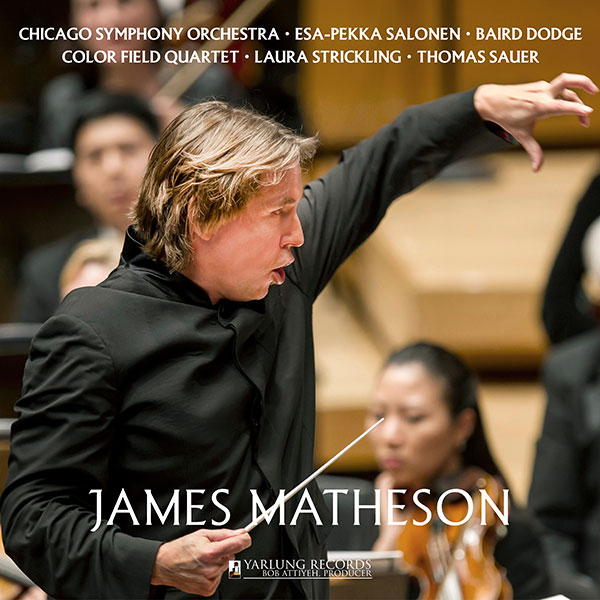

Conductor / Composer Esa - Pekka

Salonen

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

This conversation is from the very beginning of 1988, a year before

Salonen was offered the Guest-Conductorship of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

He had already conducted there, but the twenty-year impact of this

collaboration was still on the horizon.

A multi-faceted musician, his focus is mainly on two overlapping tasks

— conducting and composition. Each

feeds the other, and together they propel his ongoing legacy.

After reading this interview, one comes away feeling that this man

is not only a superb musician, but also a deep thinker who can express those

ideas in a manner that communicates with everyone and anyone.

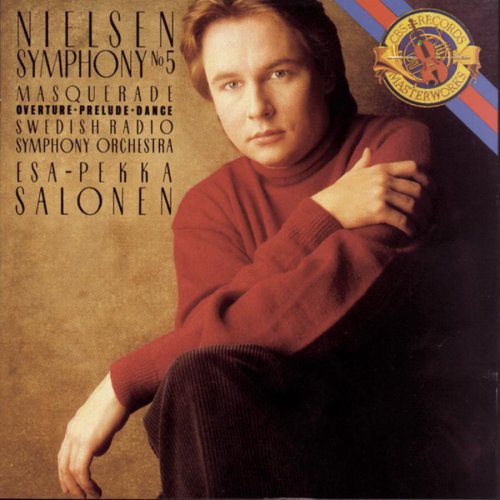

In 1988, Salonen was making his debut with the Chicago Symphony doing

the Nielsen Fourth Symphony. He would return several times

to conduct the Orchestra, and would also bring an all-Scandinavian program

with his Swedish Radio Orchestra just two months after that CSO debut.

Here is what was said that afternoon . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Being Scandinavian, do you feel

a special passion to bring the music from Scandinavia all over the world?

Esa-Pekka Salonen: It’s not the geographical

aspect which is the vital one. For me it’s basically that I want

to conduct music that I like, and which I feel comfortable with.

Nielsen and Sibelius just happen to be those sort of composers.

BD: With this vast repertoire from three centuries

of symphonic music, how do you decide which pieces you will conduct and

which pieces you will set aside?

E-PS: Often it’s a lot of guessing because you

don’t really know whether this piece is good for you or not until you

have conducted it at least once. Sometimes there are pieces which

need fifteen performances so that you really are comfortable with the

music. So when I see score which excites me, then I try to program

it somewhere, and after the first performance I know a lot more about

my relationship to that piece.

BD: There must be some things you look for in the score

to give you a clue that this will excite you or that will not excite

you.

BD: There must be some things you look for in the score

to give you a clue that this will excite you or that will not excite

you.

E-PS: Yes, but there’s no rule really what sort

of things do excite me because a lot of the most exciting things in music

are not really possible to explain in verbal means. So it’s difficult

to describe what is the element that excites you.

BD: Do you find that most of the pieces you are

doing — the pieces that do excite you

— are masterworks?

