Composer / Pianist Robert

Muczynski

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

In mid-December of 1987, Robert Muczynski was back in Chicago to visit

his

sister. It was at her home that we met for our interview.

As we were setting up to begin the conversation, I was looking over the

stack of LPs he had brought for me to use on the air . . . . .

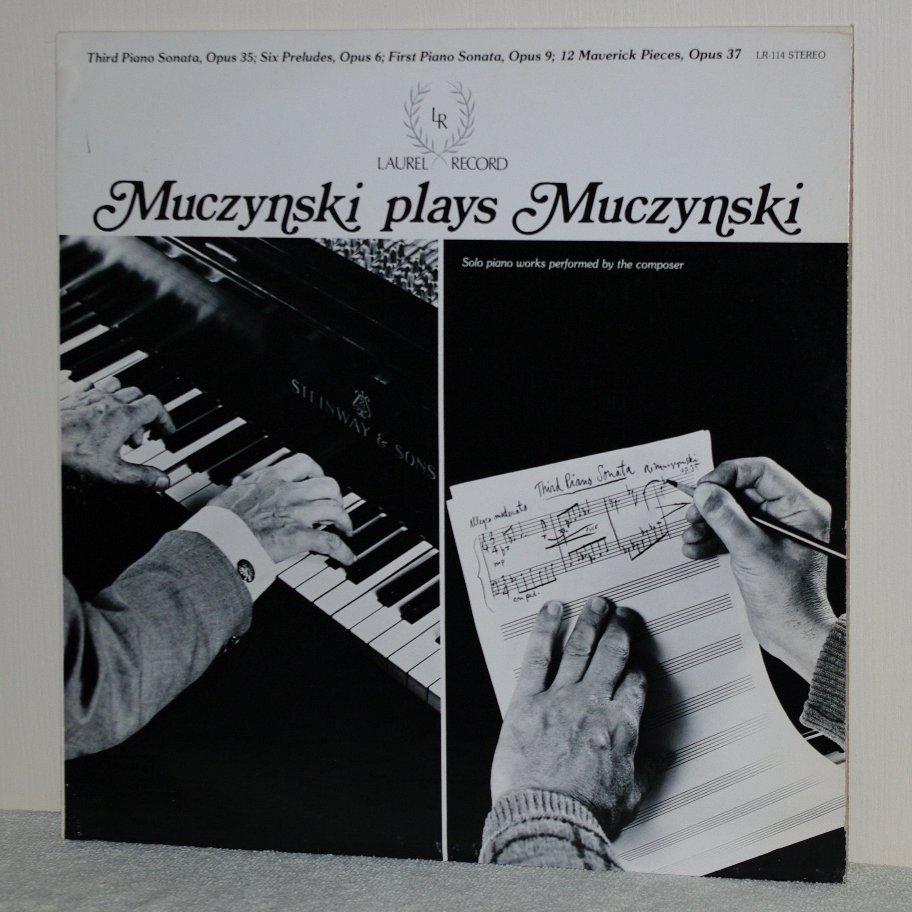

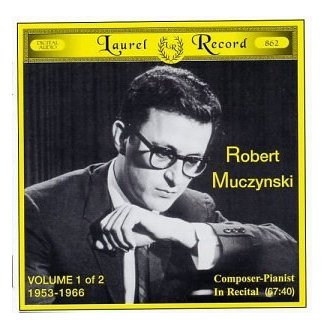

Robert Muczynski:

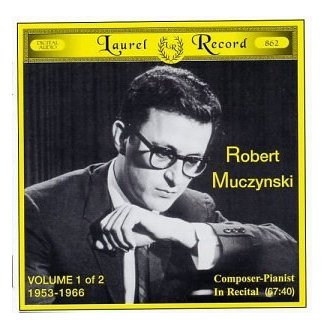

This record was the first encounter for me with the Laurel Record

Company. It was performed by the Western Arts Trio. They

commissioned piano trios of these three composers. Malcolm

Williamson is Master of the Queen’s Music in London, now. [See my

Interview with

Malcolm Williamson.] David Baker is at the University of

Michigan and he’s sort of a jazz-classical composer, and mine is the Second Piano Trio. I have

just finished a Third Piano Trio,

which they’re going to be premiering in January. Herschel [the

producer, Herschel Burke Gilbert] got the notion that he would like me

to record just about all of my solo piano music for his label, and

invited me to do so some years later. I did Volume One...

Bruce Duffie:

[Looking at the record and reading the title] “Muczynksi

plays Muczynksi.”

RM: That was

his idea. We didn’t do the things chronologically. For

example, this record has the Third

Piano Sonata and the First

Piano Sonata, and on Volume Two we did the Second Sonata.

BD: [Reading

a sticker on the back of the jacket] “This

record pressed with the new American Quiex Vinyl for extra quiet

surfaces.”

