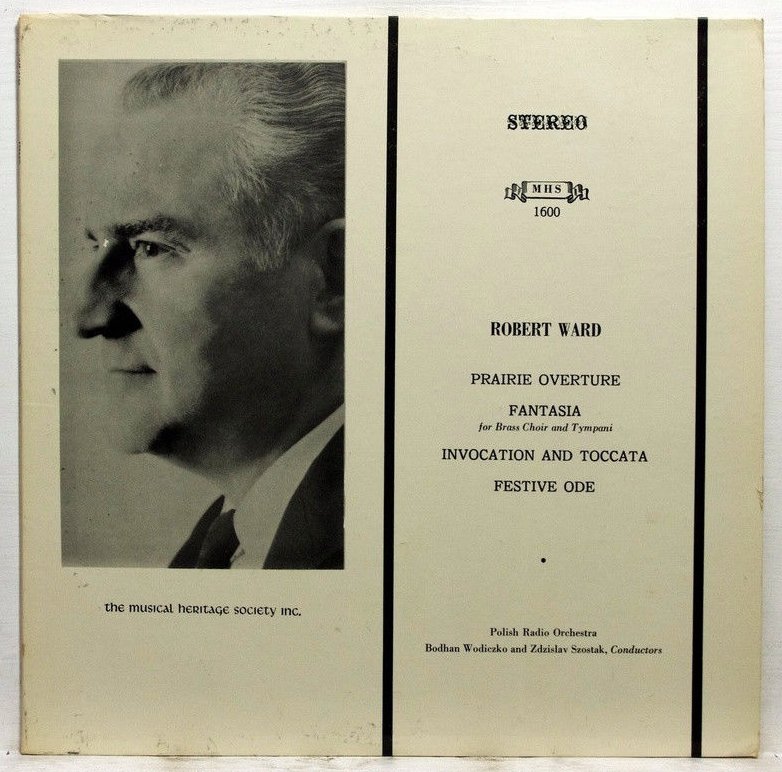

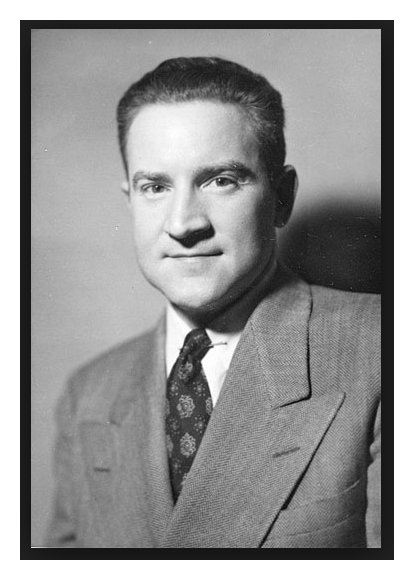

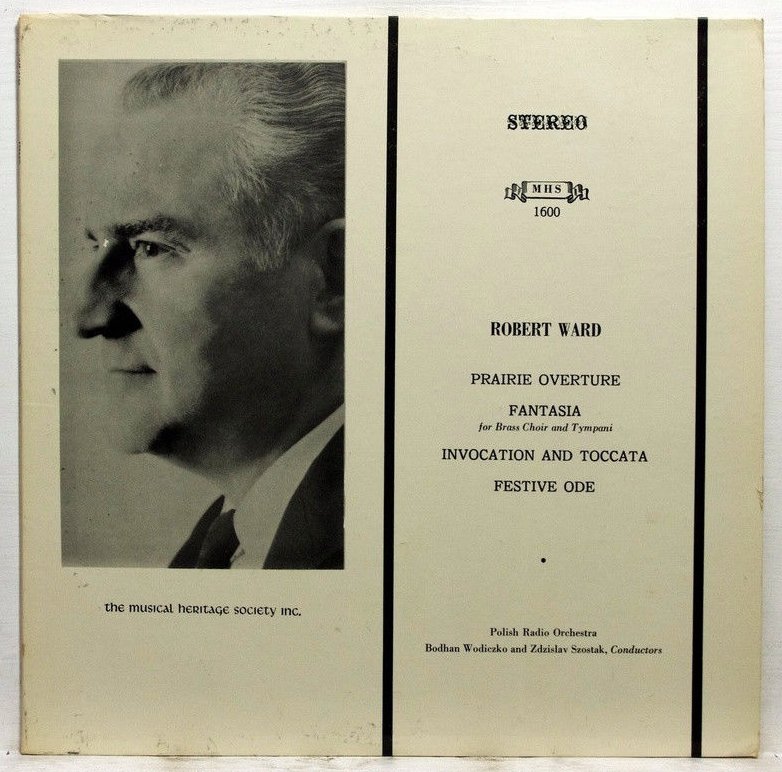

Composer Robert Ward

The First of Two Conversations

with Bruce Duffie

This first conversation with Robert Ward took place in May of 1985,

when he was in Chicago for a production of The Crucible by the Chicago Opera

Theater, in which a new orchestration was being presented for the first

time. [The second conversation, which took place in 2000 and was

published in The Opera Journal,

can be seen here.]

This first meeting took place at the home of Alan Stone, the Founder

and Artistic Director of the COT, and he provides a few details about

this version during the interview.

Bruce Duffie:

