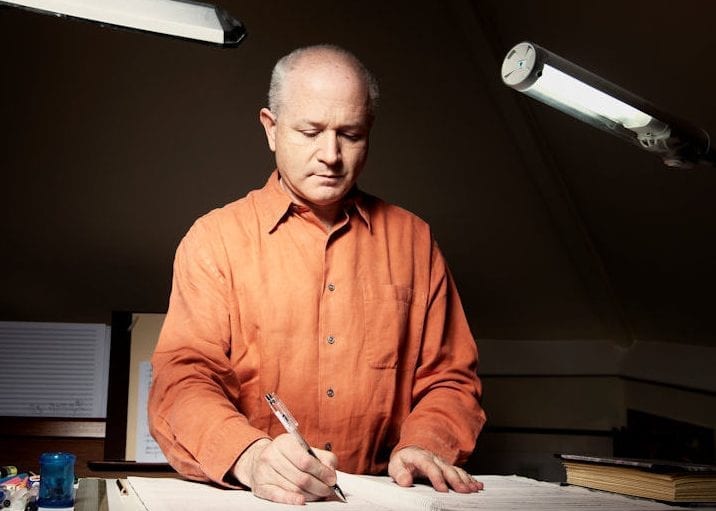

| Born in 1960, George Benjamin began composing at the age of seven. In 1976 he entered the Paris Conservatoire to study with Messiaen, after which he worked with Alexander Goehr at King's College, Cambridge.