E-PS: No, not necessarily. There’s also

this curiosity aspect. Sometimes it’s nice to conduct music which

is very seldom played and very seldom heard, and which doesn’t belong to

the most central repertory. Sometimes it’s music which certainly doesn’t

belong to the real list of masterworks, but that serve an important function

as well.

BD: Do you look for a balance in each of your

concerts with a masterwork, and maybe something of lesser importance?

E-PS: Basically I don’t conduct music that I don’t

believe in. So even if the title ‘masterwork’ doesn’t apply, I avoid

conducting music which I think is not over-high in artistic value.

BD: Is the public right when it decides that something

is what they want to hear again and again, or when it’s something they

don’t ever want to hear again?

E-PS: Not always. There are lots of examples

of wrong judgments from both the critics and the audiences during musical

history. If you think about composers such as Mozart, Beethoven,

Bruckner, Mahler, those are people whose greatest works basically gained

that popularity after their death. So the immediate public reaction

is not always something you can rely on.

BD: Do you feel it’s your job to convince the

public about the other works for which you feel passionately?

E-PS: Not necessarily to convince, but my function

partly is to give an alternative, to let the audience have a chance to

get to know some of these works which I believe in and I’m excited about,

and which do not necessarily belong to the central mainstream repertory.

BD: What do you feel is the ultimate purpose of

music in society?

E-PS: [Ponders a moment] I don’t think I’m

able to answer to that question in that form. Music is basically

a biological need in a human being, and as such it doesn’t necessarily

have a purpose in the sense of gaining something because it’s about a biological

phenomenon. In every culture during human history, mankind has had

some sort of musical culture. That tells us about the universal

importance of music, but it doesn’t answer the question of what one possibly

gains by playing or listening to music. So it’s a difficult question.

In our society now, one of the most important functions for classical music

is that it tells us about our connection to the past, and also, in a way,

tells us about our connections with the future. If we have an institution

which is as impractical and as inefficient and as expensive as a symphony

orchestra, the fact that it still exists very intensely and has audiences

that are growing, there has to be an important message somewhere.

One of the most important things is that playing music from the Classical

period, for instance, can show that something that was written two hundred

years ago, or three hundred years ago can still be vital and exciting today.

It tells us that we have our place in the history of this civilization.

So I think that is the primary function of classical music at the

moment.

* * *

* *

BD: Is there any real difference in the music that

comes out of Scandinavia from the music that comes out of Western Europe,

or Eastern Europe or the United States?

E-PS: The most characteristic thing about Scandinavian

music, especially Finnish music, is the fact that it’s culturally between

Western Europe and Eastern Europe. So in Sibelius you can hear

influences from both sides. Finland happens to be in the middle

of the Byzantic and the Catholic culture influence, so it’s basically

a place where East and West meet. That might be a special characteristic

of Scandinavian music. Of course, nowadays the contemporary music

which is composed in Scandinavia has lost its national cultural identity

in the sense that you cannot anymore hear whether these pieces are composed

in Tokyo, or in New York, or in Copenhagen, or in Berlin. The musical

language has become more universal because of the mass-media and the global

communication.

BD: Is it a good thing or a bad thing that we’re

losing this identity?

E-PS: The good thing about it is that the musical communication

beyond the limits of language is easier, so there can be more musical exchange

between different cultures without having big syntax problems. But

also it’s a pity that different countries lose their personal characteristics.

With all these satellite TV channels and videos and things there’s

a danger that our whole culture will become more impersonal and colorless

as a result of all these commercial mass-communication systems.

E-PS: The good thing about it is that the musical communication

beyond the limits of language is easier, so there can be more musical exchange

between different cultures without having big syntax problems. But

also it’s a pity that different countries lose their personal characteristics.

With all these satellite TV channels and videos and things there’s

a danger that our whole culture will become more impersonal and colorless

as a result of all these commercial mass-communication systems.

BD: Do you feel that classical music should not

be marketed the way other kinds of popular media are?

E-PS: I don’t know. Sometimes I feel that

the only chance for classical music to survive is to fight the commercial

music with the same weapons — the same hype, the

same artificial star-cult — but I’m not always sure.

