A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

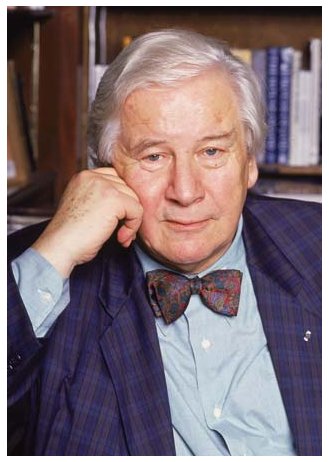

Ustinov: I think it is not to treat it as a comedy and

not to treat it, certainly, as a tragedy. For some reason, Don Giovanni is treated, now, as a tragedy,

with the terrible scene when he's drawn to Hell. I don't think that

it is tragic for a person to have slept with 300 women in one town.

It may be athletic, but it's certainly not a tragic occurrence. It's

called a dramma giocoso.

There is the little morality at the end, which people like Klemperer always

took out in order to end on a "strong," and I think that's absolutely and

utterly against the intentions of Mozart.

Ustinov: I think it is not to treat it as a comedy and

not to treat it, certainly, as a tragedy. For some reason, Don Giovanni is treated, now, as a tragedy,

with the terrible scene when he's drawn to Hell. I don't think that

it is tragic for a person to have slept with 300 women in one town.

It may be athletic, but it's certainly not a tragic occurrence. It's

called a dramma giocoso.

There is the little morality at the end, which people like Klemperer always

took out in order to end on a "strong," and I think that's absolutely and

utterly against the intentions of Mozart. Duffie: When you're directing an opera of Mozart or

others, do you take most of your ideas for direction from the text, or from

the music to which the text has been set?

Duffie: When you're directing an opera of Mozart or

others, do you take most of your ideas for direction from the text, or from

the music to which the text has been set? Duffie: Were you ever conscious of trying to mold them

in such a way that the next director – or the third

and fourth director after that – would still be able

to have some malleability on their part?

Duffie: Were you ever conscious of trying to mold them

in such a way that the next director – or the third

and fourth director after that – would still be able

to have some malleability on their part? Ustinov: I think the desire to hear opera has enormously

increased, especially by virtue of the fact we all have discs and tapes and

goodness knows what. Even obscure operas are now on record in some way

or other. I think the general desire for opera, and the spread of opera

houses in towns which before never had them, is very, very striking!

But whether it is absolutely possible... I mean the way music has gone,

it's drifted very, very far away. To my mind, there's a huge gap between

modern serious music and modern popular music. The 12-tone system and

all sorts of ideas have been tried, but now we're drifting back again.

You can see the parallel thing in architecture, when everybody was building

these huge boxes which were very fashionable at one point. Now we have

a kind of austerity, the "back-to-Bach" architecture. Bits of Romanticism

are creeping back in; Gaudí has had his effect, and you're getting

that again, but with modern serious music, I can't imagine anybody whistling

Stockhausen in the bath unless they're extremely unmusical and are doing it

by mistake! There's no reflection on Stockhausen, whom I find fascinating

as a composer, but it's something else now. All the Boulez things and

all those others, my ear isn't fine enough to distinguish between them anymore.

I can't say that is typical of this composer and that is typical of that one.

[See my interviews with Pierre Boulez.]

Ustinov: I think the desire to hear opera has enormously

increased, especially by virtue of the fact we all have discs and tapes and

goodness knows what. Even obscure operas are now on record in some way

or other. I think the general desire for opera, and the spread of opera

houses in towns which before never had them, is very, very striking!

But whether it is absolutely possible... I mean the way music has gone,

it's drifted very, very far away. To my mind, there's a huge gap between

modern serious music and modern popular music. The 12-tone system and

all sorts of ideas have been tried, but now we're drifting back again.

