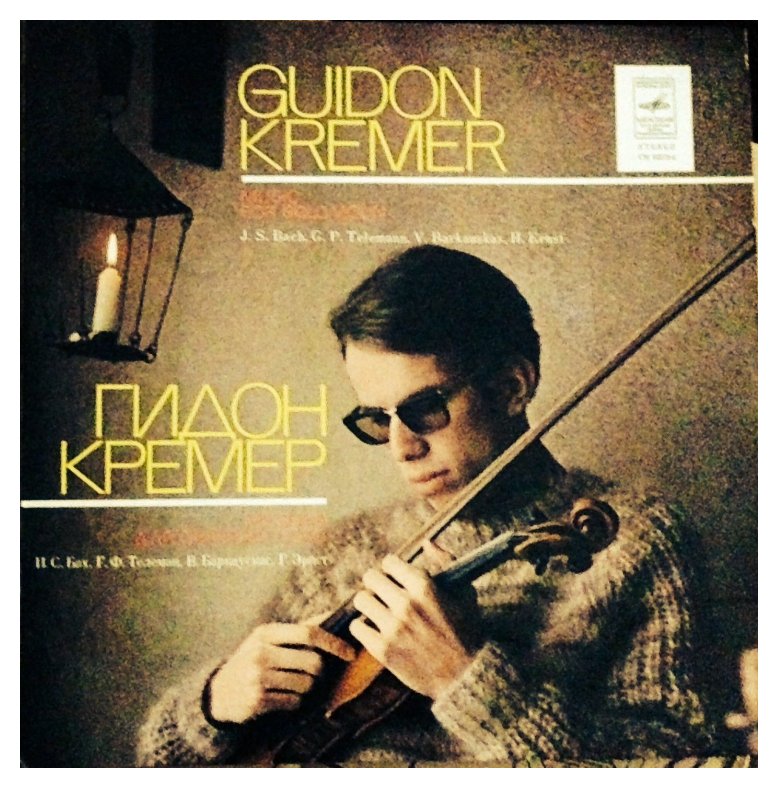

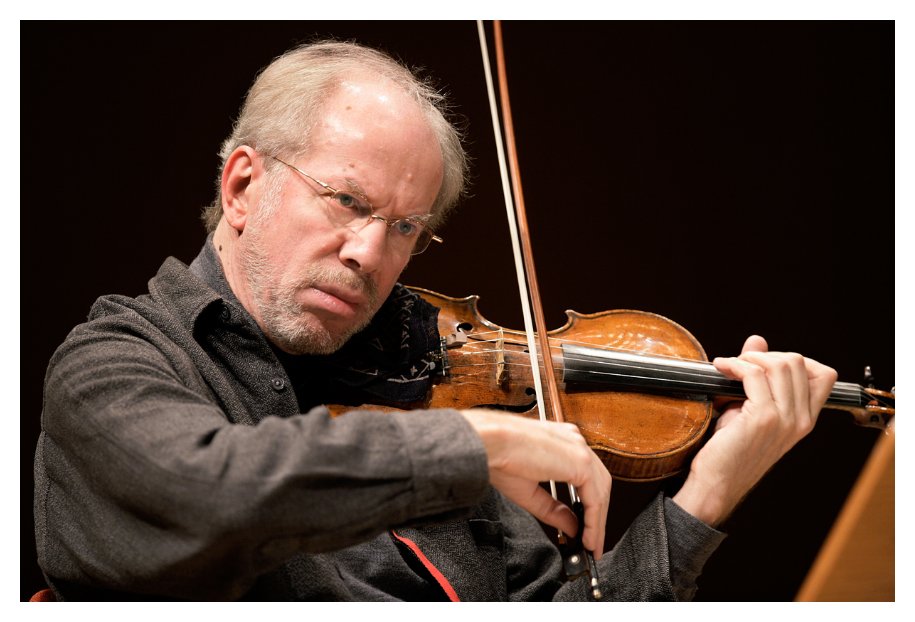

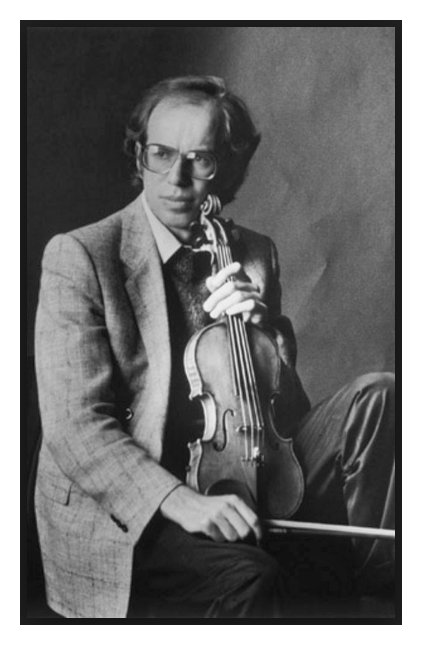

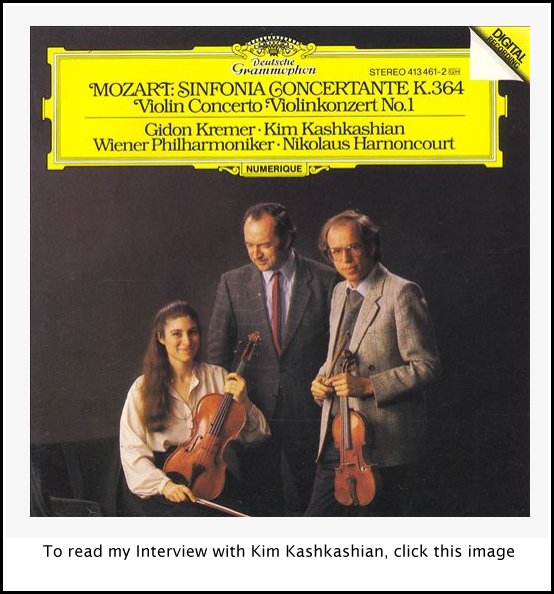

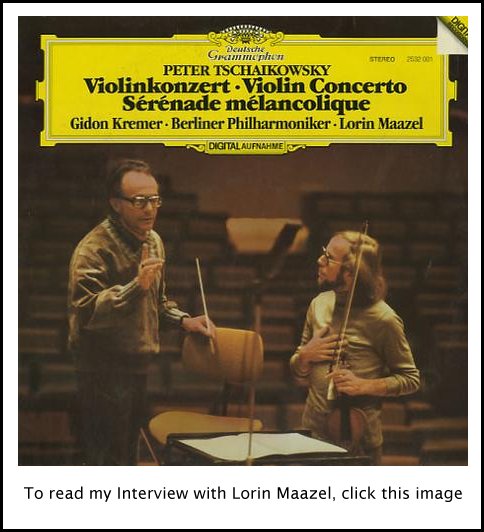

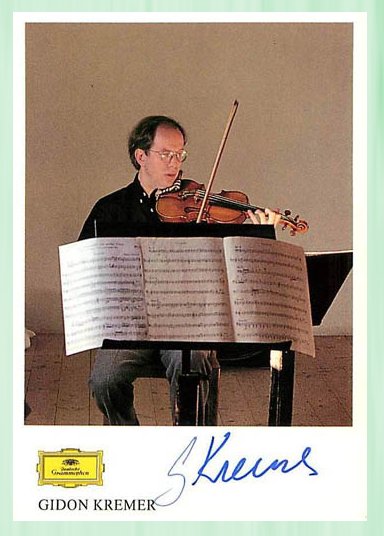

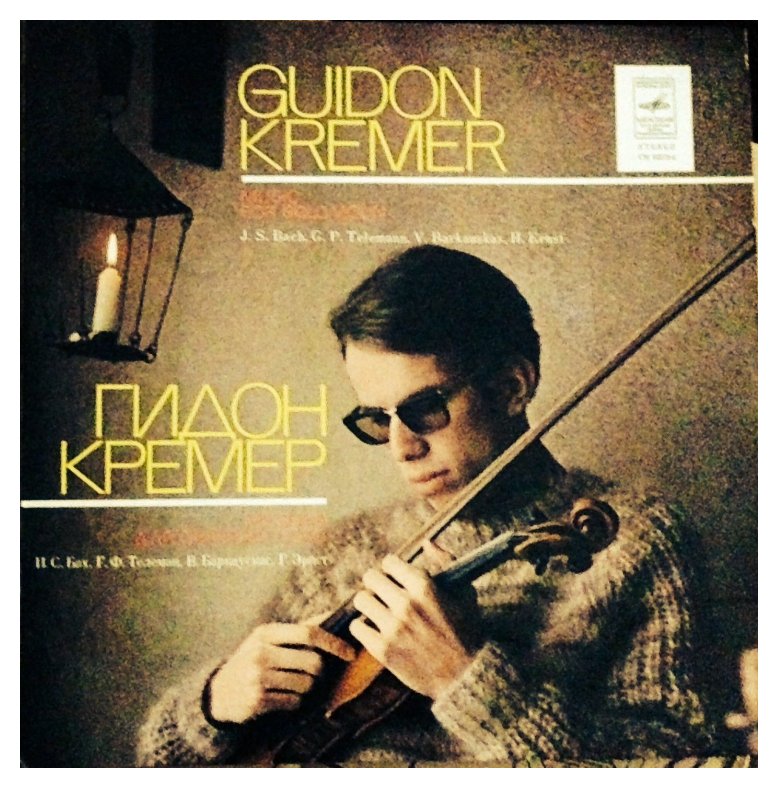

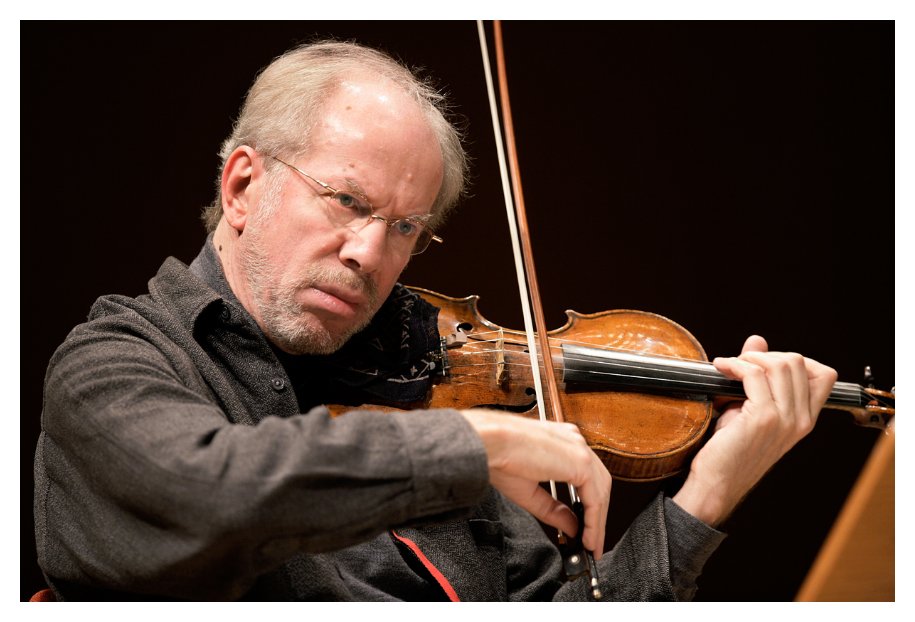

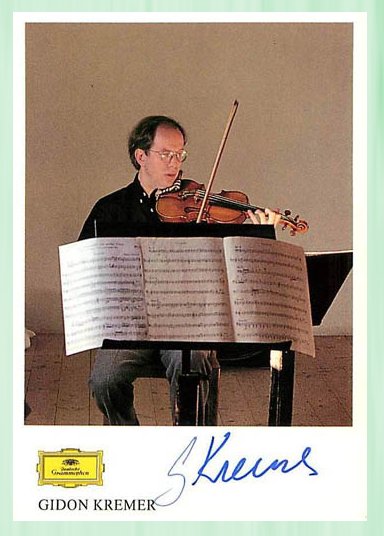

Violinist Gidon Kremer

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

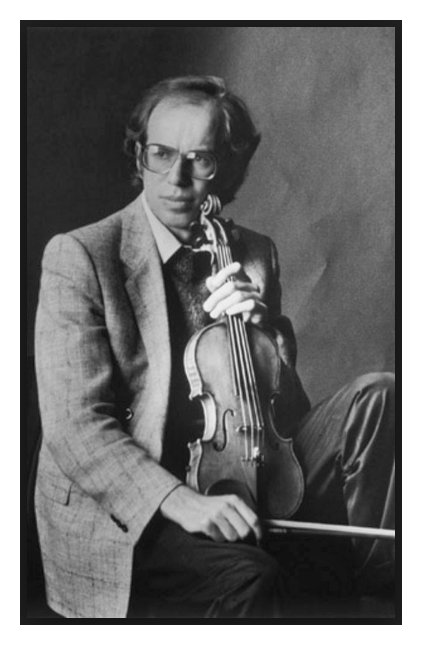

Gidon Kremer was born in Riga (Latvia)

in 1947, the only child of parents of German origin. After receiving his first

musical instruction at home - both father and grandfather were professional

violinists - he studied at the Riga School of Music and then at the Moscow

Conservatory under David Oistrakh. Kremer enjoyed notable success at competitions

in Brussels (1967), Montreal and Genoa (1969), and Moscow (1970). After extended

tours through the former Soviet Union, he began appearing with increasing

frequency in the West. His first concert in Germany came in 1975, followed

by debuts at the Salzburg Festival (1976) and in New York (1977). Gidon Kremer

was also one of the artistic directors of the music festival "Art Projekt

'92" in Munich.

The international chamber music festival in Lockenhaus (Austria), founded

by Gidon Kremer in 1981, has been a forum for young artists to present challenging

and innovative chamber music concerts - programmes which are also taken on

tour. In 1992 the festival in Lockenhaus was named "KREMERata MUSICA". In

1996 Gidon Kremer founded the KREMERata BALTICA chamber orchestra to foster

outstanding young musicians from the three Baltic states. He undertakes regular

concert tours with this orchestra. Gidon Kremer is also Director of the Musiksommer

Gstaad (Switzerland).

