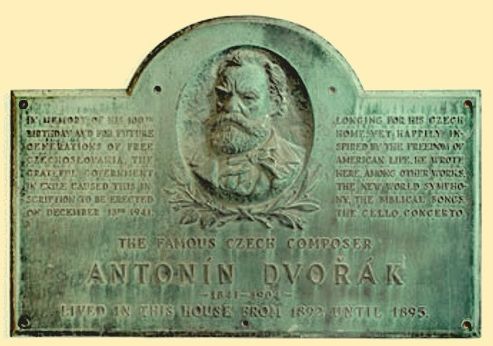

December 13, 1941 – Dedication ceremony at Dvořák House on East 17th Street honors his 100th birthday. Plaque mounting and speeches by Jan Masaryk and Mayor LaGuardia. Pianist Rudolf Firkušný and Metropolitan Opera star Jarmila Novotná perform Biblical Songs, composed in the house. Harry Burleigh and Josef Kovařík, Dvořák's former assistants, attend. |

Fritz Kreisler was there, Bruno Walter was there, Harry

Burleigh, the famous black baritone and composer was there...

Fritz Kreisler was there, Bruno Walter was there, Harry

Burleigh, the famous black baritone and composer was there... SR: The plaque is, I believe, in the

possession of the Czech Ambassador to the United Nations. The Ambassador’s

residence happens to be on Madison Avenue in the 80s in New York.

We do have access to that. Actually, I believe it was my idea...

I don’t want to take the whole credit for this, but I said they

must get this and save it. I believe they also got the mantelpiece

from Dvořák’s fireplace, which still existed, so we do have

that.

SR: The plaque is, I believe, in the

possession of the Czech Ambassador to the United Nations. The Ambassador’s

residence happens to be on Madison Avenue in the 80s in New York.

We do have access to that. Actually, I believe it was my idea...

I don’t want to take the whole credit for this, but I said they

must get this and save it. I believe they also got the mantelpiece

from Dvořák’s fireplace, which still existed, so we do have

that.  SR: Right, my current Messianic calling.

For the first concert I had been in touch with a musician in Europe

because I had found out about the existence of what we believe to be

the original version of Dvořák’s String Serenade.

The work was composed in 1875, however there was a work called Octet

Serenade, which Dvořák wrote in 1873, which is either lost

or destroyed. It is believed to be the original version of the String

Serenade. I had heard about this work a couple of years before

we started the efforts for the statue, and I’d been in touch with English

musicologist Nicholas Ingman. I was trying to find the right situation

and occasion to perform this work, as it had not been performed.

I suddenly got the idea that maybe we could use this as the centerpiece

of a benefit concert to raise money for the statue. Around the same

time, I was in contact with the late great Czech pianist Rudolf Firkušný,

who lived in New York, and he had told us that he would do anything for the

statue. I asked if he would like to play some solo piano music.

There isn’t a great deal of solo piano music by Dvořák, and it’s

not that well known. He said no, he wanted to do the A Major Piano

Quintet with the Guarneri Quartet. I gulped, and asked him if he

would speak to them. He said no, I should call them up. It just

so happens that Arnold Steinhardt, the first violinist in the Guarneri Quartet,

happens to live two blocks from me in New York — which

is not saying anything, because I live on the upper west side of Manhattan

where all the musicians apparently live when they aren’t anywhere else.

So I called Mr. Steinhardt. He’s a wonderful, charming man, as everybody

knows, and he was very enthusiastic about it. So those two pieces

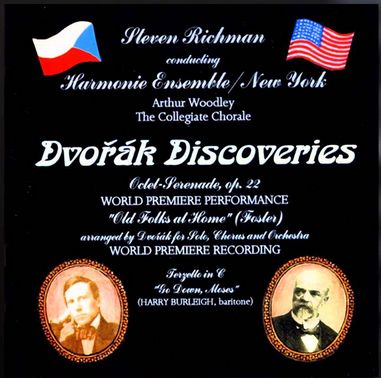

were the beginning of this recording. The Dvořák Discovery

CD actually has the live concert performance of the Octet Serenade.

