Note: Three bios in three

languages with three different birth years!

Elen Dosia (1915 - May 15, 2002), born Hélène

Odette Zygomala, sometimes known as Ellen Dosia, was a French opera

singer of Greek origin.

Dosia

was born in Constantinople. She became a soprano singer, and enjoyed

her first major success at age 20 with the title part in Tosca.

She quickly became one of the most popular singers at Opéra

Garnier and

Opéra-Comique, where she performed from 1935 through 1952.

Before World

War II she was described as "the most popular singer in the world". She

appeared often in Massenet operas, performing in Manon and Thaïs, and appearing at the

June 1942 Massenet Gala singing the title role in a tableaux of Esclarmonde. Dosia

was born in Constantinople. She became a soprano singer, and enjoyed

her first major success at age 20 with the title part in Tosca.

She quickly became one of the most popular singers at Opéra

Garnier and

Opéra-Comique, where she performed from 1935 through 1952.

Before World

War II she was described as "the most popular singer in the world". She

appeared often in Massenet operas, performing in Manon and Thaïs, and appearing at the

June 1942 Massenet Gala singing the title role in a tableaux of Esclarmonde.

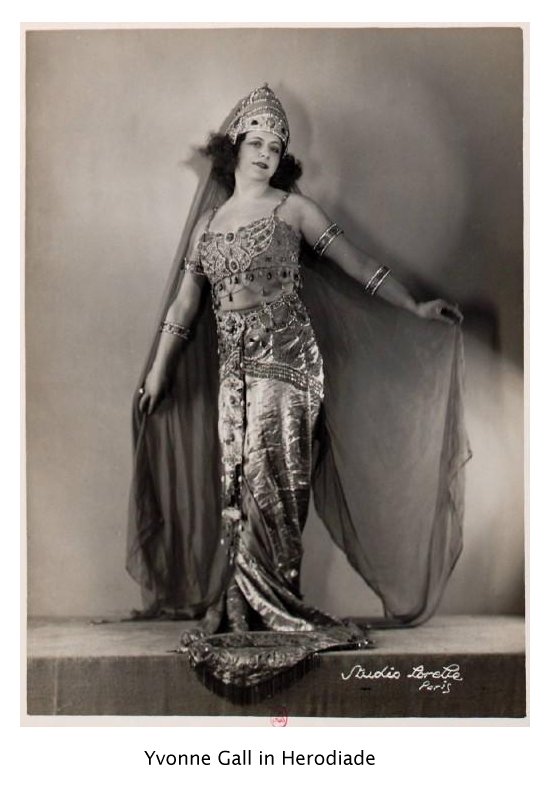

In 1951 she appeared in Of Men and

Music, a Fox film production, singing excerpts from Salome's

part in Hérodiade.

On November 15, 1947 Dosia debuted at the Metropolitan Opera as Tosca

to Jan Peerce's Cavaradossi and Frank Valentino's Scarpia with Giuseppe

Antonicelli conducting. Her performance was relatively poorly received;

reviews were critical, and after only five performances (in both Tosca and Manon, and as Mélisande in Pelléas et Mélisande

the following season), she retired from the stage in 1952. Thereafter

Dosia concentrated on her family life.

*

* *

* *

13.10. Elen DOSIA: 100. Geburtstag (2013) [October 13, 1913]

Sie kam als Kind nach Frankreich und wurde in Paris und Neuilly

erzogen; sie erhielt frühzeitig Tanzunterricht bei Loie Fuller.

Mit 16

Jahren begann sie das Gesangstudium, mit 18 kam sie auf das

Conservatoire National de Paris. 1936 debütierte sie an der

Opéra-Comique Paris als Tosca. Hier hatte sie große

Erfolge, vor allem

als Mélisande in »Pelléas et

Mélisande«, als Mimi in »La Bohème« und

als Titelheldin in Massenets »Manon«. An der Pariser Grand

Opéra

feierte man sie als Thaïs in der gleichnamigen Oper von Massenet,

als

Juliette in »Roméo et Juliette« und als Marguerite

im »Faust« von

Gounod. Sie heiratete den Tenor André Burdino (1891-1987) und

war mit

ihm zusammen 1937-40 an der Oper von Chicago engagiert. In Chicago sang

sie sehr erfolgreich Partien wie die Manon, die Juliette, die Giulietta

und die Antonia in »Hoffmanns Erzählungen« und gab

zusammen mit André

Burdino Konzerte. Sie gastierte in Brüssel, Prag, Zürich,

Belgrad,

Athen und Istanbul. 1939 sang sie in Scheveningen die Mélisande.

