NS: Yes. I did

have some studies, not at the

Conservatory, but private studies in Kiev. At

the St. Petersburg Conservatory I studied with my aunt, the famous

piano teacher Vengerova. Several years later I was a slavish

imitator of my ideals, which were Tchaikovsky,

Rimsky-Korsakov and Glière as a continuator of the

Russian school. I wrote songs and piano pieces all in

the same style. Then after my arrival in America I realized

that there was a different kind of music, and I began to invent

things — not just imitate Stravinsky or anybody;

in fact I never

imitated Stravinsky even though it was sort of de

rigueur. Everybody imitated Stravinsky. But

everybody was composing dissonances. Dissonant counterpoint was

the thing to do, but I invented something that I must say has a certain

element of originality, namely to compose music which is all

consonant vertically but set in different mutually exclusive

scales. Constant modulations create an

impression of dissonance, and yet not a single dissonance is present in

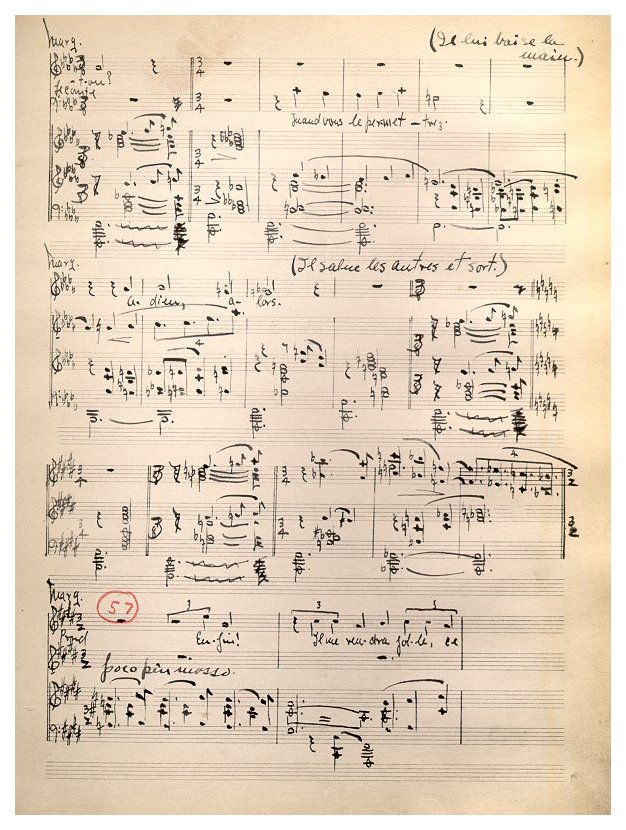

the actual musical texture. In this style I wrote a set of pieces

called

Studies in Black and White,

because the right hand played only on the

white keys and the left hand only on the black keys. It was

published in 1928 in the New Music

Quarterly,

a magazine which was started by my great friend Henry Cowell in San

Francisco. Amazingly enough it aroused considerable

interest among musicians, and I had some good reviews.

NS: Yes. I did

have some studies, not at the

Conservatory, but private studies in Kiev. At

the St. Petersburg Conservatory I studied with my aunt, the famous

piano teacher Vengerova. Several years later I was a slavish

imitator of my ideals, which were Tchaikovsky,

Rimsky-Korsakov and Glière as a continuator of the

Russian school. I wrote songs and piano pieces all in

the same style. Then after my arrival in America I realized

that there was a different kind of music, and I began to invent

things — not just imitate Stravinsky or anybody;

in fact I never

imitated Stravinsky even though it was sort of de

rigueur. Everybody imitated Stravinsky. But

everybody was composing dissonances. Dissonant counterpoint was

the thing to do, but I invented something that I must say has a certain

element of originality, namely to compose music which is all

consonant vertically but set in different mutually exclusive

scales. Constant modulations create an

impression of dissonance, and yet not a single dissonance is present in

the actual musical texture. In this style I wrote a set of pieces

called

Studies in Black and White,

because the right hand played only on the

white keys and the left hand only on the black keys. It was

published in 1928 in the New Music

Quarterly,

a magazine which was started by my great friend Henry Cowell in San

Francisco. Amazingly enough it aroused considerable

interest among musicians, and I had some good reviews.

BD:

He just lifted what he needed!

BD:

He just lifted what he needed!

