A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: Do you always discover new things?

BD: Do you always discover new things? MP: I think music is always singing, whatever it

is. Whether it’s Bach or Beethoven, all the voices are singing.

It’s not only one voice. Of course, one voice is prominent, but all

the voices help sing — the middle voice, the bottom

voice, all of them are joining in, hopefully, singing. That way you

avoid these kind of percussive performances that I think destroy the life

of the music.

MP: I think music is always singing, whatever it

is. Whether it’s Bach or Beethoven, all the voices are singing.

It’s not only one voice. Of course, one voice is prominent, but all

the voices help sing — the middle voice, the bottom

voice, all of them are joining in, hopefully, singing. That way you

avoid these kind of percussive performances that I think destroy the life

of the music. MP: I think there’s an attraction that certain

pieces give you; certain composers, for instance. Last year, or two

years ago, I discovered Handel’s music. I had never heard it in concert;

certainly very few people play the keyboard music. I started by listening

to the oratorios, and then hearing one or two of the operas.

MP: I think there’s an attraction that certain

pieces give you; certain composers, for instance. Last year, or two

years ago, I discovered Handel’s music. I had never heard it in concert;

certainly very few people play the keyboard music. I started by listening

to the oratorios, and then hearing one or two of the operas. MP: I think it’s wonderful, because it’s the personality.

Every voice is different! You would hate for every voice to be the same;

there would be a sort of perfect sound, a glorious sound, but music is more

than this sound. It’s something you express with the soul, so everybody’s

different.

MP: I think it’s wonderful, because it’s the personality.

Every voice is different! You would hate for every voice to be the same;

there would be a sort of perfect sound, a glorious sound, but music is more

than this sound. It’s something you express with the soul, so everybody’s

different. MP: Yes. I learned a lot from that experience.

Going through twenty-seven concertos and seeing his development and evolution

taught me a lot. Still, I feel I’m a beginner in front of Mozart.

[Laughs] So it doesn’t matter! But it has helped, yes.

MP: Yes. I learned a lot from that experience.

Going through twenty-seven concertos and seeing his development and evolution

taught me a lot. Still, I feel I’m a beginner in front of Mozart.

[Laughs] So it doesn’t matter! But it has helped, yes. MP: No, it doesn’t. I, myself, strangely

enough, have rented a harpsichord to study it. I’ve now had it for

about two months. I live in London and was able to get a French harpsichord

to work with the sound. I wanted to explore the emotional possibilities,

not to play it squarely. I’m sure that they didn’t play squarely.

Expressive music has to be expressively played, so they must have played

with rubato and articulation and all kinds of things. So I do experiment

in trying to see what it is that they do. But in the end I have to play

it on the piano, because that’s my instrument, and it’s also the vernacular.

I feel that because it’s the vernacular, certain musical things will be easier

to understand. I might be wrong and I might change my mind, but at

the moment I think that the piano, with its use of dynamics, can bring out

what I want. It’s a regular instrument, not a special world you go

into. That makes it easier to get to grips with the important things

that are going on.

MP: No, it doesn’t. I, myself, strangely

enough, have rented a harpsichord to study it. I’ve now had it for

about two months. I live in London and was able to get a French harpsichord

to work with the sound. I wanted to explore the emotional possibilities,

not to play it squarely. I’m sure that they didn’t play squarely.

Expressive music has to be expressively played, so they must have played

with rubato and articulation and all kinds of things. So I do experiment

in trying to see what it is that they do. But in the end I have to play

it on the piano, because that’s my instrument, and it’s also the vernacular.

I feel that because it’s the vernacular, certain musical things will be easier

to understand. I might be wrong and I might change my mind, but at

the moment I think that the piano, with its use of dynamics, can bring out

what I want. It’s a regular instrument, not a special world you go

into. That makes it easier to get to grips with the important things

that are going on.  BD: Is it frustrating for you, having conducted

these pieces, to work with somebody else conducting?

