A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: Is your performance, though, a little more authoritative?

BD: Is your performance, though, a little more authoritative? MS: Oh, sure, maybe because I work a lot of years

— more than ten years, actually — in radio.

I receive a habit to feel in the studio like in the concert hall. But

I remember in the beginning of my work in radio, it was a little bit difficult

for me.

MS: Oh, sure, maybe because I work a lot of years

— more than ten years, actually — in radio.

I receive a habit to feel in the studio like in the concert hall. But

I remember in the beginning of my work in radio, it was a little bit difficult

for me.  MS: Yeah. Absolutely.

MS: Yeah. Absolutely.

MS: It's really difficult to do it during performance, but at

rehearsals, musicians are so professional! Immediately, during just

a few minutes — maybe ten, 20 minutes —

they actually understand your way. It's like when you meet

some person you know and this person starts to talk, you recognize his voice

very fast. You feel the character because you are professional!

We are all professional in relation with people, but musicians are professional

in question of relation with musicians. They catch very fast your ideas,

and if the orchestra is better, they do it faster. They catch your

ideas and they have a strong memory. It comes with the experience of

a conductor. When you are young, it is more difficult, but later your

experience helps you grow up, and it becomes easier to establish good professional

relations with a new orchestra. Actually, in the conductor's business,

the most important thing is relations with people; human relations because

each musician is a human being and he has a character. You immediately

recognize his character and what's closer to his heart through his solos.

For example, even if you never talk with the principal clarinet, you feel

his character and his personality after he plays his solo in the symphony.

And when he approaches and starts to talk with you, you feel like you have

met him and talked with him before.

MS: It's really difficult to do it during performance, but at

rehearsals, musicians are so professional! Immediately, during just

a few minutes — maybe ten, 20 minutes —

they actually understand your way. It's like when you meet

some person you know and this person starts to talk, you recognize his voice

very fast. You feel the character because you are professional!

We are all professional in relation with people, but musicians are professional

in question of relation with musicians. They catch very fast your ideas,

and if the orchestra is better, they do it faster. They catch your

ideas and they have a strong memory. It comes with the experience of

a conductor. When you are young, it is more difficult, but later your

experience helps you grow up, and it becomes easier to establish good professional

relations with a new orchestra. Actually, in the conductor's business,

the most important thing is relations with people; human relations because

each musician is a human being and he has a character. You immediately

recognize his character and what's closer to his heart through his solos.

For example, even if you never talk with the principal clarinet, you feel

his character and his personality after he plays his solo in the symphony.

And when he approaches and starts to talk with you, you feel like you have

met him and talked with him before.  MS: Some of his symphonies are very long and difficult.

Sometimes not all orchestras are able enough to perform these symphonies.

Also, as I said, chamber music in our time is maybe less popular than symphonic

music, but it goes up all the time. It's hard to say; I like all of

my father's music.

MS: Some of his symphonies are very long and difficult.

Sometimes not all orchestras are able enough to perform these symphonies.