It does not have the Quintet because it would not fit. It’s

a very long piece. Another work that is on the CD, which is the other

of the major discoveries, is an arrangement that we found that Dvořák

did a month after the premiere of the ‘New World’ Symphony [December

16, 1893]. In 1894 Dvořák conducted a benefit concert

for the New York Herald Clothing Fund. It took place at one

of the old Madison Square Gardens [the second MSG (1890-1925)], which

apparently did have sports, and a concert hall [capacity of 1500],

on an enormous block in the 20s on Madison Avenue. We knew the existence

of this work, but it was actually discovered a couple of years ago in the

Stephen Foster Hall Collection at the University of Pittsburgh. It

is Dvořák’s arrangement of Stephen Foster’s ‘Old Folks at Home’

for one or two solo voices, chorus and orchestra. Dvořák conducted

the premiere of that in late January of 1894, and when we came across this

thing, we decided to do the hundredth anniversary performance with the

great William Warfield

singing it. It was really a successful concert, which, by the way,

was broadcast on National Public Radio. I thought maybe we could use

of the material from that concert for a CD which would be used partially

as to benefit statue. We actually re-recorded the arrangement of Foster’s

‘Old Folks at Home’ later on, but the Octet, certainly

is a live performance.

SR: Right, my current Messianic calling.

For the first concert I had been in touch with a musician in Europe

because I had found out about the existence of what we believe to be

the original version of Dvořák’s String Serenade.

The work was composed in 1875, however there was a work called Octet

Serenade, which Dvořák wrote in 1873, which is either lost

or destroyed. It is believed to be the original version of the String

Serenade. I had heard about this work a couple of years before

we started the efforts for the statue, and I’d been in touch with English

musicologist Nicholas Ingman. I was trying to find the right situation

and occasion to perform this work, as it had not been performed.

I suddenly got the idea that maybe we could use this as the centerpiece

of a benefit concert to raise money for the statue. Around the same

time, I was in contact with the late great Czech pianist Rudolf Firkušný,

who lived in New York, and he had told us that he would do anything for the

statue. I asked if he would like to play some solo piano music.

There isn’t a great deal of solo piano music by Dvořák, and it’s

not that well known. He said no, he wanted to do the A Major Piano

Quintet with the Guarneri Quartet. I gulped, and asked him if he

would speak to them. He said no, I should call them up. It just

so happens that Arnold Steinhardt, the first violinist in the Guarneri Quartet,

happens to live two blocks from me in New York — which

is not saying anything, because I live on the upper west side of Manhattan

where all the musicians apparently live when they aren’t anywhere else.

So I called Mr. Steinhardt. He’s a wonderful, charming man, as everybody

knows, and he was very enthusiastic about it. So those two pieces

were the beginning of this recording. The Dvořák Discovery

CD actually has the live concert performance of the Octet Serenade.

It does not have the Quintet because it would not fit. It’s

a very long piece. Another work that is on the CD, which is the other

of the major discoveries, is an arrangement that we found that Dvořák

did a month after the premiere of the ‘New World’ Symphony [December

16, 1893]. In 1894 Dvořák conducted a benefit concert

for the New York Herald Clothing Fund. It took place at one

of the old Madison Square Gardens [the second MSG (1890-1925)], which

apparently did have sports, and a concert hall [capacity of 1500],

on an enormous block in the 20s on Madison Avenue. We knew the existence

of this work, but it was actually discovered a couple of years ago in the

Stephen Foster Hall Collection at the University of Pittsburgh. It

is Dvořák’s arrangement of Stephen Foster’s ‘Old Folks at Home’