NS: I don't believe that

this division exists

anymore. Stravinsky tried to break

this separation by writing for a jazz band in his Ebony Concerto. Even before

that,

Debussy used a cakewalk movement in his Children's Corner,

and Ravel used this sort of thing in his Sonata. In

fact he made several trips to Harlem to absorb this music. Then

Gershwin, as one of his biographers said, made

"an honest woman out of jazz." But Gershwin was a great composer

under any

circumstances.

NS: I don't believe that

this division exists

anymore. Stravinsky tried to break

this separation by writing for a jazz band in his Ebony Concerto. Even before

that,

Debussy used a cakewalk movement in his Children's Corner,

and Ravel used this sort of thing in his Sonata. In

fact he made several trips to Harlem to absorb this music. Then

Gershwin, as one of his biographers said, made

"an honest woman out of jazz." But Gershwin was a great composer

under any

circumstances. NS: Yes. I

published an article which you'll find in every biography of Mozart,

including Amadeus. Of

course Amadeus didn't

specify any blizzard, fortunately, but it showed Mozart being thrown

into a

common grave, which is also wrong. Mozart did have his

own grave, but his widow failed to pay dues! After eight

years, the rule was that all "stiffs" were removed into a common

grave. It was just the failure of Constanze Mozart to pay the

dues! I since found out that it would happen

to anyone, not only in Austria, but even in America!

NS: Yes. I

published an article which you'll find in every biography of Mozart,

including Amadeus. Of

course Amadeus didn't

specify any blizzard, fortunately, but it showed Mozart being thrown

into a

common grave, which is also wrong. Mozart did have his

own grave, but his widow failed to pay dues! After eight

years, the rule was that all "stiffs" were removed into a common

grave. It was just the failure of Constanze Mozart to pay the

dues! I since found out that it would happen

to anyone, not only in Austria, but even in America! NS: This

business of neo-Romanticism is something new! Composers like

Penderecki and others who wrote extremely

complex music, all of a sudden turn back and embrace tonality.

[See my Interview

with Krzysztof Penderecki.] In fact, Stravinsky did it in a

way because he returned to what he called

neoclassicism in the 1920s. So there is an obvious

movement away from all those complications, but still there are

numerous movements, mainly in electronic music, where anything

goes. In electronic music you don't even have to

specify, or try to adjust any kind of scale or anything. You can

divide the octave into 13 intervals. Krenek is

doing some very valuable work in electronic music, because he

is a real scholar of music, and so he didn't have to go back to

Romanticism or anything, but he used new resources. [See my Interview with Ernst

Krenek.]

NS: This

business of neo-Romanticism is something new! Composers like

Penderecki and others who wrote extremely

complex music, all of a sudden turn back and embrace tonality.

[See my Interview

with Krzysztof Penderecki.] In fact, Stravinsky did it in a

way because he returned to what he called

neoclassicism in the 1920s. So there is an obvious

movement away from all those complications, but still there are

numerous movements, mainly in electronic music, where anything

goes. In electronic music you don't even have to

specify, or try to adjust any kind of scale or anything. You can

divide the octave into 13 intervals. Krenek is

doing some very valuable work in electronic music, because he

is a real scholar of music, and so he didn't have to go back to

Romanticism or anything, but he used new resources. [See my Interview with Ernst

Krenek.] BD:

This is one of the joys of the Baker's

— going through and finding a composer whom you know

nothing about, reading about that composer and then finding

some recordings.

BD:

