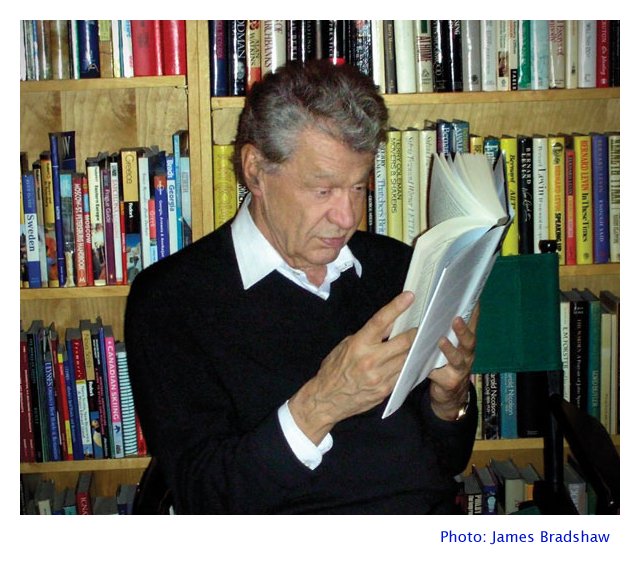

Andrew Porter, born 26 August 1928, in Cape Town, South Africa, is a British music critic, scholar, organist, and opera director. He studied organ at University College, Oxford University, in the late nineteen-forties, then began writing music criticism for various London newspapers, including The Times and The Daily Telegraph. In 1953 he joined The Financial Times, where he served as the lead critic until 1972. Stanley Sadie, in the 2001 edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, wrote that Porter "built up a distinctive tradition of criticism, with longer notices than were customary in British daily papers, based on his elegant, spacious literary style and always informed by a knowledge of music history and the findings of textual scholarship as well as an exceptionally wide range of sympathies." [Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website.]

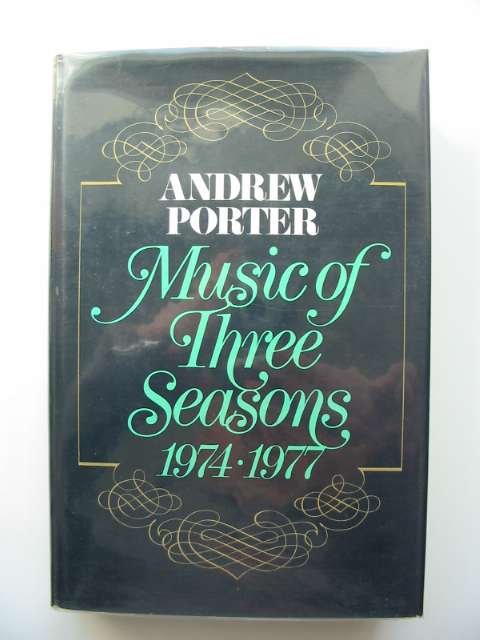

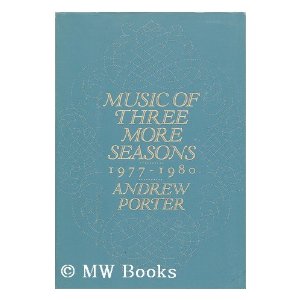

In 1960, Porter became the editor of The Musical Times. From 1972 to 1973 he served a term as the music critic of The New Yorker. He returned in 1974 and remained the magazine's music critic until he moved back to London in 1992. His writings for The New Yorker won respect from leading figures in the musical world. The composer and critic Virgil Thomson, in a 1974 commentary on the state of music criticism, stated, "Nobody reviewing in America has anything like Porter's command of [opera]. Nor has The New Yorker ever before had access through music to so distinguished a mind."