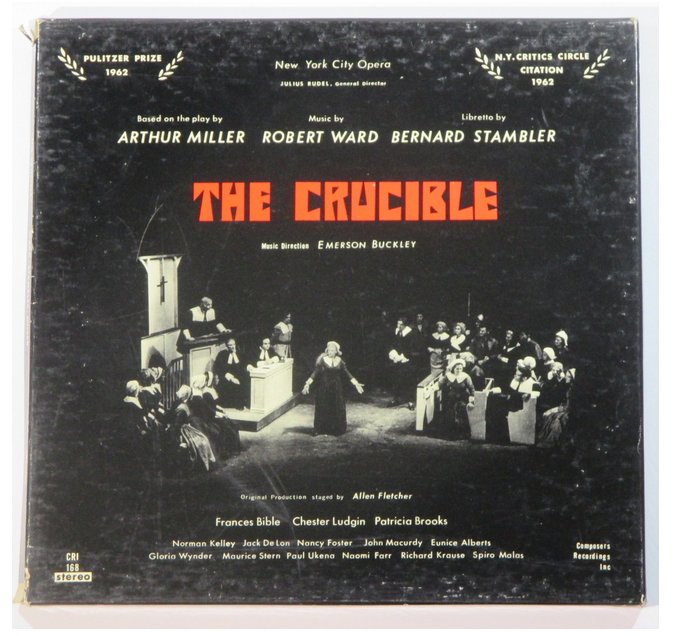

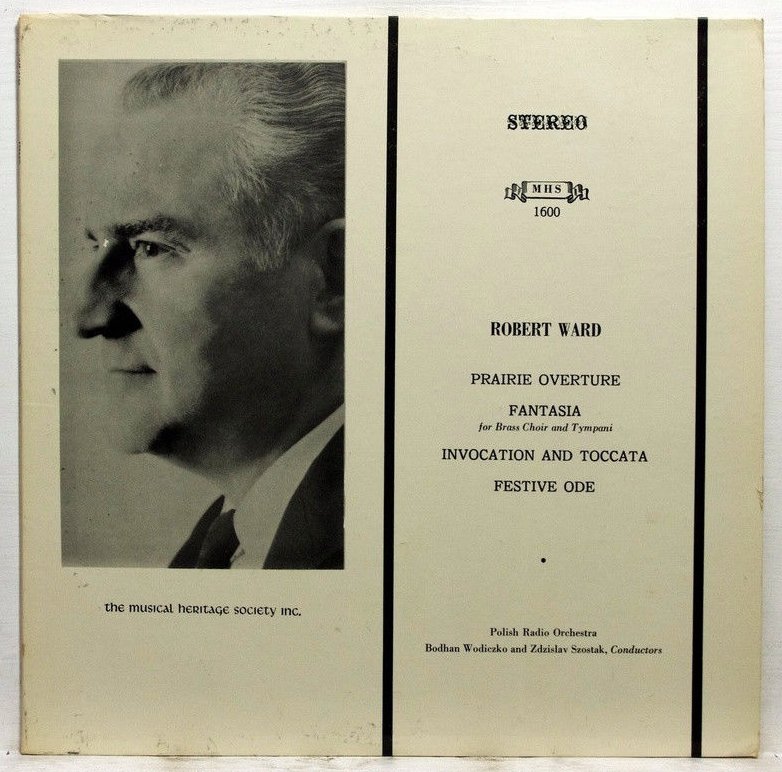

The

Crucible won the Pulitzer Prize and now is being done in a new

orchestration which was written especially for the Chicago Opera

Theater, so my first question is the obvious one — why

tamper with

success?

Robert Ward: Over

the years since The Crucible

was first performed, a number of people have asked me if there was a

reduced version of the orchestra, because they were operating in

smaller theaters or they had a very small pit. That idea actually

has always appealed to me for the simple reason that because of the

rather intense dramatic nature of the libretto, The Crucible in

fact fares better, I feel, in a small theatre where those values can

come through better than it does in some of the vast houses in which so

much opera takes place in today. So that when Alan Stone of the

Chicago Opera Theater approached me

on this, it came at a time when I was not under a terrible deadline

to get some piece finished, and I felt the moment

was kind of right. One of the reasons that it was right was

that I had heard such very good reports of the productions which were

done here with his group that I decided this was the right

moment for it. So I undertook it for that reason.

Robert Ward: Over

the years since The Crucible

was first performed, a number of people have asked me if there was a

reduced version of the orchestra, because they were operating in

smaller theaters or they had a very small pit. That idea actually

has always appealed to me for the simple reason that because of the

rather intense dramatic nature of the libretto, The Crucible in

fact fares better, I feel, in a small theatre where those values can

come through better than it does in some of the vast houses in which so

much opera takes place in today. So that when Alan Stone of the

Chicago Opera Theater approached me

on this, it came at a time when I was not under a terrible deadline

to get some piece finished, and I felt the moment

was kind of right. One of the reasons that it was right was

that I had heard such very good reports of the productions which were

done here with his group that I decided this was the right

moment for it. So I undertook it for that reason.

BD: Are you happy

with the orchestration as it is now?

RW: We have just

come this afternoon from the

first reading of the reduced orchestration, and at the intermission I

said to Alan, “If I had just walked into this rehearsal

without realizing there was such a thing at the reduced orchestration,

I would hardly have known.” Except for a few places where there

are some

colors, which because of some substitutions that had to be done, I

would not have been aware. But otherwise, I think that someone

who knows it

a little less well than I do would probably be very little aware of the

difference. It’s a little brighter and it’s a little

clearer. I have

not used wind instruments in some places where I did before, and if

anything that lightens it up a little bit, but I think in no way in a

negative sense.

BD: Have you

tampered with anything but the

orchestration — any of the melodic lines or

harmonies?

RW: No, otherwise

it’s exactly the same.

BD:

This production is in three acts instead of the original four?

Alan Stone: We

combine Act One and Act Two and make

one act with two scenes. That way we do it with two intervals.

BD: Why not

telescope both ends so that there is just one

interval in the middle?

AS: There’s one

scene that is really the climax

of the piece, which is the courtroom scene at the end of the original

Act Three. We need to give the

audience some respite. Anything following that, if it followed

immediately, would have to be anticlimactic. The prison scene is

very

powerful, too, but that scene really needs an intermission, so that’s

why

we decided on two intermissions and three acts.

RW: In fact both

the First and Second Acts are really expository

acts. The first one is expository in the social climate of

Salem.

That’s what you know about when that act is over, but you really

don’t know about the most important individual relationship, which is

that between John and Elizabeth Proctor, and what’s going to happen

there until the end of the Second Act. Early on, our experience

— Bernard Stambler’s and mine — was

that it

really was better to combine the first two acts. They don’t

make an unusually long First Act. It should run about fifty

minutes, so we

recommend that it be done that way.

BD: How

did winning the Pulitzer Prize affect the progress and

the performances of this opera?

RW: It’s a little

hard to say. There is no question

that the Pulitzer Prize is the greatest piece of promotion that any

piece can have. On the other hand, the idea that if you get the

Pulitzer Prize for a work automatically is going to result

in many, many performances simply isn’t true. You can

name Pulitzer Prize winning pieces which have immediately had a

lot of performances, but I

happen to have been sitting on the jury for one we thought was a great

piece, but it was twenty years after it

won the Pulitzer Prize before it ever got another performance.

