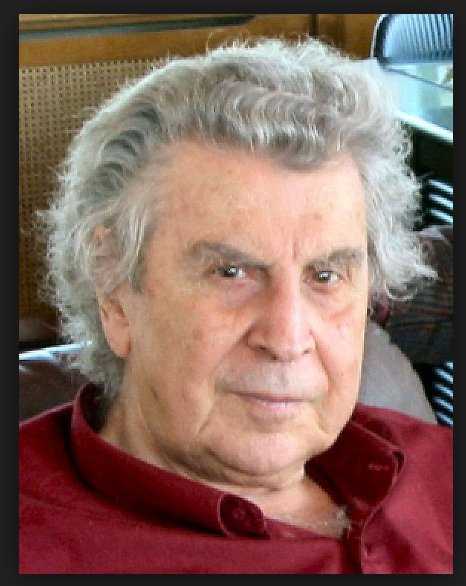

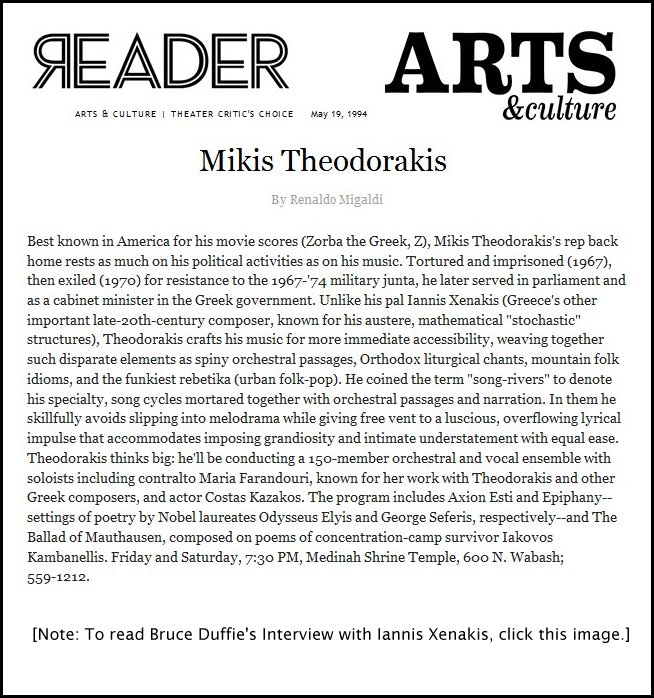

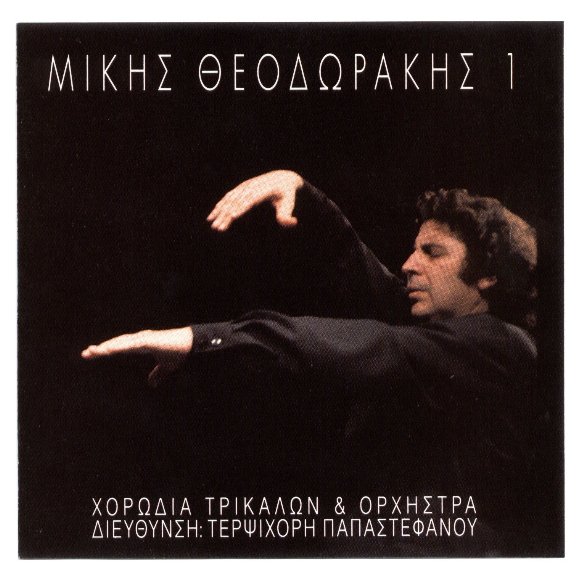

The Greek Consul in Chicago was giving a

party for the composer [see photo

above] who was in the Windy City to conduct a performance of

some of his large works. [See

news item at right.] Our appointment was just before the

gathering so that we could spend a few minutes discussing his ideas,

his experiences, and his outlook.

The Greek Consul in Chicago was giving a

party for the composer [see photo

above] who was in the Windy City to conduct a performance of

some of his large works. [See

news item at right.] Our appointment was just before the

gathering so that we could spend a few minutes discussing his ideas,

his experiences, and his outlook. BD: If a film is

offered to you, how do you decide if

you will say, “Yes, I will write the music,” or, “No, I don’t want to

be involved with that film?”

