|

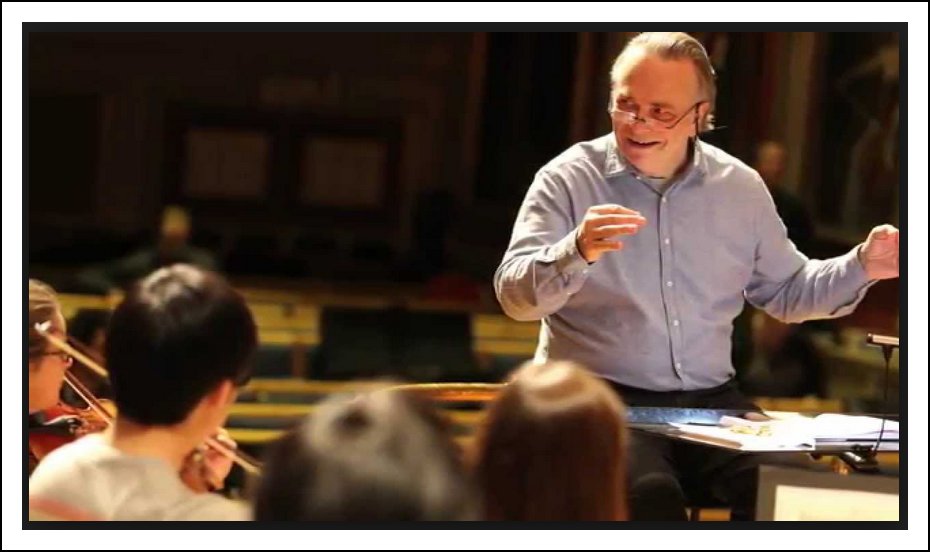

Mark Elder (Conductor)

