LS: I

said

that many years ago, and

now I'm changing my mind a great

deal. I'm enjoying the operas that

I do, but it's a very limited repertoire that I will do. I'm not

that interested in resurrecting most of the operas that are

deservedly

forgotten. I'm not interested the majority

of the bel canto operas.

LS: I

said

that many years ago, and

now I'm changing my mind a great

deal. I'm enjoying the operas that

I do, but it's a very limited repertoire that I will do. I'm not

that interested in resurrecting most of the operas that are

deservedly

forgotten. I'm not interested the majority

of the bel canto operas.

LS:

[Emphatically] Yes!

Somebody somewhere has got to believe in a few

composers and play them a lot, if

they're going to survive. Just the same

as it's very important for Americans to understand

what their

musical heritage is. I

don't understand, for instance,

why we're limited to hearing one or two pieces once in awhile by

composers like MacDowell and Piston and Ruggles,

and Sessions,

I guess, to a certain degree. I think we owe it to ourselves to

look back and see what our own musical traditions are. Then we

commission a new

piece to help build on what the past

is, while looking at the past to make

sure that we understand what it is

we're building on.

LS:

[Emphatically] Yes!

Somebody somewhere has got to believe in a few

composers and play them a lot, if

they're going to survive. Just the same

as it's very important for Americans to understand

what their

musical heritage is. I

don't understand, for instance,

why we're limited to hearing one or two pieces once in awhile by

composers like MacDowell and Piston and Ruggles,

and Sessions,

I guess, to a certain degree. I think we owe it to ourselves to

look back and see what our own musical traditions are. Then we

commission a new

piece to help build on what the past

is, while looking at the past to make

sure that we understand what it is

we're building on.

LS: No! I

want people to come to music who really

wanna listen to it, and who want

to get captured in it, not those who are there by chore! Don't

come to music that

I'm involved in unless

you really are interested in it. If

you want to support with your dollars,

that's fine! But if

you're really not interested in

it, just put the dollars there and don't fool us with the pretension

of being an arts lover. And

don't

do it, certainly, just to gain an entrée

into society!

If you don't like it but feel you should be

there, perhaps meet a

friend who does know something about it, and perhaps can guide you

wisely. I

think that may be the biggest problem of

all - people go to things indiscriminately,

without being led gradually into

it. For me, opera comes late because most of the

repertoire I knew as a youngster I deplored! I didn't like it at

all! It's

really been, for me, a very selective process. People

say, "You should listen to this

first, and try to do it in this kind

of order." It was much easier that

way.

LS: No! I

want people to come to music who really

wanna listen to it, and who want

to get captured in it, not those who are there by chore! Don't

come to music that

I'm involved in unless

you really are interested in it. If

you want to support with your dollars,

that's fine! But if

you're really not interested in

it, just put the dollars there and don't fool us with the pretension

of being an arts lover. And

don't

do it, certainly, just to gain an entrée

into society!

If you don't like it but feel you should be

there, perhaps meet a

friend who does know something about it, and perhaps can guide you

wisely. I

think that may be the biggest problem of

all - people go to things indiscriminately,

without being led gradually into

it. For me, opera comes late because most of the

repertoire I knew as a youngster I deplored! I didn't like it at

all! It's

really been, for me, a very selective process. People

say, "You should listen to this

first, and try to do it in this kind

of order." It was much easier that

way.

LS: Not so

dissimilar.

Not

really. Leaving aside the text, Salome

is essentially the conflict

between music which is to be in waltz rhythm, and

music which is not to be in waltz rhythm.

It's significant,

for instance, that in all the music of

Jochanaan - of all of it - there is not

one bar in 3/4 time.

It's like it's

the forbidden rhythm, the

waltz. So, in effect,

both Salome and Elektra are the two great examples

of the operatic

tone

poem.

LS: Not so

dissimilar.

Not

really. Leaving aside the text, Salome

is essentially the conflict

between music which is to be in waltz rhythm, and

music which is not to be in waltz rhythm.

It's significant,

for instance, that in all the music of

Jochanaan - of all of it - there is not

one bar in 3/4 time.

It's like it's

the forbidden rhythm, the

waltz. So, in effect,

both Salome and Elektra are the two great examples

of the operatic

tone

poem. LS:

English.

I

couldn't find a

chorus to learn it in Polish during the amount of time. I

found it very beautiful. I'd always known

Roxana's aria mostly from a

Heifetz transcription,

actually. Then I got

interested and looked at it, and

somebody said, "You know, this is possible for an American

premiere." I

looked

at it and listened to it, and it was really beautiful stuff. It's

a shame it's never been played here, so we did it.

LS:

English.

I

couldn't find a

chorus to learn it in Polish during the amount of time. I

found it very beautiful. I'd always known

Roxana's aria mostly from a

Heifetz transcription,

actually. Then I got

interested and looked at it, and

somebody said, "You know, this is possible for an American

premiere." I

looked

at it and listened to it, and it was really beautiful stuff. It's

a shame it's never been played here, so we did it. LS: Oh,

no, he didn't encourage me or

my brother to be a musician. We were, in fact, told to get out

of it because it was too

difficult, too demanding, and ultimately

we'd have to make too many sacrifices. He didn't think, as my

mother didn't, that the

sacrifices were worth it,

if you really weren't going to go at

it wholeheartedly, which my

brother and I then proceeded to do!