BD: If a film is

offered to you, how do you decide if

you will say, “Yes, I will write the music,” or, “No, I don’t want to

be involved with that film?” MT: Future for me

is the human being. I think

that the man is the same, essentially same. We have the same

passions, the

same problems, the same questions, the same

anxieties, everything. And I think the man is Romantic all the

time. Man is like a child; he is afraid, very

afraid. It’s exactly the same everywhere. I think the man

wants peace,

the love, he likes the family, likes the children, likes the all the

animals,

the birds, the country, the colors. Man is the same in our

concept of this, in all the cultures. We all have the same

problems. I think the problem for the man is how to live in

harmony with the others, with the nature, with the time, to take joys

for his life, for the little things like the wine, the love, the

friendship. It is very important, the little things. And

after, the big

problem is the death. The death is not accepted by us. We

won’t

accept it. We will not accept that tomorrow, perhaps after an

accident, must be nothing. But it’s impossible to be

nothing. The death is impossible, and for this

reason I think the man is the only animal who wants to be immortal, to

fight the death.

MT: Future for me

is the human being. I think

that the man is the same, essentially same. We have the same

passions, the

same problems, the same questions, the same

anxieties, everything. And I think the man is Romantic all the

time. Man is like a child; he is afraid, very

afraid. It’s exactly the same everywhere. I think the man

wants peace,

the love, he likes the family, likes the children, likes the all the

animals,

the birds, the country, the colors. Man is the same in our

concept of this, in all the cultures. We all have the same

problems. I think the problem for the man is how to live in

harmony with the others, with the nature, with the time, to take joys

for his life, for the little things like the wine, the love, the

friendship. It is very important, the little things. And

after, the big

problem is the death. The death is not accepted by us. We

won’t

accept it. We will not accept that tomorrow, perhaps after an

accident, must be nothing. But it’s impossible to be

nothing. The death is impossible, and for this

reason I think the man is the only animal who wants to be immortal, to

fight the death.

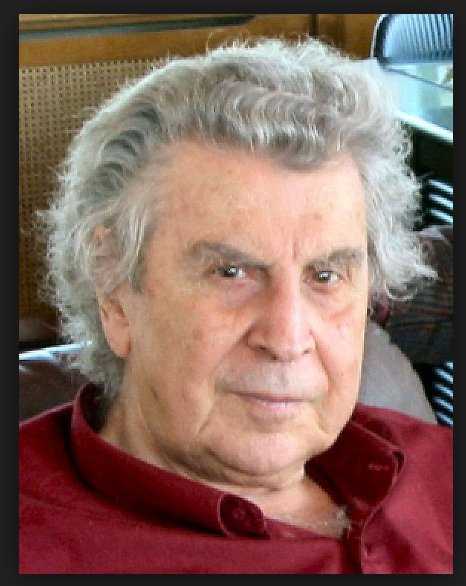

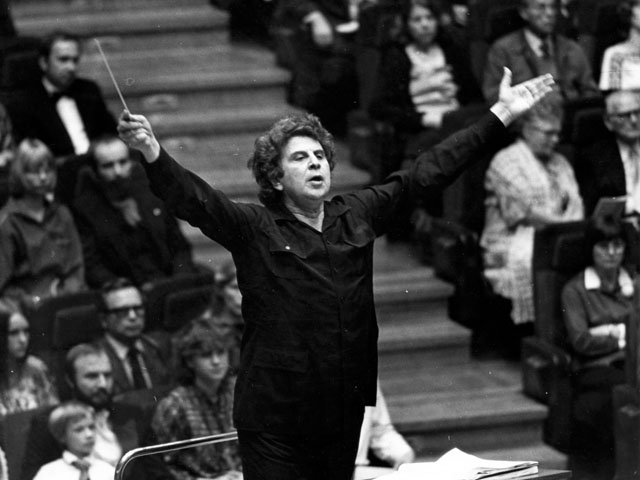

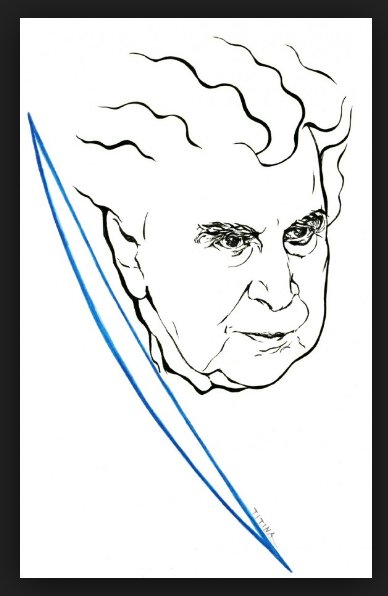

Mikis Theodorakis was born on

the Greek island of Khios in the Aegean Sea on 29 July 1925. He grew up

with Greek folk music and was early influenced by the Byzantine

liturgy. Even as a child, he decided to become a composer. Theodorakis’ life has been characterized by his political

