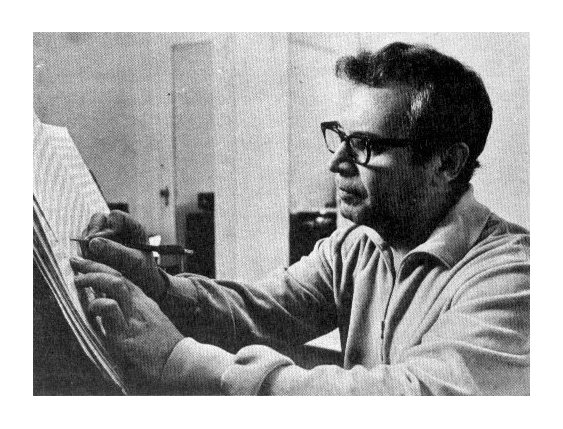

Lester Trimble:

Yes. It was a very nice thing. I was in the Air Force at

that time, and I got very sick out in Salt Lake City. So they

shipped me over to Tucson, Arizona, to be in a hospital, where I was

for a long time. I had been composing since I was about sixteen,

and before I went into the service I had finished a string

quartet. Somehow being out there in Arizona, I suddenly felt as

if I was just next door to California. That’s my sense of

geography for you. [Both laugh] I got the idea of writing

to Schoenberg and asking him if he thought I ought to seriously think

about a career in composing. Up to that time I had been a

violinist, and I had wanted to compose, but I didn’t know. I

hadn’t studied with anybody. So, I wrote to him, and I waited for

several months and thought that I would never hear, and then finally, a

letter did come. He said, “Send me something.” He had been

sick, and that’s why it took so long. So I wrote home and asked

them to send the one copy that existed of my string quartet that I had

completed. That was long before the days of Xerox, so that was

the only copy that existed. I sent it to him, and then I got a

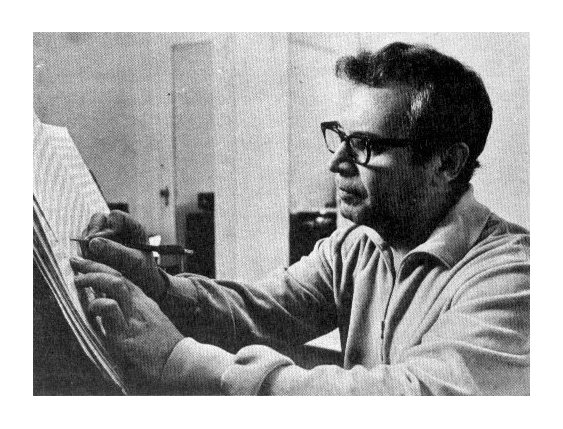

very nice letter back from him —

which was later printed after his death in the letters that

were collected and published [shown at left] — commenting

on it. Obviously he felt I should continue to compose, and

suggested that after the war was over I come out and study with him.

Lester Trimble:

Yes. It was a very nice thing. I was in the Air Force at

that time, and I got very sick out in Salt Lake City. So they

shipped me over to Tucson, Arizona, to be in a hospital, where I was

for a long time. I had been composing since I was about sixteen,

and before I went into the service I had finished a string

quartet. Somehow being out there in Arizona, I suddenly felt as

if I was just next door to California. That’s my sense of

geography for you. [Both laugh] I got the idea of writing

to Schoenberg and asking him if he thought I ought to seriously think

about a career in composing. Up to that time I had been a

violinist, and I had wanted to compose, but I didn’t know. I

hadn’t studied with anybody. So, I wrote to him, and I waited for

several months and thought that I would never hear, and then finally, a

letter did come. He said, “Send me something.” He had been

sick, and that’s why it took so long. So I wrote home and asked

them to send the one copy that existed of my string quartet that I had

completed. That was long before the days of Xerox, so that was

the only copy that existed. I sent it to him, and then I got a

very nice letter back from him —

which was later printed after his death in the letters that

were collected and published [shown at left] — commenting

on it. Obviously he felt I should continue to compose, and

suggested that after the war was over I come out and study with him. BD: How is the

level of criticism today?