This is one of the joys of the Baker's

— going through and finding a composer whom you know

nothing about, reading about that composer and then finding

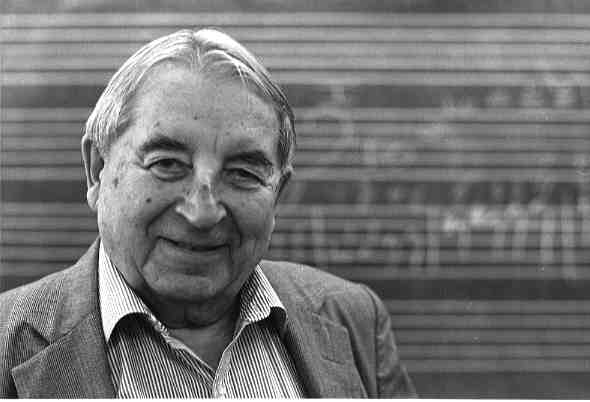

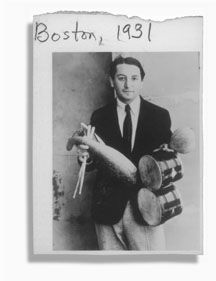

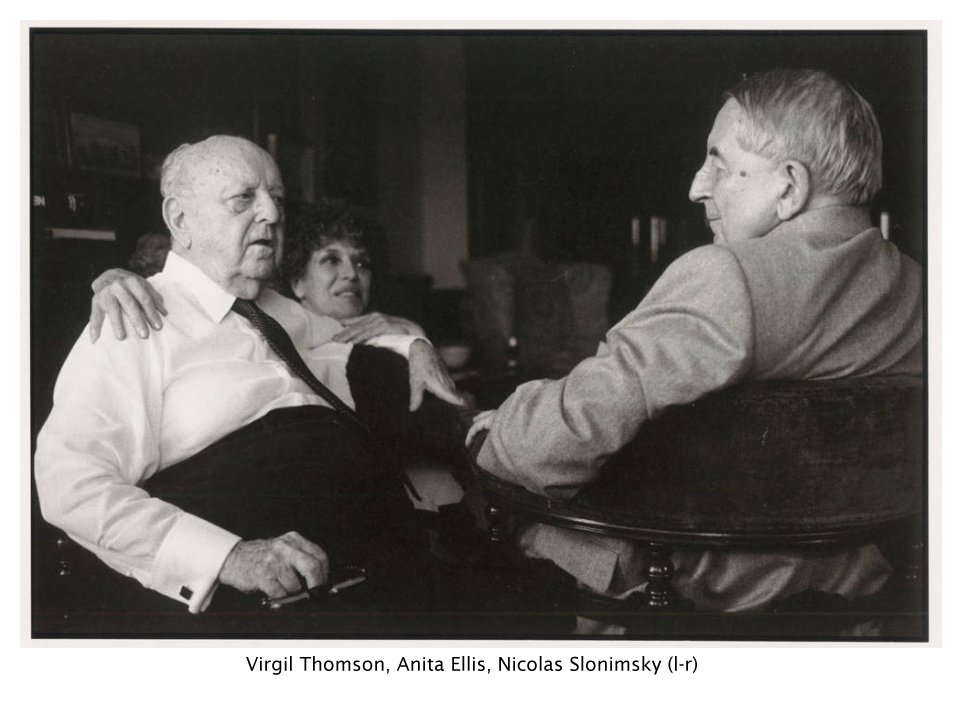

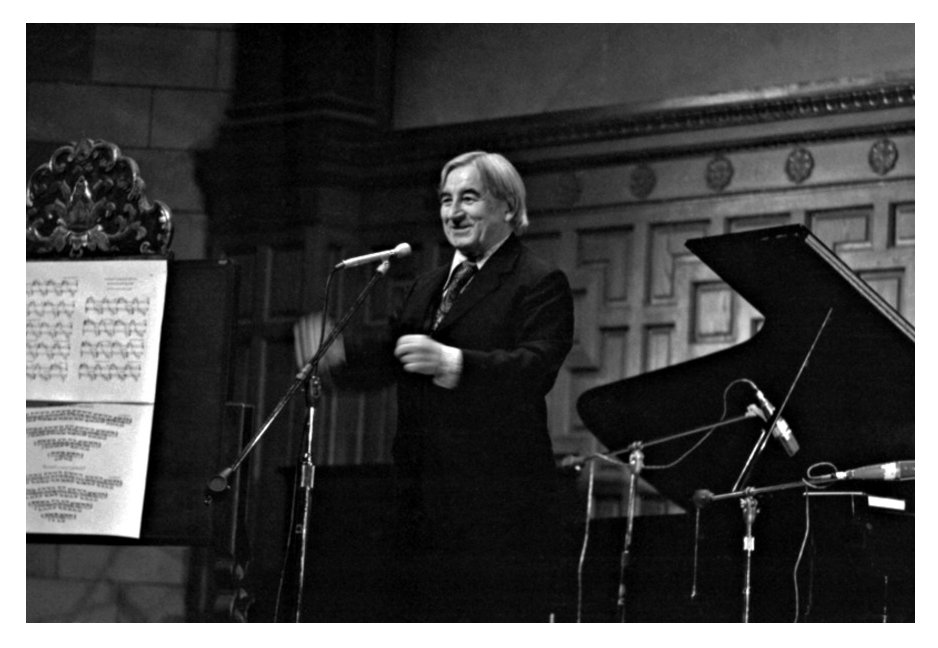

some recordings.| Nicolas Slonimsky, Conductor and

Lexicographer, Dies : Music: Russian-born scholar's knowledge and body

of work were legendary. He was 101. December 27, 1995, Los Angeles Times SHAWN HUBLER, TIMES STAFF WRITER Nicolas Slonimsky, the Russian-born composer and conductor who became one of the world's foremost musical lexicographers, died Monday at UCLA Medical Center. He was 101. Though not well-known outside the music world, the eccentric Slonimsky was a legend within it, renowned not only for his encyclopedic knowledge and prodigious body of work but also for his antic humor. Pierre Boulez was among his friends. [See my Interviews with Pierre Boulez. BD]. So was the late Frank Zappa. In fact, after Zappa sought him out in the early 1980s, Slonimsky performed one of his own compositions at a Zappa concert and enlisted the progressive rocker's daughter, Moon Zappa, to teach him Valley-speak. The musicologist and scholar later told reporters in his Russian-tinged accent that he had named one of his beloved cats Grody To The Max in her honor. Born in czarist St. Petersburg on April 27, 1894, Slonimsky came from a family of intellectuals. In the autobiography--which he had planned to title "Failed Wunderkind: A Rueful Autopsy" but was eventually released at his publisher's insistence as "Perfect Pitch"--he reported that his mother told him at age 6 that he was a genius. "This revelation came as no surprise to me," Slonimsky wrote. Possessed of perfect pitch, Slonimsky was first taught piano by his maternal aunt, but by age 10, he had begun to improvise. After graduating from St. Petersburg High School in 1912, he studied at the University of St. Petersburg and the St. Petersburg Conservatory of Music, where