Während des Zweiten Weltkrieges trat sie an den beiden

großen

Opernhäusern von Paris auf. 1947-49 gastierte sie sehr erfolgreich

in

insgesamt fünf Vorstellungen an der Metropolitan Oper New York:

als

Tosca (ihre Antrittspartie), als Manon und als Mélisande. 1948

trat sie

an der Oper von Monte Carlo als Thaïs auf. 1952 nahm sie von der

Bühne

Abschied. Ihre große Bühnenkarriere verdankte sie nicht

zuletzt auch

der aparten Schönheit ihrer Erscheinung und ihrer eminenten

Darstellungskunst. Sie starb 2002 in Boulogne-sur-Seine. Ihre

schöne

lyrische Sopranstimme ist lediglich durch zwei Schallplatten der Marke

HMV überliefert.

*

* *

* *

Il y a tout juste un demi-siècle la cantatrice Elen DOSIA se

retirait

de la scène en plein succès après une

dernière interprétation de la

Tosca à la Salle Favart. Cette artiste brillante avait

été acclamée

dans les principaux théâtres du monde entier et ses

interprétations

restèrent longtemps gravées dans les mémoires des

amateurs d’opéras :

Thaïs, Grisélidis, Pelléas et Mélisande,

Roméo et Juliette, Othello...

Cinquante ans ont passé depuis, et le 10 mai 2002, à

Boulogne-sur-Seine

où elle vivait depuis de nombreuses années, cette gloire

des années

quarante s’en est allée rejoindre ses pairs au paradis des

musiciens.

Seul nous reste à présent, pour nous souvenir de sa voix

limpide,

parfaitement maîtrisée, l’enregistrement mémorable

en juin 1944 de

Thaïs de Massenet, avec Paul Cabanel, Georges Noré,

Huguette

Saint-Arnaud et Madeleine Drouot, sous la direction de Jules Gressier

(Malibran Music, CDRG 132).

Née à Constantinople le 13 octobre 1918, Odette

Hélène Zygomala

s’installait plus tard avec sa famille à Paris. Sans doute

descendait-elle de cette très ancienne famille grecque

originaire

d’Argos, puis de Nauplie, établie à Constantinople au

XVIe siècle ?

C’est par la danse qu’elle débutait l’étude des arts. La

célèbre

danseuse Loïe Fuller (1862-1928), artiste de music-hall

américaine

émigrée à Paris, qui inventa " la danse serpentine

" (utilisation de

longs voiles transparents éclairés de tous

côtés), lui enseigna l’art

du mouvement et de la comédie. Elle entrait ensuite en 1934,

à l’âge de

16 ans, au Conservatoire de musique et de déclamation et deux

années

plus tard en ressortait, trois premiers prix en poche : chant,

opéra,

opéra-comique. Cette même année 1936, en octobre

elle épousait le ténor

André Burdino (1891-1987) qui triomphait notamment dans Mignon.

Le

couple devra se séparer en 1943, mais entre temps la gloire

sourit à

Odette Zygomala, devenue Elen Dosia pour la scène. Un mois

après son

mariage, elle débutait à l’Opéra-Comique avec le

ténor italien Giuseppe

Lugo dans La Tosca de Puccini, qu’elle chantait encore en 1941 avec

Rouquetty et Cabanel. Ce 28 novembre 1936 fut le véritable point

de

départ d’un immense succès qui se confirmera au fil de

ses apparitions

sur scènes et qui lui valurent un engagement pour l’Opéra

de Paris le

29 avril 1939. Elle se produisait pour la première fois sur la

scène du

Palais Garnier dans le rôle de Gina de La Chartreuse de Parme

(opéra en

4 actes et 11 tableaux, livret d’Armand Lunel d’après Stendhal,

musique

de Henri Sauguet). Entre 1936 et 1951, Elen Dosia, vedette des

Théâtres

Lyriques Nationaux (Opéra et Opéra-Comique), joua tous

les plus grands

rôles de l’opéra. Parmi ceux-ci notons les ouvrages

italiens de Verdi :