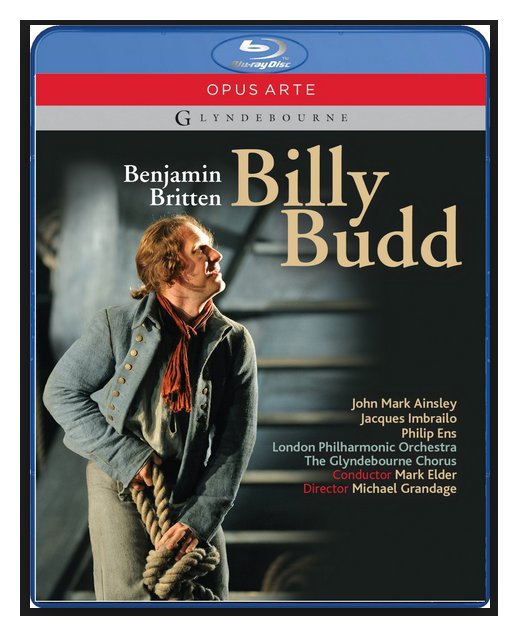

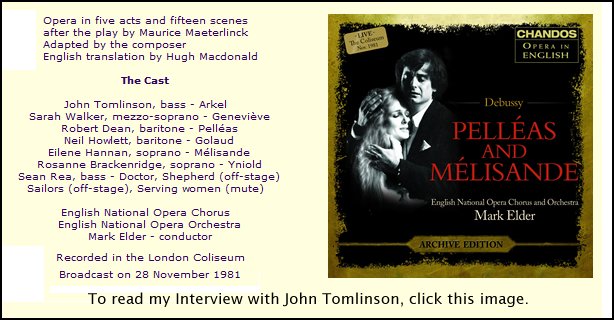

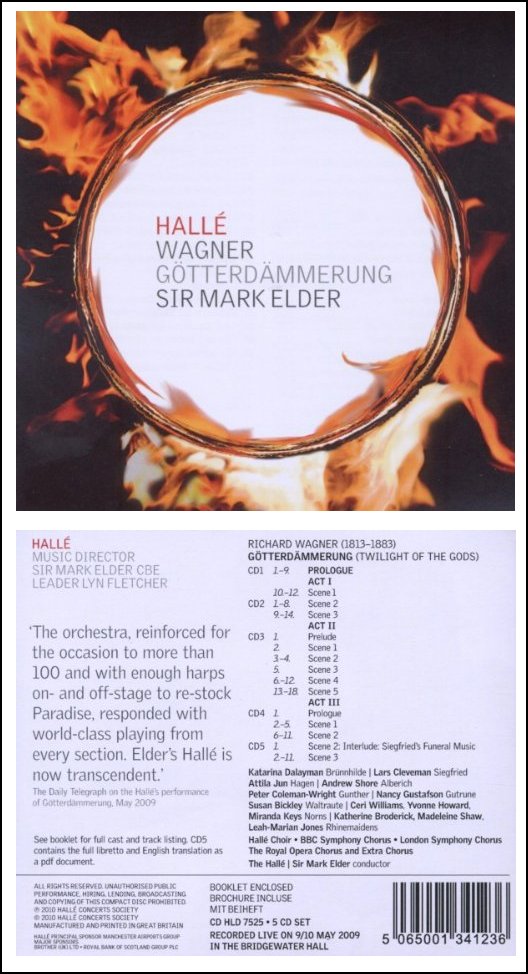

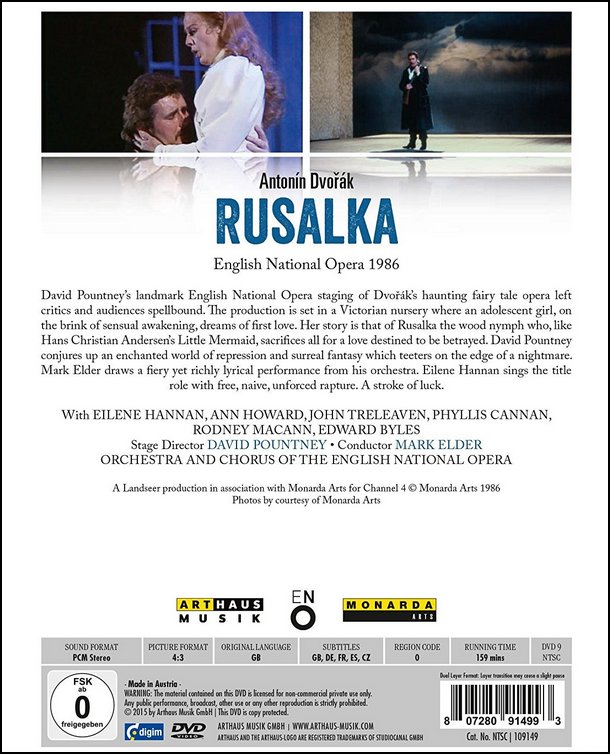

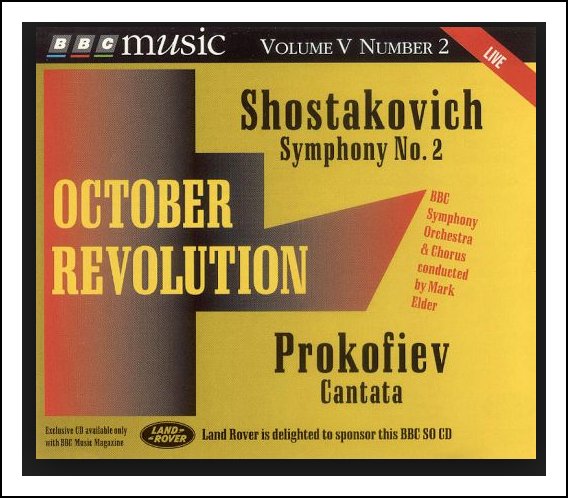

Born: June 2, 1947 - Hexham, Northumberland, England The English conductor, Mark Philip Elder, is the son of a dentist. As a youth he divulged talent both as a singer and instrumentalist, serving as a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral and as the first-chair bassoonist in the National Youth Orchestra. He studied music at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he studied music and was a choral scholar. He was later mentored by renowned British conductor and musicologist Edward Downes. Elder worked briefly in minor capacities at Glyndeboune and Covent Garden before gaining experience conducting Verdi operas as a regular conductor at the Sydney Opera House, Australia from 1972 to 1974. He returned to England in 1974. Elder has achieved wide acclaim in the realm of opera, but has also generally devoted an equal share of his career to orchestral work. He perhaps made his strongest impression at the English National Opera (ENO), where he began conducting regularly from 1974. He was the music director of the ENO from 1979 to 1993, and was known as part of the "Power House" team that also included general director Peter Jonas and artistic director David Pountney, and which gave ENO several very successful years of productions. During his 15 years as ENO director, he conducted the company in numerous highly acclaimed productions and led successful tours to the USA, Russia, and other parts of Europe. Elder has also conducted at Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, the Sydney Opera House, the Chicago Lyric Opera. He appears frequently in many of the most prominent international opera houses, including Covent Garden, the Metropolitan Opera New York, and the Opéra National de Paris and was the first British conductor to conduct a new production at the Bayreuth Festival. Mark Elder held positions as Principal Guest Conductor of the London Mozart Players from 1980 to 1983, and of the BBC Symphony Orchestra from 1982 to 1985. He also served as Music Director of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra from 1989 to 1994, and as Principal Guest Conductor of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra from 1992 to 1995. In 1999 he was named Music Director of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester. His first concert as Music Director was in October 2000. His proposed novel ideas for concerts have included the abandonment of traditional concert evening garb. Elder is generally regarded as having restored the orchestra to high critical and musical standards, after a period where the continuing existence of the orchestra was in doubt In 2004, he signed a contract to extend his tenure from 2005 to 2008, with an optional two-year extension at the end of that time. In May 2009, the orchestra announced the extension of Elder's contract to 2015. Highlights of the 2009-2010 season, during which Sir Mark Elder celebrates his 10th anniversary with the orchestra, include his and the Hallé’s major role in a complete cycle of Gustav Mahler symphonies marking the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth.  Mark Elder also works regularly with the world’s leading symphony orchestras

and, in the UK, enjoys close associations with both the London Philharmonic

Orchestra and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. In the USA he has enjoyed

a long-standing relationship with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, his most

recent project for whom was a three-week Dvořák Festival in June

2009. He first conducted the Last Night of the Proms in 1987. He was scheduled

to conduct again in 1990, but his remarks about the nature of some of the

traditional Proms selections in the context of the impending first Gulf

War led to his dismissal from that engagement. In 2006, he returned to conduct

the BBC Symphony Orchestra for his second Last Night engagement, a concert

which was internationally televised.

