smart they think you’re talking about Stephen Sondheim, and if

they’re less cultured they think you’re talking about Bruce Springsteen,

but certainly not me, let alone any of my friends who write songs.

Nor are they thinking about opera composers who are writing operas today,

because opera composers are, by definition, dead, and have been dead for

a hundred years or so.

NR: Yeah, let’s not waste our time talking about

the difference between contemporary classical and contemporary pop, even though

John Rockwell would love to do so. Of serious, so-called contemporary

classical — and all three of those terms are incorrect

— the average, or rather cultured American doesn’t know what the hell we’re

talking about when we talk about music. When you’re talking about song,

if they’re smart they think you’re talking about Stephen Sondheim, and if

they’re less cultured they think you’re talking about Bruce Springsteen,

but certainly not me, let alone any of my friends who write songs.

Nor are they thinking about opera composers who are writing operas today,

because opera composers are, by definition, dead, and have been dead for

a hundred years or so. NR: All teaching is hype, so I do it partly for

the money. Three-fourths for the money, and one fourth because

I’m fairly good at the mysterious process of what it is. You can really

teach anything in the world in the performing arts except the making of it,

because I can make anybody, any beginner, into a fairly decent pianist with

a little bit of technique. They might not play with what used to be

called ‘feeling,’ but they can get the right notes. But with composing

you can’t start from scratch. You have to take the person who is presented

as a composer and he has to have written something so you can tell him what’s

wrong with it. You’d be amazed at the number of famous performers

— a Horowitz or a Rubenstein or a Joan Sutherland,

who deal with music all their life — who, if you said

to them, “Write me a piece for tomorrow,” would become panic stricken.

They don’t know even how to begin writing a piece. Partly that has

to do with basic education, because we all know how to read and write, and

paint pictures in nursery school. We write poems, we rhyme cat with

rat; we paint pictures, make mud pies. They might be lousy mud pies

and lousy poems, but at least we do them. But the basics of musical

education — what does a note mean on paper, on a staff

— is not taught to beginners. If it were, music would be

less mysterious. Although, I must hasten to add, it is still mysterious

to me. I still don’t know what it means, and I still don’t know what

in it can move me or anybody else to tears. Nobody knows — nobody

— and I’m not a fool, and neither is Susan Langer, who spent her

life writing on the philosophy of music. I do know, though, what in

music will move me in a very cold, medicinal way. I can be extremely

moved by a major seventh, or secondary seventh chords, and by sequences in

Bach and in Ravel. I can be left utterly cold by dominant sevenths.

Speaking in terms strictly of harmony, what moves me is the acrid sharpness

of a minor second or a major seventh, or minor ninth that then resolves.

The resolution to me is heartbreaking. I hear a lot of Bach, which

has a great deal of that kind of resolution, exactly as I hear Ravel or Poulenc,

which also has those chords, and yet Bach never knew who Poulenc and Ravel

were. I hear the music very similarly. I’ve talked to Rosalind

Turek, for example, who plays more Bach keyboard music than anybody else,

and she doesn’t know what I’m talking about because she doesn’t know the

contemporary allusions that I’m making. I’ve talked to David Del Tredici about

this because he used in one of his pieces the same Bach chorale that Alban

Berg used in the violin concerto. Do you know that Chorale prelude?

It’s called Est ist Genug, and it

has a blue note it in it. I said, “David, I’ve always dug that blue

note,” and he said, “That’s not a blue note. That’s a modulation.

That’s not a lowered seventh, it’s a modulation into the subdominant.”

So in the key of C, he was hearing the B flat as already being in F and therefore

much more normally than I, who was hearing it as a blue note in C.

But beyond that, just as I can’t know if your blue is my blue, I can’t know

if my blue note is your dominant seventh.