Sometimes I feel that one shouldn’t touch that sort of ideology at all,

and just let classical music be interesting because of its own artistic

value. But it’s difficult to tell. Obviously, mass-media is

the most efficient way to reach people, so why not to use it? [Vis-à-vis

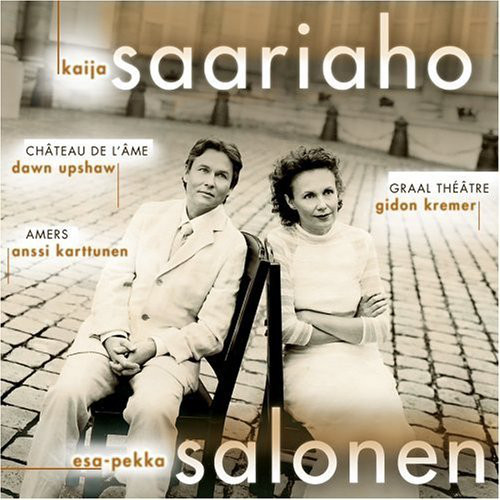

the recording shown at left, see my Interviews with Dawn Upshaw, and Gidon Kremer.]

BD: Then where, for you, is the balance between

the entertainment value and the artistic achievement in classical music?

E-PS: It’s difficult to tell because people have

different reasons why they go to concerts and why they buy records.

But I feel that a contemporary music concert is less entertainment and

more cultural excitement than a popular classical concert with a major

orchestra and a major conductor and a major soloist. But that doesn’t

necessarily mean the artistic value of contemporary music goes this higher,

so an interesting artistic event is a mixture of those two aspects

— provocation and fulfilling of spiritual needs.

BD: Do you feel any special commitment to yourself

towards contemporary music or new works?

E-PS: Yes. Almost fifty per cent of my repertory

is music which has been composed during the last two decades.

BD: Will it continue to be? Are you going

to continue to search out new scores for the rest of your career?

E-PS: Yes. I’m more and more convinced

about the importance of contemporary music, and that’s my number one field

of interest. For me it’s the most natural way to communicate with

my own time, with my own society — to perform works

that have been written recently — which doesn’t

mean that I don’t like and love all these old masterpieces. But somehow,

I feel in the cultural environment, the musical environment, today there’s

no balance between historical music and contemporary music. This

is a well-known fact, of course, but when Brahms was active as a composer,

all the symphony concerts were contemporary music concerts. No

one ever played ‘old music’. It was a really rare event. When

Mendelssohn did his first Bach performances, it was unheard of. Something

happened in the beginning of this [twentieth] century so all the concert

programs became more conservative and conventional. I think it’s

not really a healthy situation. Somewhere there’s this gap between

the audience and the composers, and I don’t really know why it didn’t

exist before and why it exists now.

BD: What advice do you have for composers who

are writing today?

E-PS: [Thinks a moment] Actually I wouldn’t

advise so much composers. I would rather advise orchestras, and

also orchestra managers, and conductors, and critics, and record companies

to help these people who write music today. There’s a lot of good

music being written today all over the world. It doesn’t get enough

publicity, and it doesn’t reach enough audience because of all these conventions

and all these commercial aspects. Actually in composers we have a

potential which we don’t use.

BD: So you’re urging them just simply to write

more?

E-PS: Yes. What I’m saying to composers

is keep on composing. It’s our responsibility as conductors, performers,

musical organizers, and agents and so forth to make this music known.

BD: What advice do you have for the audience

who comes to hear a piece of new music?

E-PS: If they already come to hear a piece of new

music on the program, that audience is already enlightened. So

to those people I have nothing to say, just to congratulate them.

But audiences basically believe what the mass-media says if

it’s written in a convincing way. So it’s

basically that the programs reflect the bad communication between mass-media

and the creative artist today.

* * *

* *

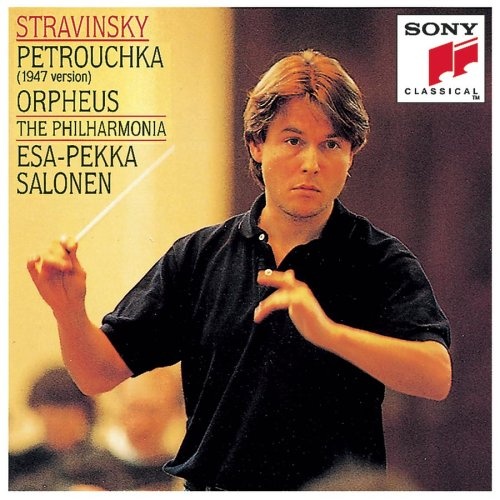

BD: You make quite a lot of recordings. Do

you conduct any differently in the recording studio than you do in the

concert hall?