BD: How is the

level of criticism today? BD: What do you as

a composer expect of the public?

BD: What do you as

a composer expect of the public? LT: It has to be

learned intuitively by each young composer. It cannot be taught

in an intellectual sense. Though some teachers try to

do it, you cannot say to a student, “Now, you must do this in this

way,” because if you do that, you freeze up and stultify the creativity

of the student. But if you’re willing to fatigue yourself quite a

bit in the process, you can project into their ideas and help them to

bring them to full blossom. That, in a way, ends up being a kind

of a teaching process, because you can guide them without necessarily

pushing them too hard in any one direction, stylistically.

LT: It has to be

learned intuitively by each young composer. It cannot be taught

in an intellectual sense. Though some teachers try to

do it, you cannot say to a student, “Now, you must do this in this

way,” because if you do that, you freeze up and stultify the creativity

of the student. But if you’re willing to fatigue yourself quite a

bit in the process, you can project into their ideas and help them to

bring them to full blossom. That, in a way, ends up being a kind

of a teaching process, because you can guide them without necessarily

pushing them too hard in any one direction, stylistically.

BD: Do you feel

that you are at the mercy of the performer or the conductor?

BD: Do you feel

that you are at the mercy of the performer or the conductor?LESTER TRIMBLE, A COMPOSER, CRITIC AND