RM: His

productions are very fine. I was at Rose Records on Wabash a

couple of days ago and they had most of them there. [Picking up

another LP] This is with the Arizona Chamber Orchestra (who were

members of the U of A faculty), and I’m represented by two works

— Dance Movements,

which was commissioned by Thor Johnson back in ’63, and for this album

I wrote this short piece called Serenade

for Summer. There is also music of Bloch and

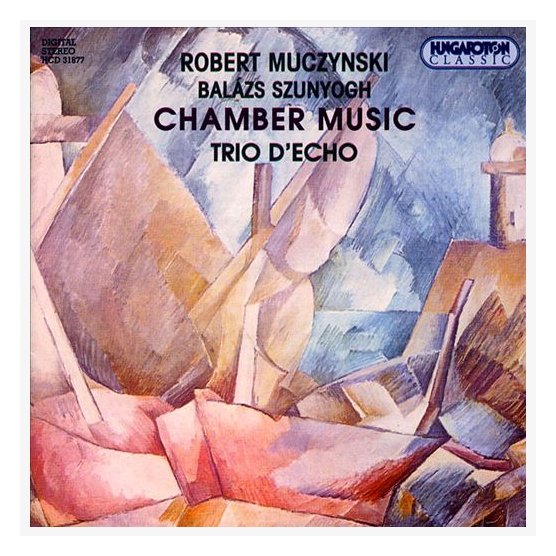

Creston. [Going to

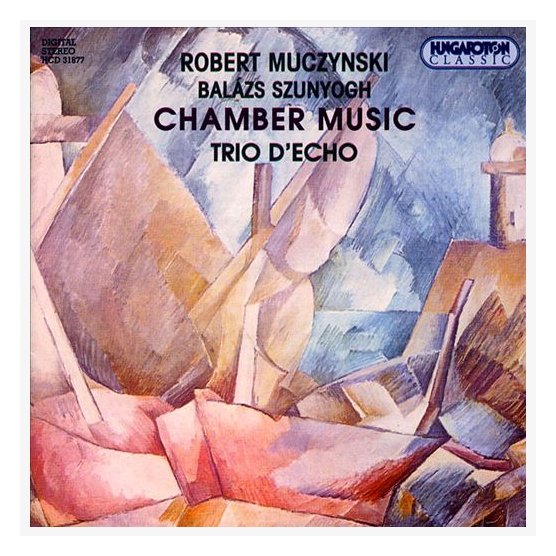

the next LP] Then this is an album of twentieth century clarinet

trios played by the Mühlfeld Trio, the resident trio at the

University of Washington in Pullman. They’re excellent artists

and they play superbly. This is one of my big chamber pieces, the

Fantasy Trio for clarinet,

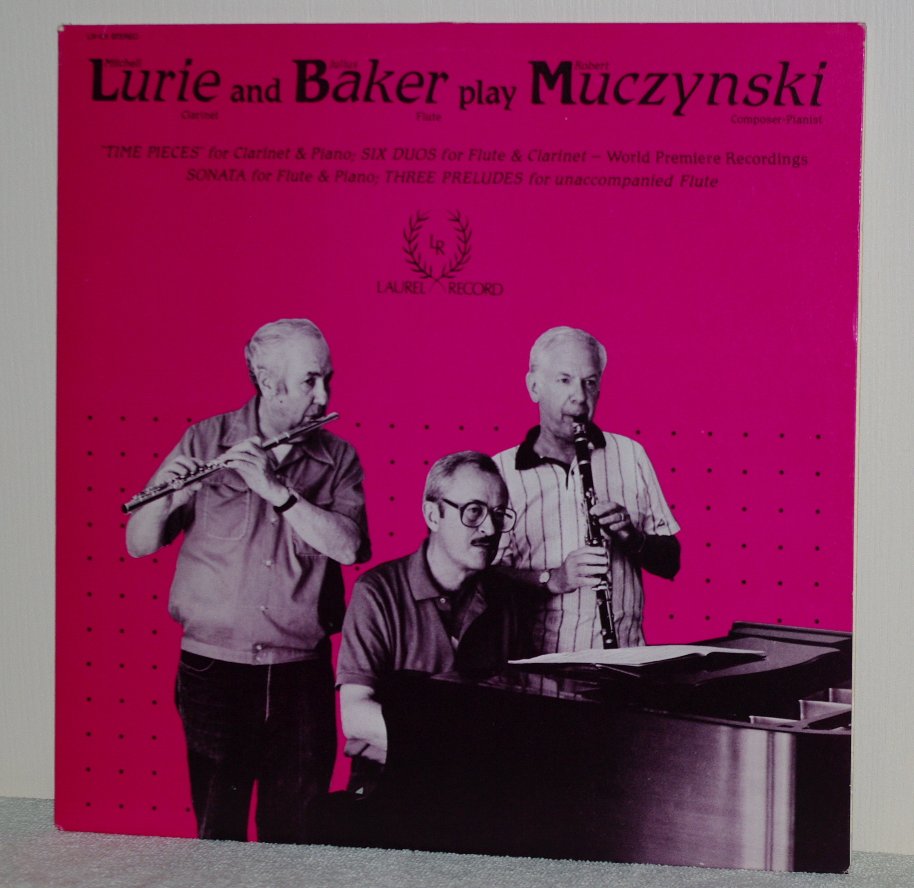

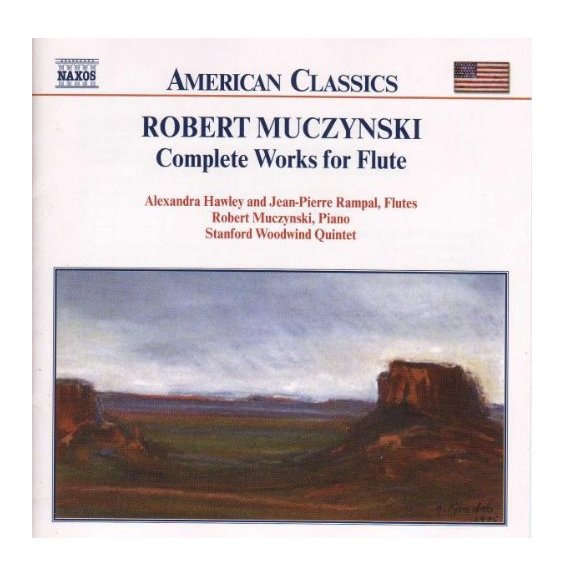

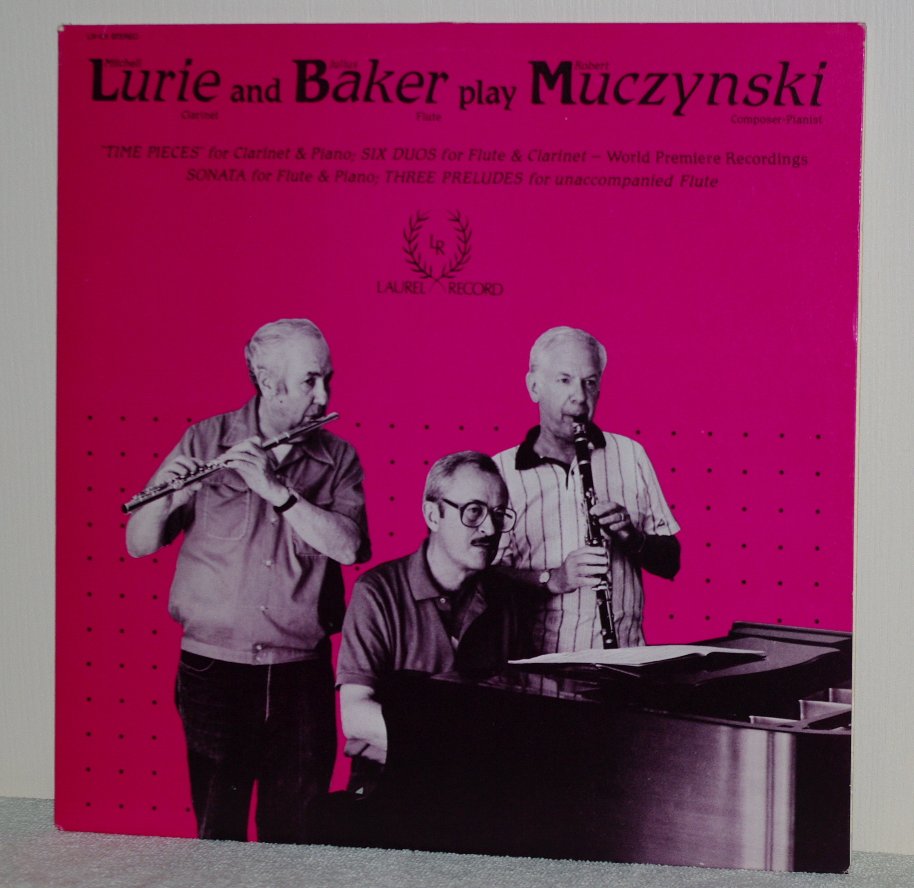

cello, and piano. [Picking up the next one] Then the most

current album has clarinetist Mitchell Lurie and flutist Julius Baker

playing the Time Pieces and

other works of mine.

BD: You’re

the pianist?

RM:

Yes. This was a big undertaking.

BD: You’re

also to soloist on the old Louisville record of the Piano Concerto. Are you

basically pleased with the recordings that have been made of your music?

RM: Basically

yes, I think I am. In a live performance you are somehow

permitted to drop a few more notes because it’s not frozen in

time. The most crucial and devastating thing about recording work

is that one cannot tolerate those mistakes on the record.

BD: Even the

slightest blemish must be corrected?

RM: I’m

afraid so. That’s the way it’s gotten.

BD: Is that

the way to do music?

RM: I don’t

know. It’s not up to me, though. [Both laugh]

Herschel seems to have a fixation about accuracy.

BD: Does he

also have a fixation about musicality?

RM: He is a

musician and has a fine ear, so I trust his judgment. It’s just

something we have to live with. I remember when I recorded the First Piano Sonata there was some

technical mishap with the equipment — which we

didn’t realize at the time — but when we went to

do the mastering it showed up. Something conked out and we

suddenly realized that we were not getting stereo. It was in

mono. That was a big, very difficult work for me to record, so

Mr. Gilbert said, “Would you like to do it over this afternoon?”

I said, “No. I’ll come back and do it another time.” I’m

glad I did, because when I did come back I was fresh for it. It’s

very difficult to record an album of solo piano music on which both

sides all totaled would be about an hour’s worth of music. That

one hour or so of music took about twenty-two hours of playing to get

it.