Mark Elder also works regularly with the world’s leading symphony orchestras

and, in the UK, enjoys close associations with both the London Philharmonic

Orchestra and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. In the USA he has enjoyed

a long-standing relationship with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, his most

recent project for whom was a three-week Dvořák Festival in June

2009. He first conducted the Last Night of the Proms in 1987. He was scheduled

to conduct again in 1990, but his remarks about the nature of some of the

traditional Proms selections in the context of the impending first Gulf

War led to his dismissal from that engagement. In 2006, he returned to conduct

the BBC Symphony Orchestra for his second Last Night engagement, a concert

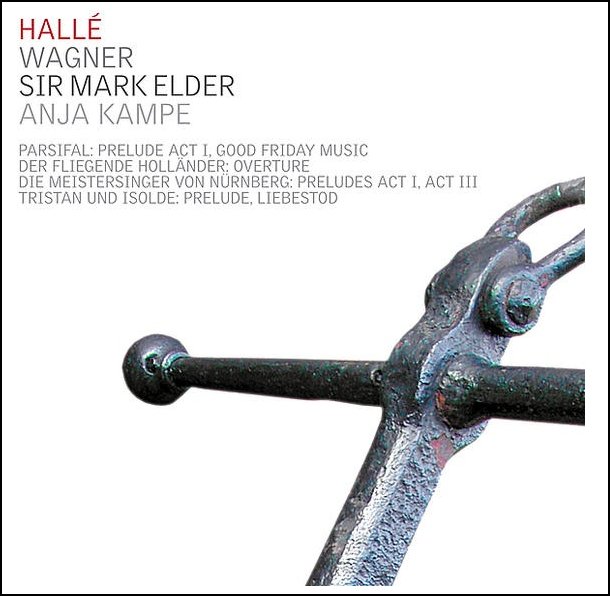

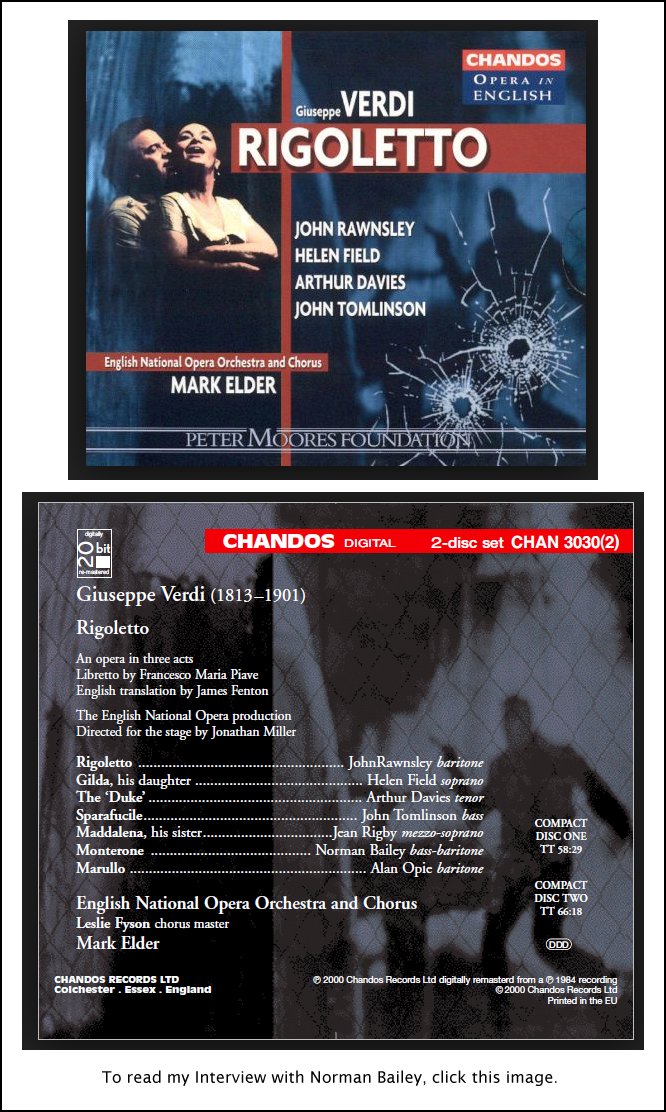

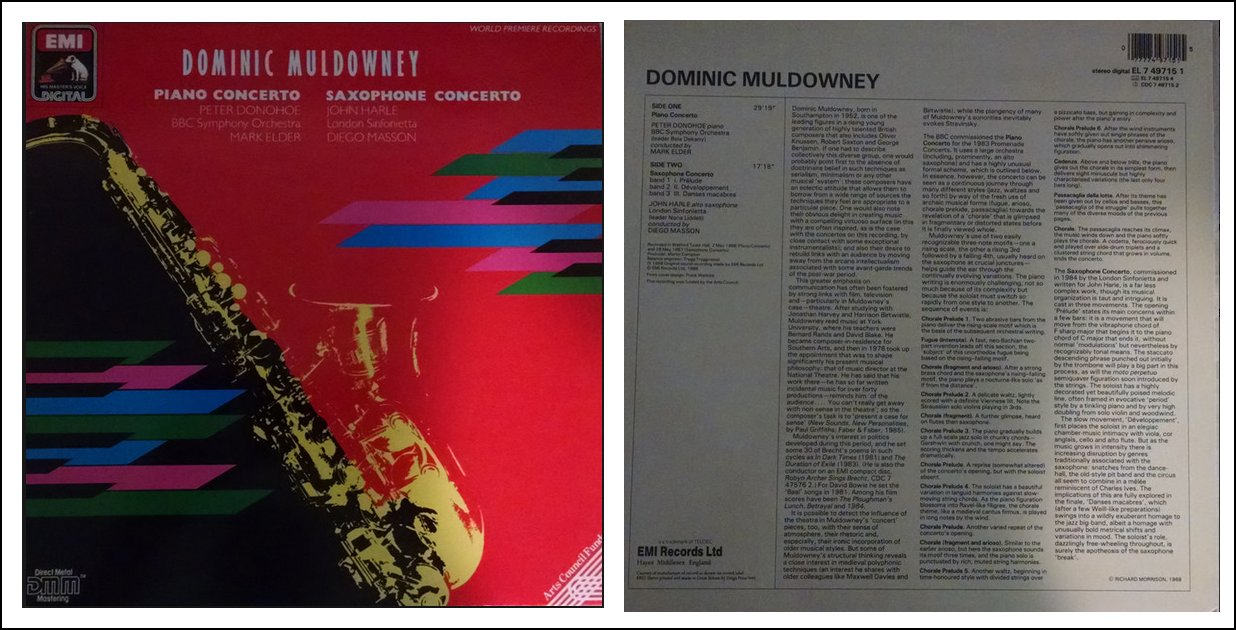

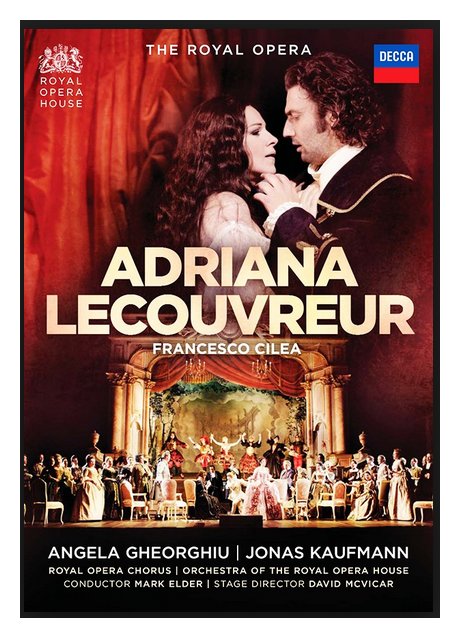

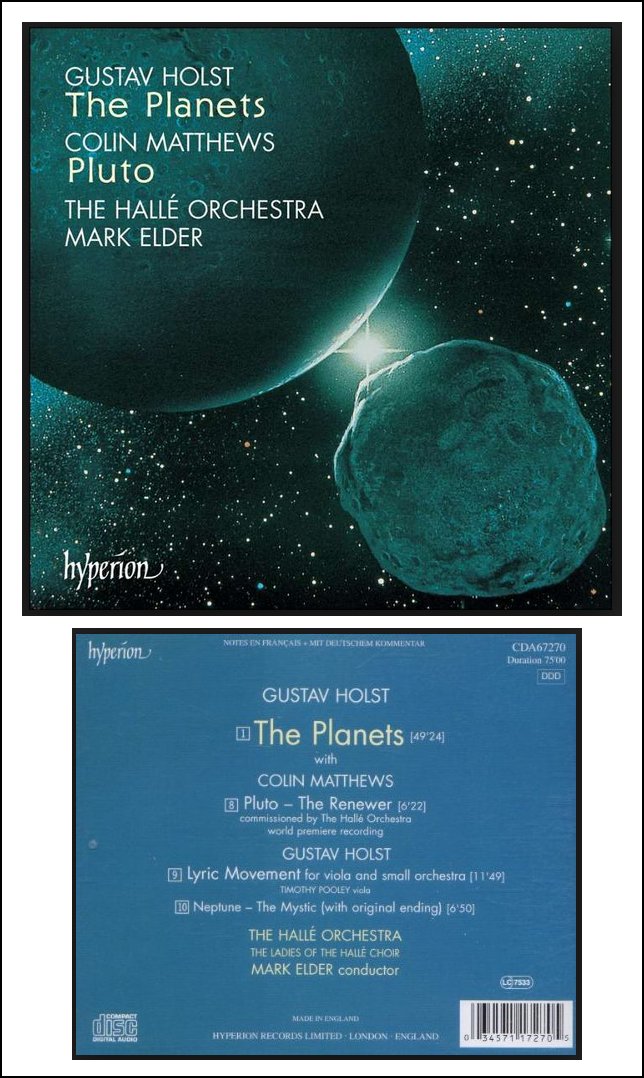

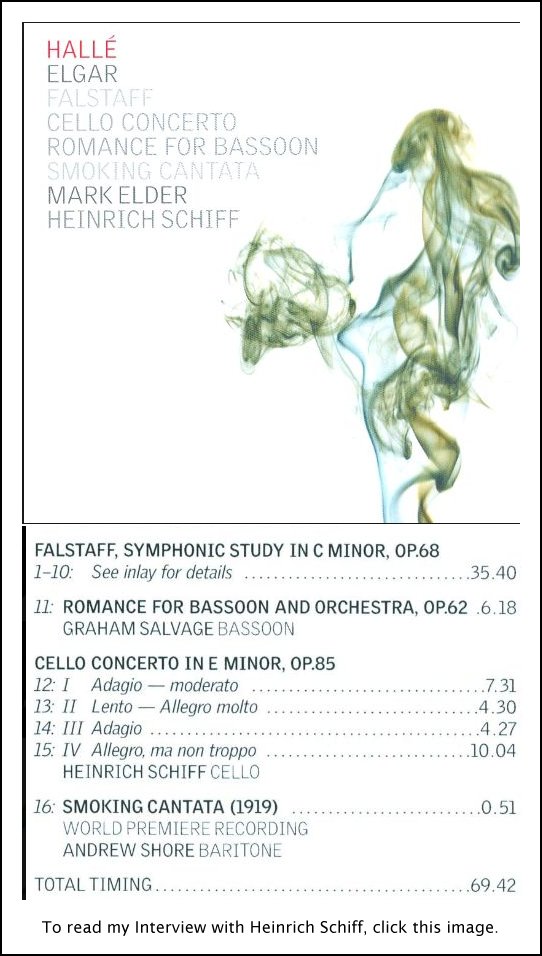

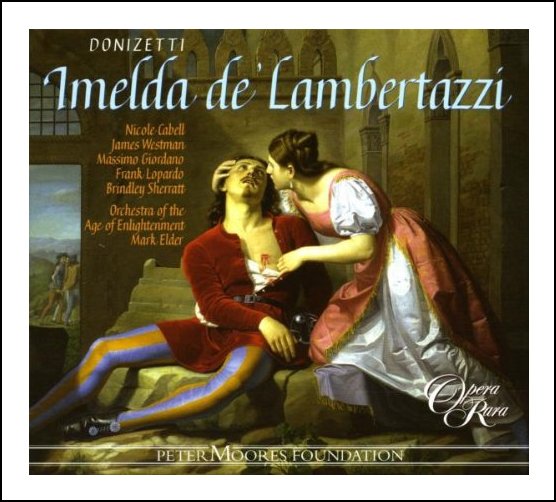

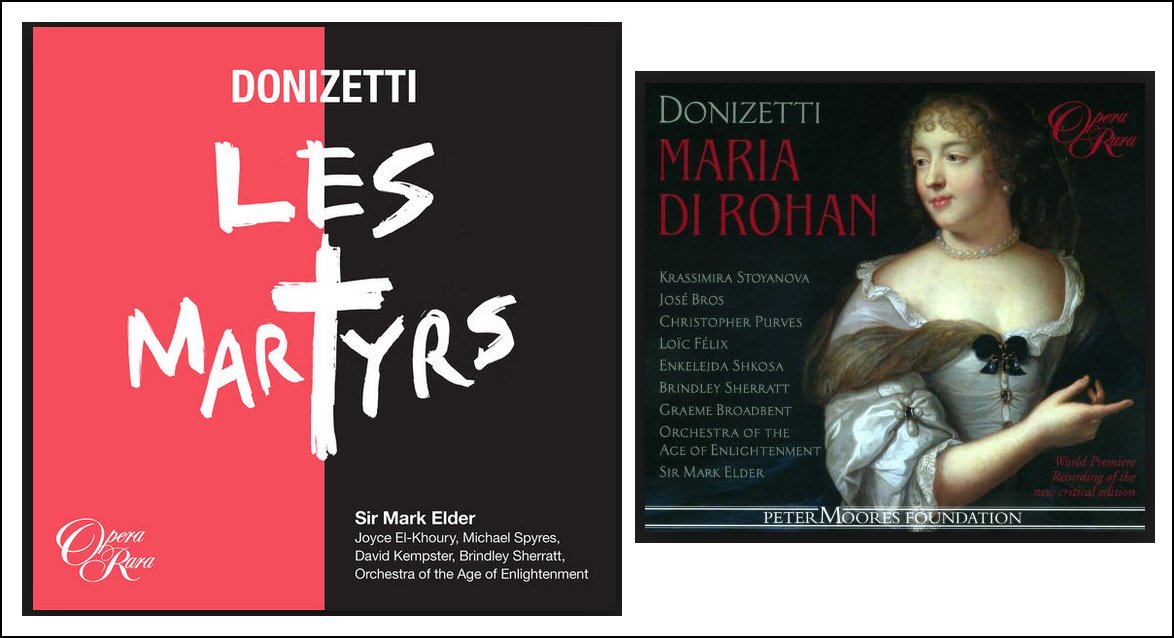

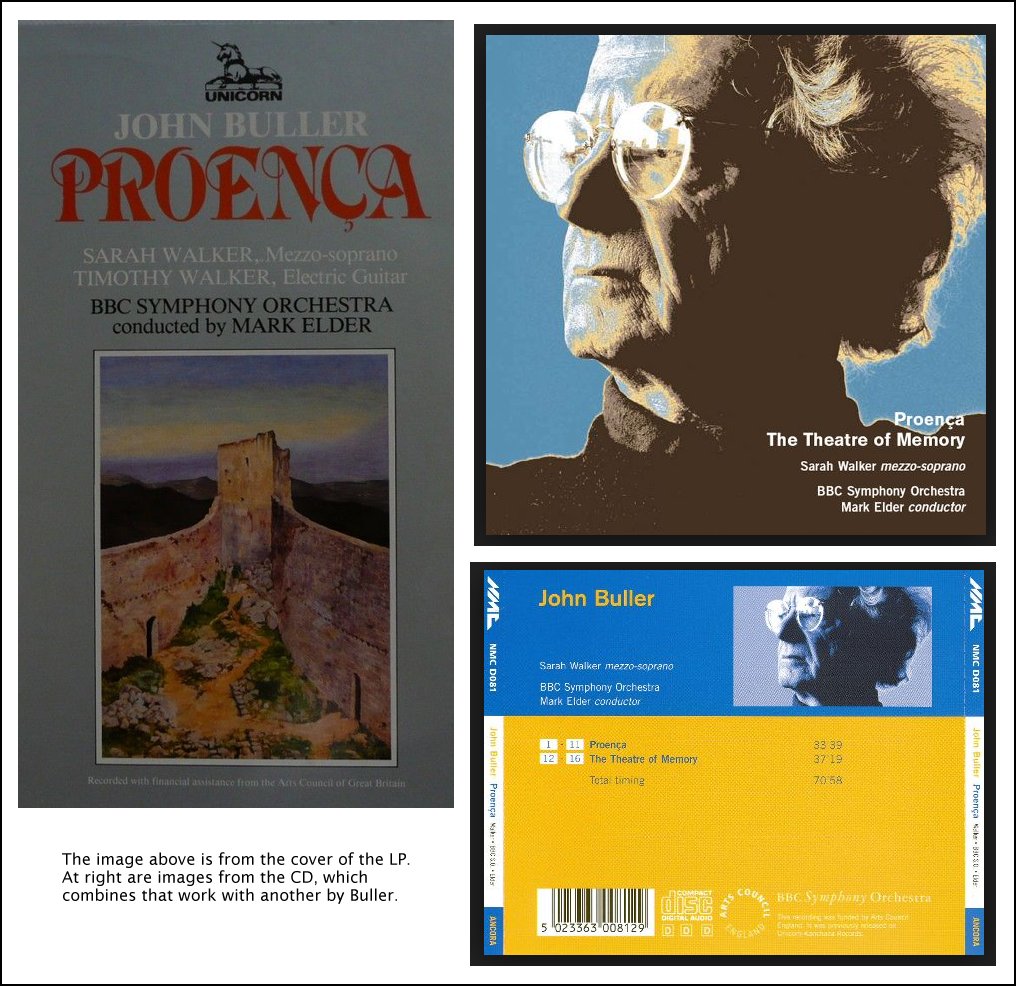

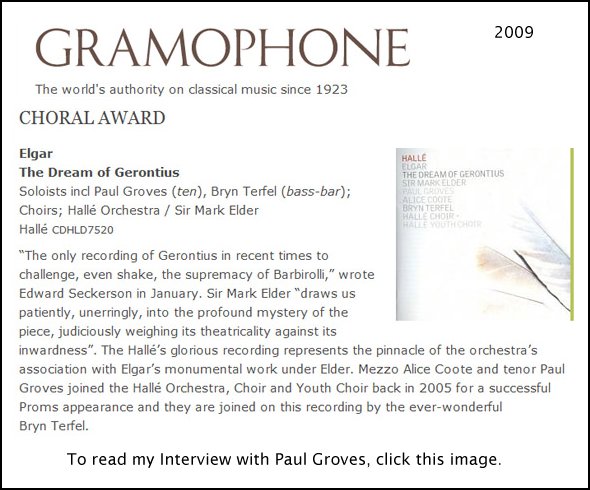

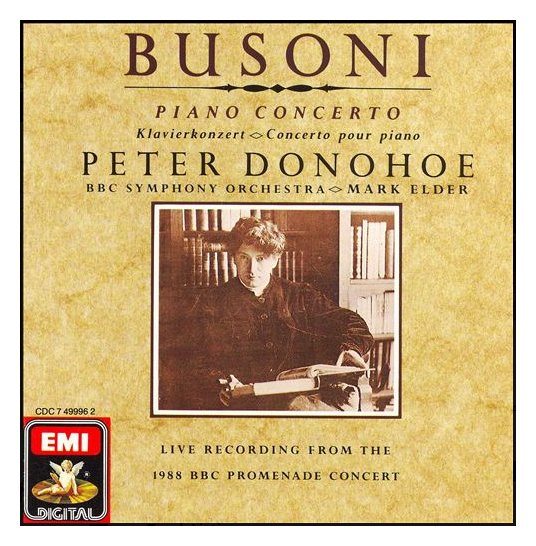

which was internationally televised.His repertory is broad in both the operatic and orchestral realms: though he has favored Verdi in the opera house, he has led performances of Wagner (Die Meistersinger; Parsifal), Ferruccio Busoni (Doktor Faust), Igor Stravinsky (The Rake's Progress), and modern composers like David Blake (Toussaint). His orchestral choices include many standards, while taking in works by modern British composers like George Benjamin, Nicholas Maw, and Jonathan Harvey. Elder has described his own