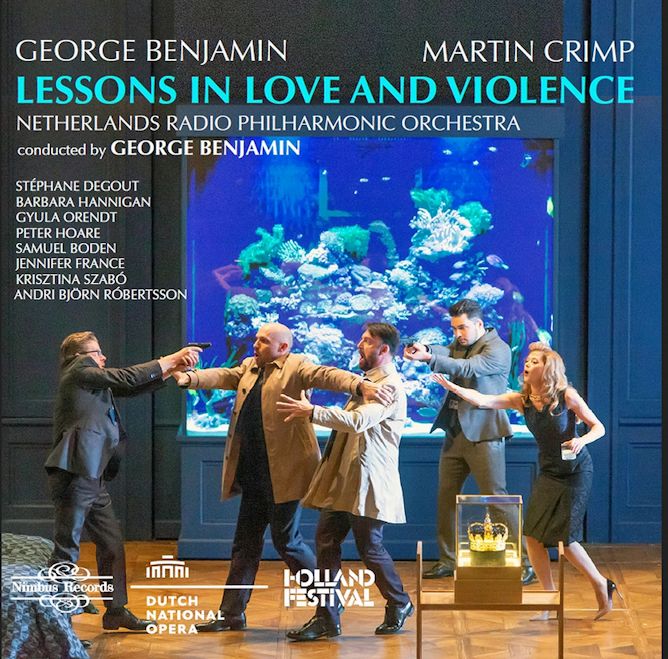

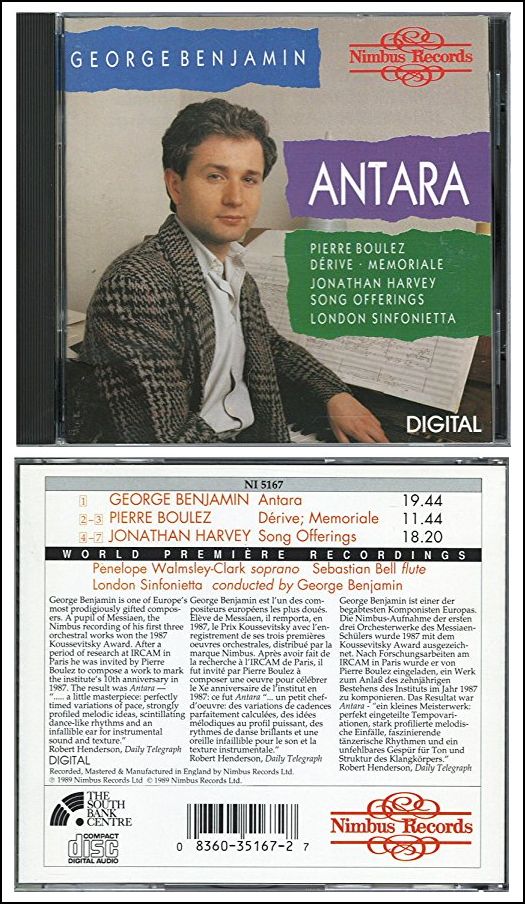

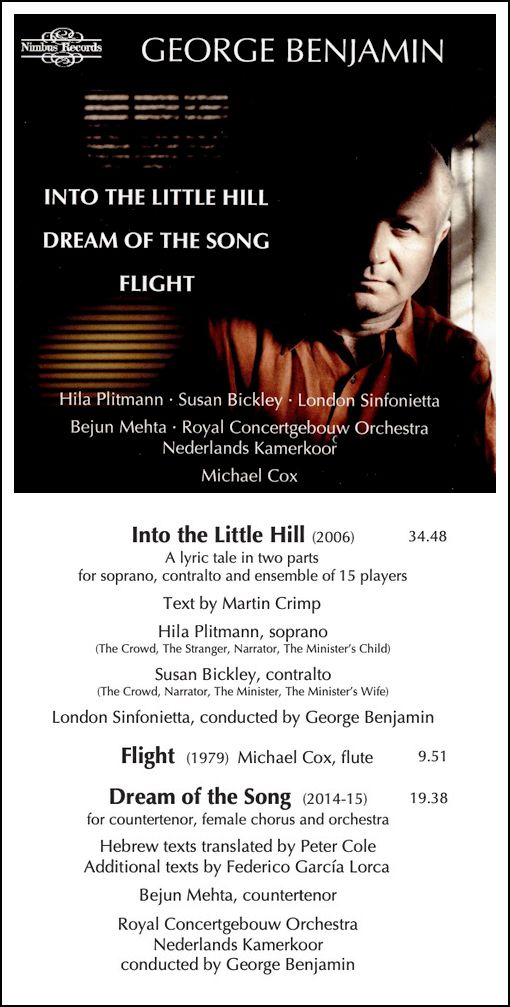

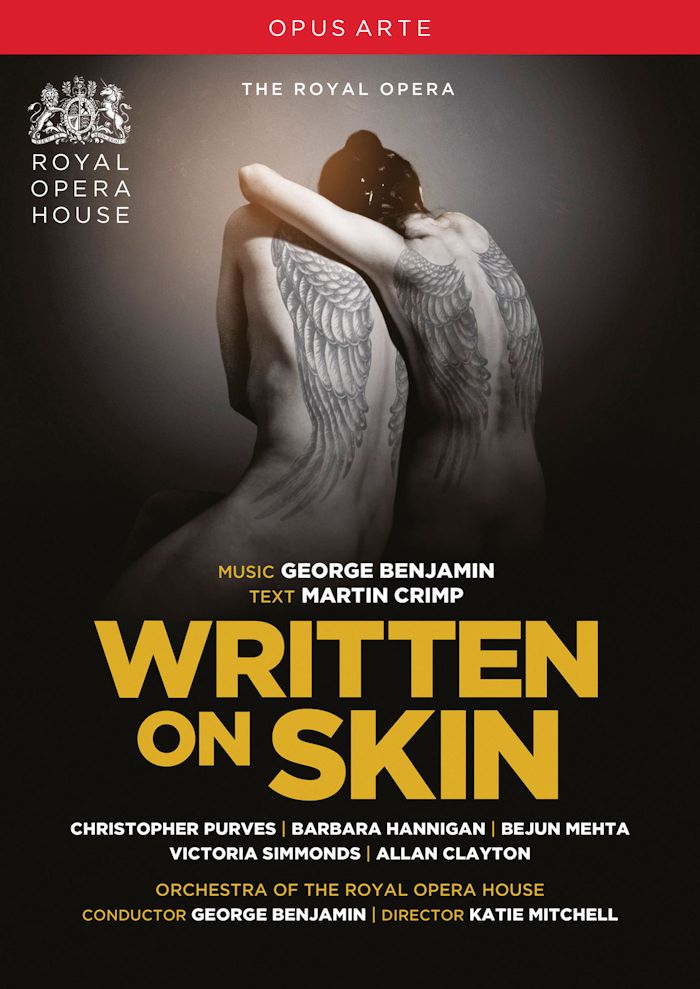

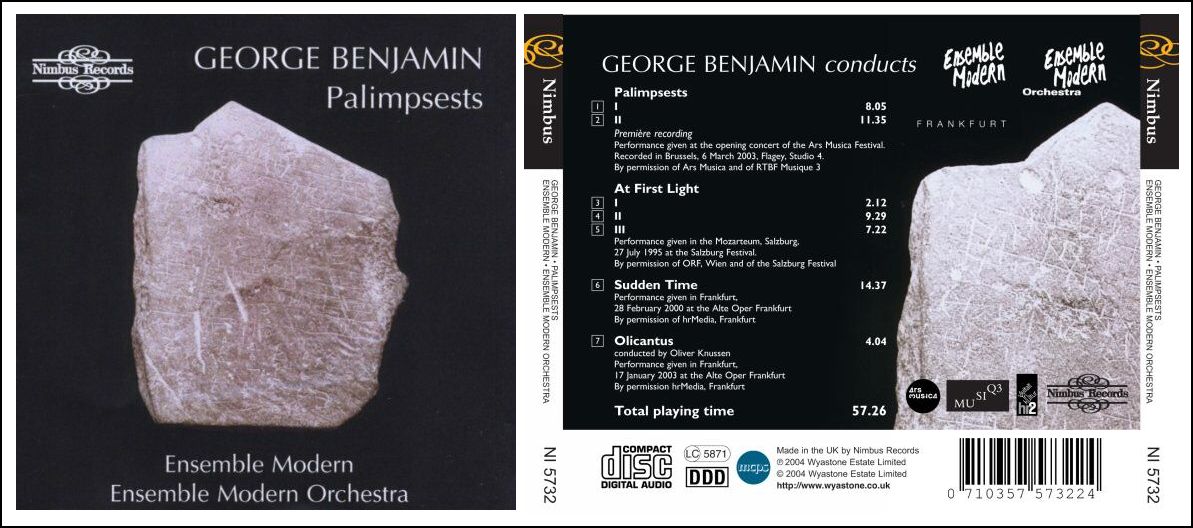

Benjamin’s first operatic work Into the Little Hill, written with playwright Martin Crimp, was commissioned in 2006 by the Festival d'Automne in Paris. Their second collaboration, Written on Skin, premiered at the Aix-en-Provence festival in July 2012, has since been scheduled by over 20 international opera houses, winning as many international awards. Lessons in Love and Violence, a third collaboration with Martin Crimp, premiered at the Royal Opera House in 2018; both works were filmed by BBC television, and a related ‘Imagine’ profile on Benjamin was broadcast on BBC1 in October 2018. As a conductor Benjamin has a broad repertoire - ranging from Mozart and Schumann to Knussen, Murail and Abrahamsen - and has conducted numerous world premieres, including important works by Rihm, Chin, Grisey and Ligeti. He regularly works with some of the world's leading orchestras, and over the years has developed particularly close relationships with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, London Sinfonietta and Ensemble Modern as well as the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, who gave the world premiere of Dream of the Song in September 2015. During the 2018-19 season Benjamin was composer-in-residence with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Musikfest and at the new Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. Recent awards include the 2015 Prince Pierre of Monaco composition