BD:

[Surprised at that amount of time] Really??? That much?

RM: It’s not

that I wasn’t prepared; it’s just that one has to be very

particular. Some of those takes were fine. There was

nothing wrong with them per se,

but you feel we perhaps can do better. There’s always that

striving. If you’re lucky enough to have four acceptable or good

takes, then you listen to those. In a maddening way, you make

that decision as to which is the best. It’s not that you’ve made,

necessarily, note errors.

BD: How did

you decide, then, to use one take over another?

RM: Here I’m

serving as both the composer and then the performer, sort of straddling

both. The problem for the composer is he has to be aware of what

needs to be done. He has to have his head on straight when

creating. He has to have this intuition. For example, I

think of composition as primarily a search and discovery act.

That’s really what it is — search and discovery,

and perhaps refinement after the discovery. When you’re searching

for this material, you’re actually inventing. Stravinsky said,

“I’m an inventor; I’m not a composer.” I think I understand what

he means. You’re inventing something that never existed. So

I think of it as search and discovery, and then when I’m putting myself

through that ordeal — it’s mostly an ordeal of searching for that

material — it’s either “yes, I like it,”

“no, it’s terrible,” or “maybe

there’s something there.” So to me, it

falls into three cut and dried sections. The easiest, of course,

are “yes” and “no”;

those are the black and white. The most torturous ones might be

the “maybes,” because you

feel — your intuition tells you — there’s

something there that’s worth salvaging or sifting out.

BD: Is that

where most of the music lies — in the “maybe”

category?

RM: Quite a

bit, I’d say. I wouldn’t know what percentage. It depends

on the material; that’s another factor. In the sifting process in

the “maybe” music, one has

to discover what it needs. That’s what a composer has to know how

to do, or we hopefully have trained ourselves to do. Many things

must come into play. You must think there’s something there, but

it’s sort of a diamond in the rough. I hope it’s a diamond,

anyway. You figure out what needs to be done. Perhaps the

note values are wrong. Perhaps the rhythm is off. Perhaps

there are many notes and some have to be sifted out or removed.

It is that kind of polishing. Then you can shape that. You

have to take the idea and shape it into something coherent and

seemingly spontaneous. I think that’s where the art is. If

there is an artistic thrust, that’s where it shows up — in

the ability of the composer or the creator to make a primitive

statement, to polish it in such a way that it appears to have come to

him out of the heavens in a pure state. So he must remove the

impurities and make that statement pure.

BD: When

you’re working with a piece of music — or even

just a part of a piece of music or a phrase — how

do you know when it is right, when to put the pen down and say, “That

part’s done”?

RM:

[Laughs] Unfortunately some of us don’t, and the music goes out,

perhaps, ten or fifteen minutes too long. I can think of many

living and dead masters that I could accuse if I wished to. I

prefer to lean toward the more succinct or terse kind of writing.

I just feel there is no point in padding this piece. If I’ve made

my statements, then let’s get off and that’s it. I prefer that to

huffing and puffing. Upon completing a lengthy work — let’s

say a sonata or whatever — you’ve faced all of

these problems that have come up. Problem after problem has come

up, and you have solved those musical problems. You’ve made all

these decisions and you’ve reached the end of the piece. Then you

decide some time later to face the next piece. The frustration is

that all of those problems and all of those solutions to those problems

that you encountered in the previous piece you can’t apply that to the

next piece because very frequently the problems do not match.

They’re not the same, nor are the solutions. So it’s always very

new, and perhaps that’s what makes it exciting. It is always an

adventure when you undertake the next piece.

BD: Are you a better

composer because you are also a performer?

BD: Are you a better

composer because you are also a performer?

RM: I don’t

know about that, although I do not like that old saw that so many toss

around, that composers don’t play their own music well!

[Both laugh] I don’t think that’s necessarily true.

BD: Do you

play your music well?

RM: As well

as I can! [Laughs] But there have been some superb, I mean

really superb, performers. I’m just thinking right off the top of

my head, Rachmaninoff is one the foremost examples of a superb

performing artist and composer. I have not perhaps heard

recordings of all of them playing, but most of the composers I can

think of are pretty good pianists, I believe. So as to whether or

not it makes you a better composer, I would only guess that because my

instrument is piano or the keyboard, I feel that I do at least write

better for the piano than I would have had I not had that

experience. In my composition students, for example, I can

generally tell when a person is not acquainted with the keyboard

because very awkward things emerge. It’s not that they’re

difficult; that’s another thing, but it’s just non-pianistic.

BD: Should

piano music be pianistic?

RM: Yes, I

think so.

BD: [With a

gentle nudge] Really? It shouldn’t be just music that

happens to be played on a piano, instead of, say, an orchestra?

RM: For me to

say what it should be would be awfully pompous. It depends on the

direction you’re taking when you’re writing. For one thing, I’ve

done a piano concerto many years ago. The thing I dislike about

so many piano concertos is that so many composers feel

duty-bound. They’re thinking they’re writing this for a master,

virtuoso soloist who wants to show his stuff or her stuff, so they feel

duty-bound to write the most fiendishly difficult, virtuoso

passages. To me that is too bad because it gets in the way of the

music very often.

BD: Then for

whom do you write — for yourself, for the

audience, for the people who commission it, for posterity?

RM: I don’t

know if there’s a posterity. I hope I’m writing for today.

Of course I write for myself. I think we all write for

ourselves. I’m certainly hoping that my music will touch someone,

or communicate with someone in the audience. A composer needs

feedback. He needs a performer; he needs an audience.

A composer has needs. We all have needs, and that often brings up

that question as to whether, if you were the only living person on the

planet, would you continue to write your music?

BD: Well

would you?

RM: I’m not

the only person living, so I don’t know! [Both laugh]

BD: But if

you were on a desert island, or on a deserted planet, would you

continue writing music?

RM: I don’t

think so.

BD: What

would you do?

RM: Swim and

try to find somebody else! Then I’d start writing again.

[Laughs] There have to be two, two to tango, and all that.

Is this adding up? It’s very difficult to verbalize some of these

things.

*

* *

* *

BD: You’ve

been teaching for a long time. Do you find that you learn things

as much as your students learn things, just by going through the

process so many times?

RM: Yes,

because in teaching you must nail down everything. You have to be

partly a dreamer — I mean hang onto your dream state — but

you must also verbalize. You must try to find the way to express,

or get across to your students just what it is that is required of a

composer, whether a young or old composer. There are certain

basics that have to be learned or assimilated and communicated. I

remember my teacher, Mr. Alexander Tcherepnin. When I brought my

earliest pieces in he would say, “These are very primitive pieces, but

somehow I find that attractive. I like it. Too often, when

a composer gets older he tends to get too complex and withdrawn, and

tries to get too sophisticated.”

BD: Do you

warn your students against this?

RM: There’s no

point in warning students about anything! [Both laugh] I

tell them, “I don’t have the stone tablets, but you’ve come to study

with me and you must trust my judgment. Otherwise, why come to

me? I will just call the shots. I will just tell you from

my own experience. I’ll call it the way I see it or hear it, and

then you can either take it or leave it, whatever I say.”

RM: There’s no

point in warning students about anything! [Both laugh] I

tell them, “I don’t have the stone tablets, but you’ve come to study

with me and you must trust my judgment. Otherwise, why come to

me? I will just call the shots. I will just tell you from

my own experience. I’ll call it the way I see it or hear it, and

then you can either take it or leave it, whatever I say.”

BD: Is

composing something that can be taught, or must it be innate within

each young composer?