conducting style as follows: "I'm quite a physical conductor. I remember seeing Adrian [Boult] backstage after the 1978 Proms and he was wearing a freshly ironed light blue M&S shirt and he said to me 'I see you're one of the sweaty ones.' He was famously non-perspirational." Mark Elder has made numerous recordings for a variety of labels, including Sony, Chandos, ASV, NMC, Hyperion Glyndebourne record labels, as well as for the Hallé Orchestra's own label. He has made many recordings with orchestras including the Hallé Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Royal Opera House and ENO. Among his more successful recordings are his English-language version of Verdi's Rigoletto on Chandos, issued in 2000, and his 2004 recording of Edward Elgar's Symphony No. 2 on ASV. He has been involved in several TV projects including a film on the life and music of Verdi for BBC TV and a similar project on Donizetti for German television. Recent opera recordings include Donizetti’s Dom Sebastien, Imelda di Lambertazzi, Linda di Chamounix and most recently Maria di Rohan for Opera Rara. In addition to his conducting and recording activities, Elder also has written on music for The Guardian and other newspapers. Recent and forthcoming symphonic engagements, apart from his commitment to the Hallé Orchestra, include the Berliner Philharmoniker, Münchner Philharmoniker, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, Russian National Orchestra, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Recent operatic engagements have included Tannhäuser, Mefistofele, Otello, Samson and Madam Butterfly for the Metropolitan Opera New York, Pelléas et Mélisande, Turandot, and Berlioz’ La damnation de Faust for the Opéra National de Paris, King Roger at The Bregenz