So it’s not a guarantee that every orchestra in the

country — or every opera company — is

going to pick the piece up by any

means. But there is no doubt that it helps, and it helps one’s

whole

career because being a newspaper prize, the minute you arrive

in a town the newspapers say this guy must be OK because the newspapers

said

he was all right.

BD: You’ve written

quite a number of other operas. Do you

like being known as an opera composer, or would you prefer it was just

as a composer?

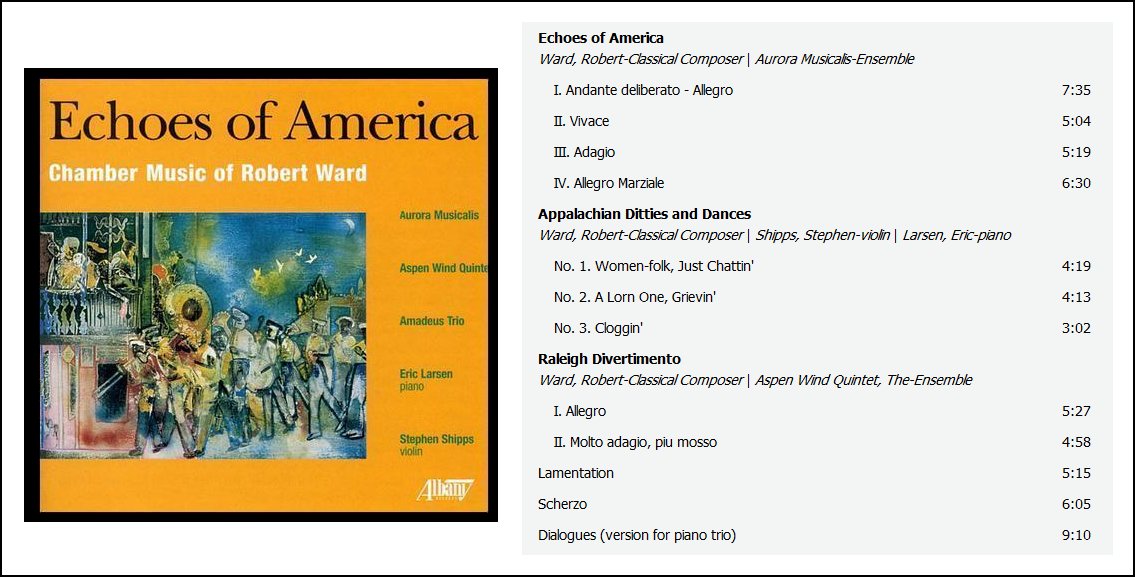

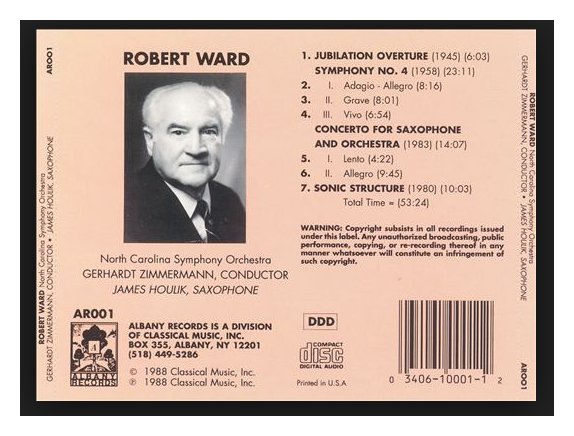

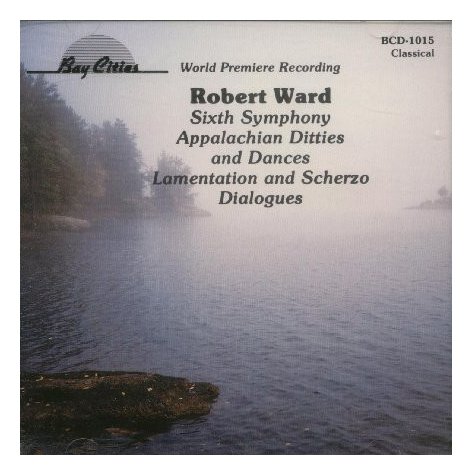

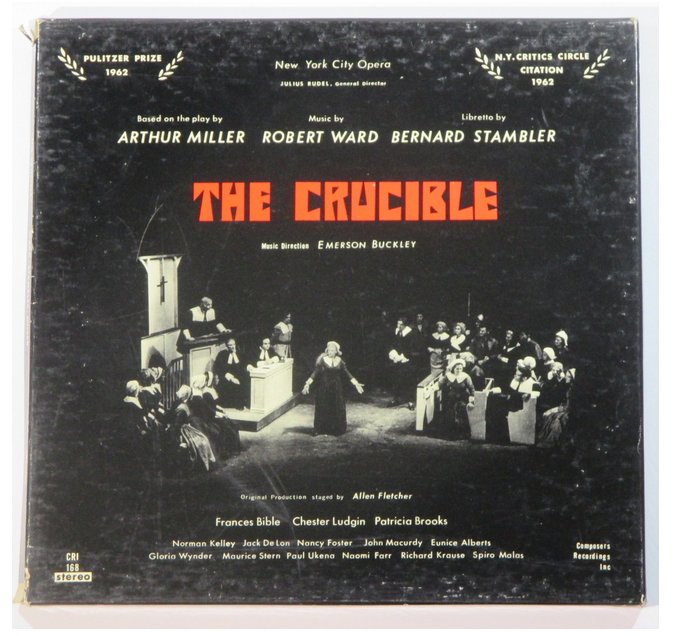

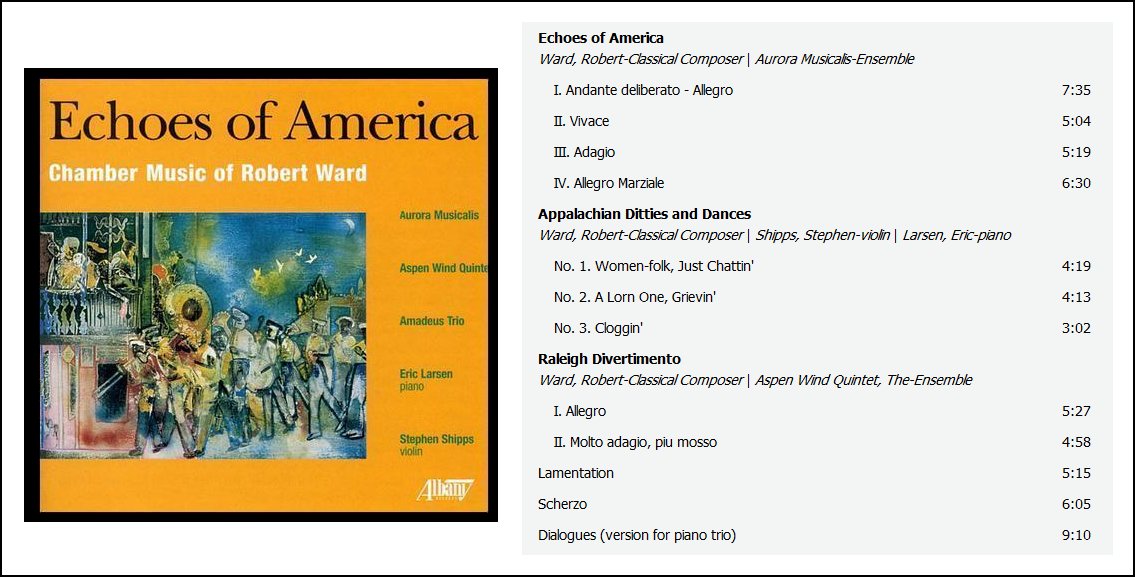

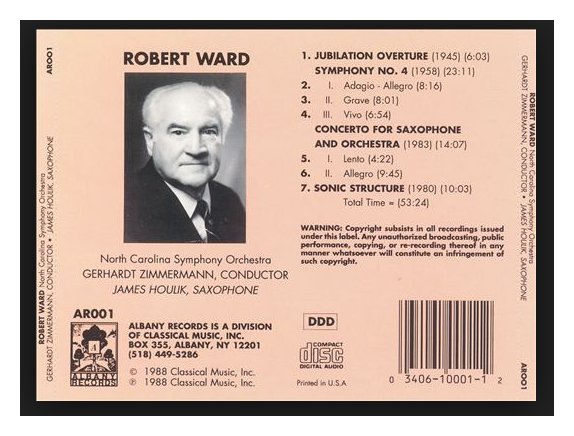

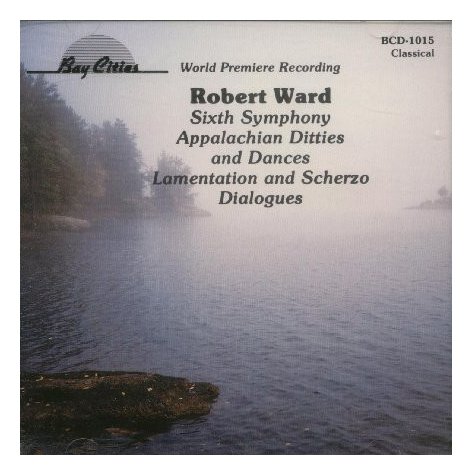

RW: My output has

been pretty much balanced between the

various media. I have written six operas, five

symphonies, a number of large choral works and some

chamber music, so I have operated through a

generality of the media rather than being almost completely an opera

composer as, say, Wagner and Verdi and Puccini were.

BD: Why does it

seem so difficult for American operas to get

hearings, especially in the big houses today?

RW: The big houses

are so tied into the star system, and the

way that works is if you’re going to engage

one of the singers that are really the top

stars, they are scheduled for three to four years ahead. So if

you were to approach them with the idea of doing a contemporary

opera, it’s very difficult for them to fit this into their

schedule. It isn’t simply because they don’t want to do

it; many of them would be very interested, but those

companies are also very conservative. So I think it is the

