|

Aribert Reimann was born on 4 March 1936 in Berlin. He grew up in a musical family; his father was an organist and director of the Berlin State and Cathedral Choir, his mother was a renowned oratorio singer and singing teacher. Reimann composed his first lieder with piano at the age of ten. After having passed his Abitur [higher education entrance examination] in 1955, he worked as repetiteur in the Studio of the State Opera House in Berlin and simultaneously studied composition with Boris Blacher and Ernst Pepping and piano with Otto Rausch at the Academy of Music in Berlin. He gave his first concerts as pianist and lied accompanist in 1957. A year later, he attended the University of Vienna to study musicology.

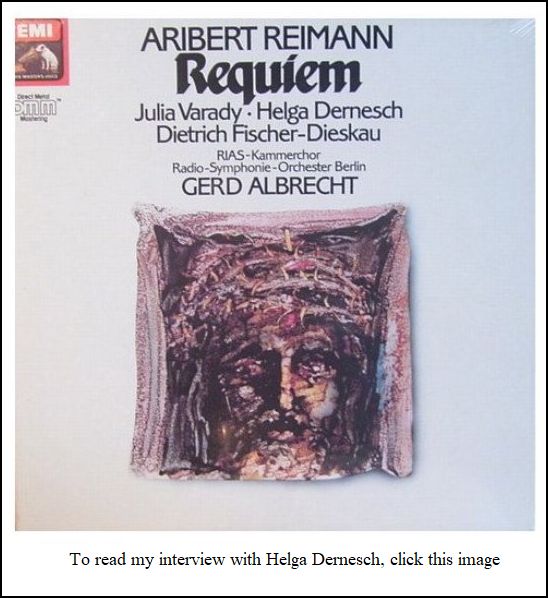

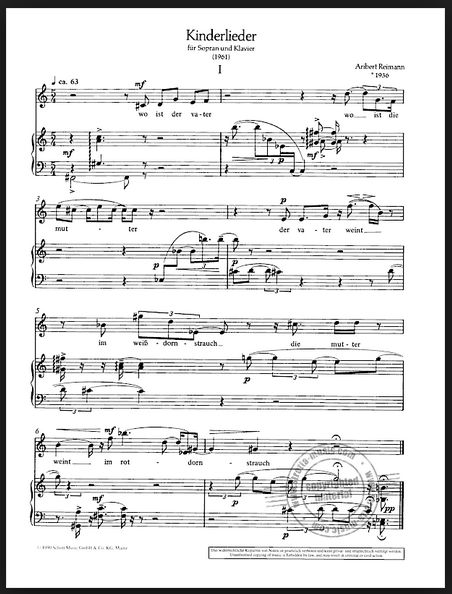

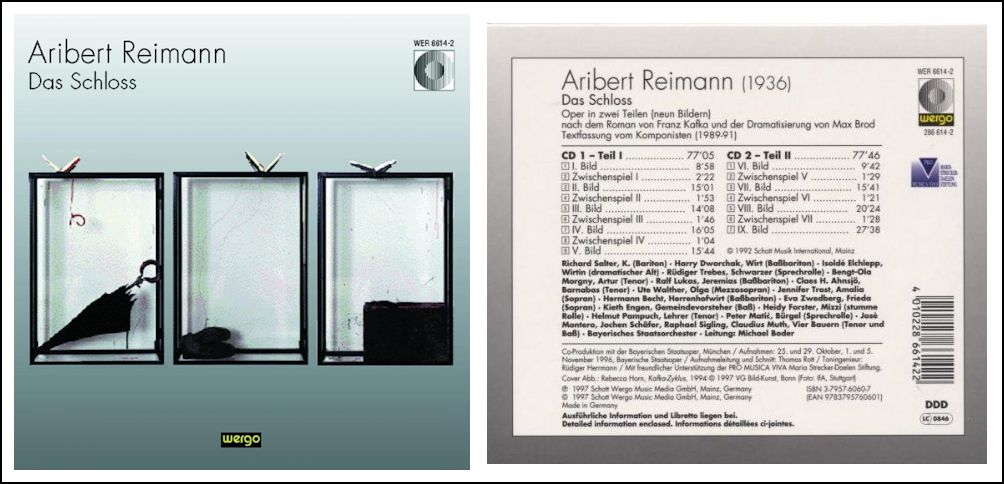

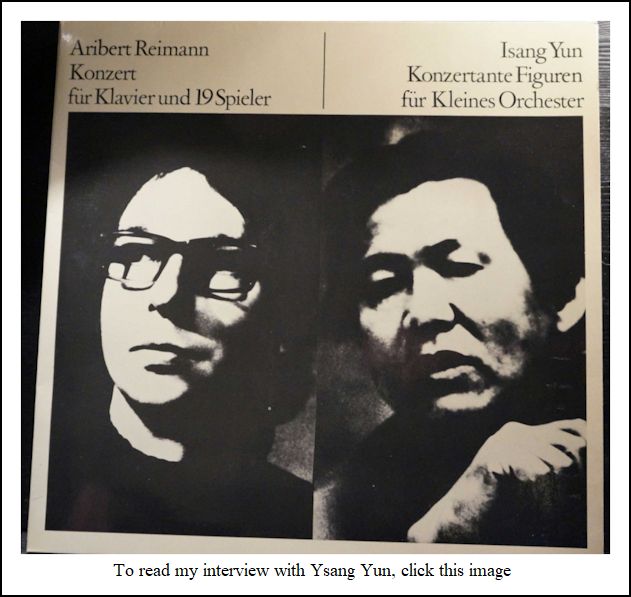

The affinity for the human voice provides a strong impulse for Aribert Reimann’s compositional activity. Alongside lied settings of texts by authors such as Paul Celan, James Joyce, Joseph von Eichendorff and Louïze Labé, the composer has also produced numerous chamber music works, solo concertos and orchestral works such as Miniatures for string quartet (2004/05), the two Piano Concertos (1961 und 1972), Seven Fragments for Orchestra (in memoriam Robert Schumann, 1988) and the orchestral work Zeit-Inseln (2004). Reimann’s operatic output began in 1965 with the first performance