Also, as I said, chamber music in our time is maybe less popular than symphonic

music, but it goes up all the time. It's hard to say; I like all of

my father's music.|

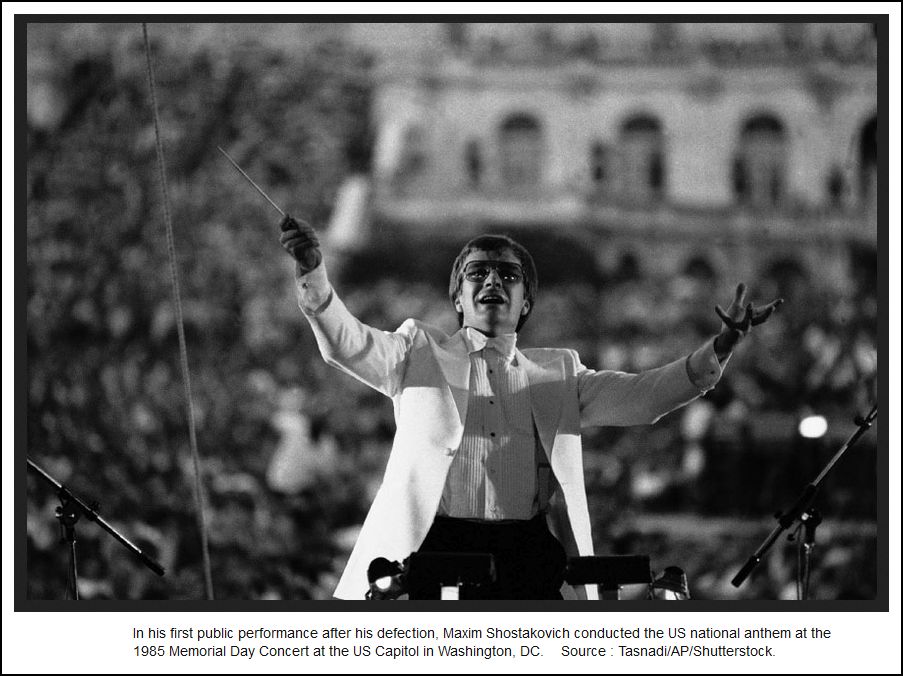

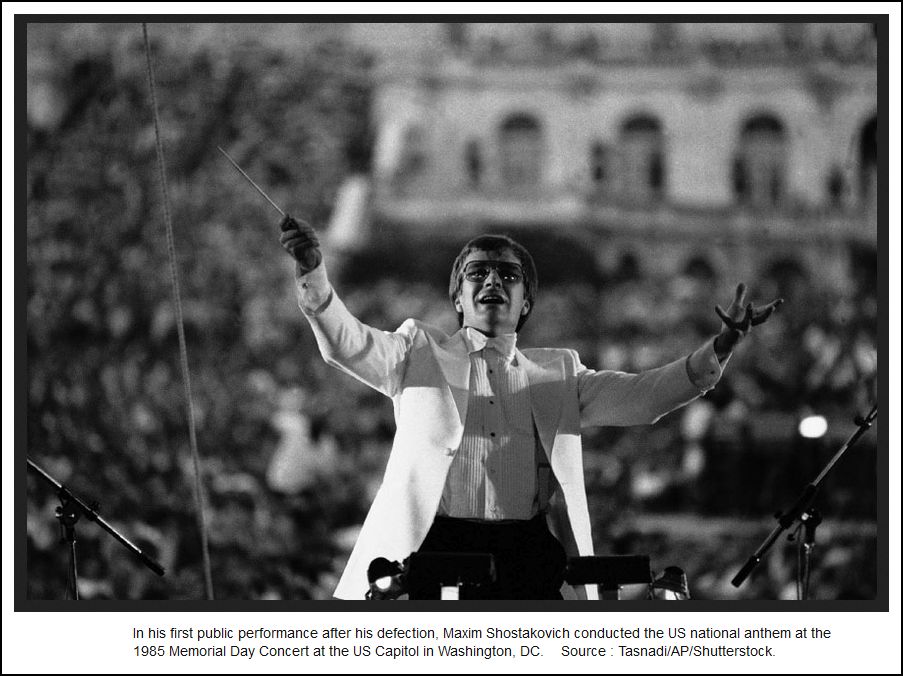

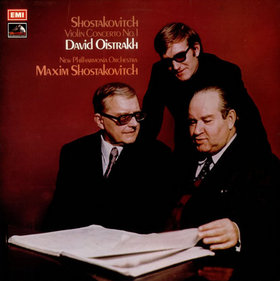

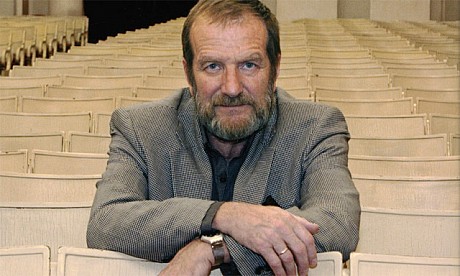

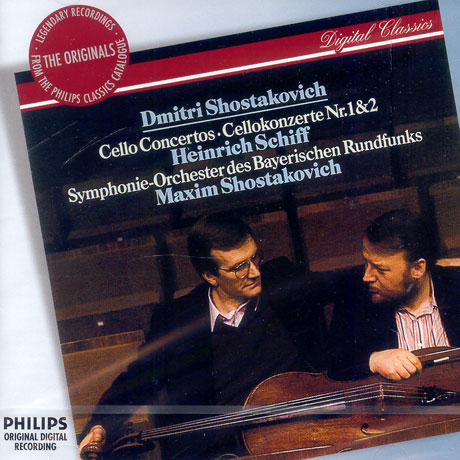

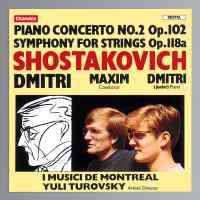

Maxim Shostakovich

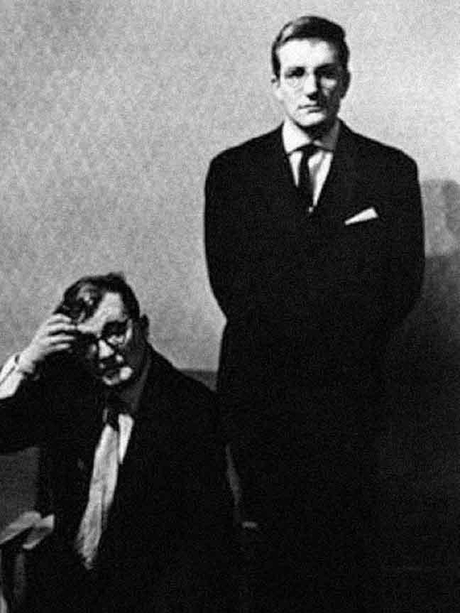

Son of the composer Dmitri Shostakovich, Maxim Shostakovich was born in 1938 in Leningrad. He studied piano at the Moscow Conservatoire with Yakov Flier and conducting with Gennady Rozhdestvensky and Igor Markevich. In 1971 he was appointed Principal Conductor and Artistic Director of the USSR Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra, with which he toured worldwide including Western Europe, Japan and the United States and premiered many important works, including his father’s Symphony No. 15 at the Moscow Conservatoire on January 1st 1972. In 1979 he conducted his father’s opera The Nose at the English National Opera.

Maxim Shostakovich has conducted the major orchestras throughout the whole world, in America he has for instance worked with: the New York Philharmonic, Washington National Symphony, the Orchestras of Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Atlanta, Toronto, Ottawa, Vancouver, Calgary, San Diego, Dallas, Houston and others.  In the years 1986-1991 he was the Music Director of the New Orleans Symphony

Orchestra. He has appeared with the Hong Kong Philharmonic as Principal Guest

Conductor, with the Seoul Philharmonic, the Yomiuri Nippon Orchestra, the

Symphony orchestras of the New Zealand and Jerusalem, the Kyoto Symphony,

the Osaka Philharmonic, the Sapporo Symphony Orchestra and the New Japan

Philharmonic. He has conducted extensively in Europe. In Germany he has worked

with the Bayerischer Rundfunk, Beethovenhalle Orchestra of Bonn, Dortmund

Philharmonic and with the Hamburg Staatsoper for the Yuri Lyubimov´s

production of D.Shostakovich´s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.

In the years 1986-1991 he was the Music Director of the New Orleans Symphony

Orchestra. He has appeared with the Hong Kong Philharmonic as Principal Guest

