JC: The same people that I’ve always had in mind.

I do not write primarily for a connoisseur crowd. I have never aimed

my stuff primarily at college people

— faculty or students. I’ve always

tried to write for the general public, and have basically the same kind of

intention that Arthur Honegger did. I know my music probably does not

sound anything like Honegger’s, but I sympathize with what he was trying

to do, particularly in his orchestral works, in the tone poems, not just

in things that were very graphic in their portrayals like Pacific 231, or even like the Summer Pastorale and the Hymn of Joy. I’ve always had the

idea that music should not just be rational or logical. I’ve always

had the French ideal of clarity, that you should be able to listen to the

music and have a general idea, through its transparency, of how it is put

together. I don’t believe in hocus pocus and throwing dust in people’s

eyes. I would rather that it all be there, clear and transparent.

I think that everything should come basically out of the human voice, and

that’s why I’ve always tended to write in a melodic, rather than in a percussive

way. That’s why I don’t have bloops and bleeps with long periods of

silence in between, because I believe that that cuts off communication.

I think that music should be communication, and that it should communicate

not just sounds, but feelings. So I’m writing, primarily I think, for

people that listen to music for reasons connected with emotions. I

hope that people will have some kind of a reaction which is not just intellectual,

but emotional, too.

JC: The same people that I’ve always had in mind.

I do not write primarily for a connoisseur crowd. I have never aimed

my stuff primarily at college people

— faculty or students. I’ve always

tried to write for the general public, and have basically the same kind of

intention that Arthur Honegger did. I know my music probably does not

sound anything like Honegger’s, but I sympathize with what he was trying

to do, particularly in his orchestral works, in the tone poems, not just

in things that were very graphic in their portrayals like Pacific 231, or even like the Summer Pastorale and the Hymn of Joy. I’ve always had the

idea that music should not just be rational or logical. I’ve always

had the French ideal of clarity, that you should be able to listen to the

music and have a general idea, through its transparency, of how it is put

together. I don’t believe in hocus pocus and throwing dust in people’s

eyes. I would rather that it all be there, clear and transparent.

I think that everything should come basically out of the human voice, and

that’s why I’ve always tended to write in a melodic, rather than in a percussive

way. That’s why I don’t have bloops and bleeps with long periods of

silence in between, because I believe that that cuts off communication.

I think that music should be communication, and that it should communicate

not just sounds, but feelings. So I’m writing, primarily I think, for

people that listen to music for reasons connected with emotions. I

hope that people will have some kind of a reaction which is not just intellectual,

but emotional, too. JC: I’m just giving you how the parameters of how

the thing was set up. One parameter was to feature violin and piano,

and the next one was to use as many of the available performers as possible.

The third parameter was that since this had something to do with the treaty

between Holland and the United States, it would be nice if I could perhaps

incorporate into the piece some authentic melodies that were used by the

Dutch settlers in the New World. It was a challenge, but I did it,

and it gave me a lot of fun. I made my living for many years as the

musicologist at ASCAP, so spent a lot of time at the Lincoln Center Library

reading various things, mostly in Dutch, and locating authentic materials.

The Dutch musicologists have done a magnificent job in that, so thanks to

their work it was very easy for me to find what I wanted, which were folk

tunes like O Sacred Head, Now Wounded.

There were things that had originally been used for secular purposes, like

drinking songs, that had wound up in slowed-down versions and with new lyrics,

used as chorales by the Dutch Protestant Church. Some of these showed

both the religious and earlier forms of these tunes. I used the earlier

in the finale of my work, so the last movement is a fantasia on two Dutch

tunes which were probably known to the settlers in the New World. These

were tavern songs and peasant things; I did not use Dutch art music because

there were very few of these people in the New Netherlands. The tunes

were mostly utilized for agricultural or money-making purposes. The

fact that the Library of Congress had a woodwind quintet available plus the

violinist and pianist made me decide to make a sort of a concerto grosso

out of the work. There are sections where it’s just the violin and piano

working together, sometimes the wind quintet works by itself, and sometimes

all of them together. It’s a three movement work; the first two movements

are all my own material, and the third is based on those two old melodies.

The first one is known to most Dutch people as Die Burg op Zoom, and those words were

added by a Dutch historian. As a mnemonic device, he used popular melodies

of his day as a memory aide for people to memorize his words which were about

various things like important battles of the Dutch against the Spaniards,

and so forth. So this was about the siege of Burg op Zoom, a town in

Holland, the advancing Spanish armies, and how the Dutch managed to fight

them off so that the town never was taken. The other melody, which

wound up in Psalms, in a very doleful setting about how glory has departed

and they have been plundered; the godless have taken over everything, and

our temple lays disgraced — you know, one of these real downers! The

original words were something like “Oh, merry month of May! Everything

is green and beautiful and the birds are singing all night and all day, and

I am going to the tavern and have something wonderful to drink and to toast

my sweetheart,” and so forth! [Both laugh]

JC: I’m just giving you how the parameters of how

the thing was set up. One parameter was to feature violin and piano,

and the next one was to use as many of the available performers as possible.