for one or two solo voices, chorus and orchestra. Dvořák conducted

the premiere of that in late January of 1894, and when we came across this

thing, we decided to do the hundredth anniversary performance with the

great William Warfield

singing it. It was really a successful concert, which, by the way,

was broadcast on National Public Radio. I thought maybe we could use

of the material from that concert for a CD which would be used partially

as to benefit statue. We actually re-recorded the arrangement of Foster’s

‘Old Folks at Home’ later on, but the Octet, certainly

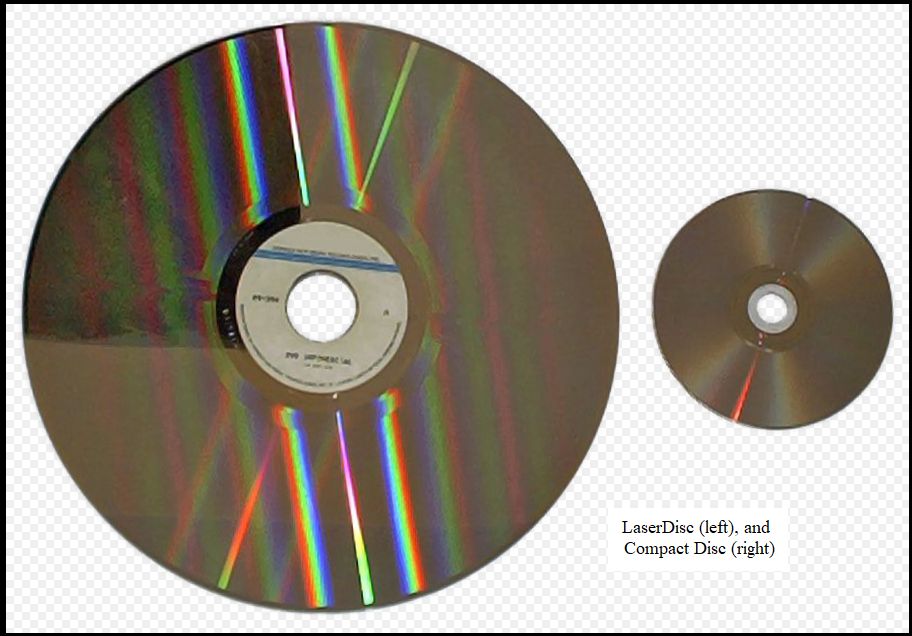

is a live performance. LaserDisc is a home video format, and

the first commercial optical disc storage medium, initially licensed, sold

and marketed as MCA DiscoVision in North America in 1978. Although the

format was capable of offering higher-quality video and audio than its

consumer rivals, VHS and Betamax videotape, LaserDisc never managed to gain

widespread use in North America, largely due to high costs for the players

and video titles themselves, and the inability to record TV programs. It

was not a popular format in Europe and Australia when first released, but

eventually did gain traction in these regions to become popular in the

1990s. By contrast, the format was much more popular in Japan, and in the

more affluent regions of Southeast Asia, such as Hong Kong, Singapore and

Malaysia, and was the prevalent rental video medium in Hong Kong during

the 1990s. Its superior video and audio quality made it a popular choice

among videophiles and film enthusiasts during its lifespan. The technologies

and concepts behind LaserDisc were the foundation for later optical disc

formats including Compact Disc, DVD and Blu-ray.