commitment to the Greek people and their freedom, by persecution and

struggle for survival. His activities as resistance fighter during the

occupation of Greece by German, Bulgarian and Italian troops led to his

arrest and torture in 1943. The Civil War of 1947-49 to him meant being

tortured again and finally banished to the penal colonies of Ikaria and

Makronissos, where he barely survived. Theodorakis’ life has been characterized by his political

commitment to the Greek people and their freedom, by persecution and

struggle for survival. His activities as resistance fighter during the

occupation of Greece by German, Bulgarian and Italian troops led to his

arrest and torture in 1943. The Civil War of 1947-49 to him meant being

tortured again and finally banished to the penal colonies of Ikaria and

Makronissos, where he barely survived.From 1945 Theodorakis studied intermittently with Philoktitis Economidis at the Odeion music school and from 1954-1959 with Eugène Bigot and Olivier Messiaen at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1957 he was awarded the gold medal of the composition competition of the World Festival in Moscow for his ’Suite No.1’ and in 1959 the American Copley Prize for the best European composer. Furthermore he received the first prize of the International Institute of Music in London. During that time, he created ballet musics such as Greek Carnival, Les Amants de Téruel and Antigone in close collaboration with international theatres. This successful period was interrupted by a bitter cultural struggle in Greece in which right-wing and left-wing groups and factions were engaged in fierce controversies. Theodorakis became one of the leading personalities among the renewers of Greece. After the assassination of the left-wing politician Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963 he founded the Lambrakis Youth and took his seat in the Greek Parliament. During that time, he also notched up great successes and achieved worldwide fame with compositions such as the film music Zorba the Greek and the oratorio Axion Esti. The internal political disturbances of the following years led to the formation of a big and a small junta and their coup d’état. Theodorakis founded the underground movement ’Patriotic Front’. Shortly afterwards, his music was banned, and he was arrested and imprisoned in the concentration camp of Oropos. He was released in 1970 in response to an international initiative of important artists such as Dmitri Shostakovich, Hanns Eisler and Leonard Bernstein. Having become a symbol of the European student movement, not least by Zorba the Greek, Theodorakis started to live in exile in Paris from 1970. At concert tours he called for further resistance to the military dictatorship and for the restoration of democracy in his home country where he could return to as a politician in 1974. At that time, his compositional work focussed mainly on numerous large-scale song cycles. It was not until the beginning of the 1980s that he moved back to Paris and fully resumed composing. He began to create increasingly symphonic works, cantatas, oratorios such as Canto General on the occasion of the accession of Greece to the EC, sacred music and operas such as I Metamorfosis tou Dionisou. In the time that followed, the independent left-winger Mikis Theodorakis was appointed Minister without Portfolio in the Conservative government of Mitsotakis, making an educational and cultural reform his particular task from 1990 till 1992 and promoting the reconciliation between Greece and Turkey. After retreating from politics, he was appointed general music director of the Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of the Hellenic Radio and Television in 1993 and was also in great demand as conductor of his own works. In the years before and after 1990 Theodorakis composed the great lyric tragedies based on classical literature: Medea, Elektra, Antigone. At the beginning of 1998 he donated his entire collections to the Lilian Voudouri Foundation at the Megaron in Athens. In 2000 Mikis Theodorakis was proposed as nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize with great support of not only the Greek population and was shortlisted by the Nobel Committee. For his artistic œuvre in the field of film music he has been awarded the Erich Wolfgang Korngold Prize at the International Film Music Biennial in Bonn in 2002. In November 2005 Theodorakis has been awarded the UNESCO prize for arts and music in Aachen/Germany. -- Text from the Schott

Website

|

This interview was recorded at the home of the Greek Consul in

Chicago on May

19, 1994. Portions

(along with recordings) were used on WNIB the following year, and again

in 2000. The transcription was made and posted

on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.