Festival, The Rake’s Progress, Euryanthe and Fidelio for Glyndebourne, Bataglia di Legnano, La Cenerentola, Attila, Lohengrin, Simon Boccanegra, Turandot, La bohème, Il barbiere di Siviglia, concert performances of Donizetti’s Dom Sebastien and Linda di Chamounix (both also recorded for Opera Rara), Cyrano de Bergerac by Alfano, Stiffelio and Ariadne auf Naxos , Elektra, Capuleti for Covent Garden, Don Carlo in Genova, and Hänsel und Gretel, Un ballo in maschera, Charles Gounod’s Faust for the Lyric Opera Chicago and Il trovatore in Florence. Future operatic engagements include Adriana Lecouvreur and The Tsar’s Bride for Covent Garden, Tannhäuser in Paris and Billy Budd at Glyndebourne. In May 2009 he conducted Götterdämmerung complete in concert with the Hallé Orchestra. Mark Elder was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1989 Queen's Birthday Honours. He won an Olivier Award in 1991 for his outstanding work at English National Opera. He received the 2006 conductor prize of the Royal Philharmonic Society. In April 2007, Elder was one of eight conductors of British orchestras to endorse the 10-year classical music outreach manifesto, "Building on Excellence: Orchestras for the 21st Century", to increase the presence of classical music in the UK, including giving free entry to all British schoolchildren to a classical music concert. In June 2008, Elder received a knighthood in the 2008 Queen's Birthday Honours. -- Text from the Bach Cantatas website.

-- Throughout this webpage, names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

BD: So then there are some

operas which are not worth doing in translation?

BD: So then there are some

operas which are not worth doing in translation? BD:

Then let me ask the ‘capriccio’