You can see the parallel thing in architecture, when everybody was building

these huge boxes which were very fashionable at one point. Now we have

a kind of austerity, the "back-to-Bach" architecture. Bits of Romanticism

are creeping back in; Gaudí has had his effect, and you're getting

that again, but with modern serious music, I can't imagine anybody whistling

Stockhausen in the bath unless they're extremely unmusical and are doing it

by mistake! There's no reflection on Stockhausen, whom I find fascinating

as a composer, but it's something else now. All the Boulez things and

all those others, my ear isn't fine enough to distinguish between them anymore.

I can't say that is typical of this composer and that is typical of that one.

[See my interviews with Pierre Boulez.] Ustinov: That's true, it isn't a straight setting.

You regret it less because you feel, "Oh, God, it takes place in Venice with

a Moor; that's really Italian territory so let them have a shot." But

King Lear is ancient Britain, and

Hamlet is Denmark. Carl Nielsen

might have a crack. [Laughter]

Ustinov: That's true, it isn't a straight setting.

You regret it less because you feel, "Oh, God, it takes place in Venice with

a Moor; that's really Italian territory so let them have a shot." But

King Lear is ancient Britain, and

Hamlet is Denmark. Carl Nielsen

might have a crack. [Laughter]  Duffie: Some of these things have been overworked.

I've been lobbying for a long time to take many of the warhorses completely

out of the repertoire for ten years, and then put them back gradually so that

we come to them fresh!

Duffie: Some of these things have been overworked.