prize (for Written on Skin) and the 2019 Golden Lion Award for

lifetime achievement from the Venice Biennale. An honorary fellow of King’s

College Cambridge, the Guildhall, the Royal College and the Royal Academy

of Music, Benjamin is also an Honorary Member of the Royal Philharmonic

Society. He was awarded a C.B.E. in 2010 and made an Commandeur de l’Ordre

des Arts et des Lettres in 2015, and was knighted in the 2017 Queen's

Birthday Honours. He has frequently taught and performed at the Tanglewood

Festival over the last 20 years, and since 2001 has been the Henry Purcell

Professor of Composition at King’s College, London and was made a Fellow

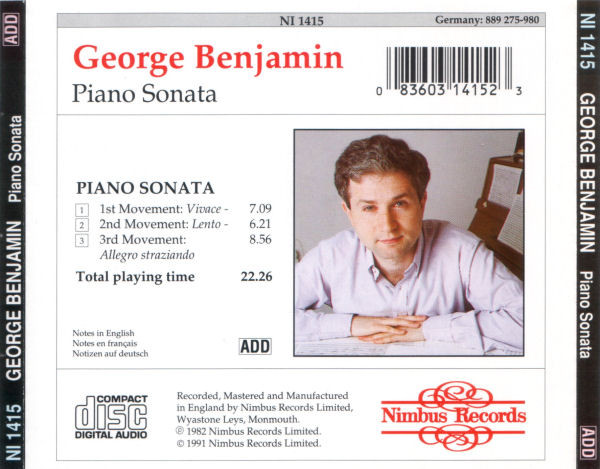

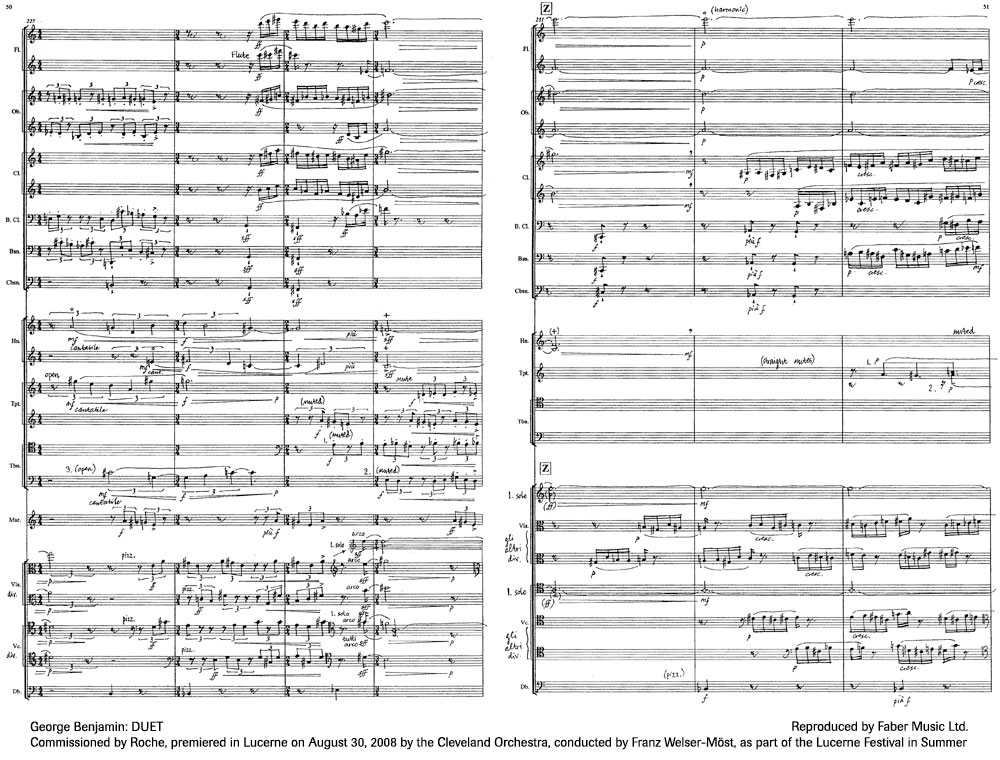

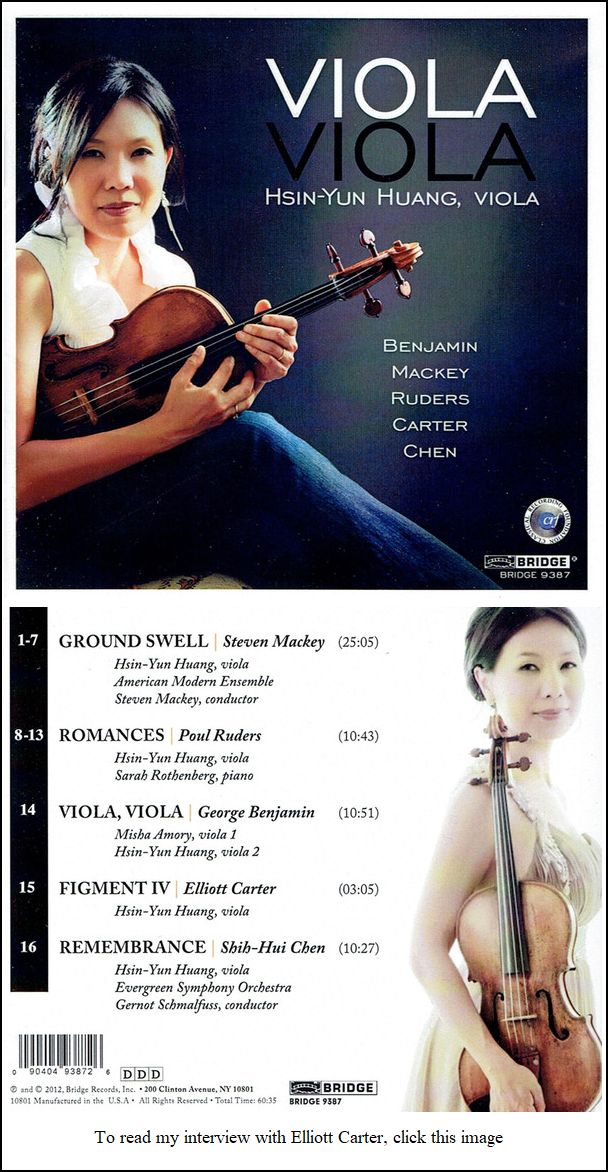

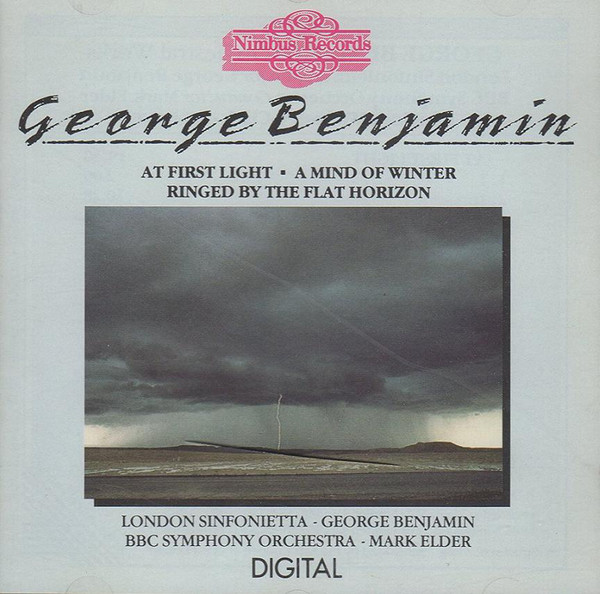

of the College in 2017. His works are published by Faber Music and are recorded

on Nimbus Records. Benjamin was elected as a member of the Royal Swedish

Academy of Music in 2018.

== Biography from the website of his publisher,

Faber Music

== Names which are links in this box refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

BD: There’s

no time that you remember when you were not involved in music?

BD: There’s

no time that you remember when you were not involved in music?|