combination of those two things.

BD: Are the

companies making the public conservative or is the

public making the company conservative?

RW: I am rather

convinced that if the Metropolitan suddenly decided to do one of those

operas by American composers which

has had great success — and there are about ten

of them that I could

mention which have been played widely and received very favorably

— if they

simply took one of those and did it every year and did it on

television in their broadcasts, this would have a tremendous effect for

the whole field of American opera. They could also command the

Leontyne Prices and other star singers to do it.

BD: Would The Crucible work well with

Leontyne Price and Sherrill

Milnes in the cast?

RW: I don’t know

what Leontyne would do in it since

she’s not doing any opera any more... Actually Leontyne was a

student of

mine at The Julliard School, so I have known her from way back then,

but when I occasionally see Sherrill Milnes, the

greeting that he always sings me is a line from The Crucible because he knows

it. I think it would not take a great deal to

interest him in doing the John Proctor role which he’s absolutely

ideally suited for. He’d be a marvelous.

BD: I

look forward to this new production very much.

BD: I

look forward to this new production very much.

RW: I hope you

enjoy it. I was wonderfully impressed

with the rehearsal today, especially with the orchestra because it’s a

first-rate

young group.

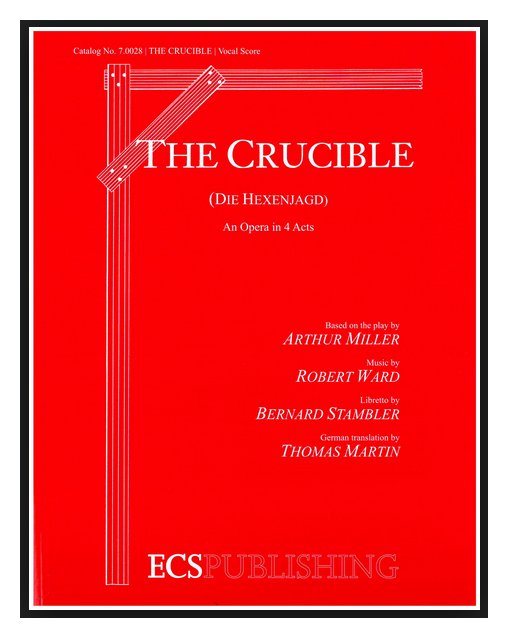

BD: If a German

company or French company or Portuguese

company came to you and wanted to do The

Crucible in translation, would

that be a good idea from your point of view?