|

|

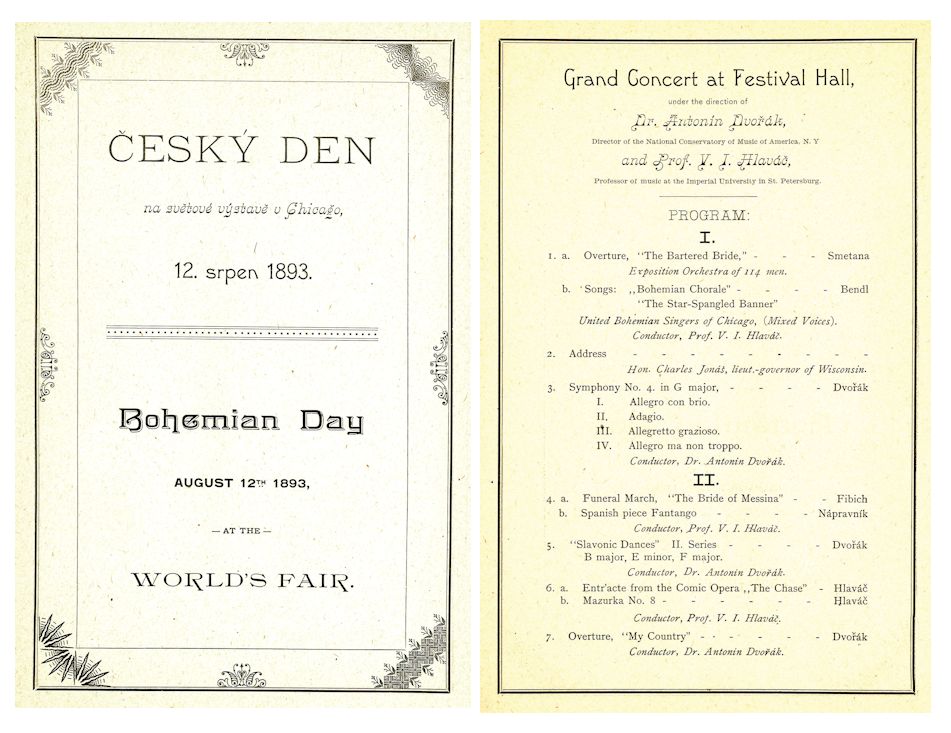

“Bohemia ruled the World’s Columbian Exposition yesterday. It was the special date set apart for that nationality, and its citizens invaded the White City at every entrance by the thousands,” wrote the reviewer in the Chicago Daily Tribune. On August 12, 1893, 8,000 people packed into the fair’s Festival Hall to hear the Exposition Orchestra—the Chicago Orchestra expanded to 114 players—under the batons of Vojtěch I. Hlaváč, professor of music at the Imperial University in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and the director of New York’s National Conservatory of Music in America, Antonín Dvořák. The Tribune reviewer continued: “As Dvořák walked

out upon the stage a storm of applause greeted him. For nearly two minutes

the old composer [age fifty-one!] stood beside the music rack, baton

in hand, bowing his acknowledgements. The players dropped their instruments

to join in the welcome. Symphony no. 4 in G major [now known as no. 8],

considered a severe test of technical writing as well as playing, was

interpreted brilliantly. The Orchestra caught the spirit and magnetism

of the distinguished leader. The audience sat as if spell-bound. Tremendous

outbursts of applause were given.” On the second half of the program, Dvořák

conducted selections from his Slavonic Dances and closed the program with

his overture My Country.

|

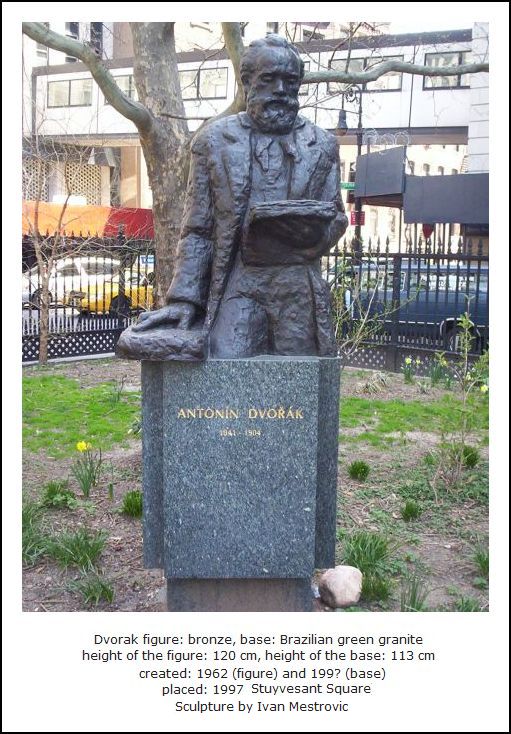

SR: Oh, gosh! I don’t know. I have no answers

to these questions. It’s like when somebody asks me why am I so

interested in putting this statue up, to paraphrase George Mallory, “Because

it ain’t there!” [Laughs] It’s hard to

think about what your interests are. What is my motivation for doing

this? It’s very sad, and it was a travesty that this house was knocked

down. I love Dvořák’s music! It’s very unique; it’s

very warm; it’s very direct. I don’t mean to sound condescending if

I say it’s not complex, but it’s not neurotic the way a lot of other music

is. For lack of a better word, it’s not intellectual. Dvořák

was a great democrat. I’ve been reading his letters, and he was friends

with the caretaker of his estate. He was also friends with Tchaikovsky

and the King of England, but he was friends with very common people.

