A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: That was in four

acts?

BD: That was in four

acts? BD: So how did you

decide which roles you would accept, and which roles you would decline?

BD: So how did you

decide which roles you would accept, and which roles you would decline? BD: Do you wish you

had made the recording of Budd?

BD: Do you wish you

had made the recording of Budd? BD: If you are the

character onstage, then when

do you lose the character — when you walk off

stage, when you’re

back in the dressing room, when you’re back home, the next day?

How long does it take to become Theodor Uppman again?

BD: If you are the

character onstage, then when

do you lose the character — when you walk off

stage, when you’re

back in the dressing room, when you’re back home, the next day?

How long does it take to become Theodor Uppman again? BD: Do you think

opera works well

in translation?

BD: Do you think

opera works well

in translation? BD: Then why did she

want to be an opera singer?

BD: Then why did she

want to be an opera singer?|

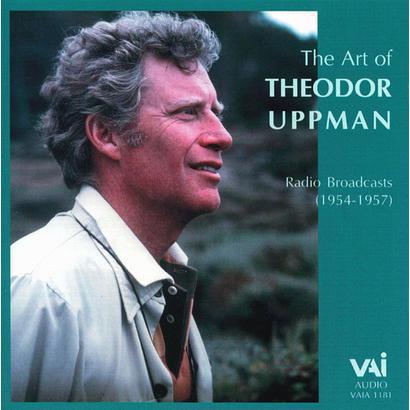

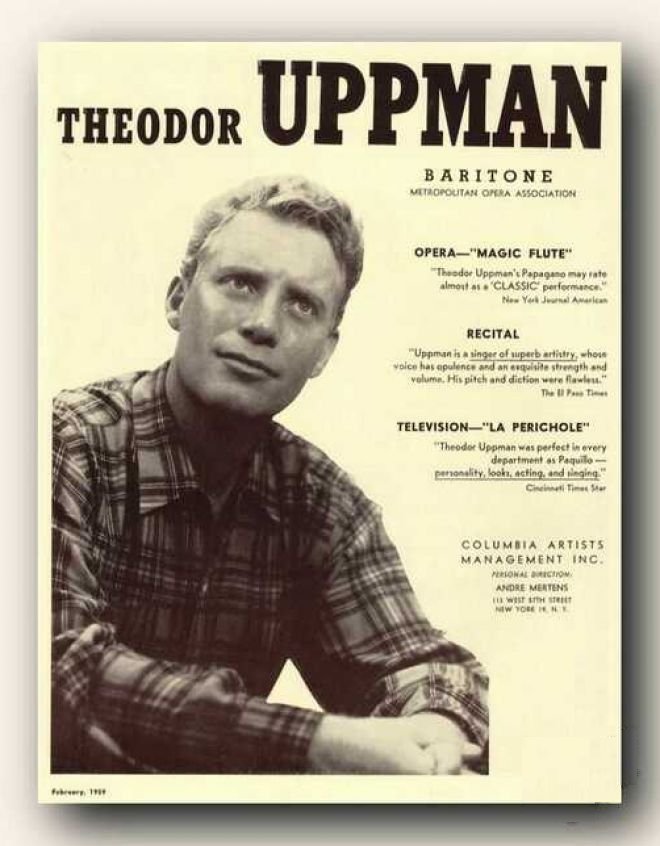

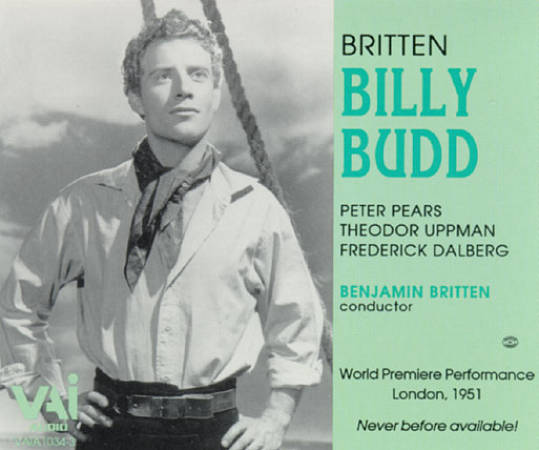

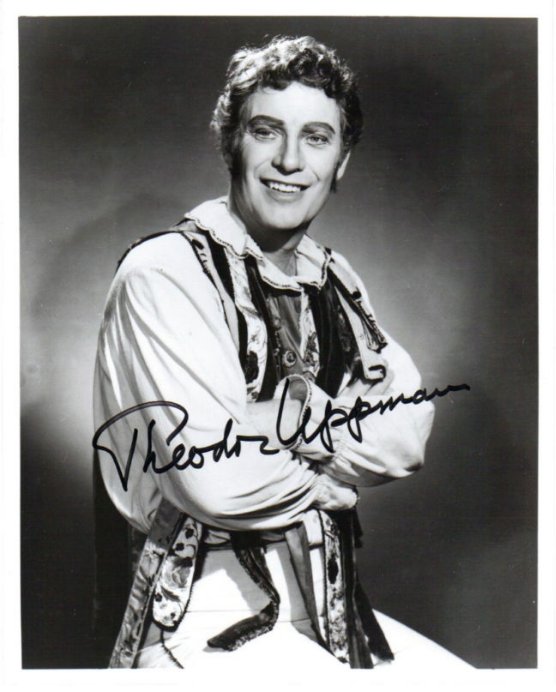

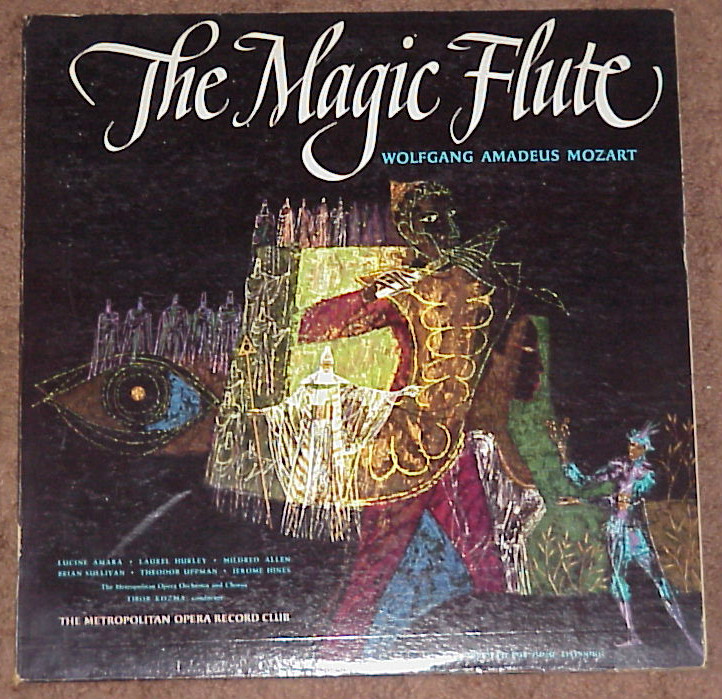

Theodor Uppman

By Alan Blyth The Guardian, Monday 21 March 2005 19.03 EST Although the baritone Theodor Uppman, who has died aged 85, will always be recalled in this country as the creator of the title role in Billy Budd, at Covent Garden in 1951, he was renowned in his American homeland for a wide variety of parts, all suited to his handsome presence and attractive voice. These included the name role in Carlisle Floyd's Passion Of Jonathan Wade (New York City Opera, 1962) and Bill in Leonard Bernstein's A Quiet Place (Houston Opera, 1983). Benjamin Britten originally conceived the part of Budd for Geraint Evans, then at the threshold of a distinguished career, but Evans - primarily a bass-baritone - found the tessitura of the part too high, and was assigned the role of Mr Flint. Uppman, whose career seemed to have stalled after a promising start, had worked with Alfred Drake on a Broadway musical. When it became known that David Webster, then general administrator at Covent Garden, was in New York auditioning for a Billy Budd, he persuaded Uppman to enter the fray. Turning up at the audition, tanned and blond, Uppman seemed ideal material. His voice was taped and the results were taken back to Britten with a strong recommendation from Webster. He got the job, and Britten was delighted. His ideal for the role - a baritone who was youthful, enthusiastic and innocent-looking - had been completely fulfilled. The critics praised Uppman as much as the opera itself. I recall how fresh and spontaneous an interpreter he proved to be. His looks and mellow, yet virile, tone, allied to a seemingly natural gift for portraying a strong, yet still boyish sailor, were unforgettable attributes, and he made his solo, when condemned to death, as eloquent as it should be. Soon afterwards, he took the part at the first American performances, on television, and he went on to sing it elsewhere until 1970. Latterly, he coached other baritones in the part, notably Simon Keenlyside. He soon formed a connection with Aldeburgh, and taught until recently at the Britten-Pears School at Snape, of which he became an honorary director. Uppman was born in San Jose, California, to a family of Swedish heritage. He studied at the Curtis Institute, Philadelphia (1939-41), moved on to opera workshops at Stanford University (1941-42) and the University of Southern California (1948-50). He first sang in concert in 1941, but his real debut came in 1947, as Pelléas in a concert account of Debussy's opera with the San Francisco Opera. His partner was Maggie Teyte, the eminent interpreter of Mélisande. This was the role of Uppman's debut the following year at the New York City Opera, and for his first appearance at the Metropolitan, in 1953. Later, he also proved, at the Metropolitan, a perfect Papageno, with Bruno Walter suggesting that he was not just singing, but also being, the part. Uppman went on to sing some 400 performances of 15 parts at the Met, though seldom anything heavier than Mozart, or Sharpless in Madama Butterfly. He was particularly admired as Harlequin, in Richard Strauss's Ariadne Auf Naxos, and Eisenstein, in Johann Strauss's Die Fledermaus. A late appearance was as the seven mysterious baritone figures in Britten's Death In Venice, at the Geneva Opera. He taught until recently at the Manhattan School of Music. Not long ago, a set of recordings was issued of the premiere of Billy Budd. It is aural proof that the original verdicts of his supremacy in the role were not exaggerated. He is survived by his wife Jean, whom he married in 1943, and their two children. · Theodor Uppman, baritone, born January 12 1920; died March 17, 2005 |

This interview was recorded at Mr. Uppman’s

apartment in New York City on March 22, 1988. Sections

were used (along with

recordings) on WNIB later that year, and again in 1990, 1995 and 2000.

It was transcribed

and posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.