LS: Oh,

no, he didn't encourage me or

my brother to be a musician. We were, in fact, told to get out

of it because it was too

difficult, too demanding, and ultimately

we'd have to make too many sacrifices. He didn't think, as my

mother didn't, that the

sacrifices were worth it,

if you really weren't going to go at

it wholeheartedly, which my

brother and I then proceeded to do!

LS:

Orchestral

playing these days is a little more democratic

than it used to be. There was a time when the conductor was the

complete

dictator, virtually having the power and authority to dismiss on the

spot.

If he didn't like what he saw or heard, that player could be relieved

of

the job immediately. These days, that doesn't exist anymore;

there

is much more of a solid base, an orchestral solidarity. The

actual

restrictions against conductors in this country don't condone certain

things

like that. You can be thrown out of the union and you can lose a

job if you get too temperamental.

LS:

Orchestral

playing these days is a little more democratic

than it used to be. There was a time when the conductor was the

complete

dictator, virtually having the power and authority to dismiss on the

spot.

If he didn't like what he saw or heard, that player could be relieved

of

the job immediately. These days, that doesn't exist anymore;

there

is much more of a solid base, an orchestral solidarity. The

actual

restrictions against conductors in this country don't condone certain

things

like that. You can be thrown out of the union and you can lose a

job if you get too temperamental.

* * * * *

LS: I

put into it

what I think is on the page. I don't

try

to inject my own individualities past what I think is the bounds of

good

taste, which is dictated by what's on the page.

LS: I

put into it

what I think is on the page. I don't

try

to inject my own individualities past what I think is the bounds of

good

taste, which is dictated by what's on the page.

* * * * *

LS:

No. The

style and method of which I use the stick in

the hands is about the same. The only difference is that some

orchestras

play what we call on the beat, and some play afterwards. Where

you

give a downbeat, some orchestras are used to just jumping right in on

that

downbeat. As soon as you come down, boom, they play right with

it.

Other orchestras are used playing just a fraction after the beat comes

down. That's the only kind of adjustment I have to make once in a

while.

LS:

No. The

style and method of which I use the stick in

the hands is about the same. The only difference is that some

orchestras

play what we call on the beat, and some play afterwards. Where

you

give a downbeat, some orchestras are used to just jumping right in on

that

downbeat. As soon as you come down, boom, they play right with

it.

Other orchestras are used playing just a fraction after the beat comes

down. That's the only kind of adjustment I have to make once in a

while.

* * * * *

LS: Not much

anymore. When I started out, of course, but

now I'm in a position of being able to pick and choose what I want to

do,

including the soloist and the concerto they'll play. Some people

find that unusual. For instance, I've begun an Elgar cycle for

RCA

in London, and rather than start with one of the more popular works, I

started with an oratorio titled The Kingdom, which is an

extreme

rarity that I find very beautiful. That's some of Elgar's

loveliest

moments; not a great text, but musically quite an extraordinary

work.

I recently recorded the First Symphony for a company called Virgin

Classics

which is just beginning in Europe and will debut in the United States

in

October. I find I like exploring some of the lesser music that I

enjoy, and at the same time recording and presenting some of the more

familiar

works. We have recordings of Brahms that are out. We have

recordings

of Prokofiev; we're recording ballets of Tchaikovsky, we' re recording

works of Schubert. So I'm quite content with the variety that's

on

disc.

LS: Not much

anymore. When I started out, of course, but

now I'm in a position of being able to pick and choose what I want to

do,

including the soloist and the concerto they'll play. Some people

find that unusual. For instance, I've begun an Elgar cycle for

RCA

in London, and rather than start with one of the more popular works, I

started with an oratorio titled The Kingdom, which is an

extreme

rarity that I find very beautiful. That's some of Elgar's

loveliest

moments; not a great text, but musically quite an extraordinary

work.

I recently recorded the First Symphony for a company called Virgin

Classics

which is just beginning in Europe and will debut in the United States

in

October. I find I like exploring some of the lesser music that I

enjoy, and at the same time recording and presenting some of the more

familiar

works. We have recordings of Brahms that are out. We have

recordings

of Prokofiev; we're recording ballets of Tchaikovsky, we' re recording

works of Schubert. So I'm quite content with the variety that's

on

disc.

* * * * *

LS: I play

piano

quite frequently, especially in the summer

festival

in Minneapolis. So I'm still actively involved as a

performer.

I think that a conductor has to continue to keep the hands-on

experience

going. It's really not very difficult just to get up there and

wave

your arms with a stick in it. A baton doesn't make any audible

noise

to the orchestra or the audience, but's a whole different matter when

you

have to put your own hands and fingers down on an instrument and

produce

your own sound. So I try to keep up with that just a bit. I

don't aspire to be a great pianist or a great instrumental performer,

but

I think that the fact that I do sit down and do that once in a while

gives

me a right to be able to converse with other musicians as closer to an

equal than if I did not play any instrument at all.