Nicolas de Grigny was born in 1672 in Reims in the parish of Saint-Pierre-Le-Vieil. The exact date of his birth is unknown; he was baptized on 8 September. He was born into a family of musicians: his father, his grandfather, and his uncle, Robert, were organists at the Reims Cathedral, the Basilica of St. Pierre and St. Hilaire, respectively. Few details about his life are known, nothing at all about his formative years. Between 1693 and 1695 he served as organist of the abbey church of Saint Denis, in Paris (where his brother André de Grigny was sub-prior). It was also during that period that Grigny studied with Nicolas Lebègue, who was by then one of the most famous French keyboard composers. In 1695 Grigny married Marie-Magdeleine de France, daughter of a Parisian merchant. Apparently, he returned to his hometown soon afterwards: the record of the birth of his first son indicates that de Grigny was already in Reims in 1696. The couple went on to produce six more children. By late 1697 Grigny was appointed titular organist of Notre-Dame de Reims (the exact date of the appointment is not known), the city's famous cathedral in which French kings were crowned. In 1699 the composer published his Premier livre d'orgue [contenant une messe et les hymnes des principalles festes de l'année] in Paris. Grigny died in 1703, aged 31, shortly after accepting a job offer from Saint Symphorien, a parish church in Reims. His Livre d'orgue was reissued in 1711 through the efforts of his widow. The collection became known abroad: it was copied in 1713 by Johann Sebastian Bach. |

BD: You’re both composer and teacher. How do

you divide your time between those two very taxing activities?