The third parameter was that since this had something to do with the treaty

between Holland and the United States, it would be nice if I could perhaps

incorporate into the piece some authentic melodies that were used by the

Dutch settlers in the New World. It was a challenge, but I did it,

and it gave me a lot of fun. I made my living for many years as the

musicologist at ASCAP, so spent a lot of time at the Lincoln Center Library

reading various things, mostly in Dutch, and locating authentic materials.

The Dutch musicologists have done a magnificent job in that, so thanks to

their work it was very easy for me to find what I wanted, which were folk

tunes like O Sacred Head, Now Wounded.

There were things that had originally been used for secular purposes, like

drinking songs, that had wound up in slowed-down versions and with new lyrics,

used as chorales by the Dutch Protestant Church. Some of these showed

both the religious and earlier forms of these tunes. I used the earlier

in the finale of my work, so the last movement is a fantasia on two Dutch

tunes which were probably known to the settlers in the New World. These

were tavern songs and peasant things; I did not use Dutch art music because

there were very few of these people in the New Netherlands. The tunes

were mostly utilized for agricultural or money-making purposes. The

fact that the Library of Congress had a woodwind quintet available plus the

violinist and pianist made me decide to make a sort of a concerto grosso

out of the work. There are sections where it’s just the violin and piano

working together, sometimes the wind quintet works by itself, and sometimes

all of them together. It’s a three movement work; the first two movements

are all my own material, and the third is based on those two old melodies.

The first one is known to most Dutch people as Die Burg op Zoom, and those words were

added by a Dutch historian. As a mnemonic device, he used popular melodies

of his day as a memory aide for people to memorize his words which were about

various things like important battles of the Dutch against the Spaniards,

and so forth. So this was about the siege of Burg op Zoom, a town in

Holland, the advancing Spanish armies, and how the Dutch managed to fight

them off so that the town never was taken. The other melody, which

wound up in Psalms, in a very doleful setting about how glory has departed

and they have been plundered; the godless have taken over everything, and

our temple lays disgraced — you know, one of these real downers! The

original words were something like “Oh, merry month of May! Everything

is green and beautiful and the birds are singing all night and all day, and

I am going to the tavern and have something wonderful to drink and to toast

my sweetheart,” and so forth! [Both laugh] JC: Music is like any other thing. It can

be used for so many different reasons. It’s up to the user to decide

what it should be used for. A person who supplies beer, let’s say,

once the beer has left the supermarket, the seller has no control anymore

over what happens to the beer. It will reach somebody’s home.

That person may drink only one can of beer per night, or maybe only one can

per week, or he may elect to down an entire six-pack all in one sitting.

That’s his privilege. Whether it’s good or bad judgment to do something

is up to the users. It’s that way with art, also. You can abuse

art by using it in such a way as to hurt yourself. Don Quixote did,

reading all of these historical romances! He read so many of them in

such fast succession that he went bonkers and turned into the kind of character

that people refer to today as “quixotic,”

not really of this world, doing things that to the rest of the world seem

ridiculous or irrational. Most creative people in this particular time

and place are doing their artistic thing as a labor of love. They don’t

really expect that they can make a living from it, but they go on doing it

anyway because each of them feels a calling; he feels there is something

where he must do this. It will not let him go. For a creative

person, when something calls, you really cannot tell it to go away.

When I wrote that opera, I was in the grip of something that I was unable

to shake off until I sat down and took out pencil and paper and dealt with

it.

JC: Music is like any other thing. It can

be used for so many different reasons. It’s up to the user to decide

what it should be used for. A person who supplies beer, let’s say,

once the beer has left the supermarket, the seller has no control anymore

over what happens to the beer. It will reach somebody’s home.

That person may drink only one can of beer per night, or maybe only one can

per week, or he may elect to down an entire six-pack all in one sitting.

That’s his privilege. Whether it’s good or bad judgment to do something

is up to the users. It’s that way with art, also. You can abuse

art by using it in such a way as to hurt yourself. Don Quixote did,

reading all of these historical romances! He read so many of them in

such fast succession that he went bonkers and turned into the kind of character

that people refer to today as “quixotic,”

not really of this world, doing things that to the rest of the world seem

ridiculous or irrational. Most creative people in this particular time

and place are doing their artistic thing as a labor of love. They don’t

really expect that they can make a living from it, but they go on doing it

anyway because each of them feels a calling; he feels there is something

where he must do this. It will not let him go. For a creative

person, when something calls, you really cannot tell it to go away.

When I wrote that opera, I was in the grip of something that I was unable

to shake off until I sat down and took out pencil and paper and dealt with

it. BD: I’m an old bassoon player, so I listened to

that first and it was a lot of fun.

BD: I’m an old bassoon player, so I listened to

that first and it was a lot of fun. JC: Yes, I am, because from what I’ve seen after

all of these years, I believe that there is always going to be someone who

will feel that it’s important to write for people in general, and not just

for the elect or for whoever is up there on a pedestal. In the old

days, there were composers who wrote only for the church or only for the

nobility, and since that was the only patron or customer out there, they

didn’t really bother to think very much about the other people. But

we’re in a different era now, and one has to consider the other people that

are out there. I also think that there’s a question of altruism.