E-PS: I believe so, yes, because I don’t feel that

a good recording is a substitute for a concert. Ideally a good

recording is something else. It’s a different form of art, and

in this sense Glenn Gould is one of my recording heroes because he had

the courage to use the media in a way which was unheard of before. There

are not that many people who’ve done that sort of thing since, either.

My readings in the recording studios are more analytical, more provocative,

and perhaps a little bit more clinical.

BD: Not enough heart?

E-PS: No, I don’t believe in the polarity of heart and

brain in music. It’s a superficial analysis to divide musical personalities

into two groups — heart and brain — because

it’s too simple to be true. But I feel that the recording should

reveal something of a piece of music which doesn’t necessarily come out

in a concert situation, and ideally it would convey something which offers

a new aspect to that particular work.

E-PS: No, I don’t believe in the polarity of heart and

brain in music. It’s a superficial analysis to divide musical personalities

into two groups — heart and brain — because

it’s too simple to be true. But I feel that the recording should

reveal something of a piece of music which doesn’t necessarily come out

in a concert situation, and ideally it would convey something which offers

a new aspect to that particular work.

BD: Do you ever feel that you’re competing against

your recording when you’re conducting a concert of the same music?

E-PS: Not really because my starting point is

a little bit different when I conduct the concert. In a concert

you also create an atmosphere. It’s a communication situation between

the orchestra and the audience, and between the conductor and the orchestra,

whereas in a recording it’s only a one-way communication. A concert

is a trial drama, so to speak, so it’s entirely different for me.

BD: When you’re preparing a symphony concert,

do you do all the work in rehearsal, or do you leave a little bit for

that spark of inspiration at the actual performance?

E-PS: This depends. Actually I would rather

not leave anything for the concert [bursts out laughing] but as we almost

never get enough rehearsal time in order to really work meticulously on

every possible detail, there’s always something left to the concert as

well. There are always some unsolved moments, and it might be an

advantage sometimes. But sometimes it clearly isn’t, so it depends.

Sometimes I rather enjoy doing very difficult works with very little rehearsal

time — if the orchestra is good enough.

BD: Do you adjust your conducting style at all

for the size of the house — large house, small house?

E-PS: That is something I haven’t really thought

of. It might be true. [Thinks a moment] It might have

a certain effect on tempi and so forth, but I haven’t really thought

of it. The auditory response you get when you are conducting a piece

of music has a certain of effect on your next move. Your rehearsal

actually controls the next moment of making a decision of tempo, or phrasing,

but since a lot of those things happen in the basic nerve system instead

of cortex, it’s difficult to tell how much one adjusts.

BD: Have you done any opera at all?

E-PS: Very little. The only real opera

production I’ve done thus far was Wozzeck in Stockholm in ’84.

There were fifteen performances of a new production, and I haven’t done

any other operas except a couple of productions for the Swedish TV.

My next opera production is going to be next year in Florence at the Maggio

Musicale of Pelléas and Mélisande.

BD: Do you want to do a little more opera, or

do you find you just don’t have time for it? Or is it something that

doesn’t really interest you?

E-PS: Actually it does interest me. It’s

a question of planning, and also a question of time. I had a little

frustrating experience from my first opera production as I didn’t always

have the same players in my performances as I had in my rehearsals, and

in a piece like Wozzeck, it certainly does a lot of harm. So

immediately after those performances, I decided never again if I’m not

able to get different contracts. Now in Florence they promise that

I would have exactly the same players from the first rehearsal to the last

performance. So that’s why I thought it would be nice to try again.

Also the piece is one of my very favorite musical works, so I’m quite

excited about it.

BD: Are there some pieces that you like to play

over and over again, so you re-program them many times?

E-PS: Yes. It’s also a practical question

because there has to be a certain limit for your repertory. The

number of works you do in a season cannot be unlimited in terms of having

the necessary time for study. So you have to limit your repertory.