la Traviata et Othello... et de Puccini : la Bohème

(Opéra-Comique, 22

novembre 1941, direction : Eugène Bozza) et la Tosca..., ceux de

Massenet : Grisélidis (Opéra, 30 octobre 1942),

Thaïs, Esclarmonde,

Hérodiade, Manon (Opéra-Comique, 13 juillet 1941,

direction : Gustave

Cloez) et bien d’autres encore : Marouf (Henri Rabaud), Les Contes

d’Hoffmann (Offenbach), L’Heure espagnole (Ravel), Roméo et

Juliette et

Faust (Gounod)... Elle participa également à plusieurs

créations, parmi

lesquelles Le bon roi Dagobert, comédie musicale en 4 actes de

Marcel

Samuel-Rousseau (poème d’André Rivoire), en 1938 à

la Salle Favart, qui

fera dire au musicologue Louis Laloy : " Mlles Vina Bovy et Elen Dosia,

l’une plus vive et l’autre plus tendre, ont toutes deux des voix

charmantes, et sont aussi fort agréables à voir, dans les

rôles de la

fiancée princière et de son humble, mais victorieuse

rivale. ", et en

janvier 1944 dans ce même théâtre,

l’opéra-comique Amphytrion 38 de

Marcel Bertrand (compositeur méconnu, auteur également

d’un drame

lyrique en 3 actes Sainte-Odile, donné à

l’Opéra-Comique en 1923),

d’après l’œuvre de Jean Giraudoux. A l’étranger on la

réclamait aussi !

Entre 1937 et mars 1940, avec son mari André Burdino, elle se

produisait dans les opéras de Chicago, San Francisco et Los

Angeles, et

plus tard effectuait des tournées en Grèce, son pays

d’origine, ainsi

qu’en Yougoslavie, en Tchécoslovaquie, en Suisse, en Tunisie, au

Maroc

et au Canada. En novembre 1949 elle débutait au Met de New-York

dans

Thaïs, puis fut engagée dans la Tosca aux

côtés d’Ezio Pinza, Raoul

Jobin et Martial Singher, et assura trois saisons successives. Au cours

de sa carrière Elen Dosia s’est produite avec les plus grands

chanteurs

de l’époque, notamment le ténor français Louis

Arnoult, l’acteur et

chanteur d’origine polonaise Jan Kiepura, le ténor italien de la

Scala

de Milan Giacomo Lauri Volpi, le ténor dramatique corse

José Luccioni,

le baryton français Jacques Jansen, célèbre pour

son interprétation de

Pelléas, le ténor américain du Metropolitan

Opéra Jan Peerce, le

baryton américain Lawrence Tibbett, interprète

légendaire de

Falstaff... Elen Dosia s’essaya aussi quelque temps dans le

cinéma,

entre autres dans L’Ange gardien du réalisateur français

Jacques de

Casembroot (1942), auquel on doit également L’Assassin est parmi

nous

(1934) et un film hollywoodien d’Irving Reis, Of men and music, "

Enchantement musical " tourné en 1950, genre très en

vogue à l’époque,

auquel participaient également Dimitri Mitropoulos, Jascha

Haïfetz et

Arthur Rubinstein.

En 1952, après son remariage avec un compatriote grec, M. Jean

Georgiadès, elle mettait volontairement fin à sa

carrière de cantatrice

internationale, notamment afin d’élever son fils Philippe.

Totalement

retirée du monde musical, Elen Dosia avait cependant tenu

à garder un

mince fil d’Ariane : elle fit longtemps partie du Comité

d’honneur de

l’Union des Femmes Artistes Musiciennes, au sein de laquelle elle

siégeait dans les jurys des concours de chant.

Pour clore ce bref portrait d’une grande artiste, ajoutons que le

spécialiste de l’opéra qu’est Jean Gourret, dans son "