he learned music theory and composition from the same teachers who had mentored Shostakovich, Stravinsky and Prokofiev. By the 1920s, he was a touring concert pianist--a job that eventually landed him a post in the United States, where he was summoned in 1923 to coach opera at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y. Able to speak only four words of English--"yes," "thank you," and "please"--he gradually taught himself the language by studying the librettos of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas and the ads in the Saturday Evening Post. Two years later, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra heard Slonimsky at Rochester and invited him to move to Boston as his secretary and companion. There, he published two collections of songs, conducted the Harvard University orchestra and organized the Chamber Orchestra of Boston. In 1928, he composed the song, "My Little Pool," which has only 12 bars and calls for only black keys in the left hand and white keys in the right. It was during this period that he also met and married the former Dorothy Adlow, an art critic and lecturer. By the 1930s, he was an ardent champion of 20th-century music, conducting, for example, the piano concerto of Bela Bartók with the composer as soloist and the Berlin Philharmonic in programs of modern American music. But his penchant for presenting new music doomed his conducting career. In 1933, after conducting the L.A. Philharmonic to considerable acclaim, he was engaged to conduct the philharmonic's summer season at the Hollywood Bowl. Insisting on the importance of exposing contemporary audiences to contemporary music, he tried to force-feed modern music to the staid Los Angeles audience with disastrous results. The orchestra mutinied, the trustees intervened and, as Slonimsky later put it, he was "given the bum's rush out of Hollywood." His conducting career suddenly began to break up. But Slonimsky, by now a parent, embarked on a second career,

turning from the music itself to scholarly research and documentation.