He saw no divisions between people at all. This is an extremely

bold idea for the time, considering his celebrity. It’s really astounding.

Everything I read about him shows me what a great man he was! The

worst question is who’s your favorite composer? Any musician is

going to say the same thing — the one that I’m working

on at the moment! I become obsessed basically with whoever I’m working

on. I almost become that person. You read everything you can

about him, and get you get totally saturated with him.

SR: Oh, gosh! I don’t know. I have no answers

to these questions. It’s like when somebody asks me why am I so

interested in putting this statue up, to paraphrase George Mallory, “Because

it ain’t there!” [Laughs] It’s hard to

think about what your interests are. What is my motivation for doing

this? It’s very sad, and it was a travesty that this house was knocked

down. I love Dvořák’s music! It’s very unique; it’s

very warm; it’s very direct. I don’t mean to sound condescending if

I say it’s not complex, but it’s not neurotic the way a lot of other music

is. For lack of a better word, it’s not intellectual. Dvořák

was a great democrat. I’ve been reading his letters, and he was friends

with the caretaker of his estate. He was also friends with Tchaikovsky

and the King of England, but he was friends with very common people.

He saw no divisions between people at all. This is an extremely

bold idea for the time, considering his celebrity. It’s really astounding.

Everything I read about him shows me what a great man he was! The

worst question is who’s your favorite composer? Any musician is

going to say the same thing — the one that I’m working

on at the moment! I become obsessed basically with whoever I’m working

on. I almost become that person. You read everything you can

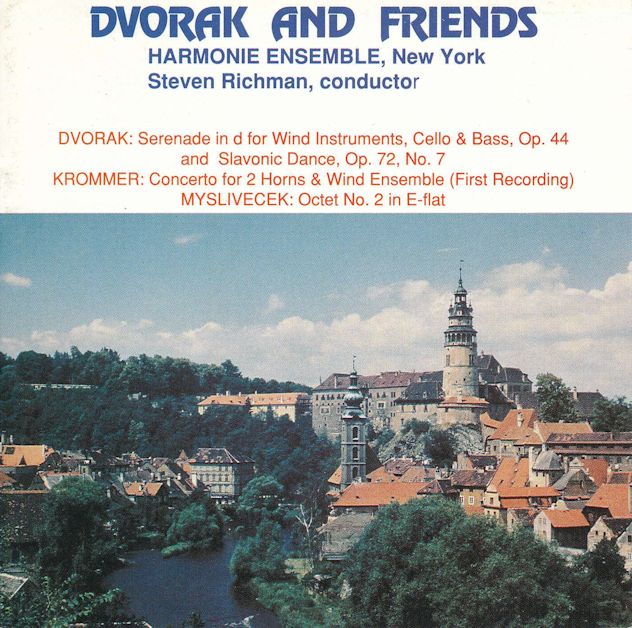

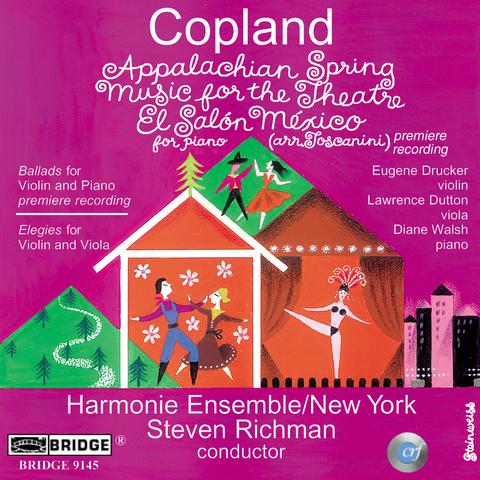

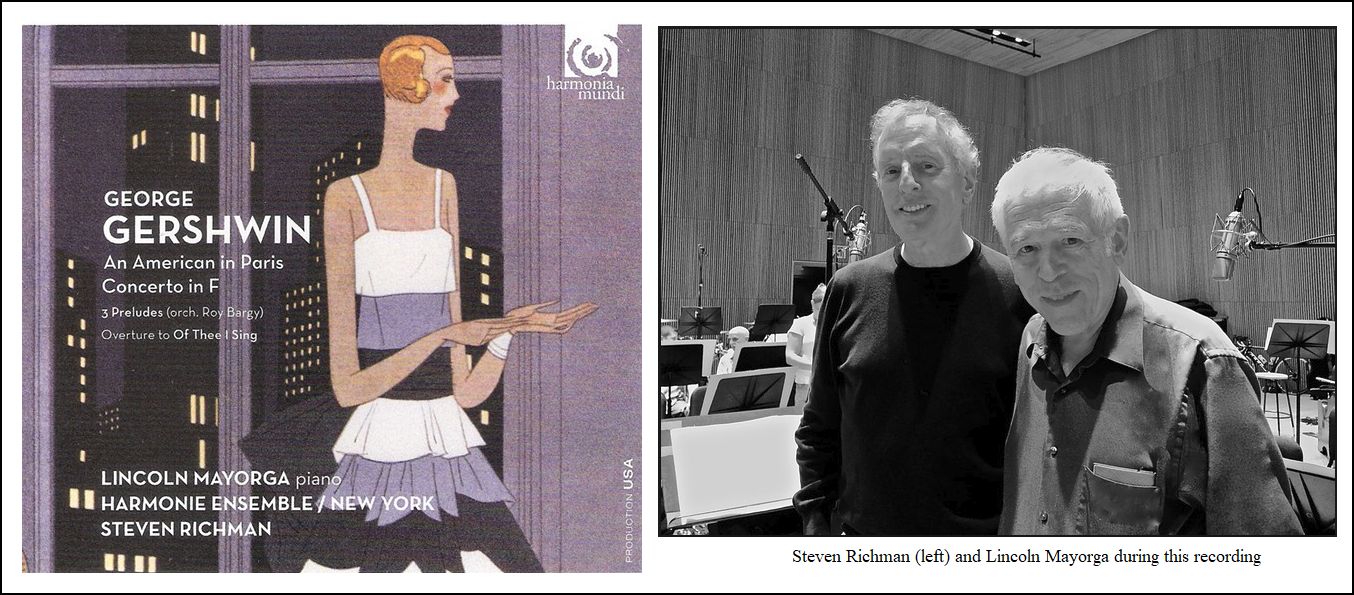

about him, and get you get totally saturated with him. SR: Yes, the Harmonie Ensemble / New York. I founded it

in 1979. Our original core group was a classical wind ensemble

— about a dozen players from Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, the

New York Philharmonic, the New York City Ballet, and a

great pool of freelance players in New York. I just got people together

for a concert in a very old theater that was opened up for concerts in

New York at the time, called Symphony Space, on the opposite side of Manhattan.

I just called up a bunch of my colleagues and said that we’re going to play

the Stravinsky Octet for winds and we’ll do a Dvořák

Wind Serenade. It was January, and in those days January

was a dry month. No longer! Now there’s music 365 days a year,

but in 1979 people had a couple of days off once in a while. So,

we got together and had a few rehearsals. We got a very enthusiastic

response, and started to get some funding, so we immediately begin the orchestral