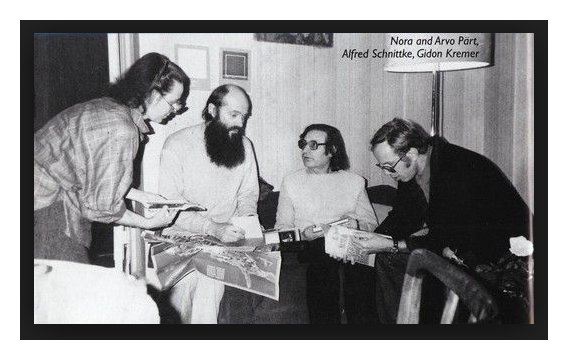

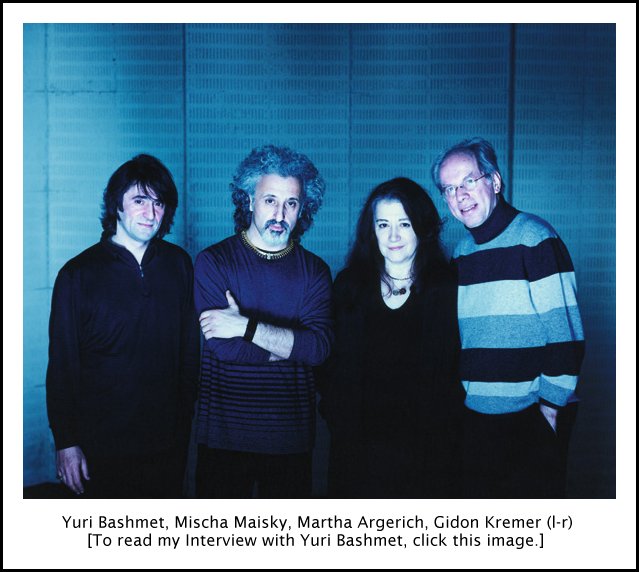

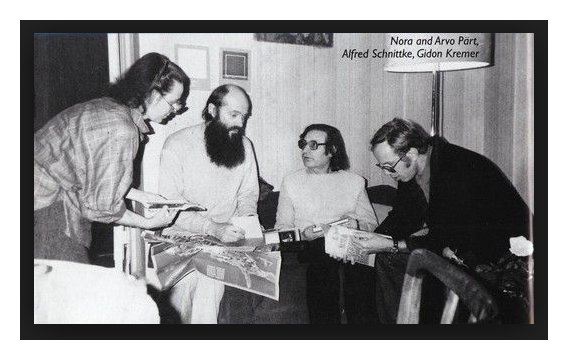

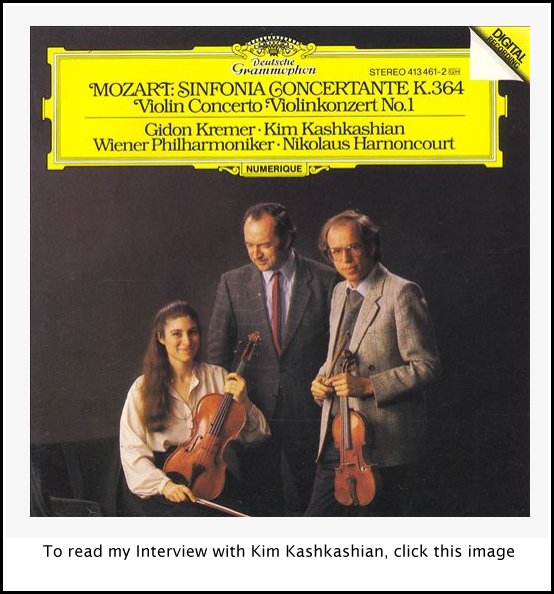

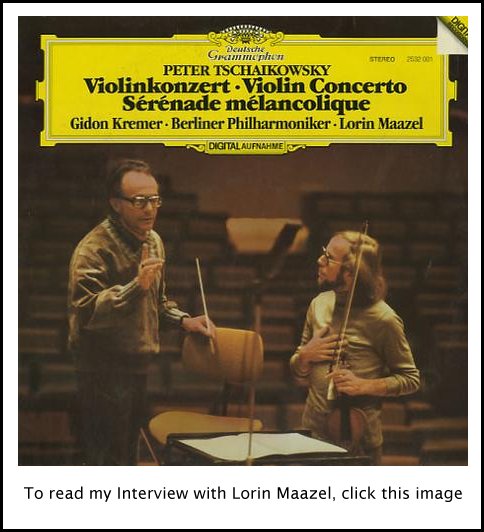

Gidon Kremer's repertoire ranges from the Baroque to works by Henze and Stockhausen. Composers

of the former Soviet Union such as Schnittke, Pärt, Gubaidulina and Denisov have been introduced

to Western audiences largely through Kremer's efforts. Martha Argerich, Valery

Afanassiev, Oleg Maisenberg and Vadim Sakharov are some of his favorite musical

partners. Gidon Kremer plays a Guarneri del Gesù - ex David - dating

from 1730.

-- Names which are links (both

in this box and below) refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website.

|

Kremer has been in Chicago on several occasions, and in May of 1997 he

agreed to meet with me for a conversation. On that visit he was giving

the world premiere of the Violin Concerto

by Aribert Reimann,

with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Daniel Barenboim.

Having admired both his artistry and his wide selection of repertoire,

I was glad he discussed the entire range of material with me that day . .

. . . . .

Bruce Duffie:

I would assume that you have, perhaps, one of the largest repertoires of

any violinist. How do you decide what you’re going to play and what

you’re not going to play?

Gidon Kremer: I make decisions of that kind for

a number of reasons. I have a long-standing relationship with a number

of wonderful composers that come from Russia, or from the ex-Soviet Union.

I should mention Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arvo Pärt, Valentyn

Sylvestrov, and Edison Denisov. Recently I got very involved playing

— and enjoying in fact — the music of the

Georgian composer Giya

Kancheli. Beside that, I’m always open-minded to meet composers

from other worlds, and so I was lucky and privileged to have cooperated with

the great Luigi Nono, and with a number of American composers like Ned Rorem or Philip Glass, and most recently,

John Adams, and Japanese composers like Yūji Takahashi or Tōru Takemitsu.

Most of the time these are working relationships, and they help me to understand

not only what an author wanted in this particular piece, but in general they

help me to approach the whole area of contemporary music much better.

But not only to approach better contemporary music, but also to understand

here and there what the lab of the great classics was or still is.

I learned a lot about music in general by playing contemporary music.

Gidon Kremer: I make decisions of that kind for

a number of reasons. I have a long-standing relationship with a number

of wonderful composers that come from Russia, or from the ex-Soviet Union.

I should mention Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arvo Pärt, Valentyn

Sylvestrov, and Edison Denisov. Recently I got very involved playing

— and enjoying in fact — the music of the

Georgian composer Giya

Kancheli. Beside that, I’m always open-minded to meet composers

from other worlds, and so I was lucky and privileged to have cooperated with

the great Luigi Nono, and with a number of American composers like Ned Rorem or Philip Glass, and most recently,