His "Music Since 1900," comprising a chronology of almost 2,000 musical

events and biographies, was published in 1937, and characterized as a

landmark of American musical scholarship. |

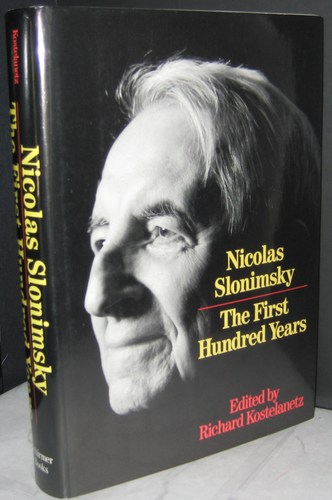

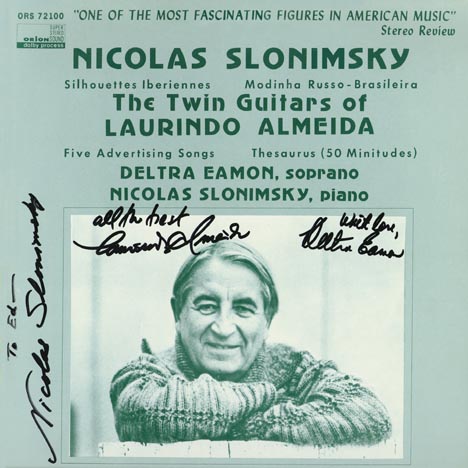

| Nicolas Slonimsky, Author of

Widely Used Reference Works on Music, Dies at 101 By ALLAN KOZINN, New York Times Published: December 27, 1995 Nicolas Slonimsky, a formidably gifted musicologist and lexicographer who also made his mark as a conductor, pianist and composer, died on Monday at the U.C.L.A. Medical Center in Los Angeles. He was 101. Mr. Slonimsky's many reference works, among them "Music Since 1900," "A Lexicon of Musical Invective" and the last several editions of Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, are considered indispensable by musicians, critics and music lovers. A compendium drawn from his writings, "Nicolas Slonimsky: The First Hundred Years," edited by Richard Kostelanetz, was published last year. Mr. Slonimsky was no mere purveyor of facts. He challenged accepted lore and debunked myths that had found their way into biographies and reference works. Rather than repeat the Romantic depiction of a blizzard at Mozart's funeral, he consulted Austrian weather bureaus and discovered that the story was untrue. He was also fascinated by unusual details. Readers in search of basic information might in the process learn, for example, that Stravinsky had a toothache the day he completed "Le Sacre du Printemps," or that Schoenberg and Rossini had triskaidekaphobia, an irrational fear of the number 13. He enlivened his dictionary entries with astute, witty and sometimes waspish observations, and in the later editions of Baker, he introduced some musicians with lavish evaluations. Where The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians soberly describes Mozart, for example, as "one of the composers who brought the Viennese Classical style to its height," Mr. Slonimsky's identifying sentence reads: "Supreme Austrian genius of music whose works in every genre are unsurpassed in lyric beauty, rhythmic variety and effortless melodic invention." Mr. Slonimsky's entertaining style was reflected in his other activities. A favorite party trick -- one he performed at an Alice Tully Hall tribute to him in 1987 and also on the "Tonight Show" -- was to play the melody line of the Chopin "Black Key" Etude by rolling an orange across the keys. Seemingly open to musical experiences of all kinds, he performed some of his own music at a Frank Zappa concert in Santa Monica, Calif., in 1981 and maintained a friendship with the iconoclastic rock composer. He named his cat Grody-to-the-Max, after learning the expression from Zappa's daughter, Moon Unit. But he had a thoroughly serious side as well. He was a vigorous champion of new music all his life. In the 1920's he founded the Chamber Orchestra of Boston, and he gave premieres of Ives's "Three Places in New England" in 1931 and Varese's "Ionisation" in 1933. (Varese dedicated the work to him.) He also championed Henry Cowell and Carlos Chavez, and conducted Bartók's First Piano Concerto with the composer as soloist. He later said his conducting career had foundered because of his insistence on programming new music. Nicolas Slonimsky was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, on April 27, 1894. In his autobiographical entry in Baker, he wrote: "Possessed by inordinate ambition, aggravated by the endemic intellectuality of his family of both maternal and paternal branches (novelists, revolutionary poets, literary critics, mathematicians, inventors of useless artificial languages, Hebrew scholars, speculative philosophers), he became determined to excel beyond common decency in all these doctrines." He excelled in several of them, but music -- though absent from the list of family achievements -- was his primary interest from the age of 6, when he began studying piano with Isabelle Vengerova, his aunt (and later a teacher of Samuel Barber and Leonard Bernstein). He studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory until 1914. He was drafted into the Russian Army just before the revolution. In 1918 he began touring as a vocal accompanist, then worked his way through Turkey and Bulgaria as a pianist in theaters and silent movie houses, arriving in Paris in 1921. There he became a rehearsal pianist for the conductor Serge Koussevitzky. He came to the United States in 1923 to work as an accompanist in the newly created opera department at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, where he continued his composition and conducting studies. After two years there, he moved to Boston to resume his position as Koussevitzky's assistant. He also taught music theory at the Boston Conservatory and the Malkin Conservatory, and he began to contribute articles on music to The Boston Evening Transcript, The Christian Science Monitor and Etude magazine. In 1927, he started his Chamber Orchestra of Boston and began to solicit music from composers he admired. Ives, thrilled with Mr. Slonimsky's performance of "Three Places," sponsored a European tour that allowed Mr. Slonimsky to present recent American works. In Paris, during that 1931 tour, he married Dorothy Adlow, an art critic for The Christian Science Monitor. Mr. Slonimsky became an American citizen the same year. His conducting career flourished briefly, but by the mid-1940's he had returned to academia. He headed the Slavonic languages and literature department at Harvard from 1945 to 1947, and toured Europe and the Middle East as a lecturer for the State Department. After his wife died in 1964, he moved to Los Angeles and taught for three years at the University of California. His first book, "Music Since 1900," appeared in 1937. A day-by-day chronology of important as well as amusing but trivial events in 20th-century music, the work has been revised several times, most recently in 1987. In his Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (1947), he ingeniously catalogued combinations of notes that could be used as musical themes. Jazz musicians found the book particularly useful; John Coltrane reportedly required his band members to play through it. Mr. Slonimsky edited the Thompson's International Cyclopedia of Music and Musicians from 1946 to 1958 and in 1958 became editor of the Baker, beginning with the fifth edition. He completely revamped the book for the sixth edition, published in 1978, and oversaw two more editions as well as abridged versions. Taking a break from biography, he turned his attention to musical terms in his Lectionary of Music (1989). His books also include the "Lexicon of Musical Invective" (1953), a collection of scathing reviews of musical masterpieces; "Music of Latin America" (1945), "The Road to Music" (1947) and "A Thing or Two About Music" (1948). His autobiography (which he wanted to call "Failed Wunderkind") was published as "Perfect Pitch" in 1988. As a composer, Mr. Slonimsky wrote (in his own Baker entry) that he "cultivated miniature forms, usually with a gimmick." These include a set of "Advertising Songs" (settings of advertising copy that had appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, 1925); "Gravestones at Hancock" (settings of epitaphs, 1945); "Studies in Black and White" (a piano work in which one hand played black keys, the other white keys, 1928), "My Toy Balloon" (which he described as his "only decent orchestral work," 1945) and "51 Minitudes for Piano" (1972-76). He is survived by a daughter, Electra Yourke of Manhattan, and two grandchildren. |