Dictionnaire des

cantatrices de l’Opéra de Paris " (Albatros, 1987)

précise en outre

qu’Elen Dosia était une " musicienne raffinée, excellente

comédienne,

[et une ] femme ravissante. "

|

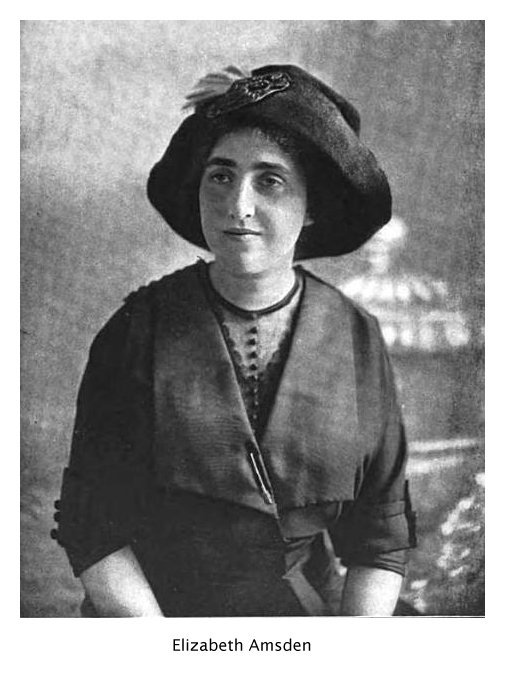

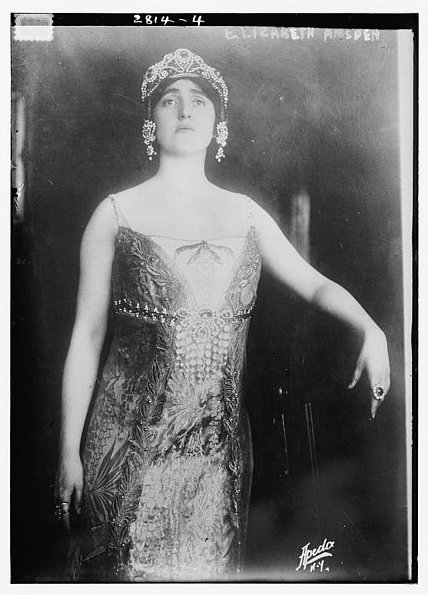

Elizabeth

Amsden

Elizabeth

Amsden

If

one should ask me what is the first consideration in becoming a success

as a singer, I should say the ability to criticise one's self. In my

own case I had a very competent musician as a teacher. He told me that

my voice was naturally placed and did very little to help place it

according to his own ideas. Perhaps that was well for me, because I

knew myself what I was about. He used to say, "That sounds beautiful,"

but all the time I knew that it sounded terrible. It was then that I

learned that my ear must be my best teacher. My teacher, for instance,

told me that I would never be able to trill. This was very

disheartening; but he really believed, according to his conservative

knowledge, that I should never succeed in getting the necessary

flexibility.

If

one should ask me what is the first consideration in becoming a success

as a singer, I should say the ability to criticise one's self. In my

own case I had a very competent musician as a teacher. He told me that

my voice was naturally placed and did very little to help place it

according to his own ideas. Perhaps that was well for me, because I

knew myself what I was about. He used to say, "That sounds beautiful,"

but all the time I knew that it sounded terrible. It was then that I

learned that my ear must be my best teacher. My teacher, for instance,

told me that I would never be able to trill. This was very

disheartening; but he really believed, according to his conservative

knowledge, that I should never succeed in getting the necessary

flexibility.

