A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

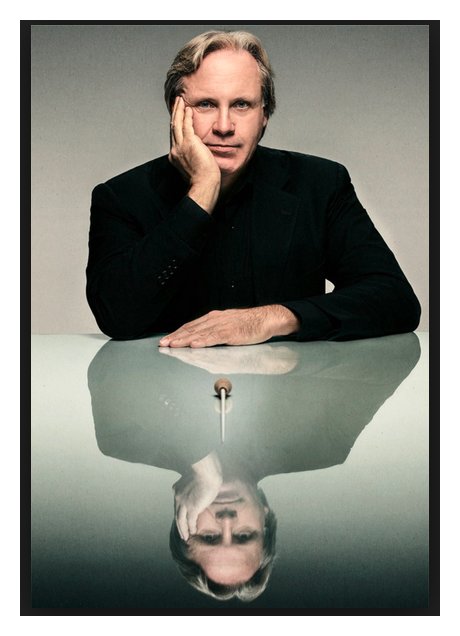

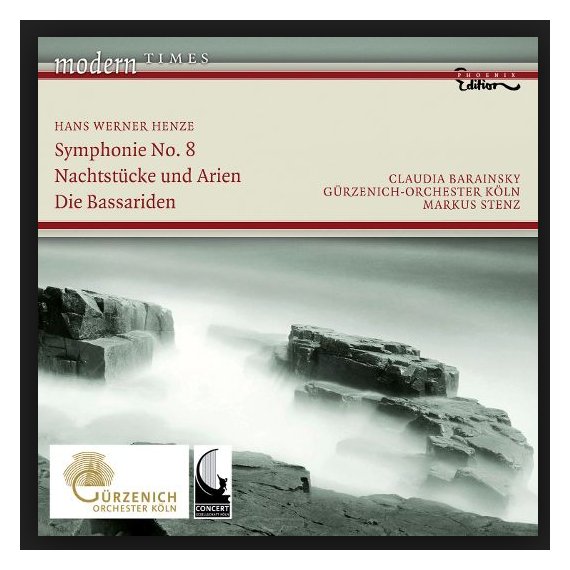

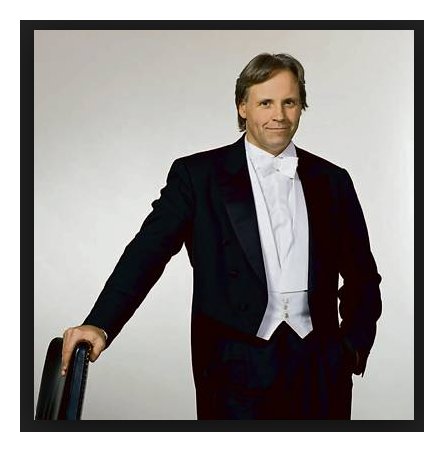

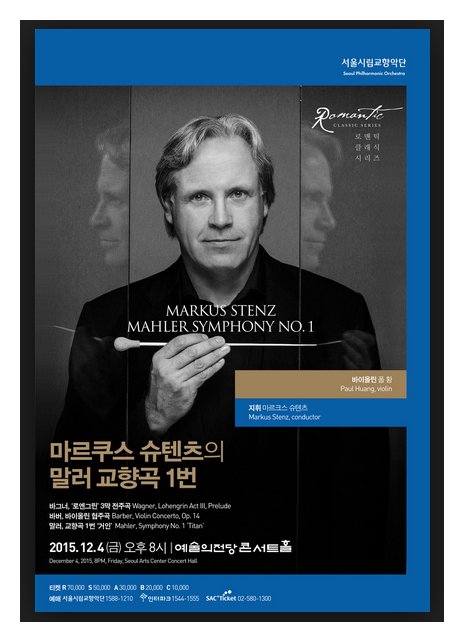

| Markus Stenz (Conductor) Born 28 February 1965, Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler, Rhineland-Palatinate The German conductor, Markus Stenz, studied at the Hochschule für Musik in Köln bei Volker Wangenheim and had a scholarship in Tanglewood for instruction with Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa. Stenz directed the Cantiere Internazionale d'Arte in Montepulciano from 1989 to 1995, and was the principal conductor of the London Sinfonietta, the most renowned British ensemble for contemporary music, from 1994 to 1998. In 1998 he was appointed as the artistic director and principal conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. After intensive work in Australia and the USA, the sought-after conductor recently concentrated his world-wide activities again on Europe. Stenz was Principal Conductor of the Gürzenich Orchestra (Gürzenich-Kapellmeister) from 2003 to 2014. During his tenure, beginning in October 2005, concerts of the Gürzenich Orchestra are recorded live on their own label "GO live!" and made available within 5 minutes of the end of the concert the same night for purchase by audience members. On the concert podiums Markus Stenz led such renowned orchestras as the Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Tonhalle Orchester Zürich, Münchner Philharmoniker, Staatskapelle Berlin, Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg, Bayerischer Rundfunk Symphonieorchester, WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln, NDR Sinfonieorchester Hamburg, Ensemble Modern and Ensemble Intercontemporain. Also in Scandinavia, he conducted major orchestras such as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Philharmonischen Orchester Helsinki and Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra. In the USA he worked with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Minnesota Orchestra, Houston Symphony Orchestra and Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Among the productions, which Markus Stenz conducted as an opera conductor, are Mozart's Don Giovanni for the English National Opera and Le nozze di Figaro in Los Angeles, Gioacchino Rossini's Il Turco in Italia at the Stadttheater Basel, Kurt Weill's Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny at the Staatstheater Stuttgart, Hans Zender's Stephen Climax, Alexander von Zemlinsky's Der Zwerg and Eine florentinische Tragödie at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, Igor Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress at the San Francisco Opera, as well as the highly-esteemed production of Wolfgang Rihm's Die Eroberung von Mexiko at the Oper in Frankfurt. In the summer of 2004 he made a successful debut with Leoš Janáček's Jenůfa at the Glyndebourne Festival. After his debut at the Kölner Oper with L.v. Beethoven's Fidelio, he had successes in 2004-2005 season with Richard Strauss' Salome, the Köln's premiere of Detlev Glanert's Scherz, Satire, Ironie und tiefere Bedeutung, as well as Mozart's Idomeneo. In the following season he conducted on Hans Werner Henze's Die Bassariden, Engelbert Humperdinck's Hänsel und Gretel, the premiere of Jan Müller-Wieland's Der Held der westlichen Welt, as well as Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. Markus Stenz has a special affinity to the music of Hans Werner Henze. In 1990 he conducted the premiere performance of Das verratene Meer at the Deutschen Oper Berlin and the Italian premiere of this work at the Teatro de La Scala in Milan, as well as the American premiere of at the San Francisco Opera. In 1997 he conducted the premiere performance of Venus und Adonis at the Bayerischen Staatsoper München. In addition came the performances of Die englische Katze (Hebbel-Theater Berlin), Elegie für junge Liebende (La Fenice, Venice) and Die Bassariden (Staatsoper Hamburg). In summer 2003 he conducted at the Salzburg Festival a perfrmance of Henze's L'Upupa und der Triumph der Sohnesliebe with the Wiener Philharmoniker. Stenz made his debut at the Kölner Philharmonie in 1996 with the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln. In February 2000 he directed a concert of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra there, in September 2002 the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie. In June 2001 he made his debut with the Gürzenich-Orchester Köln. |