NR: All teaching is hype, so I do it partly for

the money. Three-fourths for the money, and one fourth because

I’m fairly good at the mysterious process of what it is. You can really

teach anything in the world in the performing arts except the making of it,

because I can make anybody, any beginner, into a fairly decent pianist with

a little bit of technique. They might not play with what used to be

called ‘feeling,’ but they can get the right notes. But with composing

you can’t start from scratch. You have to take the person who is presented

as a composer and he has to have written something so you can tell him what’s

wrong with it. You’d be amazed at the number of famous performers

— a Horowitz or a Rubenstein or a Joan Sutherland,

who deal with music all their life — who, if you said

to them, “Write me a piece for tomorrow,” would become panic stricken.

They don’t know even how to begin writing a piece. Partly that has

to do with basic education, because we all know how to read and write, and

paint pictures in nursery school. We write poems, we rhyme cat with

rat; we paint pictures, make mud pies. They might be lousy mud pies

and lousy poems, but at least we do them. But the basics of musical

education — what does a note mean on paper, on a staff

— is not taught to beginners. If it were, music would be

less mysterious. Although, I must hasten to add, it is still mysterious

to me. I still don’t know what it means, and I still don’t know what

in it can move me or anybody else to tears. Nobody knows — nobody

— and I’m not a fool, and neither is Susan Langer, who spent her

life writing on the philosophy of music. I do know, though, what in

music will move me in a very cold, medicinal way. I can be extremely

moved by a major seventh, or secondary seventh chords, and by sequences in

Bach and in Ravel. I can be left utterly cold by dominant sevenths.

Speaking in terms strictly of harmony, what moves me is the acrid sharpness

of a minor second or a major seventh, or minor ninth that then resolves.

The resolution to me is heartbreaking. I hear a lot of Bach, which

has a great deal of that kind of resolution, exactly as I hear Ravel or Poulenc,

which also has those chords, and yet Bach never knew who Poulenc and Ravel

were. I hear the music very similarly. I’ve talked to Rosalind

Turek, for example, who plays more Bach keyboard music than anybody else,

and she doesn’t know what I’m talking about because she doesn’t know the

contemporary allusions that I’m making. I’ve talked to David Del Tredici about

this because he used in one of his pieces the same Bach chorale that Alban

Berg used in the violin concerto. Do you know that Chorale prelude?

It’s called Est ist Genug, and it

has a blue note it in it. I said, “David, I’ve always dug that blue

note,” and he said, “That’s not a blue note. That’s a modulation.

That’s not a lowered seventh, it’s a modulation into the subdominant.”

So in the key of C, he was hearing the B flat as already being in F and therefore

much more normally than I, who was hearing it as a blue note in C.

But beyond that, just as I can’t know if your blue is my blue, I can’t know

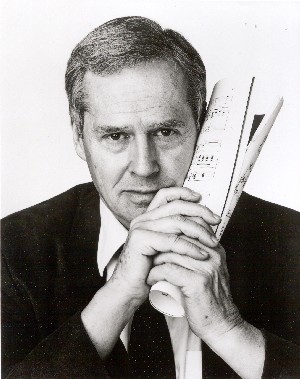

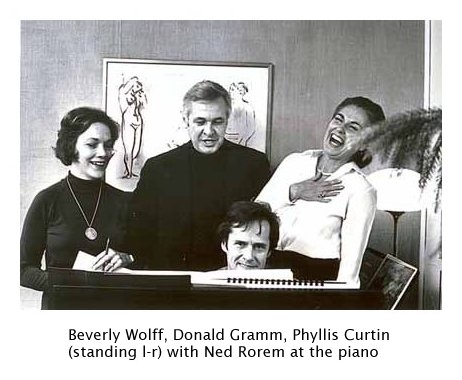

if my blue note is your dominant seventh. NR: Not that I have that many, but if I’m involved

in the recording I can be terribly pleased when there’s a playback.

I’ll say, “Oh, my God, isn’t it wonderful? We’ve got this down for

immortality.” Then when the record comes out, I never listen to it

again. It always upsets me and it’s never right. Performances

are never right. I think the songs of mine that Donald Gramm has sung

are absolutely flawless on records, and I’m very glad that Donald, who recorded

so very little, did them. [Vis-à-vis the photo at right, see

my Interview with Donald Gramm,

and my Interview with Phyllis

Curtin.] I don’t really like records of anybody’s music, and that

goes for mine, but yeah, I’m pleased with a lot of recordings.