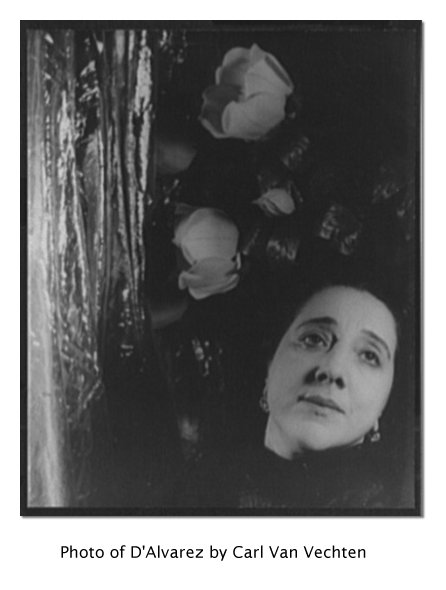

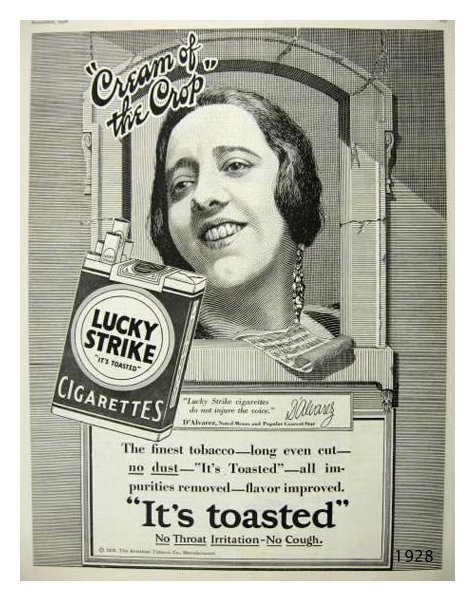

Following

her season in New York City, she went to London to help Oscar

Hammerstein inaugurate his London Opera in 1911; that year, she scored

great successes in French roles. D'Alvarez subsequently appeared at

leading European opera houses such as Covent Garden, and also sang in

Chicago and Boston. She made one film,

Following

her season in New York City, she went to London to help Oscar

Hammerstein inaugurate his London Opera in 1911; that year, she scored

great successes in French roles. D'Alvarez subsequently appeared at

leading European opera houses such as Covent Garden, and also sang in

Chicago and Boston. She made one film,

Dosia

was born in Constantinople. She became a soprano singer, and enjoyed

her first major success at age 20 with the title part in

Dosia

was born in Constantinople. She became a soprano singer, and enjoyed

her first major success at age 20 with the title part in

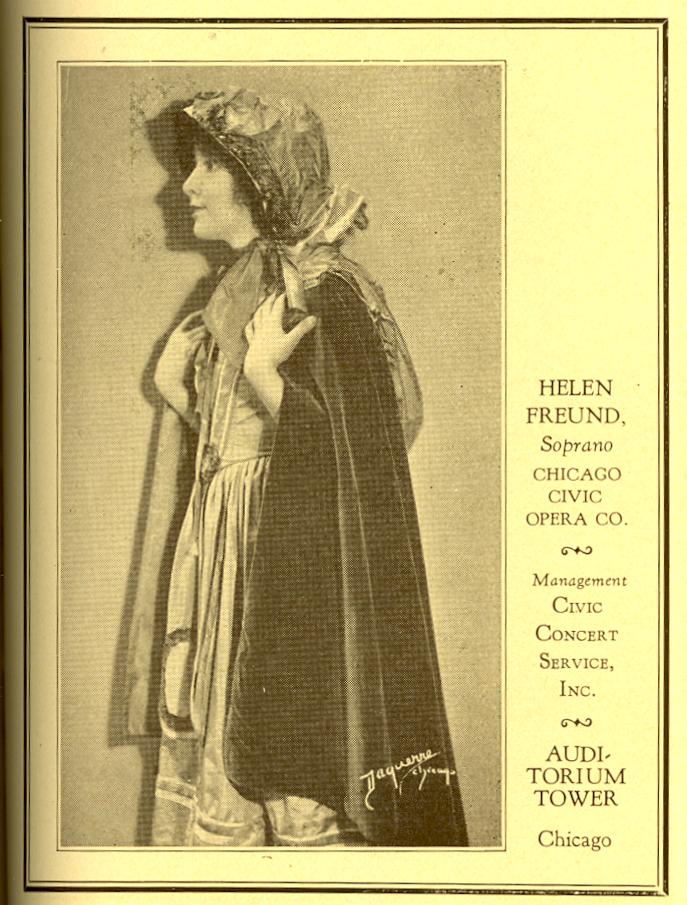

The second of the series of concerts for members of the

Civic Music Association will be given Wednesday. Jan. 5 in Spaldlng

Auditorium. The program will begin at the usual hour, 8:15 o'clock. The

Association is particularly fortunate in securing for one of the

recitals such artists as Alfred Wallenstein and Helen Freund. They are

preeminently American products and tho so young have made international

reputations. The success of these two young artists has been almost

phenomenal. The acclaim these musicians have received from critics and

public alike is based upon the recognition of real and actual

attainment, talent developed to the point of real genius. Alfred

Wallensteln, premiere 'cellist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, has

achieved a rare standing in the very highest rank of Master 'cellists.

Helen Freund, charming young soprano mado her debut two years ago in

the Chicago Opera Co with Mary Garden in "Werther." Her success was

instantaneous. Miss Freund has a good deal of common sense advice

gathered from her own experience, for young American girls who aspire

to operatic fame. The committee urges those members who find it

impossible to attend this recital to inform the secretary, Miss

Dickinson, so that other members desiring "guest" tickets will be able

to procure them.