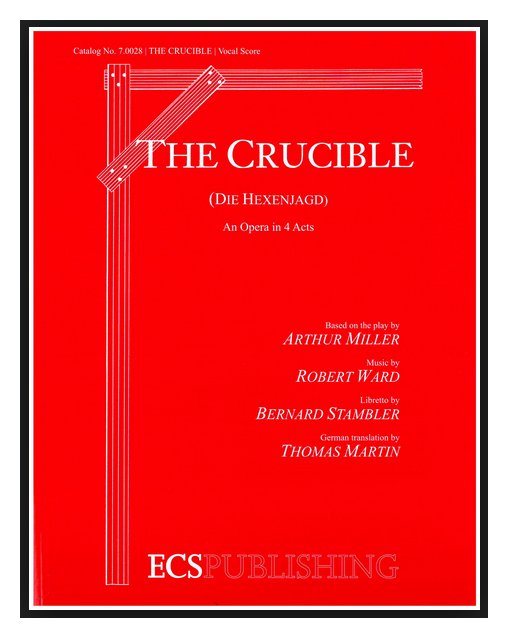

RW: Yes. As

a matter of fact, I’ve conducted it in Germany in

German [see cover of score shown at

left]. Two years ago it was done in Japan in Japanese, and

I’m going to conduct it this summer in Korea in Korean. I am

very much in favor of this. We’re at a curious moment in

all of this because some of the companies are now going back and doing

them in the foreign [original]

language and depending on the projection of titles.

BD: Is that good

idea from your standpoint?

RW: My main

feeling is that the

audience should understand the words of what they’re seeing and

hearing. How this is achieved doesn’t matter that much to

me. I think to do everything in English has certain

merits, but I think we all know that just because it’s sung in English

doesn’t mean you hear and understand every word. The important

thing is that the audience

understands what they’re listening to.

BD: Would you

object if the performance was being done in English with Supertitles?

RW: I’ve thought

about this and I don’t know. I’d have

to experience it to know whether this would be desirable or not.

I have no idea.

BD: Have you seen

productions with Supertitles?

RW: No, not of

this opera.

BD: What about

other operas?

RW: Oh, yes I’ve

seen many.

BD: Do they do the

job of bridging the gap between the libretto and the audience?

RW: Yes they

certainly do if they are good. Some

of them are very ridiculous; they’re laughable because they are so

condensed. If you have a long love scene and all you get on

the Supertitles is, “You’re a great gal,” or “Yeah, I go for

you,” that doesn’t really help

the opera. But if it was well done I think it could be very

effective.

BD: Of course when

the text is repeated a lot and the same phrase of

text comes back, such as “T’amo,

t’amo…” [Both laugh]

RW: That’s

right. On the other hand, it could well be that

a contemporary opera would be very difficult to do that way because you

don’t have those textual repetitions in contemporary opera.

BD: Is there too

much text in contemporary opera?

RW: There may be

too much for the first time you listen,

but maybe it will be fine by the fifth time. The nature of

opera is such that its values are not discovered once around. I’m

sure that you could think of many, many people who have heard

Bohème or Magic Flute 50 fifty times.

After the first couple times, they know the story and

they know what the text is all about, but that’s not what you go to

opera for. I think we have to develop a sense in our

audiences of recognition that opera is not just to go hear a

text. There’d be no point I writing an opera if that was all it

was about.

BD: Which is more

important, the music or the text?

RW: Maybe I can

best illuminate this one by one of the

earliest conversations I had with Arthur Miller when I became

interested in The Crucible.

It turned out that when he

was working on the play and first came to consider it, he thought

that it might make a better opera than a play. But

in any case, during the course of our first discussion, there was a

bridge I thought had better be crossed first rather than last because

it could mean the end of the whole thing. We had gotten along

very well, so finally I said, “Look, there’s one

thing that I need to say right now. I think your play is a

masterpiece, and you’ve even kind of orchestrated it with this

marvelous

use of this Elizabethan language,” which he had gotten from the

trial records and so forth. I continued, “It doesn’t need

a little bit of incidental music to go along and I have no intention of

writing some incidental music for a great play. If this

is going to be an opera, the music is going to have to be the first

value.” I was prepared for him to clear his

throat and say,

“Well, it was nice that we got together,” but quite the contrary!

He

said, “I couldn’t agree with you more.” He was doing a film of The Misfits at that time, and he

launched into a monologue which was one of the most perceptive visions

of the various values in opera, ballet, the movies, and where

the greatest intensity of value could be. So when I told him that

we

would have to reduce in sheer number the words in his

play to about one third of what was there, that didn’t shock him at

all. He was marvelous from beginning to end about that, and this

was very different. I had known of composers’

experience with some writers who, the minute you wanted to touch a word

they had written, “Sorry, you can’t do that,” and

that was the end of that project because you just can’t work like that

in the theater. So Miller was perfectly marvelous.

BD: Have you had

to work with people who would not let you change

a word?

RW: Some of

the writers were dead — such as Ibsen and Andreev

— so that was not a problem. The operas I’ve done

which had original libretti I was involved from the beginning of the

planning right

through the whole writing. I have had a very good time with those

living authors.

BD: If a young

composer asks you for advice about writing an opera, should they look

first for a story

or a text or a librettist?

RW: Absolutely it

has to come from the libretto. It has to

be something that they can really get excited about, that they can

empathize with, and that is suitable for them and the kind of music

that

they write. Young composers very often don’t know

that; they have very funny kinds of ideas. Suddenly they

have come up with a rather cynical, hard-boiled kind of character,

yet what they want to do is some vastly romantic work like Cyrano de Bergerac, and it’s

totally

unsuited for them. They don’t realize this right off, so the

first thing I deal with when young composers work with me is to

get a libretto which is right. I make them actually go through

the exercise of writing a libretto, so that they really appreciate

what a good librettist is.

BD: So they see

their own failings in it?

RW: That’s right.

*

* *

* *

BD: Do the older

operas still speak to us on the stage today — even

going back as far as Handel and

Monteverdi?

RW: One can’t

generalize about all of them because

some do much better than others. I have no trouble with anything

from Mozart on, even some Monteverdi doesn’t bother me that way.

But with the libretti of the Handelian operas, I find great problems

because the music is so incredible and so marvelous and yet it was

tied to certain traditions — all the da capos, the long introductions

and

the repetitions — that you don’t have any kind

of dramatic impact. As a

matter of fact if I could find the time, I’ve long felt that I would

love to take one of the great Handelian operas that have some of the

greatest music ever written for opera, and work with a very sensitive

contemporary writer to reconceive the

whole book. We could tighten these up to be the powerful two- to

two-and-a-quarter

hour shows which I think is in them. It would be a glory;

you’d have that magnificent music, but it would be in a thing with a

kind of dramatic impact. I wouldn’t hesitate to do this for a

minute, as I don’t think Handel would have hesitated to it in his

day. He adapted himself very well to the values of his time.

