By Bruce Duffie

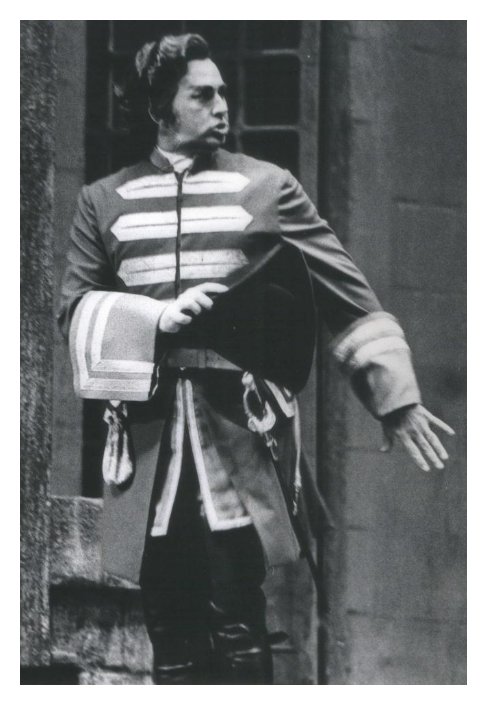

Among his credits are numerous roles in Italian,

German, and American operas, including televised productions on NBC of

Amahl and the Night Visitors,

and a staged performance of Bach’s St.

Matthew’s Passion. “When you stage things for the lens it

can be

a real drama, and a camera can do many wonderful things you never do on

the stage.” When he made this statement, I inquired about using

one of these effects for the Hagen/Alberich scene in Göotterdämmerung,

and Patrick immediately remarked that it would be an incredible project

to do the Ring for TV. “All

the things would actually work!” He

went on to comment that he enjoys seeing pieces of the Ring during a

season, but the more it’s done as a cycle, the more complete experience

you have.

Among his credits are numerous roles in Italian,

German, and American operas, including televised productions on NBC of

Amahl and the Night Visitors,

and a staged performance of Bach’s St.

Matthew’s Passion. “When you stage things for the lens it

can be

a real drama, and a camera can do many wonderful things you never do on

the stage.” When he made this statement, I inquired about using

one of these effects for the Hagen/Alberich scene in Göotterdämmerung,

and Patrick immediately remarked that it would be an incredible project

to do the Ring for TV. “All

the things would actually work!” He

went on to comment that he enjoys seeing pieces of the Ring during a

season, but the more it’s done as a cycle, the more complete experience

you have. BD: Do you work very

hard on your diction, then?

BD: Do you work very

hard on your diction, then? JP: I can still be moved

by a good performance. We’re

super-critical because it’s our business. The audience may notice

the same things, but I understand why. I go with a critical eye,

and if it’s good and performed well, I’m just pulled right into it and

become totally involved. On the other hand, I cannot listen to

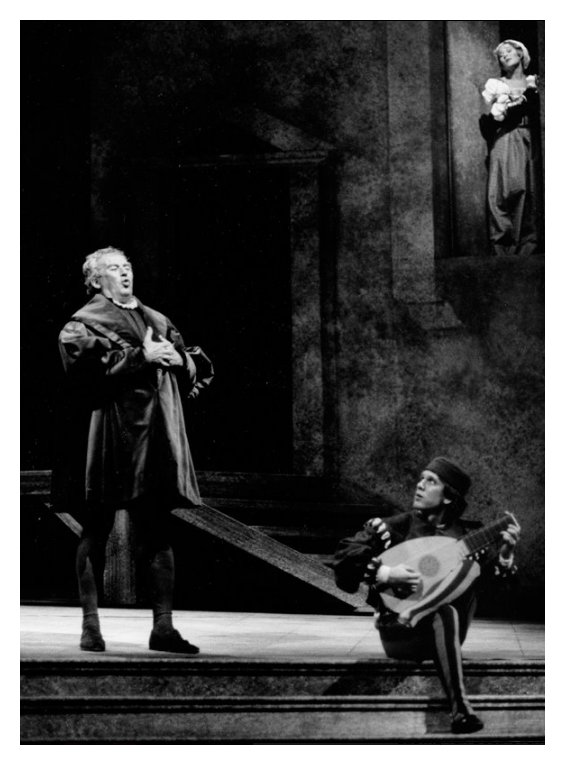

this Meistersinger I’m

doing. Even the parts I’m offstage for, I cannot

listen to or I become too emotionally involved. I think it’s so

gorgeous and I respond to it too greatly. I wouldn’t miss a cue,

but I would be too caught up in it to come out and do what I’m supposed

to do with any credibility. At the end of a performance I’m

always up – if it’s been a good one. The adrenalin is still

flowing and it takes a bit of time before I can go to sleep… I’ve

been seeing this opera for many years and just adore

it. Paul Schoeffler was the Sachs I knew from the beginning, and

I think he was the best one I ever saw. Thomas Stewart is

wonderful, and I think he’s my second favorite, but I’ve never seen him

do it until now when I’m doing it with him.