So there are some works that I conduct over and over again. Actually,

I had this funny experience. Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony is

one of those works I’ve conducted a lot lately, and last year in Los Angeles

I did three performances of it, and afterwards the orchestra manager told

me that the durations of all three performances happened to be identical

within three seconds.

BD: Does that make you happy?

E-PS: No, actually scares me a little bit because

then you will have reached the state where you function like a machine.

You’re not anymore a creative unit if you reach this sort of a scientific

accuracy in your tempi. So then I decided to leave that symphony

for a couple of years, and take it to my desk again to re-study and see

what I think about the work after a break.

BD: Will you come to it with a clean score?

E-PS: Yes, I’ll buy a new one without my old markings.

So now Sibelius Five is on sabbatical at the moment.

* * *

* *

BD: Do you like working with an orchestra for just

a week or two weeks at a time, and then moving onto the next orchestra

for a week or two weeks?

E-PS: That is actually something I am trying to avoid,

so I’m doing less and less pure guest conducting in the future. Typically

what happens is that you meet an orchestra and you play three or four

concerts with them. Then in the last concert, or the penultimate

concert, you feel you have actually reached a level of communication which

could be a good starting point, and then you’ve got to move to the next

place. So that is something which not artistically very satisfactory

in the long-run. It might be exciting, it might be interesting

— especially now when I meet orchestras like the Chicago Symphony,

or the Berlin Philharmonic. That’s always an exciting experience even

if you don’t reach the ideal state of communication during such a short

time. But in the future, I’ll guest conduct less and concentrate

more on a fewer number of ensembles, like four or five orchestras.

E-PS: That is actually something I am trying to avoid,

so I’m doing less and less pure guest conducting in the future. Typically

what happens is that you meet an orchestra and you play three or four

concerts with them. Then in the last concert, or the penultimate

concert, you feel you have actually reached a level of communication which

could be a good starting point, and then you’ve got to move to the next

place. So that is something which not artistically very satisfactory

in the long-run. It might be exciting, it might be interesting

— especially now when I meet orchestras like the Chicago Symphony,

or the Berlin Philharmonic. That’s always an exciting experience even

if you don’t reach the ideal state of communication during such a short

time. But in the future, I’ll guest conduct less and concentrate

more on a fewer number of ensembles, like four or five orchestras.

BD: From your point of view, what is the real

difference between a group such as the Chicago Symphony and maybe a group

of lesser renown? Is it just the technical perfection, or is there

something more?

E-PS: Each orchestra has its own personality, of

course. It’s a thing which is very difficult to describe, but the

Chicago Symphony is like a racehorse in the sense that to get a good result

from such an orchestra you don’t have to force things. Actually you

shouldn’t ever force things. You should just use small gestures and

just give hints and impulses instead of having a rigid type of command over

the players. Here you can give a lot of freedom to the players because

they have this discipline and they have this tradition. They know exactly

what to do, so it is different conducting an orchestra like the Chicago Symphony

from many other orchestras. Elsewhere the artistic level, the technical

level of the individual players might be as high or even higher, but there’s

not the same sort of discipline, not the same sort of unified musical thought.

So it is different.

BD: When you’re doing a concerto, whose ideas

override — your ideas or the soloist’s?

E-PS: The soloist’s because in most of the cases

the soloist has played the piece five hundred times, and I’m doing it for

the fifth time, or for the first time. Also, for a soloist who is

on tour with a piece which he plays over and over again, it’s much more difficult

for him to adjust to the conductor’s ideas. For a conductor it’s much

easier to adjust because it’s not a technical problem. You have to

be flexible in mind, whereas the soloist has to make different technical

solutions if there are different ideas about tempi and so forth.

BD: Do you enjoy accompanying concertos?

E-PS: Most of the time, yes, but of course there

are situations when you have a soloist who thinks completely differently,

and there’s no rapport whatsoever. Things can get very difficult,

but that doesn’t happen often.

BD: Then do you make sure you don’t work with

that soloist again?

E-PS: Perhaps, but even so, a professional musician

should be able to adjust. Even if it makes you mad, you should

be able to do it anyway.

BD: Is there anything you should not be expected

to do?