RM: There has

to be the talent. I remember when Aaron Copland came to the

University of Arizona in 1979 in the Artist’s Series, he spoke to the

composition students. One of the students raised his hand and

asked Copland, “In addition to great talent, what in your opinion is

the most important thing a composer should have?” and Copland said,

“Tenacity.” I agree with that. It’s no place for wimps if

you’re going to be shattered and destroyed by a bad review or a

rejection slip from a music publisher. You just have to develop a

thick skin and just carry on. I think that is not only true of

music, but any profession.

BD: During

the thirty years you have been teaching, has the raw talent that’s been

coming to you been getting better? Is there any direction that

you’ve been seeing as you draw a line over thirty years?

RM: It

fluctuates, but I would say that the most difficult period was during

the Vietnam years.

BD: Just

because of the whole situation?

RM:

Yes. There was a very ugly feeling in the air, an

anti-establishment attitude. You could almost taste it.

BD: Have

we’ve gotten over that now?

RM:

Yes. It’s just the total extreme now. I have students

writing these very passive, pastoral, slow pieces. Not that I

can’t get anyone to write other styles, but most students tend to write

slow, expressive music — which is fine — but I

can’t get anyone to cut loose and do something audacious or fast music

with allegros.

BD: I wonder

why?

RM: It’s

easier to write slow music, in a sense. Not to be facetious about

it, but let’s say you sit down and you write a hundred measures of adagio or lento or largo — slow music. So that

piece, then, for that reason, because of its tempo being slow, those

hundred measures will probably last maybe eight minutes, or whatever

it’s going to be for that one movement. Now a hundred measures of

all allegro or presto music will go by in fifty

seconds, or something like that. That’s what I admire so much in

composers such as Martinů, because he loved to write those allegros. It’s so difficult

to sustain that, to do that.

BD: Are the

students looking for more result, just to have a longer piece of music,

just to have something more there with the same amount, or even less

work?

RM: I don’t

really know. I’ve taught composition on a classroom basis, which

is impossible. I prefer it on a one-to-one basis. But I

remember Tcherepnin telling me about the ratio of receiving an enormous

talent, which he thought was one student every ten years.

BD: Have you

had your three?

RM: I’ve had

two. [Both laugh] Maybe three, but just because one speaks

of an enormous talent doesn’t preclude that that person is going to go

out and pursue it. There have been people vastly talented that

I’ve taught, who unfortunately for one reason or another decided not to

pursue the profession.

BD: They put

their talent elsewhere?

RM:

Yes. One is operating a pizza parlor.

BD:

[Genuinely disappointed] Do you think he’s really getting as much

reward operating a pizza parlor as he was getting notes on the paper

and sounds out of instruments?

RM: I hope

so, but it’s a very tough profession. There are many young people

who become bitter. I don’t mean to be discouraging about this,

but we’re turning out young musicians like sausages, and we’ve reached

the saturation point. Where are all these people going to

go? There are only so many teaching positions. There are

only so many symphony orchestra positions. There’s only room for

so many in the big leagues on the concert stage. On the other

hand, what has not really been investigated and what I find very

exciting, at least from where I stand, is that with the spillover, not

everyone can be in New York or in Chicago or in San Francisco — these

big league places, cities, artistic capitals. So as a result, the

smaller towns, in some cases the so-called boondock places, are opening

their arms, and many of these very fine, beautifully trained musicians

and talented people, are being assimilated. They are serving

those communities and working with and training young musicians, and

sharing their knowledge and their training.

BD: Has the

propensity of recordings, and the availability of television and radio

everywhere helped this?

RM: Oh, I

think so, yes.

BD: Are you

optimistic about the whole future of music?

RM: In what

respect?

BD: Well,

let’s break it down into two large sections — the

creating and the performing. Let’s start with creating.

RM: I got

very discouraged somewhere back in the sixties or so. I was never

one to write an off-the-wall type music. I didn’t mind if that

was somebody else’s bag, but I just didn’t feel that was what I trained

myself to do, and I didn’t feel that I could honestly change my

fingerprints and go that route. I wondered what kind of artistic

integrity is that if I just chuck everything and say, “That was all

wrong. I’m going in this direction now.” So I’ve never been

trendy. I just am interested in good music, however it’s done,

whether it’s good jazz, or good concert music and so forth. But

there is no question that was a very difficult period for composers

such as myself who showed more of a traditional bent in their

writing. We were snubbed or disdained for still writing melody,

and having the nerve to use rhythm and counterpoint and all those

old-fashioned things.

BD: But you

had the tenacity to stay in there!

RM: I guess I

did, but others did, too. But there was this feeling in the air

that if you didn’t go a certain direction, then you were out of the

picture.

BD: When

you’re writing a piece, are you in control of it or is it in control of

you?

RM: Are you

asking me which is preferable?

BD: No, I’m

asking which is taking place.

RM: It goes

both ways, really. Sometimes, initially when you’re doing the

search work you feel nothing is coming. Maybe there are days and

maybe weeks when nothing really emerges. Then suddenly, sometimes

when you least expect it, something will pop out and you’ll say, “Oh,

there it is!” Then you start doing that detective work as I call

it. Mozart and Schubert, those wonderful, supremely gifted people

could do it all at once, but most of us have to forge our music as so

many musical links. Perhaps eight measures or ten measures will

come to you in a chunk, in a pure state where you won’t have to sweat

it, but most of the time the job is to assemble that piece in such a

way that it gives the illusion of being a spontaneous thought; as

though you just sat down and did it as an improvisation.

Improvisation and composition — I’m sure they’re not one and the

same. I admire improvisation, but the procedures are very

different. I think of improvisation as more akin to what it would

be for a performer who is sight reading — something

impromptu in

the rough. That is improvisation; it has to be done right on the

spot, whereas composition is something you have to ponder. You

have to let it gel. You have to let it mature, just as a

performer who is performing for the concert stage, playing at Orchestra

Hall or wherever has to prepare that in such a polished state that

there’s hopefully no slip-up.

BD: Is the

public becoming too acclimated to the perfect recordings, and then

expecting that same perfection in the concert hall?

RM: There was

a period of that, but I don’t know if that’s so prevalent today.

I tell performers that I’m not a devotee of safe performing or safe

playing — at least of my own music, or even of

other people’s music. I like the excitement of somebody walking

the tightrope and taking chances. I’m just speaking of my own

instrument, the piano. There are ways of negotiating passages

that nine times out of ten — or ten times out of

ten — you’ll play them accurately, but somehow

they come off bloodless. I’ve heard recordings of Shostakovich

playing his music, and sometimes there are physical inaccuracies, note

errors, but the playing is so damned exciting that it just thrills me.

BD: So you

want some life in your music?

RM: Yes, it

has to have sweep. It has to have blood. Unfortunately I’ve

heard many performances of my music where I’ve felt it needed a

transfusion! I would like to have helped it along, and I have to

be honest and say that sometimes I mess up. We all have off

nights. When I’ve played my own music in public sometimes I have

not been fully happy with the way I did something.

BD: But are

there other nights when you’re overjoyed and ecstatic about it?

RM:

Yes. It has something to do with full moon, and, I suppose,

energy level and what you ate and how you slept and who knows what else.

*

* *

* *

BD: Is

composing fun?

RM: It’s very hard

work. Certain kinds of pieces are fun. I’ve written many

collections of short pieces, or miniature pieces, and I like to do

those. It’s the type of writing that Robert Schumann did so much

of. Even his larger-scale pieces give the illusion of being

large-scale pieces structurally; I’m thinking of pieces like Carnaval and Kreisleriana. They’re really

short pieces sewn together. Or Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition where you

have lovely short pieces unfolding. They are very satisfying, and

there’s a great deal of variety and color there. It’s a nice

journey. I like to do that kind of writing, especially after

having worked for nine months on one piece where you have to wait about

eight to nine months before you see the end of the tunnel. You

think, “God, will this piece never come to an

end? Will I never

finish this piece?” In that lecture he gave

here, Copland said,

“For most of us, it’s no big deal to come up with two minutes or three

minutes of new music. But if you’re aiming to write a piece

that’s twenty-five, thirty-five, forty minutes, then you’ve got to know

how to fill up that musical canvas.” Canvas is a good word

because I’m an amateur watercolorist. I know the problem.