BD: Is it frustrating for you, having conducted

these pieces, to work with somebody else conducting?|

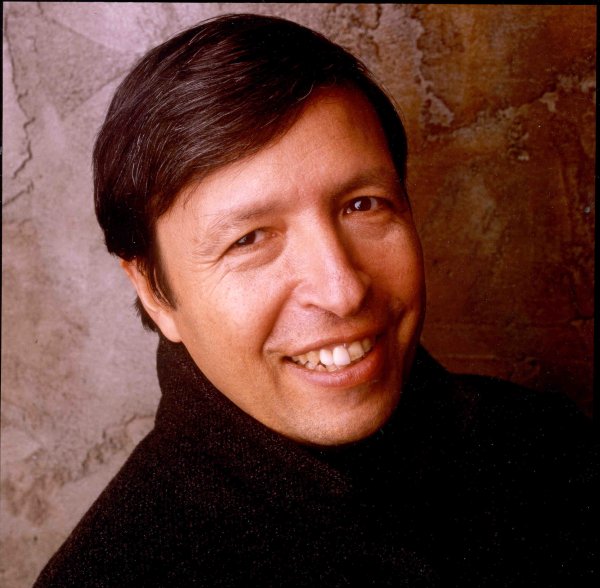

Murray Perahia

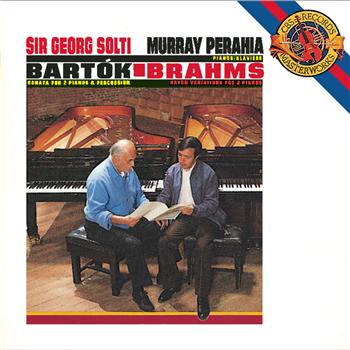

Born: April 19, 1947 - New York City, NY, USA The distinguished American concert pianist and conductor, Murray Perahia, was born of Sephardic Jewish origin, and began playing the piano at four but he didn't start practising seriously until the age of 15. At the age of 17, he attended Mannes College, where he studied keyboard, conducting, and composition with his teacher and mentor Mieczyslaw Horszowski. During the summer, he also attended Marlboro, where he studied with Rudolf Serkin, and Pablo Casals, amongst others. In 1972, he won the 4th Leeds Piano Competition, helping to cement its reputation for advancing the careers of young pianistic talent. Dr. Fanny Waterman recalls anecdotally (in Wendy Thompson's book Piano Competition: The Story of the Leeds) that Mieczyslaw Horszowski had phoned her prior to the competition, announcing that he would enter the winner. Other American contestants had apparently withdrawn their applications upon hearing that Perahia would be competing. In 1973 Murray Perahia worked with Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears at the Aldeburgh Festival. He became co-artistic director in 1981, stepping down in 1989. Perahia famously held a close acquaintance with an elder Vladimir Horowitz, who had a defining influence on his pianism. His first major recording project was the complete piano concertos by W.A. Mozart, conducted from the keyboard with the English Chamber Orchestra. In the 1980's, he also recorded the complete Beethoven piano concertos, with Bernard Haitink and the Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam. In 1992, Murray Perahia's career was threatened by a bone abnormality in one of his hands that had to be operated on. A bone spur on his thumb was causing inflammation, and he had to spend several years away from the keyboard, enduring a series of operations. During that time, he reportedly listened to the music of J.S. Bach. After being given the all-clear, he produced in the late 1990's a series of award-winning recordings of Bach's keyboard works, most notably a cornerstone rendition of the Goldberg Variations (BWV 988). This has caused him to be regarded as a latter-day Bach specialist. He has since made recordings of F. Chopin's etudes, and of F. Schubert's late piano sonatas. He is currently editing a new Urtext edition of Beethoven's piano sonatas. He is regarded as one of the most popular pianists on record today. His recordings are characterized by a consistent quality of sound, technique/interpretation and a careful attention to dynamic and stylistic details. Besides his solo career, Murray Perahia is active in chamber music and appears regularly with the Guarneri and Budapest Quartets. He is also Principal Guest Conductor of the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields orchestra, with which he records and performs. In 1998, Murray Perahia was presented with the 1997 Instrumentalist award by the Royal Philharmonic Society. In 1999, he received an Honorary Doctorate in Music from the University of Leeds. Murray Perahia is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music. On March 8, 2004, Queen Elizabeth II of the UK made him an honorary Knight Commander of the British Empire, in recognition of his outstanding service to music. Other Awards and Recognitions: Claudio Arrau Memorial Medal of The Robert Schumann Society (Awarded in 2000 during the 7th International Schumann Festival); Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance (David Corkhill, Evelyn Glennie, Murray Perahia & Georg Solti for Béla Bartók: Sonata for Two Pianos & Percussion, 1989); Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra) (Andreas Neubronner (producer & engineer) & Murray Perahia for Chopin: Études, Op. 10 & Op. 25, 2003; Murray Perahia for Bach: English Suites Nos. 1, 3 And 6, 1999). |

In the more than 35 years he has

been performing on the concert stage, American pianist Murray Perahia has

become one of the most sought-after and cherished pianists of our time, performing

in all of the major international music centers and with every leading orchestra.