TEACHER, DIES AT 63

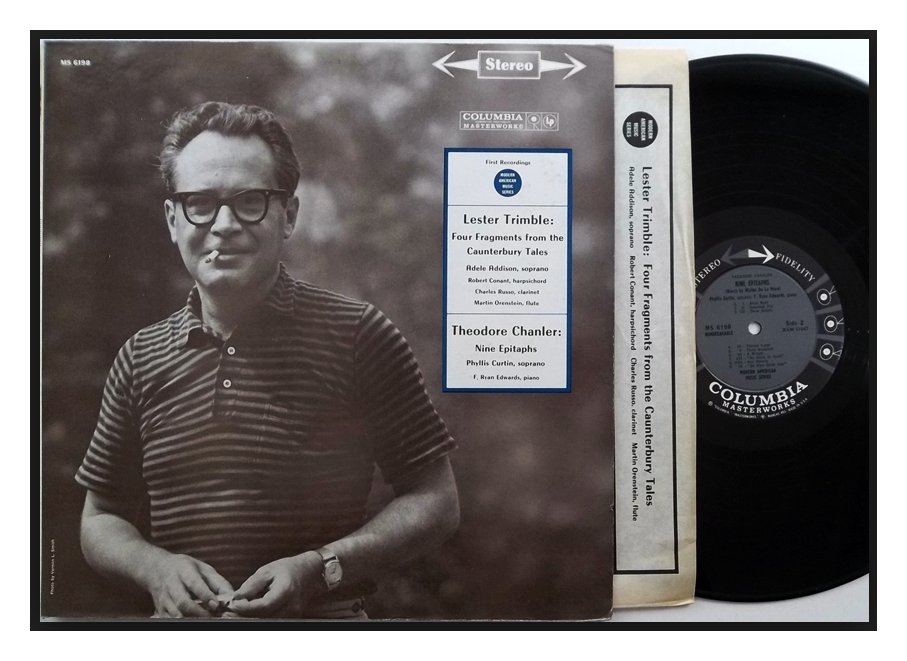

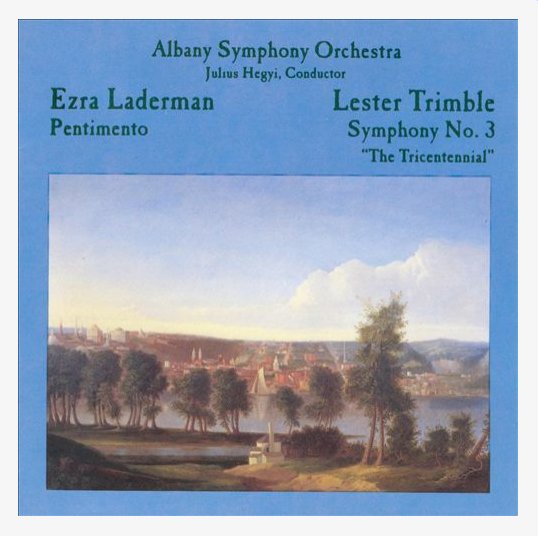

By EDWIN McDOWELL Published in The New York Times, January 2, 1987 Lester Trimble, a composer, critic and music teacher, died Wednesday afternoon [December 31, 1986] of heart failure. The 63-year-old composer, who had had a heart condition, collapsed shortly after noon in a restaurant on Broadway and was dead on arrival at Roosevelt Hospital. Mr. Trimble composed symphonies, chamber works, operas and songs. He received honors and commissions from symphony orchestras, foundations and music societies. Mr. Trimble's Symphony No. 3, ''The Tricentennial,'' commissioned for the City of Albany's 300th year, was given its premier performance last September by the Albany Symphony Orchestra. Last January he received an honorary doctorate from St. John's University at its commencement, for which he composed the processional music. Among his best-known compositions are his Second Symphony (1968), which is based entirely on elements from a single lyrical theme, and a series of works he called ''panels,'' which are for diverse instrumental ensembles. Trained at Carnegie Tech Born in Bangor, Wis., on Aug. 29, 1923, Mr. Trimble's musical training was acquired largely at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. After service in the United States Army, he studied at Tanglewood, where he met Darius Milhaud, with whom he subsequently studied in Paris. 'A Richer Melodic Gift' Settling in New York after returning from Paris in 1952, he was the music critic of The Nation, a music reviewer for The New York Herald-Tribune, managing editor of Musical America and executive director of the American Music Center. He was professor of composition at the University of Maryland from 1963-68 and composer in residence with the New York Philharmonic from 1967-68, and he joined the Juilliard School faculty in 1971. In 1973 he became the first composer in residence at Wolf Trap Farm Park. He taught privately the past two years. Writing of the composer's String Quartet No. 1 in 1955, a New York Times critic wrote, ''He has a richer melodic gift than most, a delight in complex and vigorous rhythms, the ability to invent new sonorities without striving for far-fetched effects and considerable emotional intensity.'' After a program at Town Hall in 1962 that covered a dozen years of Mr. Trimble's music, another Times critic wrote that all the works revealed some major virtues in common: ''a wide-ranging, seemingly inexhaustible melodic invention; intricate rhythmic patterns; an imaginative feeling for instrumental and vocal color.'' Mr. Trimble is survived by his wife, Constance Wilhelm, of Manhattan, and a brother, John R., of Massapequa. Funeral services are private, and a memorial service will be announced. |

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

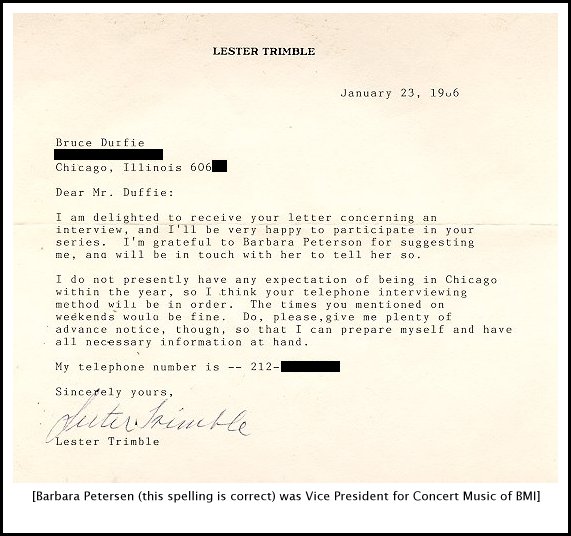

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on March 22,

1986. Portions were broadcast (along with recordings) on WNIB

later that year, and again in 1987, 1988, 1993, and 1998.

This transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2014.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.