When I sit down with paper the size of piece of typewriter paper, I put

my subject in the center. The painting I do is usually very

square, and then I think, well, there it is. I look all around in

the border, and I think I’ve got all this space here. It’s not

filled in. How do I fill that in?

RM: It’s very hard

work. Certain kinds of pieces are fun. I’ve written many

collections of short pieces, or miniature pieces, and I like to do

those. It’s the type of writing that Robert Schumann did so much

of. Even his larger-scale pieces give the illusion of being

large-scale pieces structurally; I’m thinking of pieces like Carnaval and Kreisleriana. They’re really

short pieces sewn together. Or Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition where you

have lovely short pieces unfolding. They are very satisfying, and

there’s a great deal of variety and color there. It’s a nice

journey. I like to do that kind of writing, especially after

having worked for nine months on one piece where you have to wait about

eight to nine months before you see the end of the tunnel. You

think, “God, will this piece never come to an

end? Will I never

finish this piece?” In that lecture he gave

here, Copland said,

“For most of us, it’s no big deal to come up with two minutes or three

minutes of new music. But if you’re aiming to write a piece

that’s twenty-five, thirty-five, forty minutes, then you’ve got to know

how to fill up that musical canvas.” Canvas is a good word

because I’m an amateur watercolorist. I know the problem.

When I sit down with paper the size of piece of typewriter paper, I put

my subject in the center. The painting I do is usually very

square, and then I think, well, there it is. I look all around in

the border, and I think I’ve got all this space here. It’s not

filled in. How do I fill that in?

BD: Do you

fill it in, or cut off the space?

RM:

[Facetiously] I take a Brillo pad and dip it in the paints, and

do this in desperation. [Taps the table as if dabbing the pad onto the

paper] [Both laugh] Maybe I do that musically, too...

No, I don’t, but it’s a problem that young composers in universities or

colleges face. I remember that my big hang-up was how to face

writing a piece in a large form. When I did the first or second

piano pieces that I wrote for my teacher at the university, he said,

“This is very nice, but you’ve got enough different ideas on this one

page for about ten different pieces.” He went back to the first

four or five measures and said, “You should have taken this material

and developed it, but instead you ran out of steam suddenly, and then

you jump and go into something else. So it’s like a broken

sentence, rather than one whole coherent sentence that’s developed.”

BD: Was he

right?

RM: Yes, and

it was important to be told that, to be made aware of that.

BD: Do you

ever go back and revise your scores?

RM: Just

about never. It’s not a conceit, it’s just that when I’m writing

the pieces I’m so very particular while I’m doing the writing, and it

takes such a long time to do it that I’m not sloppy. That doesn’t

mean that the end result is a masterwork, but it’s got to be of a

certain standard, and it’s got to pass my security.

BD: Do you

feel you’re part of a line of composers, a lineage of composers?

RM: I don’t

think in those terms, no, but people are always bound to make

comparisons. So many music critics, if they don’t know a

composer, an unknown or relatively unknown composer — such as when I

was in my twenties — then they say, “Oh, it sounds like this. It

sounds like that. It sounds like this one.” But the only

way to really get a handle on a composer is to know virtually his whole

body of work; to get an overview of where he’s been, not just by one

isolated piece or two pieces, but to look at and listen to just about

everything he’s done... if that’s possible.

BD: How can

that be with the composer who’s only written a handful of pieces thus

far?

RM: I’m

speaking about later on, because there are critics who are not

acquainted with the more mature composers, who’ve been around for

thirty years, frankly.

BD: You’re an

American composer. Is there anything about your music that is

particularly American, or is it just music?

RM: That

reminds me of something that Virgil Thomson is supposed to have

said. “If you want to write American music, and if you are

American, all you have to do is sit down and write any kind of music

you damn please.” [See my Interview with Virgil Thomson.]

There are only so many cowboy tunes around and so many jazz licks

around and so many piano rags around. I can’t believe that is the

whole act for American music. Those things are charming and

that’s part of the American scene, but we’re talking about a melting

pot kind of country. My grandparents came on the boat through

Ellis Island, as so many did. Look at all the foods we

have. What is American food, you might say. Pizza is now

American food. Pizza is supposed to be the most popular American

food now, but it wasn’t born in America. It blossomed in America.

BD: Is this

what’s happening to our music, it’s blossoming in America?

RM: I hope

so. It goes through this metamorphosis. That’s what’s

happened in the last fifty or sixty years with the very early

composers. Edward MacDowell’s music has a very German technique

and it sounds sort of like Franz Liszt. Then where did Gershwin

come from, one wonders. That was a very big original. Many

of us have wondered where Gershwin would have gone, what direction he

would have taken had he still been living into his later years.

He was so young when he left, and so red-hot talented. A composer

starts with a model. Ravel used to tell his students, “Imitate

somebody you like. Choose somebody you like and imitate that

person. Then if you have something personal to add to that,

you’re one of the lucky ones.” I think that’s good advice.

I think that’s all we can do. For a long time there was this

quest for originality. I’m not an innovator; I’m not a pioneer, a

trailblazer, any of those things. But I am probably closer to a

kind of philosophy I just read not long ago. Francis Poulenc was

accused of not being an original or an innovator, so he said, “I like

to think there’s room in the world for composers who borrow other

composers’ chords.” Yet when I hear Poulenc’s music, I can spot

it like that. [Snaps fingers] When I hear Brahms’ music, I

realize here is a composer who never invented a new chord

himself. Yet he used everything that was passed down, and there

he is; he jumps out at you. What is it? For me, it’s the

strength of the personality, something distinctive in that personality,

and the ability of the composer to project that personality in such a

vivid way in musical terms. Of course that manifests itself in

various ways. We all have our favorite intervals. We all

have our favorite little thises and thats. It’s the way we use

those things, ultimately, that makes us sound individual. It’s

not by crashing your elbows on the keyboard or jumping off a ladder

onto the strings. That’s fun, maybe, but that’s not original.

BD: So what, for

you, is the ultimate purpose of music in society?

BD: So what, for

you, is the ultimate purpose of music in society?

RM: I’m sorry

to quote so many different people who are more brilliant than I, but I

just thought of Oscar Wilde’s famous quote. He said, “All art is

absolutely useless.” Of course he was being facetious and

audacious, but I understand what he means.

BD: So what

does he mean?

RM: I’ll tell

you another more current quote to answer that. Spencer Tracy was

supposed to have said, “Acting, that’s nothing. Anybody can do

that. Plumbing is important.” In other words, what is

needed, I mean really needed in terms of living. We have to have

food to subsist or survive.

BD: Do we

have to have music?

RM: Some

people don’t seem to have to have music, but everyone has to have

food. I cannot speak for others, but I would say it would be very

dreary for me without music or without painting or without

beauty. I’ll just hark back to about fifteen years ago when I was

talking about these things in an orchestration class. I told them

about some of my unhappy experiences in the profession, and a student

raised his hand and said, “May I ask, Mr. Muczynski, why people like

you bother?” [Laughs] Ugh, you know! The only answer

I came up with was, “Because there has to be more to life than eating,

sleeping, and going to the bathroom.” [Both laugh] These

are very difficult questions to answer. Great thinkers of the

world have written books about it, and philosophize, and come up with

their views and speculations. I don’t know if there are any

absolute answers in this.

BD: Are your

answers to these questions in your music?