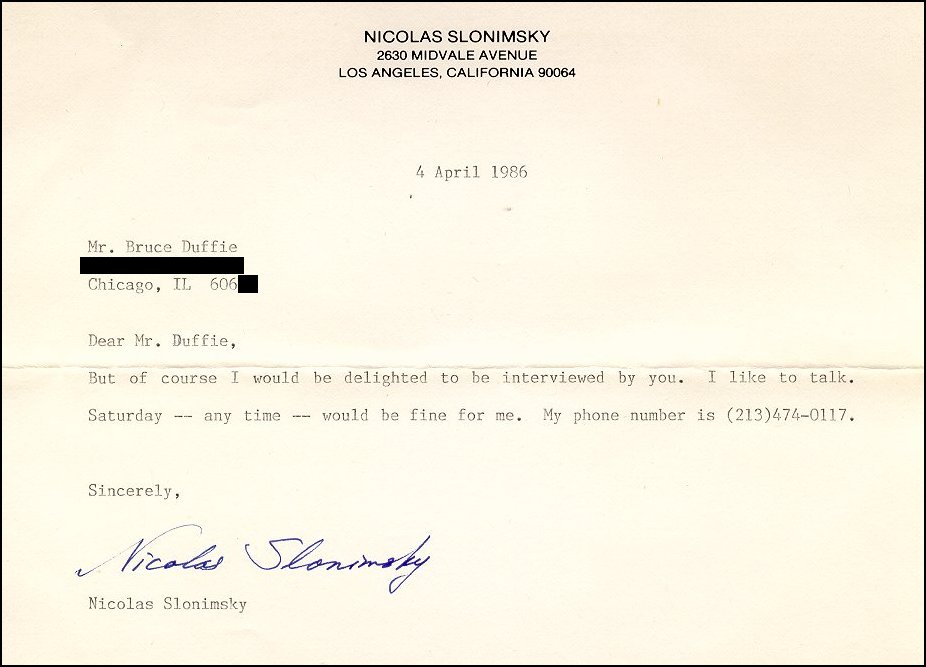

This interview was recorded on the telephone on April 12, 1986. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1989, 1994 and again in 1999. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.