BD: So he’s hovering there a little bit?

BD: So he’s hovering there a little bit? MS: Yes, particularly in Schumann’s case I have

to say that the scoring is very idealistic. If anything, Schumann’s

Second Symphony for me stands for

the principle of idealism. You can always trace the idea behind it.

You always can trace the principal musical line and the principal statement

on every given page of the score, but sometimes the orchestration blurs that.

Sometimes the way he uses the dynamics doesn’t make the principal line stand

out as clearly as you might want it to. So being amongst contemporary

composers, and seeing how they fight for the best way of notating things,

and seeing how they actually do establish principal lines first and then

do a little embellishment here or there, just to see how they go about creating

a piece makes it easier to look at the existing scores and do the reverse

process.

MS: Yes, particularly in Schumann’s case I have

to say that the scoring is very idealistic. If anything, Schumann’s

Second Symphony for me stands for

the principle of idealism. You can always trace the idea behind it.

You always can trace the principal musical line and the principal statement

on every given page of the score, but sometimes the orchestration blurs that.

Sometimes the way he uses the dynamics doesn’t make the principal line stand

out as clearly as you might want it to. So being amongst contemporary

composers, and seeing how they fight for the best way of notating things,

and seeing how they actually do establish principal lines first and then

do a little embellishment here or there, just to see how they go about creating

a piece makes it easier to look at the existing scores and do the reverse

process. BD: You’re Music Director in a couple of different

places, and that’s a completely different thing from guest conducting.

But in one place or the other, how do you select from this huge body of music

what you’re going to conduct and what you’re going to learn?

BD: You’re Music Director in a couple of different

places, and that’s a completely different thing from guest conducting.

But in one place or the other, how do you select from this huge body of music

what you’re going to conduct and what you’re going to learn? MS: A fascinating thing about opera is that so many

art forms come together there. However, there are so many elements,

so there’s so many possibilities for disaster. Anything can go wrong

at any time, and so most of the time opera performances do go wrong, and

you won’t get out of an evening what you’d love to hear. But every

once in a while there is this glorious evening where everything falls into

place, and then opera is just unbeatable and irresistible.

MS: A fascinating thing about opera is that so many

art forms come together there. However, there are so many elements,

so there’s so many possibilities for disaster. Anything can go wrong

at any time, and so most of the time opera performances do go wrong, and

you won’t get out of an evening what you’d love to hear. But every

once in a while there is this glorious evening where everything falls into

place, and then opera is just unbeatable and irresistible. MS: No, we all have our individual tastes, and that’s

a very good thing. Music is universal and very versatile, and it’s

for everybody to make their own choice. So it is not for everybody,

no.

MS: No, we all have our individual tastes, and that’s

a very good thing. Music is universal and very versatile, and it’s

for everybody to make their own choice. So it is not for everybody,

no.

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in the newly-renovated office suite

of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on November 10, 1997. Portions were

broadcast on WNIB on three separate occasions during the year 2000.

This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.