He is the Principal Guest Conductor of the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields,

with whom he has toured as conductor and pianist throughout the United States,

Europe, Japan, and South East Asia.  Born in New York, Mr. Perahia started playing piano at the age of four,

and later attended Mannes College where he majored in conducting and composition.

His summers were spent at the Marlboro Festival, where he collaborated with

such musicians as Rudolf Serkin, Pablo Casals, and the members of the Budapest

String Quartet. He also studied at the time with Mieczyslaw Horszowski. In

subsequent years, he developed a close friendship with Vladimir Horowitz,

whose perspective and personality were an abiding inspiration. In 1972 Mr.

Perahia won the Leeds International Piano Competition, and in 1973 he gave

his first concert at the Aldeburgh Festival, where he worked closely with

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, accompanying the latter in many lieder

recitals. Mr. Perahia was co-artistic director of the Festival from 1981

to 1989.

Born in New York, Mr. Perahia started playing piano at the age of four,

and later attended Mannes College where he majored in conducting and composition.

His summers were spent at the Marlboro Festival, where he collaborated with

such musicians as Rudolf Serkin, Pablo Casals, and the members of the Budapest

String Quartet. He also studied at the time with Mieczyslaw Horszowski. In

subsequent years, he developed a close friendship with Vladimir Horowitz,

whose perspective and personality were an abiding inspiration. In 1972 Mr.

Perahia won the Leeds International Piano Competition, and in 1973 he gave

his first concert at the Aldeburgh Festival, where he worked closely with

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, accompanying the latter in many lieder

recitals. Mr. Perahia was co-artistic director of the Festival from 1981

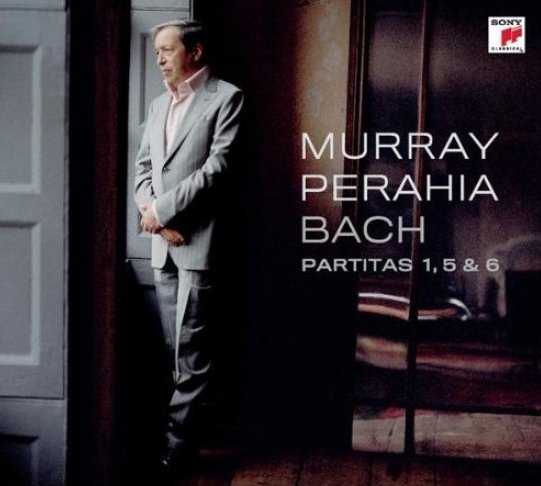

to 1989.During the 2010-11 season, Mr. Perahia performs recitals across North America, including in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston and New York's Carnegie Hall. Recent highlights include a European tour with the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields; concerto appearances with the Israel Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta and with the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich and the Chicago Symphony under the baton of Bernard Haitink; and recital tours across Europe, North America and Asia. Mr. Perahia has a wide and varied discography. In March 2010, Sony Classical released a 5-CD boxed set of his Chopin recordings, including both concerti, the Etudes op. 12 and op. 25, the Ballades, the Préludes op. 28, and various shorter works. Some of his previous solo recordings feature Bach's Partitas Nos. 1, 5, and 6 and Beethoven's Piano Sonatas, opp 14, 26, and 28. He is the recipient of two Grammy awards, for his recordings of Chopin's complete Etudes and Bach's English Suites Nos. 1, 3, and 6, and numerous Grammy nominations. Mr. Perahia has also won several Gramophone Awards. Recently, Mr. Perahia embarked on an ambitious project to edit the complete Beethoven Sonatas for the Henle Urtext Edition. He also produced and edited numerous hours of recordings of recently discovered master classes by the legendary pianist, Alfred Cortot, which resulted in the highly acclaimed Sony CD release, "Alfred Cortot: The Master Classes." Mr. Perahia is an honorary fellow of the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music, and he holds honorary doctorates from Leeds University and Duke University. In 2004, he was awarded an honorary KBE by Her Majesty The Queen, in recognition of his outstanding service to music. |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on March 13, 1997. Portions

(along with recordings) were used on WNIB on December 2, 2000. This

transcription was made and posted on this website late in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.