JP: I can still be moved

by a good performance. We’re

super-critical because it’s our business. The audience may notice

the same things, but I understand why. I go with a critical eye,

and if it’s good and performed well, I’m just pulled right into it and

become totally involved. On the other hand, I cannot listen to

this Meistersinger I’m

doing. Even the parts I’m offstage for, I cannot

listen to or I become too emotionally involved. I think it’s so

gorgeous and I respond to it too greatly. I wouldn’t miss a cue,

but I would be too caught up in it to come out and do what I’m supposed

to do with any credibility. At the end of a performance I’m

always up – if it’s been a good one. The adrenalin is still

flowing and it takes a bit of time before I can go to sleep… I’ve

been seeing this opera for many years and just adore

it. Paul Schoeffler was the Sachs I knew from the beginning, and

I think he was the best one I ever saw. Thomas Stewart is

wonderful, and I think he’s my second favorite, but I’ve never seen him

do it until now when I’m doing it with him. BD: Let’s move over to

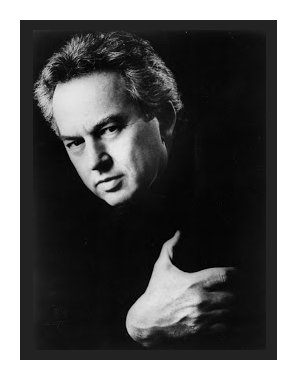

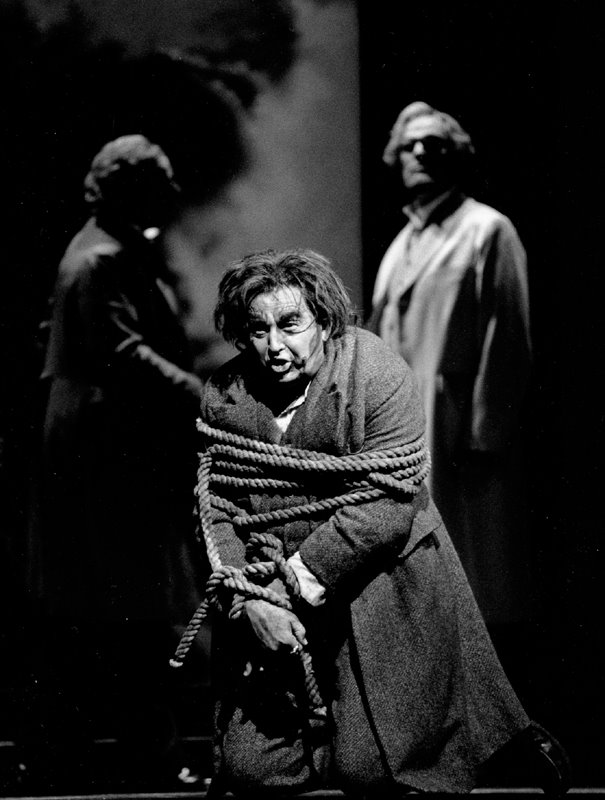

Alberich. [Photo at right in

Seattle production.] Is he likeable at all?

BD: Let’s move over to

Alberich. [Photo at right in

Seattle production.] Is he likeable at all?