question. Which is more important in opera, or which should be more

important in opera, the music or the drama?

BD:

Then let me ask the ‘capriccio’

question. Which is more important in opera, or which should be more

important in opera, the music or the drama? Walter Felsenstein (30 May 1901 – 8 October 1975) was an Austrian theater

and opera director. He was one of the most important exponents of

textual accuracy, and gave productions in which dramatic and musical values

were exquisitely researched and balanced. In 1947 he created the Komische

Oper in East Berlin, where he worked as director until his death.

Walter Felsenstein (30 May 1901 – 8 October 1975) was an Austrian theater

and opera director. He was one of the most important exponents of

textual accuracy, and gave productions in which dramatic and musical values

were exquisitely researched and balanced. In 1947 he created the Komische

Oper in East Berlin, where he worked as director until his death.

Preparations for each new production could last two months or longer. If singers meticulously coached and trained in their parts fell ill, performances were simply canceled. Since the glamorous superstars of the day could never spare the time Felsenstein required, he worked with his own hand-picked troupe of devoted singers, most from Eastern Europe and virtually unknown in the West. Everything was sung in German, usually in his own translations. Whoever wanted to experience this singular operatic mix had to make the pilgrimage to East Berlin, a trip that became even dicier after the wall went up. Together with the Komische Oper troupe he visited the USSR a few times. In Moscow it was stated that his way of the opera staging was similar to the principles of Konstantin Stanislavsky. His most famous students were Götz Friedrich and Harry Kupfer, both of whom went on to have important careers developing Felsenstein's work. |