BD: You’re both composer and teacher. How do

you divide your time between those two very taxing activities? Benjamin: Yes, drastically, because

if you have the same attitude as you’d have when you were writing, you

would be quite useless as a conductor. The first purpose of the

conductor is to give time and organization to a performance, the backbone

of which is rhythm. For that, you need to listen and to receive from

the musicians, and give, and give, and give back. I can hear my new

piece in my head virtually perfectly, and I’m the only person who has heard

it up to now. So if you’re completely locked

in your head, that’s not the same as conducting it and performing it.

Therefore, to go from the state that I have it in my head, to the state

of performing it, requires a complete change of philosophy. You

have to serve the music when you’re conducting it. It mustn’t be

stuck inside your head. On the contrary, you’re

giving it to an audience, and you’re responding to the musicians in front

of you, so that needs an entirely different approach. It’s actually

very hard to finish a piece, and conduct it two weeks later. That’s

very hard, very, very hard.

Benjamin: Yes, drastically, because

if you have the same attitude as you’d have when you were writing, you

would be quite useless as a conductor. The first purpose of the

conductor is to give time and organization to a performance, the backbone

of which is rhythm. For that, you need to listen and to receive from

the musicians, and give, and give, and give back. I can hear my new

piece in my head virtually perfectly, and I’m the only person who has heard

it up to now. So if you’re completely locked

in your head, that’s not the same as conducting it and performing it.

Therefore, to go from the state that I have it in my head, to the state

of performing it, requires a complete change of philosophy. You

have to serve the music when you’re conducting it. It mustn’t be

stuck inside your head. On the contrary, you’re

giving it to an audience, and you’re responding to the musicians in front

of you, so that needs an entirely different approach. It’s actually

very hard to finish a piece, and conduct it two weeks later. That’s

very hard, very, very hard. BD: Is it its own world?

BD: Is it its own world?

BD: When you’ve married the ideas

to the structure, is it always the piece that you want?

For instance, if you’re trying to write an orchestral piece, would these

ideas, perhaps, go better as a clarinet sonata?

BD: When you’ve married the ideas

to the structure, is it always the piece that you want?

For instance, if you’re trying to write an orchestral piece, would these

ideas, perhaps, go better as a clarinet sonata?

Benjamin: No, I’m afraid. It depends which piece.

Some are more difficult than others. I’m sometimes not at all

happy with the ones I do myself, and sometimes overawed by the wonderful

ones that I’ve had by great musicians that have done my work. I’m

thinking of recent performances I’ve had by Pierre Boulez, or Oliver

Knussen, or Kent Nagano, or David Robertson, who did fantastic performances.

But I’ve also suffered, as every composer has always suffered, from

some terrible performances. To get over it, after having to sit

through your piece when it’s being massacred on stage, note by note,

every second feels like it’s half an hour, and you want to get up and say,

“This is not me! Please don’t listen to this!

This is not what I wrote! I didn’t write this! This is not the

way it’s meant to go!” [Both laugh]

Benjamin: No, I’m afraid. It depends which piece.

Some are more difficult than others. I’m sometimes not at all

happy with the ones I do myself, and sometimes overawed by the wonderful

ones that I’ve had by great musicians that have done my work. I’m

thinking of recent performances I’ve had by Pierre Boulez, or Oliver

Knussen, or Kent Nagano, or David Robertson, who did fantastic performances.

But I’ve also suffered, as every composer has always suffered, from

some terrible performances. To get over it, after having to sit

through your piece when it’s being massacred on stage, note by note,

every second feels like it’s half an hour, and you want to get up and say,

“This is not me! Please don’t listen to this!

This is not what I wrote! I didn’t write this! This is not the

way it’s meant to go!” [Both laugh][Let me say here, once again, that even though I have collected recordings all my life, and for a quarter century I made my living as an announcer/producer

with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, I have always stated, both publicly and privately, that the real music is in the live concert.]

© 2005 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 18, 2005. Portions were broadcast on WNUR the following month, and again in 2008 and 2017; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2005, 2008, and 2015. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.