The second of the series of concerts for members of the

Civic Music Association will be given Wednesday. Jan. 5 in Spaldlng

Auditorium. The program will begin at the usual hour, 8:15 o'clock. The

Association is particularly fortunate in securing for one of the

recitals such artists as Alfred Wallenstein and Helen Freund. They are

preeminently American products and tho so young have made international

reputations. The success of these two young artists has been almost

phenomenal. The acclaim these musicians have received from critics and

public alike is based upon the recognition of real and actual

attainment, talent developed to the point of real genius. Alfred

Wallensteln, premiere 'cellist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, has

achieved a rare standing in the very highest rank of Master 'cellists.

Helen Freund, charming young soprano mado her debut two years ago in

the Chicago Opera Co with Mary Garden in "Werther." Her success was

instantaneous. Miss Freund has a good deal of common sense advice

gathered from her own experience, for young American girls who aspire

to operatic fame. The committee urges those members who find it

impossible to attend this recital to inform the secretary, Miss

Dickinson, so that other members desiring "guest" tickets will be able

to procure them.

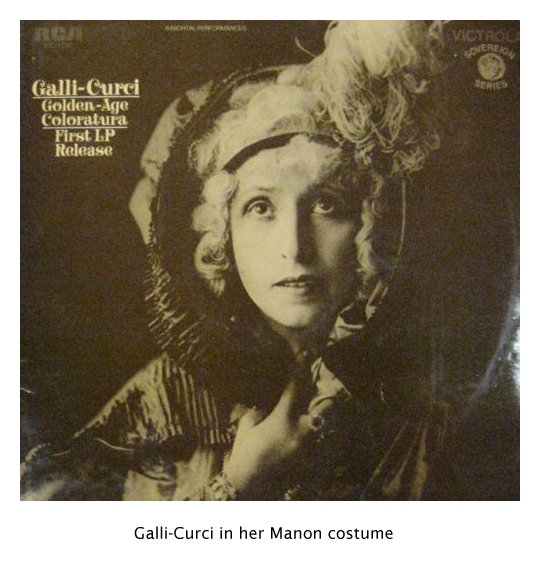

She

was born as Amelita Galli into an upper-middle-class family in Milan,

where she studied piano at the Milan Conservatory, winning a gold medal

and at the age of 16 was offered a position as a "professor" or teacher

there. She was inspired to sing by her grandmother. Operatic composer

Pietro Mascagni also encouraged Galli-Curci's singing ambitions. By her

own choice, Galli-Curci's voice was largely self-trained. She honed her

technique by listening to other sopranos, reading old singing-method

books, and doing piano exercises with her voice instead of using a

keyboard.

She

was born as Amelita Galli into an upper-middle-class family in Milan,

where she studied piano at the Milan Conservatory, winning a gold medal

and at the age of 16 was offered a position as a "professor" or teacher

there. She was inspired to sing by her grandmother. Operatic composer

Pietro Mascagni also encouraged Galli-Curci's singing ambitions. By her

own choice, Galli-Curci's voice was largely self-trained. She honed her

technique by listening to other sopranos, reading old singing-method

books, and doing piano exercises with her voice instead of using a

keyboard.

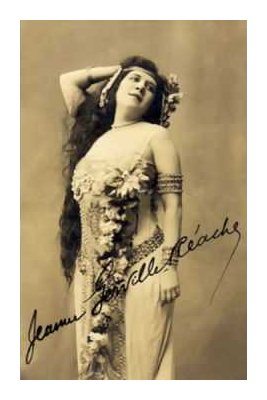

Jeanne

Gerville-Réache was born in Orthez, France. Her father was the

governor

of the French Caribbean islands Guadeloupe and Martinique, and she

spent her childhood in Martinique with him and her Spanish mother. She

studied in Paris under Rosine Laborde through whom she met operatic

soprano Emma Calvé, a former pupil of Laborde's. Calvé

arranged for

Gerville-Réache to make her professional opera début as

Orphée in

Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice at the Opéra-Comique in 1899.

Mezzo-soprano

Pauline García-Viardot coached her for this first production and

then

continued to teach her for the next several years.