Obituary

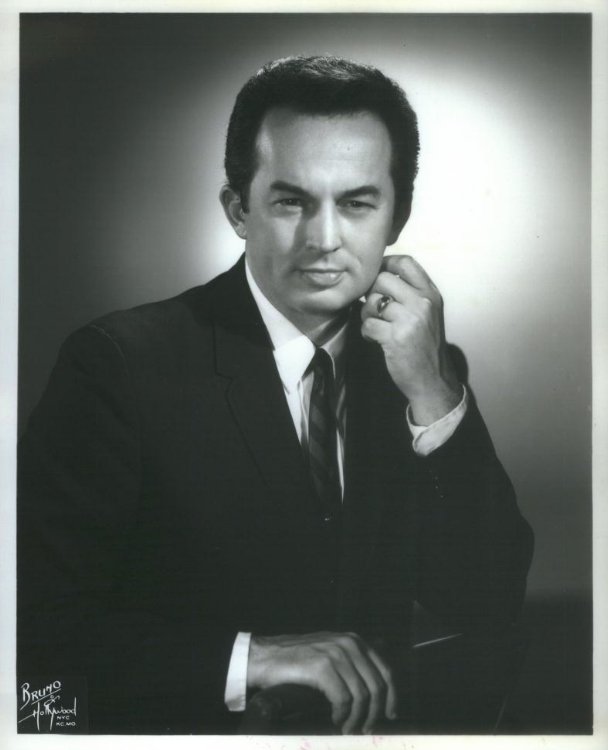

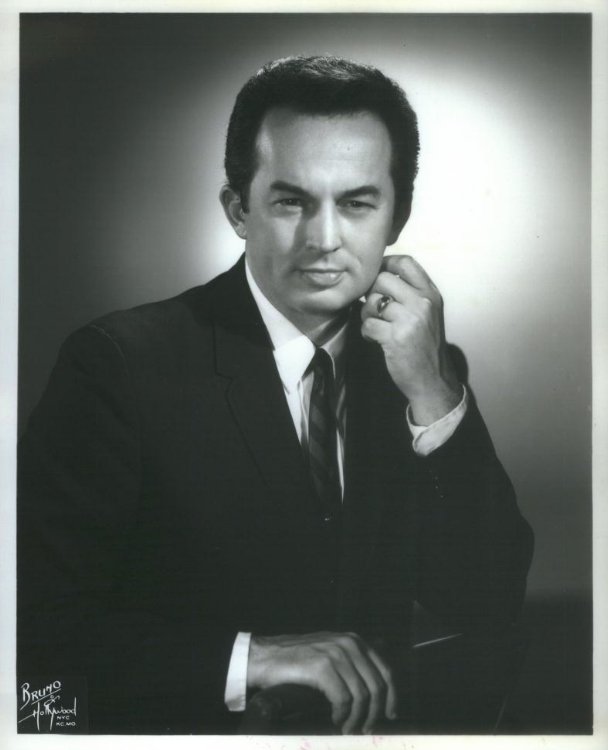

| Julian Patrick, 81, famed baritone

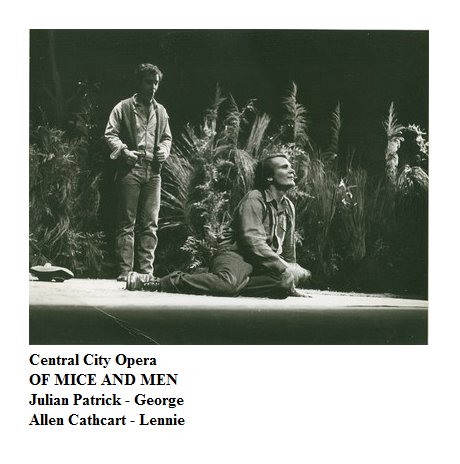

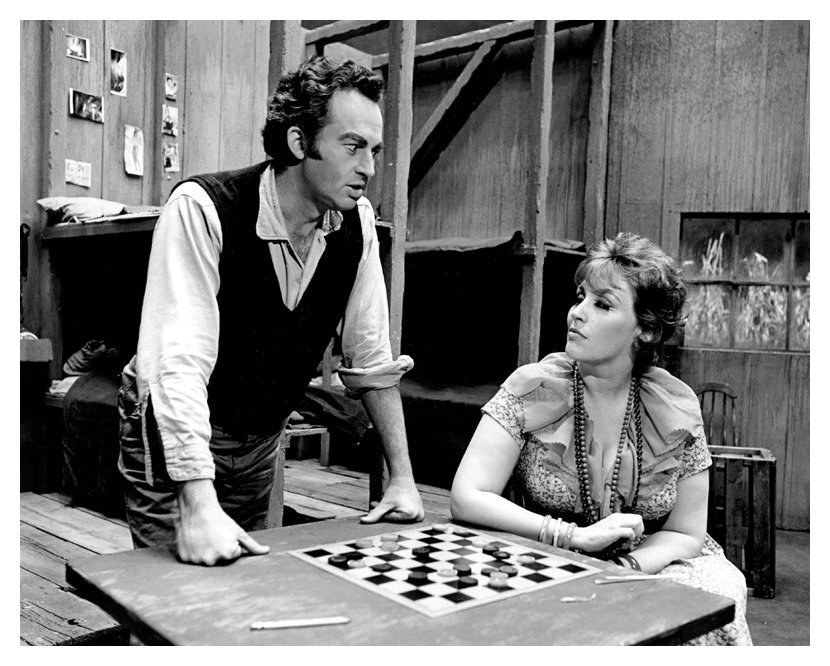

Julian Patrick, a longtime Seattle baritone who was a fixture at Seattle Opera and on the faculty at the University of Washington, died May 8, 2009, in New Mexico. By Melinda Bargreen, Seattle Times staff reporter Julian Patrick, the Seattle-based baritone whose credits extended from Broadway theater to Wagner's "Ring," died in his sleep of natural causes May 8 while on vacation in Santa Fe, N.M. He was 81. A much-revered teacher (he was a University of Washington emeritus professor) as well as a singer of tremendous versatility, Mr. Patrick created the role of George in Carlisle Floyd's opera "Of Mice and Men," [Photo below (added for this website presentation) in Seattle, 1970, with Carol Bayard.] and was in the original casts of the Broadway shows "Once Upon A Mattress," "Bells Are Ringing" and "Fiorello."  Mr. Patrick also performed more than 100 major roles worldwide with significant European and U.S. opera companies; in Seattle, he drew international raves for his Alberich, the central villain of Wagner's "Ring." He performed with Seattle's 5th Avenue Theatre as Benjamin Franklin in "1776," Tony in "The Most Happy Fella" and Judge Turpin in "Sweeney Todd." A true man of the stage, Mr. Patrick created many remarkable performances here in Seattle, as well as at the Metropolitan Opera, Theâtre de Genève, Vienna Volksoper, L'Opéra du Rhin, Marseille Opera, Netherlands Opera, Welsh National Opera, New York City Opera, San Francisco Opera, Chicago Lyric Opera, Houston Grand Opera and Dallas Opera. Even late in life, this born performer loved the stage: He created the acting role of the tormented Gad Beck in the 2007 premiere of "For a Look or a Touch" with Seattle's Music of Remembrance, and later recorded it on the Naxos label. Born in Mississippi in 1927, Mr. Patrick grew up in a music-loving family and joined the Apollo Boys Choir of Birmingham, Ala., beginning a singing career that continued through high school and a stint in the Navy. He went on to the then-Cincinnati Conservatory to study music. Early