RM: If there

are answers, I prefer my music to speak for myself. I feel this

is me. This is as close to me as I can give you folks in

sound. I have to dig within myself, and if you’re interested in

me, then I would like to share this with you, and I hope you get it.

BD: Do most

audiences get it?

RM: I’ve been

pretty lucky with audiences.

BD: What do

you expect of an audience that comes to hear a new piece of yours?

RM: I hope

they won’t leave the hall. [Laughs] No, I don’t have any

trouble like that. I don’t think I expect anything, really.

If I do expect anything, they are just basic things such as their

concentration, their attention and that sort of thing; not to come with

any prejudices, not to come thinking that it’s going to sound like

Tchaikovsky or Sweet Lemonade music. I am really a lyricist in

many ways, but then there certain angry pieces or movements that occur

as well. I’m a rather laid-back, maybe gentle person, but then I

have rages, too, and all of these things that I am must, I suppose,

ultimately find their way into my music.

BD: So much

of your work requires you to be in isolation. Is it almost an

invasion of your privacy, then, when you have a performance with a

public there?

RM: No.

It’s very difficult, though. Today everyone wants you to speak

about your music. I’m sorry to tell you that, but if a composer

is invited to have his music played at a university or a college,

invariably they want you to speak about it, to verbalize. I don’t

mean that I hate doing that, it’s just that sometimes it’s almost

impossible because you might be speaking about a piece you wrote

twenty-five years ago. It’s very difficult to recover, to

remember or retrace your footsteps in that piece. Whereas with a

piece you did last year or five years ago, it’s not so hard.

BD: Are you

ever surprised by what you sounded like, twenty-five or thirty years

ago?

RM: The

music? Not really. There were some student pieces I would

rather have forgotten about entirely. I would like to think that

there is a certain progress. I don’t want to do the same piece

twice. I always hope with each piece I undertake that it be

something different or new. That’s why composers who are very,

very prolific, who write so much — ten

symphonies and fifty sonatas and so forth — you’re almost bound to

repeat yourself a great deal. But if you’re less prolific?

I’m not eager to fill up the world with more symphonies and

concertos. With my concertos and symphonies I would like to write

the best music I can, and to take my time writing that music so that I

won’t be ashamed of it twenty years from now if I’m still around.

BD: You

expect it to last, then?

RM:

Expect? I don’t think one can expect anything.

BD: You hope

that it will last?

RM: Well,

sure, I hope it will last. I know I won’t last, so I hope it will

last.

*

* *

* *

BD: You

mentioned that one of the pieces was something you wrote for the

recording. Did that influence it at all, or was it just another

piece that you knew happened to go on the recording first?

RM: It was a

happy circumstance. You’re talking about the Serenade for Summer. It’s

just the type of piece I wanted to write for small orchestra. By

the way, when I called it Serenade

for Summer, a friend of mine said, “Oh, Delius!” [Both

laugh] I said, “Look, Delius didn’t have a monopoly on summer,

and it’s not a Delius piece.” But it is,

however, kind of a smoky reflection. It might be my Chicago youth

in that piece, somehow. It’s just one movement, about seven and a

half minutes, slow, sustained. It was the type of piece that I

wanted to do. I’m so used to doing pieces with contrast

— either have the slow then going to the fast, or else vice

versa — that in this case I just wanted to do it

as a single slow movement. It could have been, perhaps the

central movement of a three-movement piece. It could be used that

way, in fact.

BD: Are you

ever going to write the outer movements?

RM: No, not

for that. I just said what I had to say in that piece.

BD: Would it

please you if you went to a performance of this, and someone in the

audience would say, “Ah, Muczynski!”?

RM: Oh,

yes! Well, that’s very funny. I realize there are lots of

people who have not heard of me or heard my music. But at the

same time, it’s been my experience to learn of other composers — for

example, Arnold Bax. That is a composer whose works came to me

late in my life. I’ve just been enjoying his symphonies so much

in the last five or six years. Those works are not played much at

all in this country, and until recently they were not too easily

available in record stores. Now they’re coming out in new

recordings on British labels, and they’re very popular.

BD: We’ve

played quite a number of them on the station, and had good response.

RM: I’m very

fond of his work. I like quite a few of the British

composers. [Wistfully thinking about his own works] I had

two big bags full of reviews and programs. I was kind of sloppy

about maintaining a scrapbook because it’s very tedious and boring

after a while. So I got into the habit of having two big bags in

my clothes closet, and throwing my clippings in them. Finally, a

couple of years ago, I was reminded that these bags were filled up

already, and that I was going to have to make a decision as to what to

do with them. I said to a friend, “I’ve either got to burn them

all, or else save them all and put them in a book.” I was

persuaded to save them. But it was very painful in some cases,

not because the reviews were bad, but sometimes the realization that

what you thought happened five years ago was more like fifteen years

ago. [Laughs] Time is moving forward and there’s work to be

done.

BD: Are most

of the pieces you write now on commission, or are they just things you

have to write?

RM: When one

is unknown, as I was in my twenties, and you have nothing on the

boards, nothing published, nothing recorded, then no one’s going to ask

you for a piece. After you have been around for some time and

your works have circulated and seem to be thought well of and are

performed and recorded, then one seems to develop or acquire a

name. It is then people start asking for pieces, or commissioning

you to write pieces. So in the last fifteen years especially,

I’ve been doing more and more commissions, but it’s not my most

favorite way of writing. I enjoyed it the most was when I was

very young. I enjoyed being unknown. I sat down and I

thought, “Well Bob, what shall we write now?”

I commissioned myself.

BD: When you

get a commission now, how do you decide if you’ll accept it or turn it

down?

RM: I’m very

wary these days. I’ve been burned a number of times in a number

of ways. I will not take on a commission now if somebody says, “I

want it by five p.m. on May 22nd of 1988,” or that sort of thing.

I just don’t want that kind of stress.

BD: Even if

what they’re saying is, “We have a performance set up for that day and

we’d like it for that performance”?

RM: I don’t

care! [Laughs] That’s their problem! I want the piece

to be as strong as I can make it, and it seems to be ridiculous to push

that through a sieve just to get it on the boards.

BD: So

someone should commission you and say, “We would like it when it is

finished.”

RM: Yes, and

most of the people are very gracious about it. When Mitchell

Lurie commissioned the work for clarinet and piano, I wrote him and

said, “It’ll probably take me some time.” He said, “I don’t care

how long it takes.” When I had three of the four movements, and

he had already waited quite a long time for that piece, I wrote again

to say, “I’m sorry to tell you, but I feel it needs another movement to

balance the piece out.” He said, “Whenever you feel the piece is

finished, then it’s finished.” That’s the way I like to

work. So, it’s not a question of trying to be difficult or

temperamental. It’s wanting to be reasonably proud of this piece

when it’s done. It is on that record [see photo below], and I was at the

Kennedy Center for Performing Arts in Washington, DC last week when it

was done again.

BD: Are you

ever surprised to find that your piece is being done here or there or

someplace else?