BD: As the world

keeps getting faster and faster and everything

becomes micropressed and microchipped, supposed two hundred years from

now some composer of operas that are in vogue that run 42 minutes

each says, “We should take the operas of Robert Ward and

condense them into the 42 minute length.” What do you say to

that?

BD: As the world

keeps getting faster and faster and everything

becomes micropressed and microchipped, supposed two hundred years from

now some composer of operas that are in vogue that run 42 minutes

each says, “We should take the operas of Robert Ward and

condense them into the 42 minute length.” What do you say to

that?

RW: If they kept

the basic values which are in my shows,

which are the fundamental story line — the

fundamental characters and

the dramatic situations that are embodied in them — I

wouldn’t

object. I will say that I think it might be harder in The Crucible than in some other

operas because The Crucible

is conceived in a way as a kind of four-movement

symphony. You can’t exactly go into a Beethoven symphony and

cut sixteen bars here and another thirty bars there because it’s

conceived

from beginning to end. That’s the way the acts of The Crucible are set up.

There aren’t introductions to arias or tailings on

ensembles. They don’t exist in it.

BD: So your work

has nothing that’s

insignificant?

RW: Well, at least

as I’ve conceived it structurally. I

believe that to be true. Now that doesn’t mean that it is all

sheer gold, and it’s other peoples’ points of views that are ultimately

more important than mine. But at least my conception of music

drama is that it has a kind of tightness dramatically where you can’t

take a note out of it. As you know, the opera The Crucible is

shorter than the play. It’s more succinct, and the things that we

have cut, I think, have not in any way destroyed any dramatic

line. In fact, when working with Miller that was the one thing he

felt very strongly about, that it should in no way ever be

hurt in the piece.

BD: And you feel

that you succeeded?

RW: Yes, I

think we did.

BD: When you are

writing an opera, are you writing for yourself

or for a public, and if a public, which public?

RW: Ultimately all

you can write is for yourself because you can’t take it out there and

ask if they like this,

and then take it to thirty more people, and if twenty don’t like it

then you decide to take it back and rework it. You can’t do

that. But if I am asked to write a string quartet for an audience

that

is going to be a highly specialized audience in that field, I will

write

it with kind of that ambience in mind. When I write a work

for an opera house, that would be rather a different work — even

form the choice of the subject itself — than a

work I would do if

someone came along and said that he wanted to produce a work on

Broadway. I would probably look for a rather different kind of

story, one with those realities in mind. I really am not one that

thinks that in all of this wedding of opera and music-theatre that we

have, that it is going to go so far that there aren’t still going to be

some differences — the difference between a

Johann Strauss and a

Richard Strauss, if you like. It isn’t that one has any less

value as art than the other, but they’re different. They were

conceived

for a different kind of ambience, a different kind of audience.

BD: So the people

that are trying to blur the lines

are moving in the wrong direction?

RW: No, I don’t

think so, but I think that you can get caught up

in a kind of vague general philosophizing about this which forgets the

practical realities. Let me express this in terms of a specific

show. When you do South Pacific,

for the role of Emile de Becque you can use a great opera singer.

If he’s very appealing, he’ll do it very well.

RW: That was the

Pinza role?

RW: Yes, that was

the Pinza role. On the other hand, an opera singer is not going

to

do Bloody Mary very well. You’ve got to have

someone that can belt that thing out in Broadway style. These are

two entirely different ways of approaching vocal projection, and

so you have to deal with these things very separately. Those

are the nuts and bolts that you can’t deny if you’re going to do

this. I was at the rehearsals of Sweeney Todd

at the New York City Opera, and it was very interesting because

suddenly you had everything turned around there. In the Broadway

production, you had Broadway singers who had this heavy middle register

that they can belt things out, and they’re very shaky up on the

top. The composers have to write the top notes very carefully for

them. They

were miked up over a very small orchestra, but a rather

brash, loud orchestra. Suddenly, when New York City Opera did it,

they

had opera singers who had all the top notes, but they couldn’t belt out

those middle notes. They couldn’t sing anything else for weeks if

they

did. They also decided that they would use their full orchestra,

and it sounded like quagmire of mud down in the pit there. It

lost all of the brilliance and the sharpness of a Broadway

orchestra. You couldn’t hear the singers then over this, and so

then they ultimately miked it up somehow in order to

get the singers through. And it was in this huge hall where you

lost the visual context. So suddenly everything wasn’t quite

right about this. It isn’t that it’s not a great show

— it is — but you have to put things

in the right place.

RW: Yes, that was

the Pinza role. On the other hand, an opera singer is not going

to

do Bloody Mary very well. You’ve got to have

someone that can belt that thing out in Broadway style. These are

two entirely different ways of approaching vocal projection, and

so you have to deal with these things very separately. Those

are the nuts and bolts that you can’t deny if you’re going to do

this. I was at the rehearsals of Sweeney Todd

at the New York City Opera, and it was very interesting because

suddenly you had everything turned around there. In the Broadway

production, you had Broadway singers who had this heavy middle register

that they can belt things out, and they’re very shaky up on the

top. The composers have to write the top notes very carefully for

them. They

were miked up over a very small orchestra, but a rather

brash, loud orchestra. Suddenly, when New York City Opera did it,

they

had opera singers who had all the top notes, but they couldn’t belt out

those middle notes. They couldn’t sing anything else for weeks if

they

did. They also decided that they would use their full orchestra,

and it sounded like quagmire of mud down in the pit there. It

lost all of the brilliance and the sharpness of a Broadway

orchestra. You couldn’t hear the singers then over this, and so

then they ultimately miked it up somehow in order to

get the singers through. And it was in this huge hall where you

lost the visual context. So suddenly everything wasn’t quite

right about this. It isn’t that it’s not a great show

— it is — but you have to put things

in the right place.

BD: What is the

right place for the operas of Robert Ward?

RW: Except for one

of the

last operas, Abelard and Heloise,

which really is kind of a grand

opera and can be done in any size opera house very effectively, I would

much prefer the five

other operas to be done in smaller houses because they simply are

tight enough dramatically that they need much closer contact with the

audience with what’s going on onstage.

BD: Would they

work well on television?

RW: Very well,

yes, but to be the most

effective, I would want to do some reworking of them for television,

definitely.

BD: So it wouldn’t

be just a televised performance.