E-PS: [Ponders the question] From whose

point of view?

BD: We seem to have a picture of conductors as

being supermen. They can do anything, they can conduct anything, they

can bring anything to life.

E-PS: [Smiles] Well, this depends very much

as your mood varies from day to day. You’re doing basically the

same things with different orchestras, and the communication works in different

ways, so there are no safe cards, so to speak. There are no things

which are doomed to failure beforehand, so this is always something which

is flexible. But I know there are some composers who clearly are

more difficult for me than some other composers, and although in certain

cases I do like the music a lot, I just keep away from them myself.

BD: Is conducting fun?

BD: Is conducting fun?

E-PS: Most of the time, yes. The actual

act of conducting is mostly fun, but the sort of life which is the result

of having an international conducting career is not always as fun as the

conducting itself.

BD: Is it worth the sacrifices?

E-PS: Thus far I feel so, but in the future I’m

going to cut down my conducting weeks to get more time for my composition

work, and also more time for human life.

BD: You’re also a composer?

E-PS: Yes, that was my main subject in school,

actually. I’m trying to keep up with it, even though I am conducting

forty-five weeks a year. It’s difficult, so that’s one of the reasons

I’m going to cut down in the future.

BD: Do you feel that your compositions are perhaps

better because you are such an experienced orchestral director?

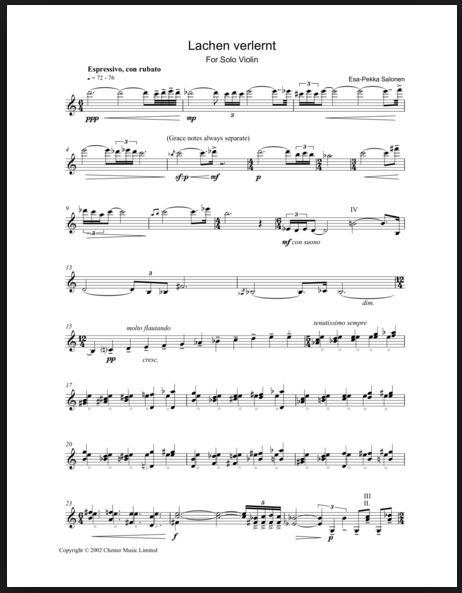

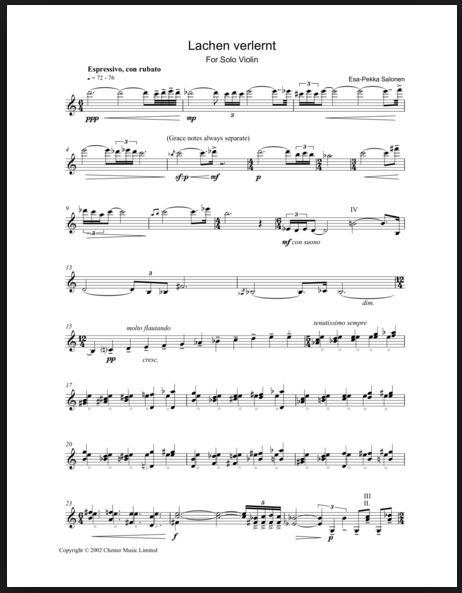

E-PS: I haven’t written anything for orchestra

since I started to conduct full-time. I’ve written some chamber

music, solo works, and a little electronic music, so that’s about all.

It’s simply a question of time because to write an orchestral score takes

so much time and needs so much concentration and energy that, at least for

me, it’s impossible to do while you are touring and when you’re not in

one place for a longer period.

BD: If you’re really a composer, why would you

get into conducting?

E-PS: I thought it might be useful for a composer

to know something about conducting, so I took conducting as a second

subject. Later on I realized that conducting was a good way to survive,

because as a composer you don’t survive in economic terms. I conducted

some contemporary music concerts, and conducted my own works, and so forth.

Then I got more conducting jobs, and I was appointed as a guest conductor

at the Finnish National Opera. After that I conducted in Stockholm,

and also Copenhagen, and then finally in London and in Los Angeles. So

I gradually realized that I was a full-time conductor. But I never

had any intention of being a full-time Kapellmeister.

BD: So then you relish the time that you can

spend composing?