Conductor, with the Seoul Philharmonic, the Yomiuri Nippon Orchestra, the

Symphony orchestras of the New Zealand and Jerusalem, the Kyoto Symphony,

the Osaka Philharmonic, the Sapporo Symphony Orchestra and the New Japan

Philharmonic. He has conducted extensively in Europe. In Germany he has worked

with the Bayerischer Rundfunk, Beethovenhalle Orchestra of Bonn, Dortmund

Philharmonic and with the Hamburg Staatsoper for the Yuri Lyubimov´s

production of D.Shostakovich´s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.Maestro Shostakovich also conducted in England with the London Symphony, City of Birmingham Symphony and Royal Liverpool Philharmonic. In Sweden he worked with the Symphony orchestras of Malmö, Helsingborg, Norrköping and with the Göteborg Symphony. He made a production of Lady Mcbeth of Mtsensk at the Royal Opera in Stockholm. In Norway he conducted the Trondheim Symphony, in Switzerland with the Tonhalle Orchestra of Zürich, in Italy with the Orchestra Della Toscana in Florence and the Santa Cecilia Academy in Rome and in France with the Orchestre de Lille and Orchestre du Capitole in Toulouse. He also worked with the Rotterdam Philharmonic. Mr Shostakovich made his North America opera debut conducting D.Shostakovich´s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk at the Juilliard School. In January 1984 he led the production of Tchaiikovsky´s Eugene Onegin at the Washington Opera to critical acclaim. Maestro Shostakovich conducts regularly at the famous St. Petersburg White Nights Festival. Mr Shostakovich records for labels Teldec, Koch/Schwann, Angel, Philips Records and Chandos. He has been involved in an ongoing project in collaboration with Supraphon, recording his father’s symphonies with the Prague Symphony Orchestra. Mr Shostakovich is a doctor of Arts of the Maryland University. Text of biography from Columbia Artists

Management Inc --

|

This interview was recorded in Chicago on July 10, 1992, while he

was engaged to conduct at the Grant Park Music Festival. Portions were

used on WNIB (along with musical

examples) in 1993 and again in 1998. It was used again on both WNUR and Contemporary Classical Internet Radio

in September, 2006. The transcription was made in 2011 and posted on

this website in September of that year.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.