RM: It’s

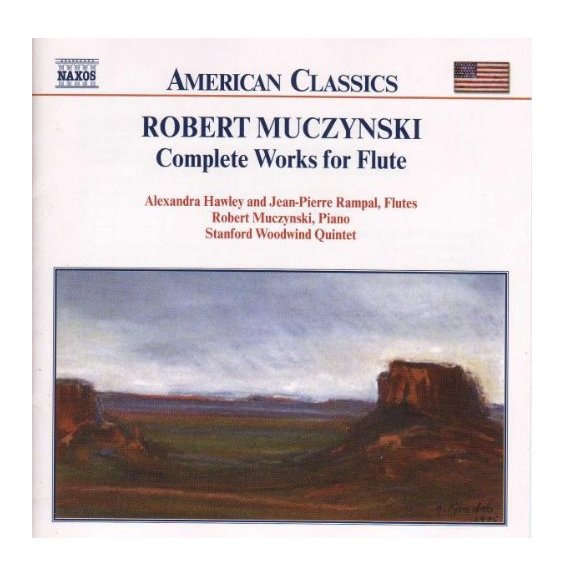

funny you mention that! No. You know what is very

strange? The Sonata for Flute

and Piano was written in Oakland, California, in 1960 and

finished in ’61. Now certainly when I was writing that piece so

many years ago I certainly never had a notion, or had it in my mind

that it would become a standard. First of all, I had no idea

whether it would ever take off, whether it would be published, whether

performers would want to play it. I just wanted to write that

piece. But the thing that fascinates me is that over the years,

once it is released and when it does catch on, when it does seem to be

wanted or needed that the piece is suddenly here and it’s there.

Suddenly it’s all over the place, even in Europe. That fascinates

me. Another thing that fascinates me is like when a friend of

mine in Tucson said to me, “Has it ever occurred to you that there are

people walking the streets in various parts of the country who are

carrying your music around in their heads, or performers carrying your

music around?” That seemed very spooky, almost, to me! It’s

as though they’re walking with part of me in them.

*

* *

* *

BD: Are you

constantly working on pieces? When you put the double bar line

down, do you go immediately on to the next?

RM: Oh, no.

I’m not a faucet, but there was a period in the sixties when I was

writing quite a bit. My publisher in New York was a German

director of this publishing house and he said, “Ach, my God, you’re

like a rabbit!” But I don’t want to be a rabbit. I’ve taken

on some very difficult kinds of pieces to write, certain kinds of

repertory. Especially in this country people do not like piano

trios. There are not too many piano trios or clarinet trios —

that’s clarinet, cello, and piano. There just aren’t too many of

those. There are certain kinds of chamber music that seem to be

more rare. I’ve written a great deal of solo piano music and I’ve

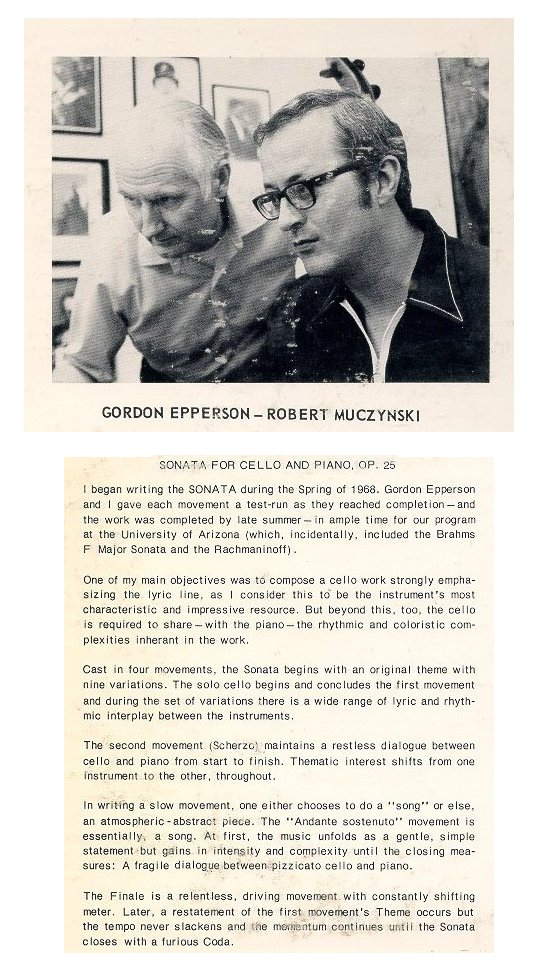

written a great deal of chamber music. I have three piano

sonatas, the Sonata for Cello and

Piano, Sonata for Flute and

Piano, Sonata for Alto

Saxophone and Piano, Italian

Pieces for Clarinet and Piano, and so forth.

RM: Oh, no.

I’m not a faucet, but there was a period in the sixties when I was

writing quite a bit. My publisher in New York was a German

director of this publishing house and he said, “Ach, my God, you’re

like a rabbit!” But I don’t want to be a rabbit. I’ve taken

on some very difficult kinds of pieces to write, certain kinds of

repertory. Especially in this country people do not like piano

trios. There are not too many piano trios or clarinet trios —

that’s clarinet, cello, and piano. There just aren’t too many of

those. There are certain kinds of chamber music that seem to be

more rare. I’ve written a great deal of solo piano music and I’ve

written a great deal of chamber music. I have three piano

sonatas, the Sonata for Cello and

Piano, Sonata for Flute and

Piano, Sonata for Alto

Saxophone and Piano, Italian

Pieces for Clarinet and Piano, and so forth.

BD: Any vocal

music at all?

RM: No, just

some choral music. I’ve written some orchestral music, but

orchestral performances are very difficult to get. These days we

don’t seem to have a conductor would champion a particular composer’s

music such as Kousssevitzky or Stokowksi. At least I don’t see it.

BD: There are

only a few conductors these days that really do anything with

contemporary music — Leonard Slatkin and Michael

Tilson Thomas and Dennis Russell Davies come to my mind. [See my Interviews with

Leonard Slatkin, my Interview

with Michael

Tilson Thomas, and my Interviews with Dennis

Russell Davies.]

RM: I don’t

bump into these people. I don’t see them in the lobby of hotels

and I don’t have my score readily handy under my arm. But

mentioning Stokowski, when I was twenty-four years old I had the

temerity to sit down and write a First

Symphony, thinking I should do that. I never did hear that

piece, but a year or two later I was in New York and I had somehow

gotten the telephone number of Mr. Stokowski at his hotel. I

gulped hard, dialed the number, and I thought that a secretary would

answer. I heard, “Hello?” I recognized his voice, because I

had seen Fantasia!

[Both laugh] I said, “Is Mr. Stokowski there?” He said,

“Speaking,” so we talked a little bit. He said, “Are you a

composer?” I said, “I’m afraid so.” He said, “Don’t be

afraid. Bach was a composer and he was never afraid. What

kind of piece is it?” I said, “It’s a symphony,” and immediately

he said, “What else do you have?” I don’t know if symphonies were

not in or if he preferred program music, or what.

BD: Maybe he

was looking to see what else you had done, to see what other experience

you had.

RM: Well of

course I was so green, and so young.

BD: Did he

look at it?

RM: Yes, and

then he wrote me that he’d made permanent notes about this for future

performance consideration. But as I look back, it was a rejection!

BD: Is this

something you encourage young composers to do — seek

out conductors and hand them their scores?

RM: I have no

advice on that. I just don’t know.

BD: Do you

think idea of having a composer-in-residence for a symphony is a good

idea?

RM: There’s

nothing wrong with anything that helps the composer, and

gets the composer’s music to the orchestra and to the audience.

BD: Is having

a composer-in-residence getting more music to the orchestra, or is the

orchestra just shunting off whatever responsibility they have onto this

poor fellow?

RM: I have

not really thought about this, because I’m not one of those composers.

BD: You’re a

composer-in-residence at the University of Arizona?

RM: Yes.

BD: Is that a

good title, or is that just something that they hung on you unwillingly?

RM: It’s just

sort of a label. A label is a label. I am a composer and I

am in residence, so it’s not a false statement. It does seem

silly because you don’t say, “I’m a plumber-in-residence at the

University of Arizona, or in Tucson, Arizona,” or, “I am

grocer-in-residence at Safeway Mart.”

BD:

[Searching for an optimistic way of looking at it] Isn’t it, in a

way, saying that being a composer is sort of a national or even

international thing, and yet you are in residence here for a while so

they have you for while?