ME:

No. Well, on one level they are, but I don’t think that that they’re

more or less fascinating than when the opposite was the case. I love

Wagner’s texts actually. I admire them a great deal. I think

Rhinegold, for instance, has a wonderful

text, but I don’t think that the fact that he wrote the libretto means

anything more specific than that. One is dealing with a different

sort of sophistication in writing operas in the theater, but that comes

from his great skill as a librettist, and the fact that Rhinegold, which I mentioned, was the

last libretto to be written of the Ring

and the first music. His control of the libretto by that time was

just wonderful, and the strands in Rhinegold

and the discussions are just fascinating and beautiful and musically controlled

by the poetry.

ME:

No. Well, on one level they are, but I don’t think that that they’re

more or less fascinating than when the opposite was the case. I love

Wagner’s texts actually. I admire them a great deal. I think

Rhinegold, for instance, has a wonderful

text, but I don’t think that the fact that he wrote the libretto means

anything more specific than that. One is dealing with a different

sort of sophistication in writing operas in the theater, but that comes

from his great skill as a librettist, and the fact that Rhinegold, which I mentioned, was the

last libretto to be written of the Ring

and the first music. His control of the libretto by that time was

just wonderful, and the strands in Rhinegold

and the discussions are just fascinating and beautiful and musically controlled

by the poetry. BD:

Stimulation is part of the process?