John Adams, and Japanese composers like Yūji Takahashi or Tōru Takemitsu.

Most of the time these are working relationships, and they help me to understand

not only what an author wanted in this particular piece, but in general they

help me to approach the whole area of contemporary music much better.

But not only to approach better contemporary music, but also to understand

here and there what the lab of the great classics was or still is.

I learned a lot about music in general by playing contemporary music.

BD: Do you advise

that all violinists play some contemporary music to better understand Beethoven

and Mozart?

GK: I think Beethoven

and Mozart helps also to understand which of the contemporary composers is

better or worse. Beethoven, Schubert, Mozart, Bach definitely; they

don’t belong only to the past. They accompany us, and will accompany

the future generations. I feel very strongly that music doesn’t belong

to a museum, and therefore, since my young days when I was an adolescent,

I actually felt very interested in playing contemporary music as well.

I always tried to balance things by playing a lot of the well-known pieces

on one hand, and on another hand introducing something unknown. But

the unknown is not always only related to contemporary music. Here and

there it is also something that was forgotten or was never discovered in

the past. I had big pleasures discovering composers like Erwin Schulhoff

or Artur Lourié, just to give you an example.

BD: What is it

that makes you decide, “Yes, I want to spend time learning this piece,” or,

“No, I think I’ll put this piece aside?”

GK: Here and

there it’s a commission that I am encouraged to contribute to by some friends,

by some colleagues, by some people that I trust. Here and there it’s

a visual aspect of a score that convinces me that this is a wonderful score.

Because in contemporary music you can’t always hear immediately what it is

like, here and there you learn to see it just looking at the score.

Here and there I get interested because I follow some performances or listen

to some tapes of composers which I before wouldn’t have known. I’m glad

that in this way my repertoire really got very large. At the same time,

I have to admit that I get hundred times more scores being sent to me in

the hopes that I will perform. I have to disappoint so many composers

that I always feel guilty. [Both laugh] But in a lifetime, you

can really do just a little, and my little contribution consists of the effort

to include every season two, three, four new pieces into my repertoire.

It’s the best I can do. Sometimes there are chamber music performances

along with some concertos. Occasionally it’s only chamber music.

That depends, but in the year ’97 I actually commissioned six pieces, so I’m

over the average. But this relates to my fiftieth birthday, and also

to the fact that I’m trying — as many musicians are

these days — to celebrate Schubert. I’m doing

a Schubert cycle consisting of six different programs — all

works for violin and piano, and violin and orchestra, and selected works of

chamber music. And on each of these evenings I include at least one

premiere.

BD: Schubert

and something new?