RM: Well,

they’ve had me for a while because I’ve been there since ’65. I

will be leaving this May for all sorts of reasons.

BD: What are

you looking forward to the most?

RM:

Freedom. [Laughs] I would like to own my own time.

I’m not ancient, but not everyone lives to be 75 or 80, and at this age

I have to be very realistic about it. I don’t know how my health

is going to hold up. Some of my friends who were my age and

younger are already planted. So who knows? One has to get a

little bit selfish (in a good way) at a certain point in life.

Not that you step on people, but I’ve got a certain limited amount of

time left to do the work I want to do, so let’s do it. And it’s

not just the composing. I want to do other things. I want

to see who else I am. At the completion of every piece I do, I

feel that I’ve learned perhaps a little more about myself. It

would be nice to think that, anyway. Last week, the clarinetist

who played the Time Pieces in

Washington, D.C., Charles Stier, and I were seated in a bar and he

said, “You realize, don’t you, Muczynski, that you and I, people like

us, we are warts in society.” [Laughs] I said, “Well, thank

you very much for that.” He meant that we’re kind of a

rarity. We don’t really fit in with the norm.

BD: Would you

want to be someone who fits into the norm?

RM: No.

I like cooking, for example. I find it a great deal of fun and

relaxation, and a nice adventure especially when I get frustrated and

nothing is bubbling with the music. Then I can do something

bubbling on the stove and take out all my frustrations there. But

when I go to the grocery store, I’m surrounded by all sorts of

people. There are bound to be people who are white-collar workers

who say, “How’s it going at the office?” or factory workers who ask,

“How’s it going?” But I can’t. I’m squeezing the lettuce

and I can’t look left or right and say, “How is your symphony going?”

or, “How is your sonata going? How’s the cantata down

there?” We are in a rare kind of minority group. What’s

hard to swallow sometimes is that we are faced with this thing of

supply and demand. Perhaps we’re a supply that there’s no demand

for, or not enough demand for, unlike the rock scene or the country

scene.

BD: Is that

real demand, or is that just artificially manufactured?

RM: I don’t

know, but when I walk into a record store, I see before me what is the

most needed, and most rewarded! Not rewarding, but rewarded.

BD: Should we

try to make Robert Muczynski a hot commodity?

RM: Oh,

God! Spare me! [Both laugh]

[At that point I thanked him for the

conversation and we enjoyed some of his sister’s homemade cookies.]

=====

===== =====

===== =====

-- -- -- -- -- -- --

===== =====

===== ===== =====

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago in mid-December,

1987. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB in 1989, 1994 and 1999, and on WNUR in 2007. A small

segment was also used aboard United Airlines (and Air Force One) as

part of their in-flight entertainment package during May and June of

1988. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

BD: Are you a better

composer because you are also a performer?

BD: Are you a better

composer because you are also a performer?  RM: There’s no

point in warning students about anything! [Both laugh] I

tell them, “I don’t have the stone tablets, but you’ve come to study

with me and you must trust my judgment. Otherwise, why come to

me? I will just call the shots. I will just tell you from

my own experience. I’ll call it the way I see it or hear it, and

then you can either take it or leave it, whatever I say.”

RM: There’s no

point in warning students about anything! [Both laugh] I

tell them, “I don’t have the stone tablets, but you’ve come to study

with me and you must trust my judgment. Otherwise, why come to

me? I will just call the shots. I will just tell you from

my own experience. I’ll call it the way I see it or hear it, and

then you can either take it or leave it, whatever I say.” RM: It’s very hard

work. Certain kinds of pieces are fun. I’ve written many

collections of short pieces, or miniature pieces, and I like to do

those. It’s the type of writing that Robert Schumann did so much

of. Even his larger-scale pieces give the illusion of being

large-scale pieces structurally; I’m thinking of pieces like Carnaval and Kreisleriana. They’re really

short pieces sewn together. Or Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition where you

have lovely short pieces unfolding. They are very satisfying, and

there’s a great deal of variety and color there. It’s a nice

journey. I like to do that kind of writing, especially after

having worked for nine months on one piece where you have to wait about

eight to nine months before you see the end of the tunnel. You

think, “God, will this piece never come to an

end? Will I never

finish this piece?” In that lecture he gave

here, Copland said,

“For most of us, it’s no big deal to come up with two minutes or three

minutes of new music. But if you’re aiming to write a piece

that’s twenty-five, thirty-five, forty minutes, then you’ve got to know

how to fill up that musical canvas.” Canvas is a good word

because I’m an amateur watercolorist. I know the problem.

When I sit down with paper the size of piece of typewriter paper, I put

my subject in the center. The painting I do is usually very

square, and then I think, well, there it is. I look all around in

the border, and I think I’ve got all this space here. It’s not

filled in. How do I fill that in?

RM: It’s very hard

work. Certain kinds of pieces are fun. I’ve written many

collections of short pieces, or miniature pieces, and I like to do

those. It’s the type of writing that Robert Schumann did so much

of. Even his larger-scale pieces give the illusion of being

large-scale pieces structurally; I’m thinking of pieces like Carnaval and Kreisleriana. They’re really

short pieces sewn together. Or Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition where you

have lovely short pieces unfolding. They are very satisfying, and

there’s a great deal of variety and color there. It’s a nice

journey. I like to do that kind of writing, especially after

having worked for nine months on one piece where you have to wait about

eight to nine months before you see the end of the tunnel. You

think, “God, will this piece never come to an

end? Will I never

finish this piece?” In that lecture he gave

here, Copland said,

“For most of us, it’s no big deal to come up with two minutes or three

minutes of new music. But if you’re aiming to write a piece

that’s twenty-five, thirty-five, forty minutes, then you’ve got to know

how to fill up that musical canvas.” Canvas is a good word

because I’m an amateur watercolorist. I know the problem.

When I sit down with paper the size of piece of typewriter paper, I put

my subject in the center. The painting I do is usually very

square, and then I think, well, there it is. I look all around in

the border, and I think I’ve got all this space here. It’s not

filled in. How do I fill that in? BD: So what, for

you, is the ultimate purpose of music in society?

BD: So what, for

you, is the ultimate purpose of music in society?

RM: Oh, no.

I’m not a faucet, but there was a period in the sixties when I was

writing quite a bit. My publisher in New York was a German

director of this publishing house and he said, “Ach, my God, you’re

like a rabbit!” But I don’t want to be a rabbit. I’ve taken

on some very difficult kinds of pieces to write, certain kinds of

repertory. Especially in this country people do not like piano

trios. There are not too many piano trios or clarinet trios —

that’s clarinet, cello, and piano. There just aren’t too many of

those. There are certain kinds of chamber music that seem to be

more rare. I’ve written a great deal of solo piano music and I’ve

written a great deal of chamber music. I have three piano

sonatas, the Sonata for Cello and

Piano, Sonata for Flute and

Piano, Sonata for Alto

Saxophone and Piano, Italian

Pieces for Clarinet and Piano, and so forth.

RM: Oh, no.

I’m not a faucet, but there was a period in the sixties when I was

writing quite a bit. My publisher in New York was a German

director of this publishing house and he said, “Ach, my God, you’re

like a rabbit!” But I don’t want to be a rabbit. I’ve taken

on some very difficult kinds of pieces to write, certain kinds of

repertory. Especially in this country people do not like piano

trios. There are not too many piano trios or clarinet trios —

that’s clarinet, cello, and piano. There just aren’t too many of

those. There are certain kinds of chamber music that seem to be

more rare. I’ve written a great deal of solo piano music and I’ve

written a great deal of chamber music. I have three piano

sonatas, the Sonata for Cello and

Piano, Sonata for Flute and

Piano, Sonata for Alto

Saxophone and Piano, Italian

Pieces for Clarinet and Piano, and so forth.