BD:

Stimulation is part of the process? BD: [Wryly] Did you say ‘leading singers’

or ‘bleeding singers’?

BD: [Wryly] Did you say ‘leading singers’

or ‘bleeding singers’?

BD:

Will they mean the death of opera in English?

BD:

Will they mean the death of opera in English? CSO Representative: Have you ever attended the Chicago

Opera Theater here?

CSO Representative: Have you ever attended the Chicago

Opera Theater here? BD:

It’s going to be a nightmare in the twenty-first century to go back through

the records and pull out who played in what group and when...

BD:

It’s going to be a nightmare in the twenty-first century to go back through

the records and pull out who played in what group and when... ME: [Thinks a moment] With operas that’s

not generally a problem. Funnily enough, the one person where it is

a problem is Wagner, because there are different publishers —

Peters, and Breitkkopf, or Schotts. So there are choices

to be made with Wagner sometimes. I am preparing my first Parsifal at the moment, which I’m going

to do in London in about fifteen months’ time, and I need to fix which score

I’m going to conduct from because the layout is very different, and that

affects the experience you have. What you see affects what you hear,

and it’s nice in operas not to have too many bars on one page. You

can begin to get the whole fabric of it — whole big

paragraphs, rather than just the little details.

ME: [Thinks a moment] With operas that’s

not generally a problem. Funnily enough, the one person where it is

a problem is Wagner, because there are different publishers —

Peters, and Breitkkopf, or Schotts. So there are choices

to be made with Wagner sometimes. I am preparing my first Parsifal at the moment, which I’m going

to do in London in about fifteen months’ time, and I need to fix which score

I’m going to conduct from because the layout is very different, and that

affects the experience you have. What you see affects what you hear,

and it’s nice in operas not to have too many bars on one page. You

can begin to get the whole fabric of it — whole big

paragraphs, rather than just the little details.  BD: So the audience on that one night will make

it a different performance than at Glyndebourne?

BD: So the audience on that one night will make

it a different performance than at Glyndebourne?

ME: [Again, he ponders the question] Don’t

be too impatient to push on and do things before you’re ready. Be

prepared to let things marinate inside you. Value that process!

We all realize, as the years go by, that more often than not, if it doesn’t

sound as we want it to sound then there’s something we can do without saying

anything to the orchestra to make it sound the way we want it. Part

of the job in rehearsals is finding the way to draw out the music from the

players by what we do. Consequently, the rehearsal process is very

much concerned, in my experience, with dividing up and helping the orchestra

to learn the piece, to get their fingers round it. But it is also necessary

to find the way to physicalize the inner life of the music, to drawn them

to play it expressively the way we want them to, and that demands an astonishingly

personal self-criticism which you don’t necessarily need to show that you’re

undergoing. So that it’s a balancing act, and all conducting is getting

the balance right.

ME: [Again, he ponders the question] Don’t

be too impatient to push on and do things before you’re ready. Be

prepared to let things marinate inside you. Value that process!

We all realize, as the years go by, that more often than not, if it doesn’t

sound as we want it to sound then there’s something we can do without saying

anything to the orchestra to make it sound the way we want it. Part

of the job in rehearsals is finding the way to draw out the music from the

players by what we do. Consequently, the rehearsal process is very

much concerned, in my experience, with dividing up and helping the orchestra

to learn the piece, to get their fingers round it. But it is also necessary

to find the way to physicalize the inner life of the music, to drawn them

to play it expressively the way we want them to, and that demands an astonishingly

personal self-criticism which you don’t necessarily need to show that you’re

undergoing. So that it’s a balancing act, and all conducting is getting

the balance right. ME:

Yes! Absolutely. They will feel the harshness that is very,

very powerful in the complete three-act version. It’s the job of an

opera company, surely, to present as wide a palate to the public as possible,

to keep everybody thinking about why we admire opera as much as we do, and

to keep the options open for people who are not sure that they will keep

trying. It is for those who might say after Traviata, “Well,

I didn’t quite like that thing I saw last time, about the lady who apparently

was supposed to be dying of consumption but she looked all right to me!”

[Both laugh] You hope to bring them back, and perhaps Peter Grimes will be the piece that they

would be completely overwhelmed by, and that will start them on a lifelong

enthusiasm to try different things.

ME:

Yes! Absolutely. They will feel the harshness that is very,

very powerful in the complete three-act version. It’s the job of an

opera company, surely, to present as wide a palate to the public as possible,

to keep everybody thinking about why we admire opera as much as we do, and

to keep the options open for people who are not sure that they will keep

trying. It is for those who might say after Traviata, “Well,

I didn’t quite like that thing I saw last time, about the lady who apparently

was supposed to be dying of consumption but she looked all right to me!”

[Both laugh] You hope to bring them back, and perhaps Peter Grimes will be the piece that they

would be completely overwhelmed by, and that will start them on a lifelong

enthusiasm to try different things. BD: It becomes a real collaboration?

BD: It becomes a real collaboration?

© 1986 & 1997 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on October 20, 1986 and October 10, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1997 and again in 2000; and on WNUR in 2003 and 2009. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.