GK: Schubert

and something new, yes. In January I performed with the German Chamber

Orchestra, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie, a new opus by Sofia Gubaidulina called

Impromptu. I also played with

them a piece by a wonderful Russian composer, Alexander Vustin, Fantasy for Violin and Chamber Orchestra,

which I hope to introduce next year in this country at Carnegie Hall with

the Orpheus Orchestra. I played recently a new piece by Giya Kancheli

for violin and piano, which he wrote for me after I played at least fifteen

times, his big Lament for Violin, Voice

and Big Orchestra. This new piece of his is called Time and Again. It’s a wonderful

piece, which I just did in Europe during the third segment of my Schubert

cycle in all big cities of Europe. And in the summer I am going to premiere

a new piece by a Latvian composer, Peteris Vasks, who is just in process

of writing a violin concerto for myself and the newly formed chamber orchestra,

Kremerata Baltica, which consists only of members of the three Baltic states.

We just played our first concert on the ninth of February in my home town

of Riga.

BD: It’s an amazing

schedule; I don’t know how you keep it up! When you get a new score,

do you know how long it will take to get into your fingers and, perhaps more

importantly, into your psyche?

GK: [Laughs]

I’m trying to understand it, of course, immediately. Usually it takes

some weeks, and occasionally it takes some months. For example, for

this premiere of the Aribert Reimann Concerto,

I worked probably something like three months consistently because this piece

was really big challenge, not only for the fingers, but also for the ear.

I’m glad that I could premiere this piece in Chicago, and I’m looking forward

to play it with the Chicago Symphony in Europe.

BD: Do you take

into account the audience that’s going to be listening to each new piece?

GK: Glen Gould once said, “The relationship is

not the artist and the audience. It’s one to one, the artist and the

score.” I would say I want to bring the music to the audience, but

if I believe in a score, then it doesn’t matter to me if one person or thousands

will appreciate it. I do find there’s much more positive impact if

something is also liked by a large number of people, like the latest Piazzolla

record which had such a big success. I feel wonderful because I love

this music. I didn’t do it for commercial purposes, but it was found

by a large audience. But I believe as much in Piazzolla as in Kancheli,

and if Kancheli is today not as well known, it doesn’t matter. Some

day in the future people will appreciate him more, like they learned to appreciate

Alfred Schnittke within the last twenty-five years. My approach didn’t

change. I stayed loyal during this twenty-five years to Schnittke,

even at the times when nobody wanted it to be performed. Now he seems

to be a classic of the end of the century. So it’s wonderful to follow

it up, and to participate in this process.

GK: Glen Gould once said, “The relationship is

not the artist and the audience. It’s one to one, the artist and the

score.” I would say I want to bring the music to the audience, but

if I believe in a score, then it doesn’t matter to me if one person or thousands

will appreciate it. I do find there’s much more positive impact if

something is also liked by a large number of people, like the latest Piazzolla

record which had such a big success. I feel wonderful because I love

this music. I didn’t do it for commercial purposes, but it was found

by a large audience. But I believe as much in Piazzolla as in Kancheli,

and if Kancheli is today not as well known, it doesn’t matter. Some

day in the future people will appreciate him more, like they learned to appreciate

Alfred Schnittke within the last twenty-five years. My approach didn’t

change. I stayed loyal during this twenty-five years to Schnittke,

even at the times when nobody wanted it to be performed. Now he seems

to be a classic of the end of the century. So it’s wonderful to follow

it up, and to participate in this process.

BD: You say you

don’t care how many people listen at any one time. Are we just eavesdropping

on your relationship to this score?

GK: No.

What does it mean ‘eavesdropping’?

BD: Listening

in, almost surreptitiously.

GK: I don’t know.

I am very selective, after all, and I don’t want to say that my repertoire

represents the whole scale of good works of contemporary composers.

There are other performers that pick up other scores, and I like to listen

to them. I make my choices, and I make my choices for very subjective

reasons. Each time I choose a piece, I really hope the audience will

also like it, somehow. Unconsciously, this is one of the reasons that

I’m still performing. If I wouldn’t believe that I can share my emotions,

if I wouldn’t have the evidence that many of the performances that I gave

of contemporary works would have resonance, then I would probably give up

performing and traveling, because it’s a very difficult kind of life.

BD: That’s what

makes it all worth it?

GK: [Laughs]

Yes, somehow. If you see a happy face of a composer, or if you see someone

from the audience or some of your colleagues being excited about something

that you have just done for the first time, this, of course, is a big support.

BD: Does it do

your heart good when something you’ve premiered is then picked up by other

violinists?

GK: Of course.

If a piece becomes popular with time, I feel I’ve somehow helped it, like

Tabula Rasa of Arvo Pärt, which

became such a popular piece, or a concerto grosso by Schnittke, a piece which

was dedicated to myself and my partner Tatiana Grindenko, which also became

a rather known piece of contemporary music. So I’m always in favor if

pieces are picked up that I gave birth to.

* *

* * *

BD: Do you play

the same for the microphone as you do for a live audience?

GK: I think so.

It’s quite difficult to catch emotions in an empty studio because there are

many aspects of it that interfere — especially the editing.

I feel like recordings that are done from a live concert have occasionally

more integrity because the editing is very minimal. While in the studio,

you’re giving yourself completely. You’re fully engaged in the process,

and you repeat the same thing for eight or ten times. I’m doing it

with my full dedication, but at the same time I know that the editing is

a very dangerous thing. Only if you are used to working with certain

producers, then you can reach better results. If you are at the mercy

of some unknown person, it’s like being in a completely unknown restaurant

and not knowing what kind of food you are going to be served. Occasionally

you are lucky, but there are also many disappointments.

BD: So you

have to build up trust with your producer?

BD: So you

have to build up trust with your producer?

GK: That’s right,

and after having recorded more than a hundred CDs, I feel also that I’ve worked

with too many producers in the past. Now I am trying to concentrate

on certain producers, and I feel much more comfortable. In the past

there was too many distortions of what I actually tried to do in the studio

— not that I was always perfect, but still this interference of

some alien mind and some alien ears is a very dangerous thing. That’s

why I think Glen Gould found for himself the best way of editing

— he did it himself!