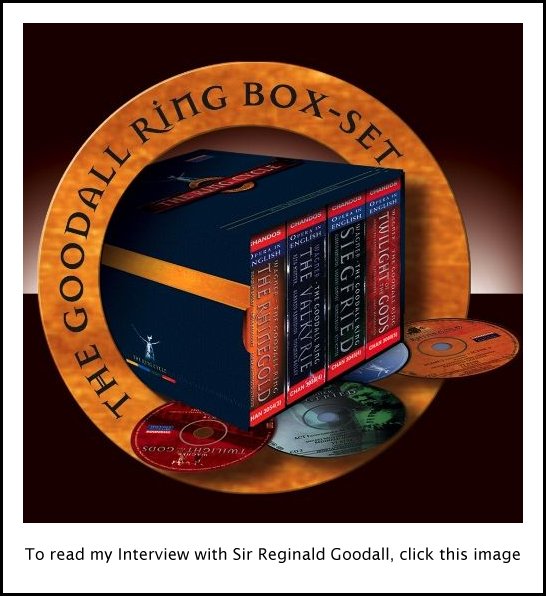

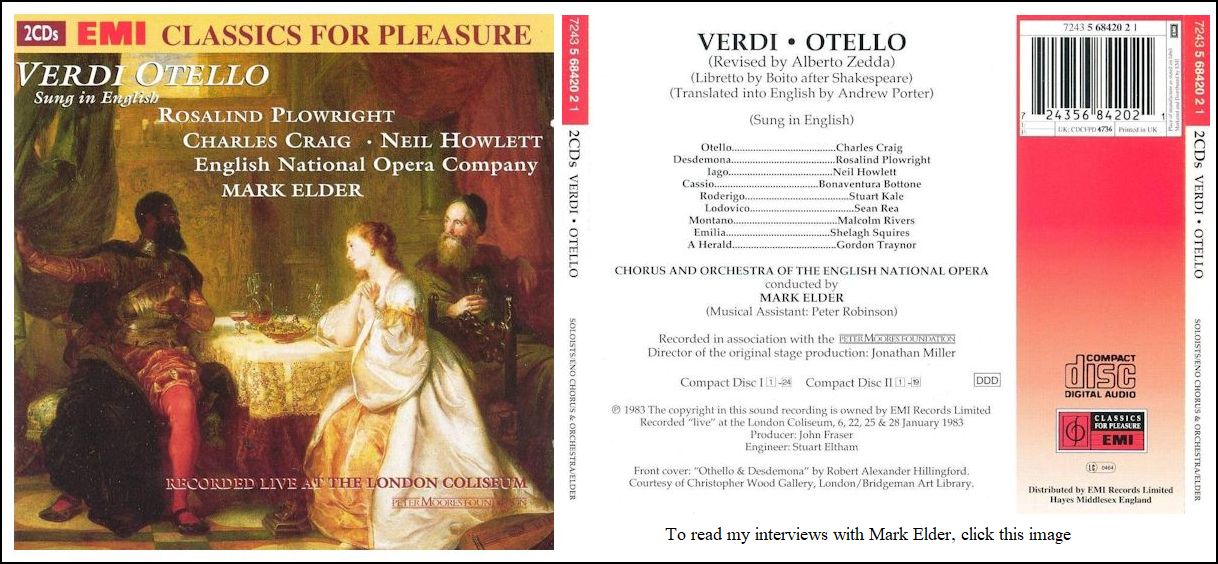

In more recent years he has written for The Observer and The Times Literary Supplement. He has translated 37 operas, of which his English translations of Der Ring des Nibelungen and The Magic Flute have been widely performed. He has also directed several operas for either fully staged or semi-staged performance. He authored the librettos for John Eaton's The Tempest and Bright Sheng's The Song of Majnun.