NR: Not that I have that many, but if I’m involved

in the recording I can be terribly pleased when there’s a playback.

I’ll say, “Oh, my God, isn’t it wonderful? We’ve got this down for

immortality.” Then when the record comes out, I never listen to it

again. It always upsets me and it’s never right. Performances

are never right. I think the songs of mine that Donald Gramm has sung

are absolutely flawless on records, and I’m very glad that Donald, who recorded

so very little, did them. [Vis-à-vis the photo at right, see

my Interview with Donald Gramm,

and my Interview with Phyllis

Curtin.] I don’t really like records of anybody’s music, and that

goes for mine, but yeah, I’m pleased with a lot of recordings.| Words and music are inextricably

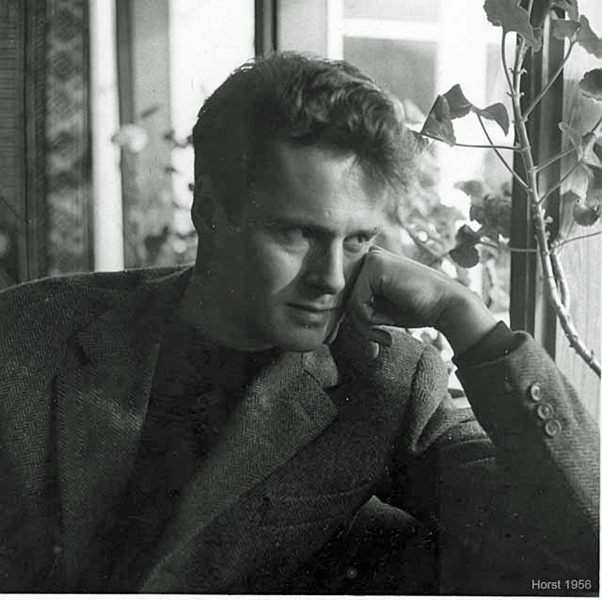

linked for Ned Rorem. Time Magazine has called him "the world's

best composer of art songs," yet his musical and literary ventures extend

far beyond this specialized field. Rorem has composed three symphonies, four

piano concertos and an array of other orchestral works, music for numerous

combinations of chamber forces, ten operas, choral works of every description,

ballets and other music for the theater, and literally hundreds of songs

and cycles. He is the author of sixteen books, including five volumes of

diaries and collections of lectures and criticism. Ned Rorem is one of America's most honored composers. In addition to a Pulitzer Prize, awarded in 1976 for his suite Air Music, Rorem has been the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship (1951), a Guggenheim Fellowship (1957), and an award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1968). He is a three-time winner of the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award; in 1998 he was chosen Composer of the Year by Musical America. The Atlanta Symphony recording of the String Symphony, Sunday Morning, and Eagles received a Grammy Award for Outstanding Orchestral Recording in 1989. From 2000 to 2003 he served as President of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2003 he received ASCAP's Lifetime Achievement Award, and in January 2004 the French government named him Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters. Among his many commissions for new works are those from the Ford Foundation (for Poems of Love and the Rain, 1962), the Lincoln Center Foundation (for Sun, 1965); the Koussevitzky Foundation (for Letters from Paris, 1966); the Atlanta Symphony (String Symphony, 1985); the Chicago Symphony (Goodbye My Fancy, 1990); Carnegie Hall (Spring Music, 1991), and the New York Philharmonic (Concerto for English Horn and Orchestra, 1993). Among the distinguished conductors who have performed his music are Bernstein, Masur, Mehta, Mitropoulos, Ormandy, Previn, Reiner, Slatkin, Steinberg, and Stokowski. Rorem is justly renowned for his art songs; his catalog includes more than 500 works in the medium. Evidence of Things Not Seen, his evening-length song cycle for four singers and piano, represents his magnum opus in the genre. The New York Festival of Song premiered the cycle at Weill Recital Hall of Carnegie Hall in January 1998. New York magazine called Evidence of Things Not Seen "one of the musically richest, most exquisitely fashioned, most voice-friendly collections of songs I have ever heard by any American composer;" Chamber Music magazine deemed it "a masterpiece." Rorem's most recent opera, Our Town, which he completed with librettist Sandy