BD: Are you involved

in the editing process, or do you leave that to others?

GK: No, I am

involved only at last stage of it. When the first edit is done, I listen

to it very carefully and come up with my 187 wishes, which hopefully can

be fulfilled and repaired. But this is not always the case, and sometimes

I’m misunderstood as well.

BD: Of your 187

wishes, do you get 170 of them, or do you get 32 of them?

GK: I’m following

it up, so at least a good seventy percent of it would be done.

BD: Perhaps more

in performance than in recording, but is there such a thing as a perfect performance?

GK: No, and there

shouldn’t be. As Nikolaus Harnoncourt put it a couple of times, “Perfection

is the worst enemy of beauty because humans can’t be perfect.” We can

just try for perfection, but we can never be as perfect as the deep blue,

for example. At the same time, fantasy and the spirit of the human being

is much more interesting. Perfectionism that I was vaccinated with

in my childhood and my years of study also became my enemy, because of course

you want to be as precise, as correct, as possible. You want to be

as loyal to the composer as possible, and these should all be ingredients

of a good performance. Finally, perfection is not what matters, but

something between the lines. All that is in between the lines are

distortions of perfectness. I’m preparing myself now to play the Alban

Berg Concerto with two different

orchestras and two different conductors. Both of them great

— the Berlin Philharmonic and Abbado, and Vienna Philharmonic

and Harnoncourt. I have had this piece in my repertoire for almost

twenty years, and within the next ten days I’m going to give seven performances

with two different minds in front of me. I’m trying to be flexible

to their wishes, and I’m trying to imagine that I will to discover new things

in the concerto for myself. So I did something very unusual because

normally I wouldn’t listen to recordings of the concerto — neither

to my own ones nor to other violinists. But there is this recording

of Louis Krasner giving one of the first performances in 1936 with Anton

Webern conducting, and this morning I listened to it. I thought it’s

wonderful because it’s so personal. It’s so full of expression, but

it’s not a performance which you can say is perfect. It’s not perfect

sound-wise and it’s not perfect in the vertical lines, but it’s perfect in

a musical sense, and this perfectness, this outstanding personal interpretation,

is the best one can find on records. The same holds with Astor Piazzolla.

It’s not his perfect playing on the bandoneon; it’s the spirit that matters.

When he is around, it seems like musicians play differently than without

him.

BD: So the perfection

is just a technical thing, but the artistry is what makes it?

GK: Of course.

I would say for me an artist is perfect that is full of fantasy, full of challenge,

and likes to take risks. Especially because you are taking risks, you

are exploring a borderline, and on this razor’s edge you never meet real

perfection. You can see operations and you can reach out for more than

perfection, but perfection kind of kills it. You could be idiomatically

perfectly right or academically perfectly right, but the performance would

be awful.

BD: [Laughs]

I see. It would just fall flat.

GK: Yes, and

I feel we are living in a time when this perfection is expected

— especially because of the record industry. Because of

the number of records existing and still being produced and being sold, we

are in a dangerous time when perfection counts more than artistry.

Therefore, we have fewer personalities than maybe in the past, when there

was much less business going on.

BD: Is it safe

to assume that in the best performances, each one points out different aspects

of the piece?

GK: Of course,

and they can be quite contrary to each other. A wonderful piece of music

allows different interpretations, and I feel no composer should be satisfied

with just with one way of looking at his score.

BD:

When you give a commission to someone, do you give them any pointers or

any ideas, or do you just say, “Write me a piece?”

GK: No.

Here and there the piece is related to a combination of players; here and

there it’s related to a theme, to an occasion, to a celebration, so there

are different aspects of it. I can’t tell them what the impact is.

I’m trying to encourage the composer to do as much as he wants to express,

so I’m giving him the allowance to explore things which he never did before.

But if I’m sent a score which was not discussed with me beforehand, I’m also

quite open minded. I’m trying to figure out what is new to me in this

particular score. Most of the time scores that were given in commission

were performed by myself. There are only a couple of cases when I said,

“I’m terribly sorry, but I really don’t feel it’s my piece.” Occasionally

it happens that I would say such a thing after giving it birth and playing

it a couple of times and not feeling at home, but most of the times I was

lucky to get pieces which actually were jewels.

* *

* * *

BD: Let me ask

a real easy question. What’s the purpose of music?

GK: I think music

is there as a language that can bring us closer to each other if we are allowing

ourselves to open up and not just consider music as something that is a driving

force like a beat in the pop music. If we can open up and look at music

and at musicians as colleagues, as partners in a dialogue, music is something

that can give us a lot of discovery. With music we get a companion for

adventures, and therefore I feel music that is easy listening, or music that

is assumed to be a convenient accompaniment to our meals or our shopping is

dangerous. Like pollution in the air, there’s also a pollution in the

sound, and all this kind of convenient music disturbs me enormously.

BD: Is it

convenient music, or is it simply non-music?

BD: Is it

convenient music, or is it simply non-music?

GK: Yes, you

would be closer to it by saying it’s non-music if the pieces would be so

often, for whatever reason, classics taken for that kind of use. I’m

so fed up with listening to the Four Seasons

or the Mozart concertos in hotel rooms, and I really don’t believe that the

spaghetti that is produced by the influence of classical music, or the milk

that cows produce that listen to classical music is better. [Both laugh]

BD: Would you

be horrified to hear one of your recordings in an elevator?

GK: Yes.

If I walk into a restaurant and I hear violin music, I almost always ask the

waiter to stop it, or to change the channel. I’m very seldom listening

to myself, but violin sounds are something that I live so much with that if

I want to have a discussion with a friend or a nice meal, I’d rather leave

it out.

BD: When you

perform, where is the balance between the artistic achievement and an entertainment

value?

GK: I know that

in America very often classical music is put in the leisure or entertainment

department, and I feel strongly that this is wrong. I have nothing against

entertainment, because in this very dangerous and troublesome world, entertainment

can also be a necessary and wonderful distraction. But I don’t consider

my own preoccupation with music any kind of entertainment. I even don’t

consider playing tangoes by Astor Piazzolla an entertainment. I think

it’s full-value music. Piazzolla just happens to be one of the great

composers of this century.