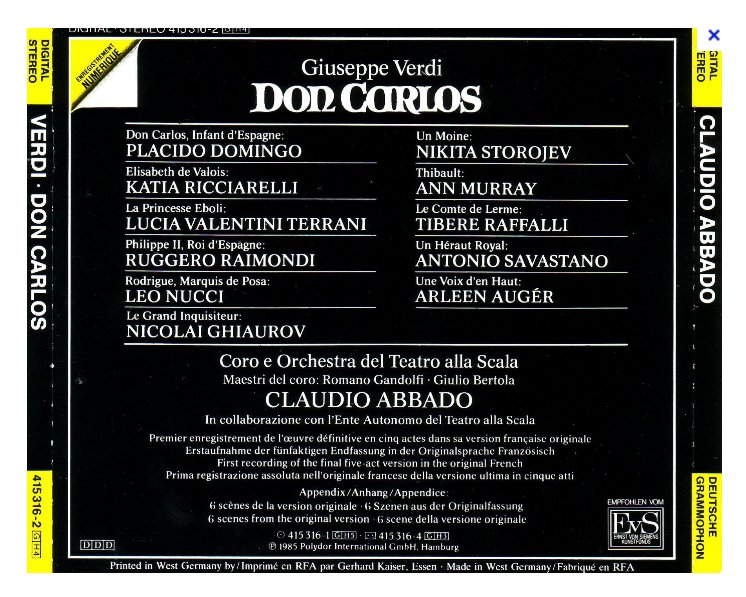

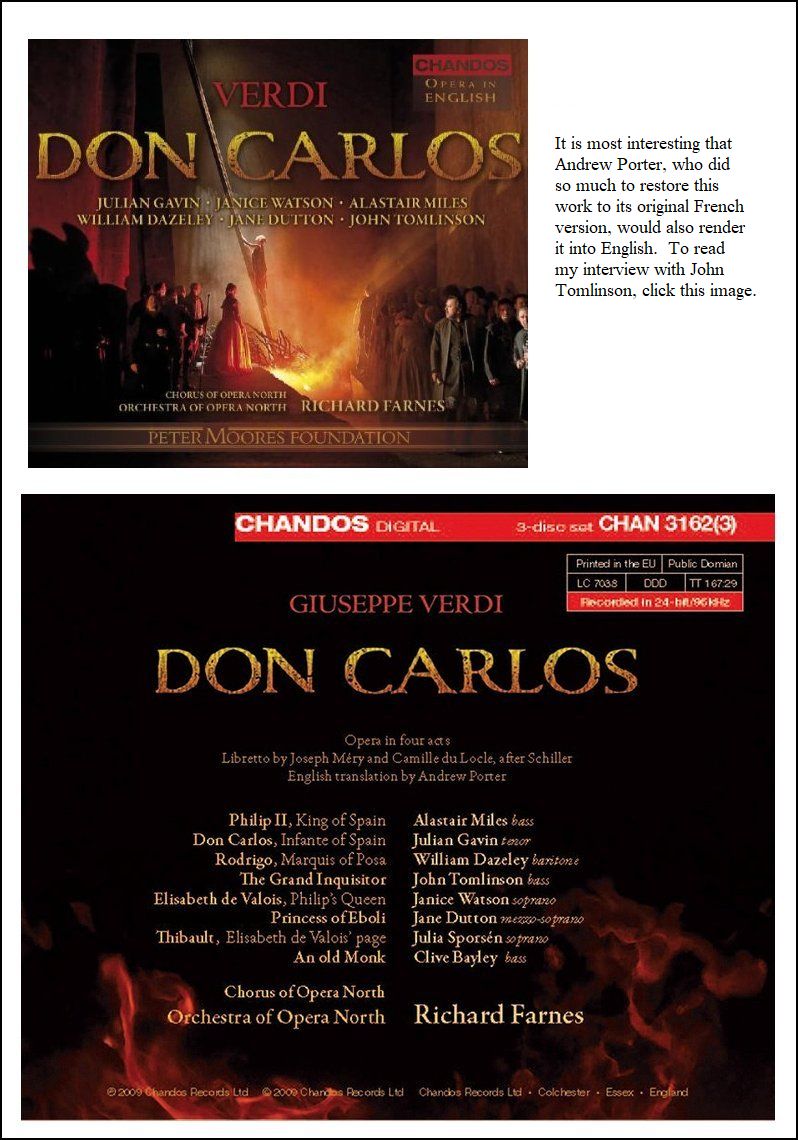

His most significant achievement as a scholar was his discovery of excised portions of Verdi's Don Carlos in the library of the Paris Opera, which led to the restoration of the original version of the work, and the recording shown below. [Jeffrey Tate, who assisted conductor John Matheson when the complete/restored version was first broadcast on the BBC in 1973, speaks of this in his interview.]

In 2003 Porter was honored with the publication of a festschrift, Words on Music: Essays in Honor of Andrew Porter on the Occasion of His 75th Birthday.

[See my Interviews with Lucia Valentini Terrani, Ruggero Raimondi,

Nicolai Ghiaurov, Ann Murray, Arleen Augér, and Claudio Abbado.

The language coach for the recording is Janine Reiss.]

BD

BD BD

BD AP

AP AP

AP

AP

AP AP

AP