E-PS: Yes.

BD: Are you the ideal interpreter of your music

when you conduct your own works?

E-PS: No. not at all. Actually I realized

several times that I become a very amateurish conductor when I’m conducting

my own music because there’s too much happening inside of your brain. In

that very moment when you rehearse your own works you hear music which

is basically very close to something you dreamed of, but it is not necessarily

exactly the same. So you start thinking whether the problem is in

the playing or in your conducting; whether the problem is your instrumentation

or were you not able to convey your ideas in musical notation. Then

you actually forget about the rehearsals and think about think other things.

So I prefer sitting in the audience listening, and have someone else conduct

my works. That has happened a couple of times, which is very nice.

I can even have a drink before the performance. [Laughs]

* * *

* *

BD: Where’s music going to day?

E-PS: [Laughs] It’s difficult to tell because

at the moment there are no major schools anywhere. In the ’50s

and early ’60s, you could always tell that there’s

this Darmstadt school, and there’s this other group which is not Darmstadt,

and that was basically the two polarities. Now there’s no such

a thing anymore, and so the whole thing is more diffused than ever, which

is nice, I think. There are even no pure minimalists anymore; there

are no pure serialists anymore. The computer is very strongly

there now — at least in Europe and in this country,

as well in certain other places. People do remarkable musical things

with computers, and the musical phenomenon of the ’80s

in musical history will probably be the digital synthesizers which make

digital sound synthesis possible for anyone. Now that micro-computers

can control all these digital synthesizers, that opens completely new

horizons for the development of electronic music that’s vital and revolutionary.

BD: Is there any chance there are perhaps too

many young composers coming along?

E-PS: I don’t know. It’s difficult to measure

what’s a right amount of composers for a culture. There is this Darwinist

mechanism of letting the strongest continue. [Laughs] It sounds

a little bit fascist, but it might be the case. In Europe, especially

Scandinavia, the public interest towards contemporary music and young composers

is perhaps growing at the moment. I don’t know really what is happening

in this country. It might be different. It is basically different

because this is a country of separate mini-cultures. The California

composers don’t necessarily know that much about the East Coast people,

and so this country’s divided into smaller cultural areas.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

E-PS: Yes, I am, actually. Otherwise I would do

something else if I didn’t feel there was a future for all this I’m doing

at the moment.

E-PS: Yes, I am, actually. Otherwise I would do

something else if I didn’t feel there was a future for all this I’m doing

at the moment.

BD: Tell me about the program you’re bringing in

a few weeks with your Swedish Radio Orchestra.

E-PS: The first piece is by a Swedish composer,

Karl-Birger Blomdahl (1916-1968), a piece called Forma Ferritonans.

Blomdahl was one of the most important modernists in the ’50s

and the ’60s.

BD: Did you ever conduct Aniara [the opera

set aboard a space ship headed for Mars]?

E-PS: No, but that was basically the most important

Scandinavian opera from the ’50s, and is probably

still the most important Scandinavian opera after the Second World War.

That was his main work. [Soprano Elisabeth Söderström,

who sang the leading role, speaks of this work in my interview with her.]

This piece we are bringing to Chicago – Forma Ferritonans

was written for a steel factory. They had an anniversary of some

kind, and they commissioned a piece by Blomdahl. It has a very steely

character, so it’s very exciting piece. Then the second piece in

the program is the Violin Concerto by Nielsen, played by Cho-Liang

Lin. It’s not a very well-known work but it’s gaining more popularity

— at least in Europe at the moment — and

after this tour we are going to record it. That recording is going

to be coupled with the Sibelius Violin Concerto. Then after

a break, we will play the Sibelius First Symphony. So it’s

an all Scandinavian program.

BD: Do you prefer to record music that you’ve

played in the concert hall?

E-PS: Oh, yes, always. That’s important in terms

of sheer rehearsal time because an orchestra learns a lot more about

the piece in a concert than they actually do in a rehearsal. It’s

such a different state of mind, such a different concentration.

BD: You can’t duplicate that in rehearsal?

E-PS: I cannot. I would imagine that some

sort of genius conductor like Carlos Kleiber can

make his rehearsals as interesting as concerts, but I have my doubts.

BD: Will you be back with the Chicago Symphony again?