BD: Did he not

consider it entertaining?

GK: Here and

there they are lovely pieces that you could compare with waltzes by Chopin,

which can also have their entertaining value in itself. But I don’t

think music in general should be considered as an entertainment. I

feel music has much more power in it, and music can be much better than only

entertaining. As I said, I have nothing against entertainment.

I like to be entertained myself. Music, as a profession, for me is

much more than just entertainment. So when I walk on stage, I want

to share some emotions; I want to pass on some sentiments; I want to also

give the idea that a certain composer could be quite witty, and I hope that

here and there I am understood. Talking about entertainers, last night

I went to a performance by the 88-year-old Victor Borge, and he is really

an entertainer. But he is such a classy entertainer that it’s also

more than just entertaining. He tickles someone’s mind in his audience

as well, and he is a wonderful, gracious piano player. Of a whole

generation, he’s maybe one of the last to be around.

BD: It seems

that his entertaining and his comedy comes from a deep, genuine love of the

music.

GK: Yes, that’s

right. We all can have our pleasure of falling in love and meeting someone

challenging, but what conducts our life is deeply felt love, and finally

this is what matters. As love still is in the heart of Victor Borge,

so love could be felt in every piece by Astor Piazzolla. This is love

not only of the music; that is probably just love of life, and this is a

sensation which in many perfect performances is lost.

BD: Is it safe

to assume that you fall in love with each piece that you play?

GK: Walking on

stage, I feel I have to be in love, even if I dismiss a certain piece afterwards

or after a couple of performances. As I said, not all premieres would

last for years, but I would make a fool of myself if I would walk on stage

and not love music that I play.

BD: Is the music

that you play for everyone?

GK: I don’t know...

maybe not for everyone. I was told by a manager in England some fifteen

years ago, “Oh Gidon, you are so special! You are not for everyone,

so not everyone can appreciate how special you are.” [Laughs]

I think that’s silly. If there is something personal in what I do, someone

that appreciates the meaning of this which is personal will find his way

to it. This doesn’t mean that every piece I play has to be liked by

everybody, but the way I approach music can be a matter for a number of music

lovers. I’m not trying to make myself popular, so I’m not trying to

make things which audiences would necessarily like more because they are

easy to access. The quantity of concerts that you play or the quantity

of records that you sell doesn’t speak about quality. The majority

of people and majority of music lovers are consumers of something that is

easy. I don’t think to live is easy, but many people want to consider

art or music or something that relates another to be easy rather than be

challenging or adventurous or difficult. I don’t want to discourage

people from contemporary music because I feel there is a misunderstanding.

Very often people think contemporary music is too difficult because it has

to be understood. Good contemporary music doesn’t have to be understood.

Giya Kancheli or Leonard Bernstein or Astor Piazzolla all can be felt.

Music is about feeling, but you can learn more about the piece if you actually

get involved and listen to more of this composer. When you read something

about music, you get much more pleasure out of it, but the easygoing thing,

the ‘rock’ of the classical world

is something I can’t deal at all with. But millions do. So if

my producer at Nonesuch says, “Oh, wonderful — we sold

already more than a hundred thousand records of Piazzolla,” I’d say, “Wait

a minute... Vanessa-Mae sells millions!” [Both laugh] This is

an ironic comment, but it’s an ironic comment on the taste of the larger audience.

BD: Is this what

makes a piece of music great — that it exists on so

many levels?

GK: Oh, yes.

But I hope that a good pieces of music is not distorted to such a degree that

it becomes easy listening.

BD: Should you

try to go after the rock music audience, or the basketball audience?

GK: No.

I don’t have the goal to achieve as many people as possible in this, my small

single life. I’m trying to be as loyal to music as I can, and if this

is appreciated, I’m happy.

* *

* * *

BD: Do you have

any advice for composers who want to write contemporary music, or contemporary

music for the violin?

GK: Yes, I would

have one bit of advice. Mauricio Kagel, an Argentinian

born German composer said that there are composers that write pieces for other

composers. My advice to a composer would be not do that. After

all, music is a matter of dialogue with an audience, so you need to give

the audience a chance, even at the first listening, to get the desire to

listen to it once more. If the impact of the piece is emotionally strong

and not just rational, this desire will appear.

GK: Yes, I would

have one bit of advice. Mauricio Kagel, an Argentinian

born German composer said that there are composers that write pieces for other

composers. My advice to a composer would be not do that. After

all, music is a matter of dialogue with an audience, so you need to give

the audience a chance, even at the first listening, to get the desire to

listen to it once more. If the impact of the piece is emotionally strong

and not just rational, this desire will appear.

BD: [With a gentle

nudge] So you don’t like ‘academic music’?

GK: [Smiles]

I don’t like academic music. I don’t like academic musicians or academic

composers. I have a lot of respect for knowledge, and working with such

a wonderful conductor like Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who is very often, as the

cliché goes, labeled — as I am here and there

— ‘intellectual’,

which is completely wrong. Working with such a musician, I learned

that to know something is always an additional power. But if you know

something about the tradition, that doesn’t mean you have to fall on your

knees and just try to be as loyal as possible to that tradition, and that’s

all the impact you have to give to a performance. This is just a matter

of roots. Contemporary music has its roots in the past, and we have

to explore this past as much as we can. But here and there we have to

take off the dust that the wrong tradition got on it.

BD: In that case,

I would think it would be almost ideal to have someone like Harnoncourt, who

specializes in early music and early performance, to do the Berg concerto

with you.

GK: That’s right.

He was a specialist in Baroque music, but in the meantime he went on.

He recorded as much Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, and Schumann as any other big

conductor. I guess Alban Berg is still a novelty for him, and I’m full

of expectation how he is going to face it.

BD: Are you optimistic

about the future of musical composition?