LS: I play

piano

quite frequently, especially in the summer

festival

in Minneapolis. So I'm still actively involved as a

performer.

I think that a conductor has to continue to keep the hands-on

experience

going. It's really not very difficult just to get up there and

wave

your arms with a stick in it. A baton doesn't make any audible

noise

to the orchestra or the audience, but's a whole different matter when

you

have to put your own hands and fingers down on an instrument and

produce

your own sound. So I try to keep up with that just a bit. I

don't aspire to be a great pianist or a great instrumental performer,

but

I think that the fact that I do sit down and do that once in a while

gives

me a right to be able to converse with other musicians as closer to an

equal than if I did not play any instrument at all.

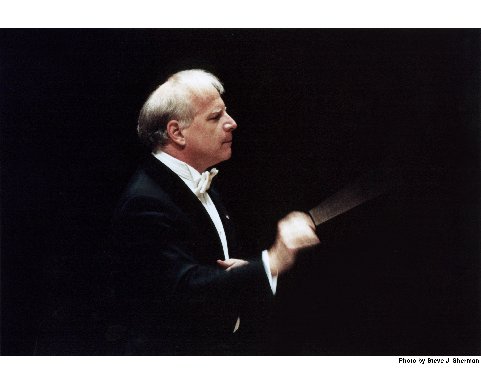

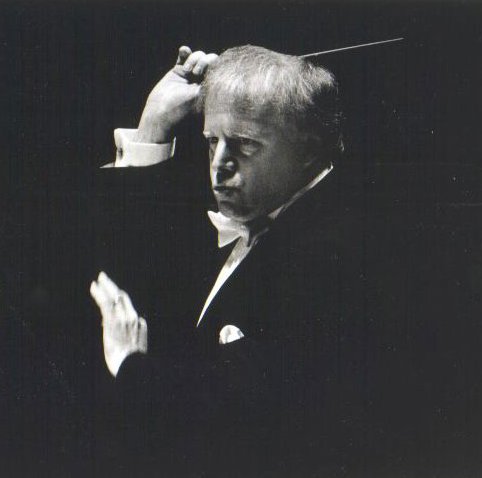

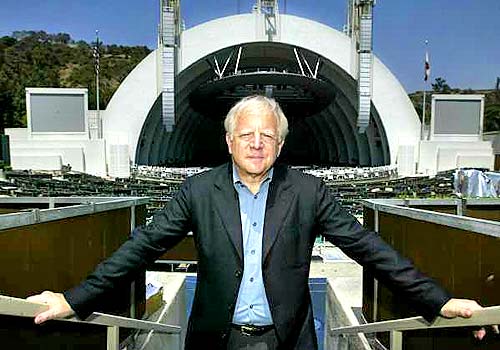

| [From the

program booklet of the

Kennedy Center, February, 2008] Music Director Leonard Slatkin is internationally recognized as a celebrated musician and champion of American music and musicians. Now in his 12th season with the NSO, he is lauded for leading the Orchestra on triumphant tours through Europe, Asia and the US, as well as nationally acclaimed festivals, broadcasts, and recordings. His imaginative programming and interpretations of a vast range of repertoire have been praised and awarded nationally and internationally. Mr. Slatkin and the Orchestra have been celebrated by the White House for their advocacy of America's artistic heritage, and Mr. Slatkin has been recognized with numerous honors and awards, including the National Medal of the Arts and the American Symphony Orchestra League's Gold Baton for service to American music. Mr. Slatkin has regularly appeared over the last two decades with the world's major orchestras and opera companies, including the New York and Berlin Philharmonics, the Chicago Symphony, and Concertgebouw Orchestra, as well as the Metropolitan Opera and Vienna State Opera. Mr. Slatkin is Principal Guest Conductor of London's Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and beginning with the 2008 season, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. At the same time he will become Music Director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. He is Conductor Laureate of the Saint Louis Symphony and the Music Advisor to the Nashville Symphony, and has just completed a very successful three-year term as Principal Guest Conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl. In addition to his conducting appearances, Mr. Slatkin is a frequent host of musical broadcasts, which include the BBC, lending his broad knowledge and expertise. Mr. Slatkin's extensive discography of more than 100 recordings have been recognized with nine Grammy Awards and more than 60 Grammy nominations. Mr. Slatkin is a well-known advocate for arts education in America. He works with students of all ages, both in schools and at the Kennedy Center. This year he begins a relationship with Indiana University as the Arthur R. Metz Foundation Conductor at the Jacobs School of Music, as well as a relationship with American University as its Distinguished Artist in Residence. He holds honorary doctorate degrees from educational institutions such as Juilliard, Washington University, University of Maryland, St. Louis Conservatory, and Shenandoah Conservatory. Mr. Slatkin is the founder and director of the National Conducting Institute, a groundbreaking program established in 2000 to prepare gifted conductors for work with major orchestras. He is an ongoing champion of both old and new music, which has placed him at the forefront of the nation's musical leaders. For more information on Mr. Slatkin, please visit www.leonardslatkin.com. |