[Remember, this interview was done at the time of his debut with

the Orchestra.]

E-PS: I hope so. We haven’t actually spoken

about it, but let’s see what happens.

BD: Have you been pleased with what you’ve been

hearing so far?

E-PS: Oh, yes. It’s been a tremendous experience,

and I enjoyed the collaboration very much. Although it’s world-famous

and very prestigious, the orchestra is very flexible, and has sort of

easy-going people as well. So I enjoyed it very much on a personal

level, too.

BD: Thank you for coming to Chicago, and for spending this

time with me today.

E-PS: Thank you.

=======

======= =======

--- --- --- ---

======= =======

=======

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 16, 1988.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later, and again in 1993

and 1998; and on WNUR in 2003, 2007, and 2009. This transcription

was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her

help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment

as a classical station in February of 2001. His

interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals

since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are

invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including

selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full

list of his guests. He would also like to call your

attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

BD: There must be some things you look for in the score

to give you a clue that this will excite you or that will not excite

you.

BD: There must be some things you look for in the score

to give you a clue that this will excite you or that will not excite

you. E-PS: The good thing about it is that the musical communication

beyond the limits of language is easier, so there can be more musical exchange

between different cultures without having big syntax problems. But

also it’s a pity that different countries lose their personal characteristics.

With all these satellite TV channels and videos and things there’s

a danger that our whole culture will become more impersonal and colorless

as a result of all these commercial mass-communication systems.

E-PS: The good thing about it is that the musical communication

beyond the limits of language is easier, so there can be more musical exchange

between different cultures without having big syntax problems. But

also it’s a pity that different countries lose their personal characteristics.

With all these satellite TV channels and videos and things there’s

a danger that our whole culture will become more impersonal and colorless

as a result of all these commercial mass-communication systems.

E-PS: No, I don’t believe in the polarity of heart and

brain in music. It’s a superficial analysis to divide musical personalities

into two groups — heart and brain — because

it’s too simple to be true. But I feel that the recording should

reveal something of a piece of music which doesn’t necessarily come out

in a concert situation, and ideally it would convey something which offers

a new aspect to that particular work.

E-PS: No, I don’t believe in the polarity of heart and

brain in music. It’s a superficial analysis to divide musical personalities

into two groups — heart and brain — because

it’s too simple to be true. But I feel that the recording should

reveal something of a piece of music which doesn’t necessarily come out

in a concert situation, and ideally it would convey something which offers

a new aspect to that particular work.  E-PS: That is actually something I am trying to avoid,

so I’m doing less and less pure guest conducting in the future. Typically

what happens is that you meet an orchestra and you play three or four

concerts with them. Then in the last concert, or the penultimate

concert, you feel you have actually reached a level of communication which

could be a good starting point, and then you’ve got to move to the next

place. So that is something which not artistically very satisfactory

in the long-run. It might be exciting, it might be interesting

— especially now when I meet orchestras like the Chicago Symphony,

or the Berlin Philharmonic. That’s always an exciting experience even

if you don’t reach the ideal state of communication during such a short

time. But in the future, I’ll guest conduct less and concentrate

more on a fewer number of ensembles, like four or five orchestras.

E-PS: That is actually something I am trying to avoid,

so I’m doing less and less pure guest conducting in the future. Typically

what happens is that you meet an orchestra and you play three or four

concerts with them. Then in the last concert, or the penultimate

concert, you feel you have actually reached a level of communication which

could be a good starting point, and then you’ve got to move to the next

place. So that is something which not artistically very satisfactory

in the long-run. It might be exciting, it might be interesting

— especially now when I meet orchestras like the Chicago Symphony,

or the Berlin Philharmonic. That’s always an exciting experience even

if you don’t reach the ideal state of communication during such a short

time. But in the future, I’ll guest conduct less and concentrate

more on a fewer number of ensembles, like four or five orchestras. BD: Is conducting fun?

BD: Is conducting fun?  E-PS: Yes, I am, actually. Otherwise I would do

something else if I didn’t feel there was a future for all this I’m doing

at the moment.

E-PS: Yes, I am, actually. Otherwise I would do

something else if I didn’t feel there was a future for all this I’m doing

at the moment.