I've been lobbying for a long time to take many of the warhorses completely

out of the repertoire for ten years, and then put them back gradually so that

we come to them fresh!|

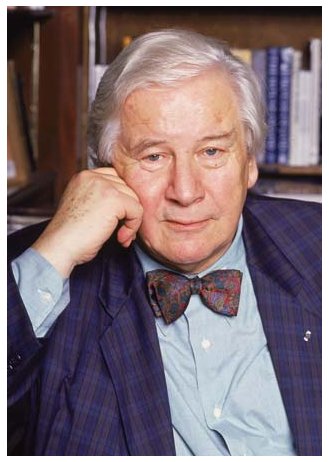

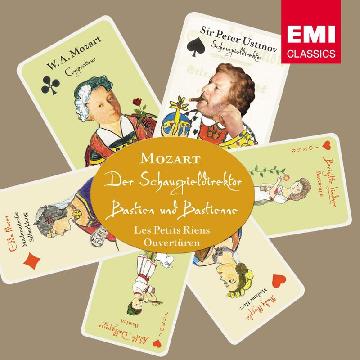

Peter Ustinov

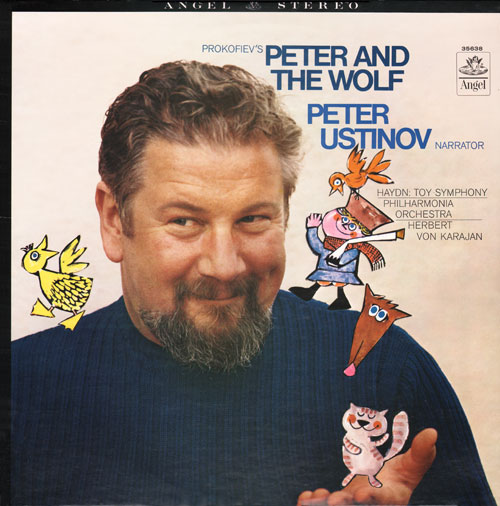

Oscar winner Sir Peter Ustinov dies at 82 Sir Peter Ustinov, a wit and mimic who won two Oscars for an acting career that ranged from the evil emperor Nero in "Quo Vadis'' to the quirky Agatha Christie detective Hercule Poirot, has died. He was 82. Ustinov, whose talents included writing plays, movies and novels as well as directing operas, also devoted himself to the world's children for more than 30 years as a goodwill ambassador for UNICEF. He died of heart failure Sunday in a clinic near his home at Bursins overlooking Lake Geneva, said Leon Davico, a friend and former UNICEF spokesman. Born in London, the only son of a Russian artist mother and a journalist father, Ustinov claimed also to have Swiss, Ethiopian, Italian and French blood -- everything except English. Ustinov delighted in national differences and frequently referred to them in his works and public appearances. He was -- as he noted proudly in his autobiography "Dear Me'' -- conceived in Russia, baptized in Germany and reared under a succession of Cameroonian, Irish and German nurses. His imposing figure, variously described as resembling a teddy bear or a giant panda, began at 12 pounds at birth and stayed with him throughout his career. Ustinov made some 90 movies and also wrote books and plays. He directed films, plays and operas. His narration of Sergey Prokofiev's "Peter and the Wolf'' won him a Grammy. Among his film roles were a nomad in the outback who befriends a family in "The Sundowners,'' a one-eyed slave in "The Egyptian,'' Inspector Poirot in "Death on the Nile,'' and Abdi Aga, an illiterate tyrant in "Memed My Hawk.'' Ustinov won best supporting actor Oscars for the role of Batiatus, owner of the gladiator school in "Spartacus'' (1960), and as Arthur Simpson, an English small-time black marketeer in Turkey who gets caught up in a jewel heist in "Topkapi'' (1964). His Nero -- the Roman emperor who presided over the throwing of Christians to the lions -- won him a Golden Globe for best supporting actor in the 1951 movie "Quo Vadis.'' He also won three Emmys, portraying Samuel Johnson in "Dr. Johnson,'' Socrates in "Barefoot in Athens'' and an aged Jewish delicatessen owner in "A Storm in Summer.'' He directed, wrote the screenplay and starred in the 1962 movie "Billy Budd.'' He was performing by age 3, mimicking politicians of the day when his parents invited Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie for dinner. His first attempts at acting were in the disguise of a pig in a dramatized nursery rhyme, as Friar Tuck of Robin Hood fame and as one of three nymphs tempting Ulysses. "Ulysses wisely passed us by,'' he recalled. He was educated at the Westminster School, but hated it and left at age 16. At age 19, he appeared in his first revue and had his first stage play presented in London. Ustinov turned producer at 21, presenting "Squaring the Circle'' before entering the British army in 1942. If his plays had a continuing theme, it was a celebration of the little man bucking the system. One of his most successful was "The Love of Four Colonels'' which ran for two years in London's West End. Davico asked Ustinov to join the U.N. children's agency as a goodwill ambassador after seeing the play. Davico said Ustinov recently attended a UNICEF event despite needing a wheelchair -- sciatica gave him trouble walking, and diabetes left him with 30 percent vision and foot problems. Ustinov also set up a foundation dedicated to understanding between people across the globe and between generations. "I think knowing people is the best way of getting rid of prejudices. When I was young, I was brought up in an atmosphere which was just loaded with prejudices,'' he said in 2001. Ustinov treated getting older the way he treated everything else in life - as another experience to be added to his repertoire of anecdotes, quips and material for books. When he turned 60, Ustinov was asked if he was tempted to take things a little easier. "I only feel 59,'' he said. "But what really surprises me,'' he added, "is that I don't say many different things now than I did when I was 20. The only difference is that having white hair means that people tend to listen now while they never did before.'' It was an attitude that stayed with him as he turned 80. "Why should one slow down? I don't quite understand it,'' he said in an interview with The Associated Press in 2001. Ustinov's son Igor said his father viewed his own mortality with humor. Responding to an interviewer who asked what Ustinov would like to see on his tombstone, he reportedly said: "Keep off the grass.'' When he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1990, his main worry was how to reply to the invitation from the palace. "The invitation said, 'Delete whichever is inapplicable: I can kneel -- I cannot kneel.' But there was nothing for those who can kneel but not get up,'' Ustinov recalled. He remained active until close to his death, playing himself in the 2003 TV movie "Winter Solstice.'' In other late roles, he was the voice of Babar the Elephant, portrayed a doctor in the film "Lorenzo's Oil,'' and in 1999 appeared as the Walrus in a TV movie version of "Alice in Wonderland.'' Ustinov was married three times, and is survived by four children and his third wife, Helene du Lau d'Allemans. |

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on

May 22, 1992. Sections were used (along with recordings)

on WNIB the next day, and again in 1996. The full interview

was transcribed and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.