RW: No, no.

I really feel that there are all kinds of

things which I would want to do before they would be maximally

effective on television.

BD: Then would you

object if The Crucible was on

the series Live from the Chicago

Opera Theater?

RW: No, I wouldn’t

object, but if we did it and if

we had the option of rethinking this from the bottom up as a television

production, there are some things that we could do which would improve

it, rather than just sticking cameras on it regardless of how

sophisticated we

have become in that technique.

BD: Then would it

lose something for the people

watching it live in the theatre?

RW: Yeah,

absolutely. But you know you get entirely

different values when the show is done on television. Abelard and

Heloise, an opera I did a couple years ago, was actually

televised by the South Carolina television. They have a

very fine director there, and some of the scenes were taken of the

stage performance. They could focus on two faces so the

impact is colossal, and there is no way on stage you are ever

going to get that for an audience of 2,500 people.

BD: This excites

you as a composer, to be able to direct the

interest and the attention of the audience?

RW: Sure,

absolutely, just as your big,

massive scenes never really come off on television. They are

always

kind of contrived. It’s a

medium that can get that other impact.

BD: Would your

operas not work in CinemaScope?

RW: In the movies

you can do both. You can enlarge

all of the intimate scenes onto the screen and that works, but you also

can get these vast kinds of crowd scenes and so forth. You

have the best of all worlds there. Before I had

ever written an opera, when I was a student at the Eastman School, I

had always wanted to write an opera. This was in the thirties

when the first big sound movies were coming

out and the big musicals were done. I frankly thought that

just as drama had been drying up all over the country and the movies

were taking over, the same thing was going to happen with opera

because the sound was getting not too bad, and they could put those

lavish, big Hollywood orchestras on things. I even

knew the show that I wanted to do at that time, Maxwell Anderson’s

Winterset, and I

thought, “Gee,

that would be marvelous.”

I still think would make a tremendous opera, but you can’t get the

rights on this. A whole bunch of us have wanted to. Leonard

Bernstein

wanted it and I tried, but Maxwell Anderson thought of this as his

great

poetic drama, and he would never want a word of it touched. Well,

you couldn’t do the whole work, so I gave up

the whole idea. Then the war came and it wasn’t

until about five years after the war that Douglas Moore — who

was a great

friend and helped me greatly in my early years — asked

me one day. He

said, “Bob, have you ever thought of doing an opera?” because he knew

songs of mine and my orchestral music. I said, “Yes I have,

but I don’t know.” He said I really ought to. At that time

they had the Columbia

Workshop, which was really the first place that gave American composers

a chance in this country. So it was out of that that I went for

the first opera.

BD: I’m glad you

got that opportunity. [Both chuckle]

*

* *

* *

BD: Is opera

art or is opera

entertainment?

RW: Well, I tell

you, it’s lousy opera if it isn’t both. To me there’s never any

conflict between the two. “Entertainment”

is probably the

wrong word. What it really has to be is something that the minute

that the curtain goes up — or the lights come on

if it’s a movie — that

engrosses you and keeps you with it to the end. If it is,

this can be serious or very tragic, and it can have a great social

message. But the important thing is that it simply holds you

with it and communicates what it has to say with its full impact.

That’s entertaining to me.

BD: What is the

role of the critic, or what should it be?

BD: What is the

role of the critic, or what should it be?

RW: I think that

we need to learn that you cannot possibly hear a major, serious opera

or music-theatre piece once and judge it. You will

get certain impressions from it, but you

really can’t criticize it. I’ve known of no one who can.

I’m not talking about a

musical here, where the records have come out

beforehand and people have had a chance to get the music a bit, and the

story is pretty transparent.

BD: Should grand

opera then go to the trouble of putting out a

cast album first?

RW: It would be a

great idea, but it’s a very costly

business. There simply isn’t that kind of potential money in

it.

BD: Where is opera

going today?

RW: There is this

kind of merging which we have going on,

where in a way opera is going to Broadway and the musical theatre is

coming into the opera house. I think we are going through a

period when a number of important things are happening. The idea

that Broadway is profitable just ain’t the truth anymore!

You listen to Hal Prince bitterly complaining, “I’m getting out of

Broadway; you can’t do anything there!” [See my Interview with Hal Prince.]

One of the reasons for this

is the business of producing on Broadway, particularly if you do it on

that kind of lavish scale, is so costly, that you can no longer afford

the failures. That side of the musical theatre is now becoming

non-profit essentially. Meanwhile opera companies, by absorbing

some of the great, standard Broadway musicals into

their repertory are finding that they are developing new

audiences. If they don’t get silly and

feel that they have to produce these things on a sort of Hal Prince

level, they can have some pretty great successes and even make some

money. Not great amounts, but for instance the Houston Opera had

such a great success with Porgy and

Bess that they had to cut it off

from the main opera company into a separate company because it was a

profit-making venture. In order to get that profit back in, they

had to let it be that, and then the profits could go back to the main

opera house. So we are at a very funny transitional stage

here. But I have no sense of pessimism about

it. I think that we have a whole great cultural tradition here,

and I see it only getting better.

BD: There is a

trend among music historians to go back to

original texts. People get material out of

the wastebasket and put it on and hold it up as great

stuff. How do you feel about your own works being subjected to

this type of thing?

RW: If I’ve

revised a work it’s because I thought

something was the matter with it in the first version, and I don’t want

anyone picking up that stuff and sticking it back in. If any of

this material is any good, I’ll find a way to use

it in some other work. As a matter of fact, there are two scenes

in the original Lady from Colorado

where the music was fine but they

were wrong for the show. So we took them out, but I wasn’t going

to throw away

that good stuff. Then when I wrote a saxophone concerto a couple

of years ago, it wound up there. It’s a

very good tradition. Bach did it, Handel did it, Rossini did it,

even Verdi did it.

BD: So the

musicologists are completely on the wrong track

in trying to get the original versions of things?

RW: If there are

versions that were put aside by

the composers themselves, I think yes.

BD: Does the real

future of opera lie in the

smaller productions all around the country rather than at the big three

opera houses?