concerts. One of the things that we did in the second year of our existence

was an eightieth birthday concert for Aaron Copland. Every living American

composer was there! It started at 10 in the morning, and it ended

about half past midnight the next day. There was lots of Copland,

of course, and Copland conducted my orchestra in the chamber version of

Appalachian Spring. I conducted Music for the Theatre,

and it’s been made into two films. There’s a video which has been shown

on PBS in the United States, and on the BBC in England. So we did

a very eclectic mixture of stuff, and that got it lots of birthday concerts

— Stravinsky 100th birthday concert in New York in December

1981, and Leonard Bernstein’s 70th birthday concert at Lincoln Center in

the summer of ’88, at the same time when they were going to the big bash

up at Tanglewood. I did it in New York. He’s from Massachusetts,

but we think of him as in New York boy! So, I just get excited about

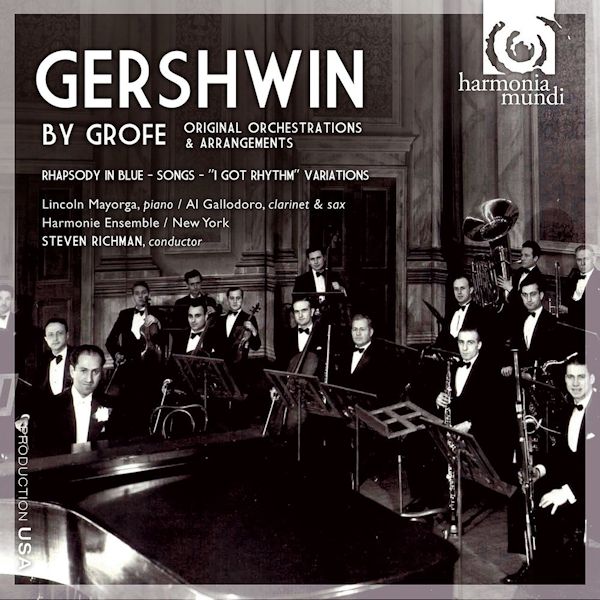

things, and I go for it. That’s why I’m interested in Ferde Grofé

and Stravinsky. I’m actually trying to record a lot of the pieces

we’ve performed. We’ve done a lot of premieres of pieces, even a

couple of small Stravinsky premieres I’m intending to record. My

dream is to record the Gershwin orchestrations. I think that would

be wonderful!

SR: Yes, the Harmonie Ensemble / New York. I founded it

in 1979. Our original core group was a classical wind ensemble

— about a dozen players from Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, the

New York Philharmonic, the New York City Ballet, and a

great pool of freelance players in New York. I just got people together

for a concert in a very old theater that was opened up for concerts in

New York at the time, called Symphony Space, on the opposite side of Manhattan.

I just called up a bunch of my colleagues and said that we’re going to play

the Stravinsky Octet for winds and we’ll do a Dvořák

Wind Serenade. It was January, and in those days January

was a dry month. No longer! Now there’s music 365 days a year,

but in 1979 people had a couple of days off once in a while. So,

we got together and had a few rehearsals. We got a very enthusiastic

response, and started to get some funding, so we immediately begin the orchestral

concerts. One of the things that we did in the second year of our existence

was an eightieth birthday concert for Aaron Copland. Every living American

composer was there! It started at 10 in the morning, and it ended

about half past midnight the next day. There was lots of Copland,

of course, and Copland conducted my orchestra in the chamber version of

Appalachian Spring. I conducted Music for the Theatre,

and it’s been made into two films. There’s a video which has been shown

on PBS in the United States, and on the BBC in England. So we did

a very eclectic mixture of stuff, and that got it lots of birthday concerts

— Stravinsky 100th birthday concert in New York in December

1981, and Leonard Bernstein’s 70th birthday concert at Lincoln Center in

the summer of ’88, at the same time when they were going to the big bash

up at Tanglewood. I did it in New York. He’s from Massachusetts,

but we think of him as in New York boy! So, I just get excited about

things, and I go for it. That’s why I’m interested in Ferde Grofé

and Stravinsky. I’m actually trying to record a lot of the pieces

we’ve performed. We’ve done a lot of premieres of pieces, even a

couple of small Stravinsky premieres I’m intending to record. My

dream is to record the Gershwin orchestrations. I think that would

be wonderful!

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 7, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998; and on WNUR in 2003 and 2014. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.