Jeanne

Gerville-Réache was born in Orthez, France. Her father was the

governor

of the French Caribbean islands Guadeloupe and Martinique, and she

spent her childhood in Martinique with him and her Spanish mother. She

studied in Paris under Rosine Laborde through whom she met operatic

soprano Emma Calvé, a former pupil of Laborde's. Calvé

arranged for

Gerville-Réache to make her professional opera début as

Orphée in

Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice at the Opéra-Comique in 1899.

Mezzo-soprano

Pauline García-Viardot coached her for this first production and

then

continued to teach her for the next several years.

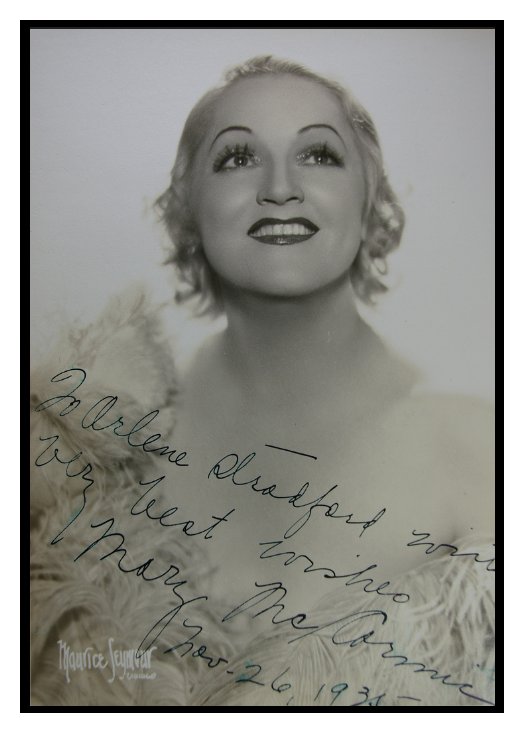

McCormic

was born in Belleville, Arkansas. A onetime obscure Arkansas housewife,

McCormic rose to stardom and enjoyed a colorful personal life — four

marriages and four divorces (men of no resemblance to one another),

almost a fifth, a high-dollar lawsuit defense for assaulting an

unauthorized female biographer, boom and bust personal wealth, witty

humor, and brush with royalty. McCormic captured world intrigue with

the panache of the operas she starred in, all with the backdrop of

being born at the end of the Gilded Age, growing up as a teenager

during World War I, flourishing as an opera superstar through the

Roaring Twenties, Prohibition, the Jazz Age, the Great Crash, and

failing in her last two high profile marriages in the throes of the

Great Depression. She died, in her eighties, in Amarillo, Texas.

McCormic

was born in Belleville, Arkansas. A onetime obscure Arkansas housewife,

McCormic rose to stardom and enjoyed a colorful personal life — four

marriages and four divorces (men of no resemblance to one another),

almost a fifth, a high-dollar lawsuit defense for assaulting an

unauthorized female biographer, boom and bust personal wealth, witty

humor, and brush with royalty. McCormic captured world intrigue with

the panache of the operas she starred in, all with the backdrop of

being born at the end of the Gilded Age, growing up as a teenager

during World War I, flourishing as an opera superstar through the

Roaring Twenties, Prohibition, the Jazz Age, the Great Crash, and

failing in her last two high profile marriages in the throes of the

Great Depression. She died, in her eighties, in Amarillo, Texas.

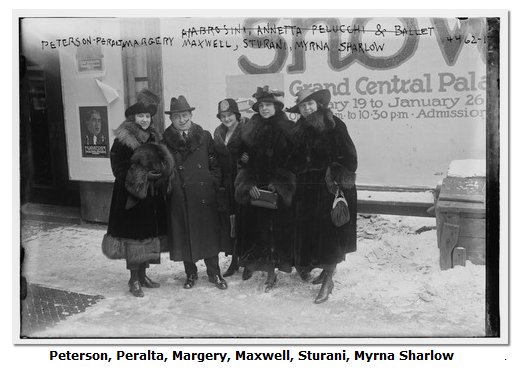

In 1920 Sharlow returned to the Boston Opera House

In 1920 Sharlow returned to the Boston Opera House

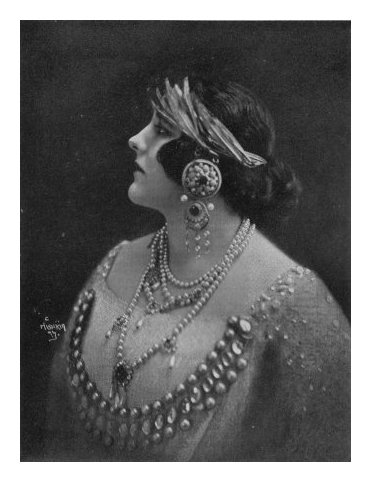

She made her stage debut in 1910 at the young age of 15

at the Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, Argentina in Stiattesi's