McClatchy, is a setting of the acclaimed Thorton Wilder play of the same name. It premiered at the Indiana University Jacob's School of Music in February 2007 and has enjoyed subsequent performances with the Lake George Opera and Aspen Music Theater Center, with future performances scheduled at the North Carolina School of the Arts, Opera Boston, and Festival Opera in Walnut Creek, CA. October 23, 2003 marked the composer's 80th birthday, highlighting a season of international festivities. Chief among them was the Curtis Institute of Music's "Roremania," a two-week celebration encompassing works in every genre. The birthday season brought a trio of new concertos from Rorem: Cello Concerto, commissioned by the Residentie Orchestra and the Kansas City Orchestra for David Geringas; Flute Concerto, commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra for its principal flutist Jeffrey Khaner; and Mallet Concerto, commissioned for Evelyn Glennie by the Madison Symphony Orchestra and the Eos Orchestra. His most recent publication, Facing the Night: A Diary (1999-2005) and Musical Writings, chronicles Rorem's dark journey after the death of 32 year companion, Jim Holmes. In his diary, Lies, (published by Counterpoint Press in 2000) Rorem said: "My music is a diary no less compromising than my prose. A diary nevertheless differs from a musical composition in that it depicts the moment, the writer's present mood which, were it inscribed an hour later, could emerge quite otherwise. I don't believe that composers notate their moods, they don't tell the music where to go - it leads them....Why do I write music? Because I want to hear it - it's simple as that. Others may have more talent, more sense of duty. But I compose just from necessity, and no one else is making what I need." Rorem was born in Richmond, Indiana on October 23, 1923. As a child he moved to Chicago with his family; by the age of ten his piano teacher had introduced him to Debussy and Ravel, an experience which "changed my life forever," according to the composer. At seventeen he entered the Music School of Northwestern University, two years later receiving a scholarship to the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. He studied composition under Bernard Wagenaar at Juilliard, taking his B.A. in 1946 and his M.A. degree (along with the $1,000 George Gershwin Memorial Prize in composition) in 1948. In New York he worked as Virgil Thomson's copyist in return for $20 a week and orchestration lessons. He studied on fellowship at the Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood in the summers of 1946 and 1947; in 1948 his song The Lordly Hudson was voted the best published song of that year by the Music Library Association. In 1949 Rorem moved to France, and lived there until 1958. His years as a young composer among the leading figures of the artistic and social milieu of post-war Europe are absorbingly portrayed in The Paris Diary and The New York Diary, 1951-1961 (reissued by Da Capo, 1998). He currently lives in New York City. Ned Rorem is published by Boosey & Hawkes. — February 2012

Reprinted by kind permission of Boosey & Hawkes. |

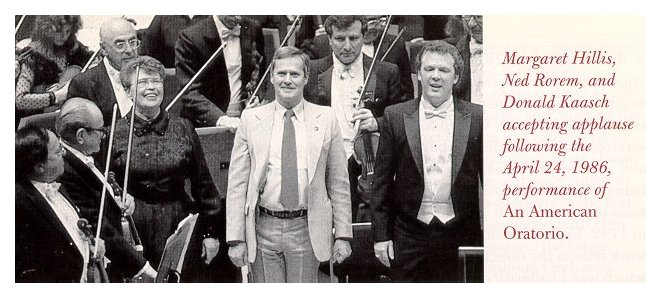

This interview was recorded in an office of the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra on April 24, 1986. Portions were used (along with

recordings) on WNIB in 1987, 1988, 1993, 1998 and 1999, and on WNUR in 2003.

It was transcribed and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.