performances with the impresario Boris Goldovsky led to some operatic appearances, but the young singer's work on a master's degree was interrupted when he was drafted back into military service in 1951 during the Korean War. Based in New York as the singer with the First Army Band, Mr. Patrick found that his uniform got him into Metropolitan Opera standing-room for free. Mr. Patrick later began auditioning for Broadway shows, finding his first success in 1954 with "The Golden Apple" — leading to other opportunities, including operatic ones, touring the country with the Metropolitan Opera National Company for two years. In addition to familiar operatic roles in "La Boheme," "Madame Butterfly" and "The Marriage of Figaro," Mr. Patrick undertook roles in such new works as Douglas Moore's "Carry Nation" and Leonard Bernstein's "Trouble in Tahiti." A creator of roles in many opera and Broadway premieres, Mr. Patrick had strong views on what made new music successful. "If a composer writes something that is melodically and harmonically accessible and is dramatically compelling, it's very likely the critics won't like it," Mr. Patrick told one interviewer. "They are somehow wedded to pieces that are outrageously difficult to play and listen to because they think it is the 'future' of music. I think that the return to melody, however derivative it seems, is most welcome. You may say, 'Oh, it sounds like Puccini.' Well, thank God. That's wonderful. I think that returning to singable lines and to pieces that are dramatically convincing is the right step. There are so many wonderful new pieces now. The greatest of them take compelling stories and set them to music that enhances them and connects to the audience." Mr. Patrick is survived by his life partner for 56 years, Donn Talenti, and also by the Talenti-May family and two cousins, Dr. Bernard Patrick and Ann Nelson Lambright. A memorial service will be scheduled for late June. |

This interview was recorded in his apartment in Chicago on

November 24,

1985. It was transcribed

and published in Wagner News

in July of 1987. It was re-edited, the photos, links and

biography at the end were added, and it was posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.