RW: I do think

that if the big three opera

houses were simply to take on these shows, suddenly everyone would

imitate them. To give you an example,

about twenty years ago, a few of the major conductors began to suddenly

do all the Mahler symphonies. Now these

symphonies are done by every orchestra in the country

just because the New York Philharmonic and the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra and the Boston Symphony

did them. There is a great sense of following after

these things; they set a kind of pattern, and we need this. I

remind Ardis Krainik every time I see her, and she’s trying to do

something which was certainly not done previously there. [See my Interview with Ardis

Krainik.] You’re always likely to get greater

adventure on account of the smaller companies where they can do that

kind of thing much better. It gets those companies a place

in the sun which simply repeating another performance of the standard

repertory won’t achieve, and it provides an excitement in their life

which is not the big-star kind of thing. I listen to those Met

broadcasts, and every time one of the great stars really massacres an

aria or was wobbling all over the place, the audience still goes

wild. I can’t believe my ears; what are they listening to that

they do this? The fact

is all they are doing is applauding themselves for being in that place

when that great, famous person is making that noise up there... and it

is

noise, some of it.

BD: Thank you

so very much for coming to Chicago, and for spending time with me this

afternoon.

RW: It was my

pleasure. Thank you.

=====

===== ===== =====

-- -- --

===== ===== ===== =====

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This is the first of two conversations with Robert Ward.

This interview was recorded at the home of Alan Stone,

Founder and Artistic Director of the Chicago Opera Theater, on May 20,

1985.

Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNIB three days later, and again in 1986, 1987, 1992, and

1996. A copy of the unedited

audio was placed in hte Archive of

Contemporary Music at Northwestern

University, and in the Oral

History American Music Collection at Yale University. This

transcription was

made and posted on this

website in 2012. [Note: The second interview was

done at his hotel in Evanston, Illinois, in February of 2000.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on both WNUR and

Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2010, and also was given to

Yale.]

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Robert Ward: Over

the years since The Crucible

was first performed, a number of people have asked me if there was a

reduced version of the orchestra, because they were operating in

smaller theaters or they had a very small pit. That idea actually

has always appealed to me for the simple reason that because of the

rather intense dramatic nature of the libretto, The Crucible in

fact fares better, I feel, in a small theatre where those values can

come through better than it does in some of the vast houses in which so

much opera takes place in today. So that when Alan Stone of the

Chicago Opera Theater approached me

on this, it came at a time when I was not under a terrible deadline

to get some piece finished, and I felt the moment

was kind of right. One of the reasons that it was right was

that I had heard such very good reports of the productions which were

done here with his group that I decided this was the right

moment for it. So I undertook it for that reason.

Robert Ward: Over

the years since The Crucible

was first performed, a number of people have asked me if there was a

reduced version of the orchestra, because they were operating in

smaller theaters or they had a very small pit. That idea actually

has always appealed to me for the simple reason that because of the

rather intense dramatic nature of the libretto, The Crucible in

fact fares better, I feel, in a small theatre where those values can

come through better than it does in some of the vast houses in which so

much opera takes place in today. So that when Alan Stone of the

Chicago Opera Theater approached me

on this, it came at a time when I was not under a terrible deadline

to get some piece finished, and I felt the moment

was kind of right. One of the reasons that it was right was

that I had heard such very good reports of the productions which were

done here with his group that I decided this was the right

moment for it. So I undertook it for that reason.

BD: I

look forward to this new production very much.

BD: I

look forward to this new production very much.

BD: As the world

keeps getting faster and faster and everything

becomes micropressed and microchipped, supposed two hundred years from

now some composer of operas that are in vogue that run 42 minutes

each says, “We should take the operas of Robert Ward and

condense them into the 42 minute length.” What do you say to

that?

BD: As the world

keeps getting faster and faster and everything

becomes micropressed and microchipped, supposed two hundred years from

now some composer of operas that are in vogue that run 42 minutes

each says, “We should take the operas of Robert Ward and

condense them into the 42 minute length.” What do you say to

that?  RW: Yes, that was

the Pinza role. On the other hand, an opera singer is not going

to

do Bloody Mary very well. You’ve got to have

someone that can belt that thing out in Broadway style. These are

two entirely different ways of approaching vocal projection, and

so you have to deal with these things very separately. Those

are the nuts and bolts that you can’t deny if you’re going to do

this. I was at the rehearsals of Sweeney Todd

at the New York City Opera, and it was very interesting because

suddenly you had everything turned around there. In the Broadway

production, you had Broadway singers who had this heavy middle register

that they can belt things out, and they’re very shaky up on the

top. The composers have to write the top notes very carefully for

them. They

were miked up over a very small orchestra, but a rather

brash, loud orchestra. Suddenly, when New York City Opera did it,

they

had opera singers who had all the top notes, but they couldn’t belt out

those middle notes. They couldn’t sing anything else for weeks if

they

did. They also decided that they would use their full orchestra,

and it sounded like quagmire of mud down in the pit there. It

lost all of the brilliance and the sharpness of a Broadway

orchestra. You couldn’t hear the singers then over this, and so

then they ultimately miked it up somehow in order to

get the singers through. And it was in this huge hall where you

lost the visual context. So suddenly everything wasn’t quite

right about this. It isn’t that it’s not a great show

— it is — but you have to put things

in the right place.

RW: Yes, that was

the Pinza role. On the other hand, an opera singer is not going

to

do Bloody Mary very well. You’ve got to have

someone that can belt that thing out in Broadway style. These are

two entirely different ways of approaching vocal projection, and

so you have to deal with these things very separately. Those

are the nuts and bolts that you can’t deny if you’re going to do

this. I was at the rehearsals of Sweeney Todd

at the New York City Opera, and it was very interesting because

suddenly you had everything turned around there. In the Broadway

production, you had Broadway singers who had this heavy middle register

that they can belt things out, and they’re very shaky up on the

top. The composers have to write the top notes very carefully for

them. They

were miked up over a very small orchestra, but a rather

brash, loud orchestra. Suddenly, when New York City Opera did it,

they

had opera singers who had all the top notes, but they couldn’t belt out

those middle notes. They couldn’t sing anything else for weeks if

they

did. They also decided that they would use their full orchestra,

and it sounded like quagmire of mud down in the pit there. It

lost all of the brilliance and the sharpness of a Broadway

orchestra. You couldn’t hear the singers then over this, and so

then they ultimately miked it up somehow in order to

get the singers through. And it was in this huge hall where you

lost the visual context. So suddenly everything wasn’t quite

right about this. It isn’t that it’s not a great show

— it is — but you have to put things

in the right place. BD: What is the

role of the critic, or what should it be?

BD: What is the

role of the critic, or what should it be?