of Ein Traumspiel based on a text by August Strindberg

in Kiel. This was followed by Melusine, based

on the play by Yvan Goll, premiered at the Schwetzingen Festival in 1971.

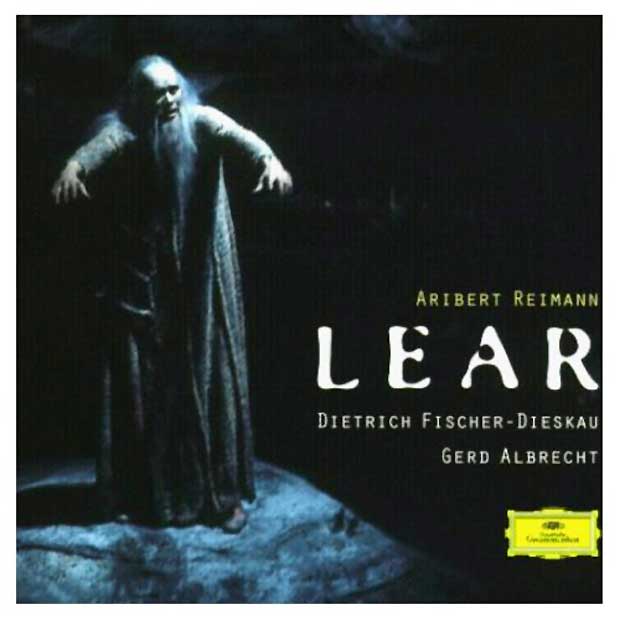

With his opera Lear (1978, Bayerische Staatsoper),

Aribert Reimann was able to win over not only specialists and critics but

also a wider public for his characteristic personal style. The work has

been performed internationally in more than thirty productions. With its

basis on the play by William Shakespeare, the composer created music with

an almost physical directness which is at all times aware of its existence

on the borderline to being struck dumb. In 1984, Die Gespenstersonate,

also on a text by August Strindberg, was premiered in Berlin and, in 1986,

Troades based on the play by Euripides

in the version by Franz Werfel.

Aribert Reimann has received numerous honours and awards, including the Grand Cross for Distinguished Service of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1985, the 'Prix de composition musicale de la Fondation Prince Pierre de Monaco' in 1986, the Bach Prize of the Free Hanseatic city of Hamburg in 1987, the Order of Merit of the State of Berlin in 1988, in 1991 the Frankfurt Music Prize, the Grand Cross with Star for Distinguished Service of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1995, the Goldene Nadel from the Dramatiker Union in 2002, the Berlin Art Prize for Music and the medal of the Free Academy of Arts in Hamburg in 2002, the Arnold Schönberg Prize in 2006 and the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize in 2011. In 1999, Reimann was appointed as Commandeur de 'L'Ordre du Mérite Culturel de la Principauté de Monaco’. He is also a member of the Order Pour le Mérite for science and the arts and honorary member of the German Music Council. -- From the Schott Website [Text only - photos

added for this presentation]

|

Here is our conversation . . . . . . . . .

Here is our conversation . . . . . . . . .  BD: Where is the balance between head

and the heart?

BD: Where is the balance between head

and the heart?

BD: When you’re writing, and you’re

looking down at the page and getting ideas, are you creating these ideas

or are you discovering these ideas?

BD: When you’re writing, and you’re

looking down at the page and getting ideas, are you creating these ideas

or are you discovering these ideas?  BD: Let me ask a very easy question.

What’s the purpose of music?

BD: Let me ask a very easy question.

What’s the purpose of music?  AR: Yes, and this is very good.

I also learned, of course, from playing. I played the whole set

of Webern songs, and Berg and Schoenberg. You can learn a lot of

things, but the influences are in the conservatory way. I played

much of their music, but I have nothing to do with it for my composing.

AR: Yes, and this is very good.

I also learned, of course, from playing. I played the whole set

of Webern songs, and Berg and Schoenberg. You can learn a lot of

things, but the influences are in the conservatory way. I played

much of their music, but I have nothing to do with it for my composing.

AR: It’s difficult to say. If I get commissions, they

come very, very early, and I plan for the next five years. So when

commissions come now, I have to say no, it’s not possible. Sometimes

a commission comes to write a piece for a strange cast, or a chamber music

cast, or something when I have the feeling it’s not for me. Then it’s

better if it goes to another composer.

AR: It’s difficult to say. If I get commissions, they

come very, very early, and I plan for the next five years. So when

commissions come now, I have to say no, it’s not possible. Sometimes

a commission comes to write a piece for a strange cast, or a chamber music

cast, or something when I have the feeling it’s not for me. Then it’s

better if it goes to another composer.  BD: Well, start with singers who want to improve their

technique and be better at performing music of today.

BD: Well, start with singers who want to improve their

technique and be better at performing music of today.

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 16, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2001. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at itive. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.