GK: If I’m looking

at the charts, no. [Both laugh] But to walk on stage and to live

this troublesome, troubling life, you have to have within yourself a certain

optimism. Otherwise it would be too depressing. But the future

of music depends on musical education, and I’m quite worried that this musical

education is reduced to a minimum these days. Where should we take new

audiences if the kids would not learn that there is such a precious thing

as music? If they learn only about music what is on MTV, this is a

depressing thought.

BD: Does that

mean that you should be on MTV?

GK: No, I don’t

think I belong there.

BD: Why not?

That’s a way to grab them.

GK: [Laughs]

I’m not sure. I feel like this is also a very commercial enterprise,

and even I’m glad if something that I do finds a large audience, I don’t want

to be commercialized.

BD: You have

just passed your fiftieth birthday. Are you at the point in your career

that you want to be at this age?

GK: In my career

I have reached much more than I dreamed about in my youth. I did quite

well, and I’m still curious; I’m still full of ideas. I was quite worried

to reach this age of fifty, because it seemed like a mountain which you never

want to climb on. But now, after I passed the peak of it, it feels a

bit easier, and I hope still to enjoy music in the future.

BD: Thank you

for sharing all that you have given us so far. We look forward to even

more.

GK: Thank you.

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 19, 1997. Portions

were broadcast on WNIB later that year. This transcription was made

in 2014, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with

WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment

as a classical station in February of 2001.

His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series

on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests.

He would also like to call your attention to the photos

and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Gidon Kremer: I make decisions of that kind for

a number of reasons. I have a long-standing relationship with a number

of wonderful composers that come from Russia, or from the ex-Soviet Union.

I should mention Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arvo Pärt, Valentyn

Sylvestrov, and Edison Denisov. Recently I got very involved playing

— and enjoying in fact — the music of the

Georgian composer Giya

Kancheli. Beside that, I’m always open-minded to meet composers

from other worlds, and so I was lucky and privileged to have cooperated with

the great Luigi Nono, and with a number of American composers like Ned Rorem or Philip Glass, and most recently,

John Adams, and Japanese composers like Yūji Takahashi or Tōru Takemitsu.

Most of the time these are working relationships, and they help me to understand

not only what an author wanted in this particular piece, but in general they

help me to approach the whole area of contemporary music much better.

But not only to approach better contemporary music, but also to understand

here and there what the lab of the great classics was or still is.

I learned a lot about music in general by playing contemporary music.

Gidon Kremer: I make decisions of that kind for

a number of reasons. I have a long-standing relationship with a number

of wonderful composers that come from Russia, or from the ex-Soviet Union.

I should mention Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arvo Pärt, Valentyn

Sylvestrov, and Edison Denisov. Recently I got very involved playing

— and enjoying in fact — the music of the

Georgian composer Giya

Kancheli. Beside that, I’m always open-minded to meet composers

from other worlds, and so I was lucky and privileged to have cooperated with

the great Luigi Nono, and with a number of American composers like Ned Rorem or Philip Glass, and most recently,

John Adams, and Japanese composers like Yūji Takahashi or Tōru Takemitsu.

Most of the time these are working relationships, and they help me to understand

not only what an author wanted in this particular piece, but in general they

help me to approach the whole area of contemporary music much better.

But not only to approach better contemporary music, but also to understand

here and there what the lab of the great classics was or still is.

I learned a lot about music in general by playing contemporary music. GK: Glen Gould once said, “The relationship is

not the artist and the audience. It’s one to one, the artist and the

score.” I would say I want to bring the music to the audience, but

if I believe in a score, then it doesn’t matter to me if one person or thousands

will appreciate it. I do find there’s much more positive impact if

something is also liked by a large number of people, like the latest Piazzolla

record which had such a big success. I feel wonderful because I love

this music. I didn’t do it for commercial purposes, but it was found

by a large audience. But I believe as much in Piazzolla as in Kancheli,

and if Kancheli is today not as well known, it doesn’t matter. Some

day in the future people will appreciate him more, like they learned to appreciate

Alfred Schnittke within the last twenty-five years. My approach didn’t

change. I stayed loyal during this twenty-five years to Schnittke,

even at the times when nobody wanted it to be performed. Now he seems

to be a classic of the end of the century. So it’s wonderful to follow

it up, and to participate in this process.

GK: Glen Gould once said, “The relationship is

not the artist and the audience. It’s one to one, the artist and the

score.” I would say I want to bring the music to the audience, but

if I believe in a score, then it doesn’t matter to me if one person or thousands

will appreciate it. I do find there’s much more positive impact if

something is also liked by a large number of people, like the latest Piazzolla

record which had such a big success. I feel wonderful because I love

this music. I didn’t do it for commercial purposes, but it was found

by a large audience. But I believe as much in Piazzolla as in Kancheli,

and if Kancheli is today not as well known, it doesn’t matter. Some

day in the future people will appreciate him more, like they learned to appreciate

Alfred Schnittke within the last twenty-five years. My approach didn’t

change. I stayed loyal during this twenty-five years to Schnittke,

even at the times when nobody wanted it to be performed. Now he seems

to be a classic of the end of the century. So it’s wonderful to follow

it up, and to participate in this process. BD: So you

have to build up trust with your producer?

BD: So you

have to build up trust with your producer? BD: Is it

convenient music, or is it simply non-music?

BD: Is it

convenient music, or is it simply non-music? GK: Yes, I would

have one bit of advice. Mauricio Kagel, an Argentinian

born German composer said that there are composers that write pieces for other

composers. My advice to a composer would be not do that. After

all, music is a matter of dialogue with an audience, so you need to give

the audience a chance, even at the first listening, to get the desire to

listen to it once more. If the impact of the piece is emotionally strong

and not just rational, this desire will appear.

GK: Yes, I would

have one bit of advice. Mauricio Kagel, an Argentinian

born German composer said that there are composers that write pieces for other

composers. My advice to a composer would be not do that. After

all, music is a matter of dialogue with an audience, so you need to give

the audience a chance, even at the first listening, to get the desire to

listen to it once more. If the impact of the piece is emotionally strong

and not just rational, this desire will appear.