She made her stage debut in 1910 at the young age of 15

at the Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, Argentina in Stiattesi's

Vix

studied at the Nantes Conservatoire and then at the Paris Conservatoire

as a pupil of Lhérie where she won the first prize for opera in

1904

(as well as second prize for opéra comique). She made her debut

at the

Palais Garnier on 27 January 1905 in the title role in the premiere of

Vix

studied at the Nantes Conservatoire and then at the Paris Conservatoire

as a pupil of Lhérie where she won the first prize for opera in

1904

(as well as second prize for opéra comique). She made her debut

at the

Palais Garnier on 27 January 1905 in the title role in the premiere of

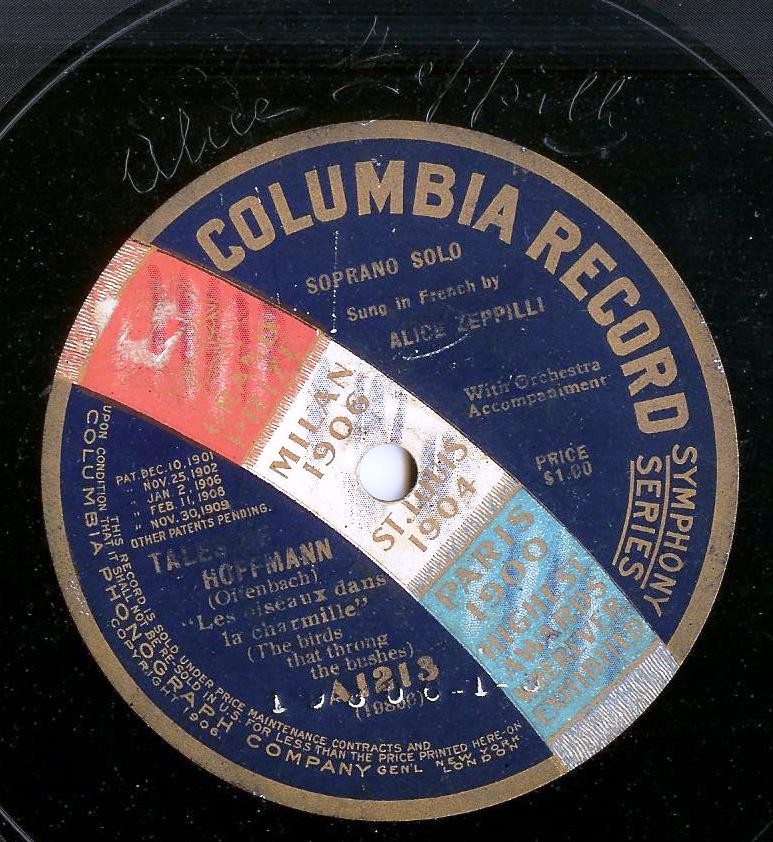

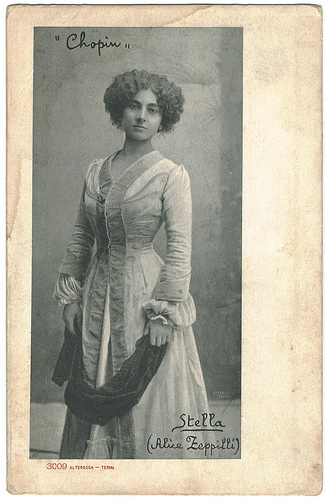

Zepilli

made her professional opera debut in Milan at the Teatro Lirico on 25

November 1901 at the age of 16 as Stella in the world premiere of

Giacomo Orefice's

Zepilli

made her professional opera debut in Milan at the Teatro Lirico on 25

November 1901 at the age of 16 as Stella in the world premiere of

Giacomo Orefice's  In

1909-1910 Zeppilli also performed at the Opéra-Comique in Paris

where

she made her debut as the title heroine in Léo Delibes'

In

1909-1910 Zeppilli also performed at the Opéra-Comique in Paris

where

she made her debut as the title heroine in Léo Delibes'