Every composer should ask himself at one point or another, “Who

am I writing for? Am I writing just for myself? Am I not writing

for other people as well as for myself? The world gave me things.

I have been eating and drinking all of these years because of the bounty of

the earth, or of my fellow men. What am I giving back to them?

Is it enough just to accept a weekly paycheck and not give anything more?”

It’s like people who have been asked to give to some worthy charity, and

they say, “Why pick on me? I earn my living. I’ve already paid

my dues.” There is a philosophical question in there, whether you use

such a phrase or not. I think it’s important. Unless you are sacrificing

yourself, which I don’t think anybody should willingly do, I think that people

should try to leave the earth having given back maybe a little bit more than

they took.

JC: Yes, I am, because from what I’ve seen after

all of these years, I believe that there is always going to be someone who

will feel that it’s important to write for people in general, and not just

for the elect or for whoever is up there on a pedestal. In the old

days, there were composers who wrote only for the church or only for the

nobility, and since that was the only patron or customer out there, they

didn’t really bother to think very much about the other people. But

we’re in a different era now, and one has to consider the other people that

are out there. I also think that there’s a question of altruism.

Every composer should ask himself at one point or another, “Who

am I writing for? Am I writing just for myself? Am I not writing

for other people as well as for myself? The world gave me things.

I have been eating and drinking all of these years because of the bounty of

the earth, or of my fellow men. What am I giving back to them?

Is it enough just to accept a weekly paycheck and not give anything more?”

It’s like people who have been asked to give to some worthy charity, and

they say, “Why pick on me? I earn my living. I’ve already paid

my dues.” There is a philosophical question in there, whether you use

such a phrase or not. I think it’s important. Unless you are sacrificing

yourself, which I don’t think anybody should willingly do, I think that people

should try to leave the earth having given back maybe a little bit more than

they took. JC: That is the most difficult question for any composer.

The important thing about writing a piece of music is to know, or to realize,

not what to include, but what to leave out. You have to be willing

to cut mercilessly. It doesn’t matter whether you’re writing words

or music, or what the situation is. It’s better to be too short than

too long. It’s better to be Franz Berwald than Gustav Mahler.

JC: That is the most difficult question for any composer.

The important thing about writing a piece of music is to know, or to realize,

not what to include, but what to leave out. You have to be willing

to cut mercilessly. It doesn’t matter whether you’re writing words

or music, or what the situation is. It’s better to be too short than

too long. It’s better to be Franz Berwald than Gustav Mahler. Various commissions since the time of the interview...

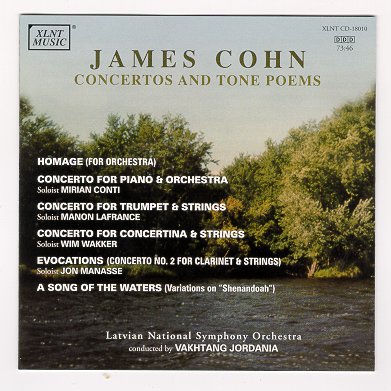

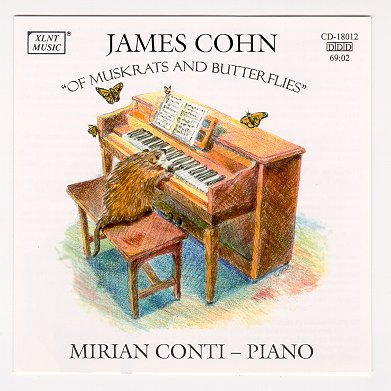

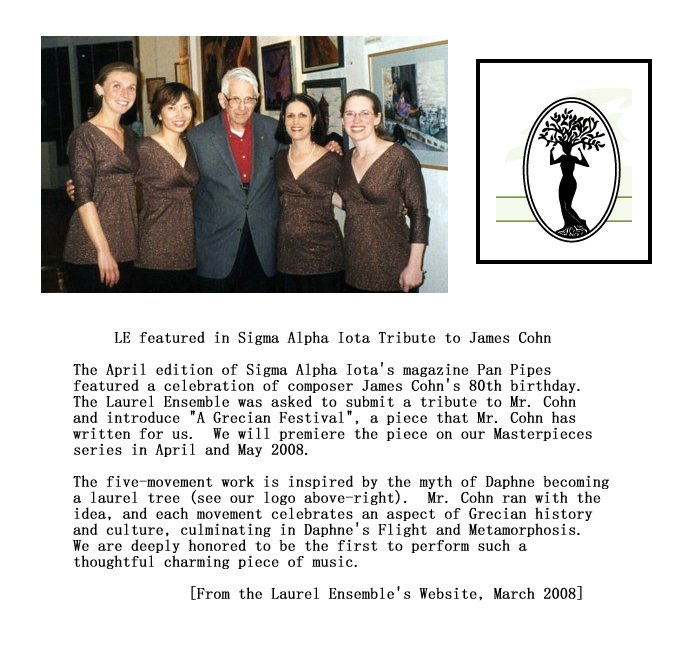

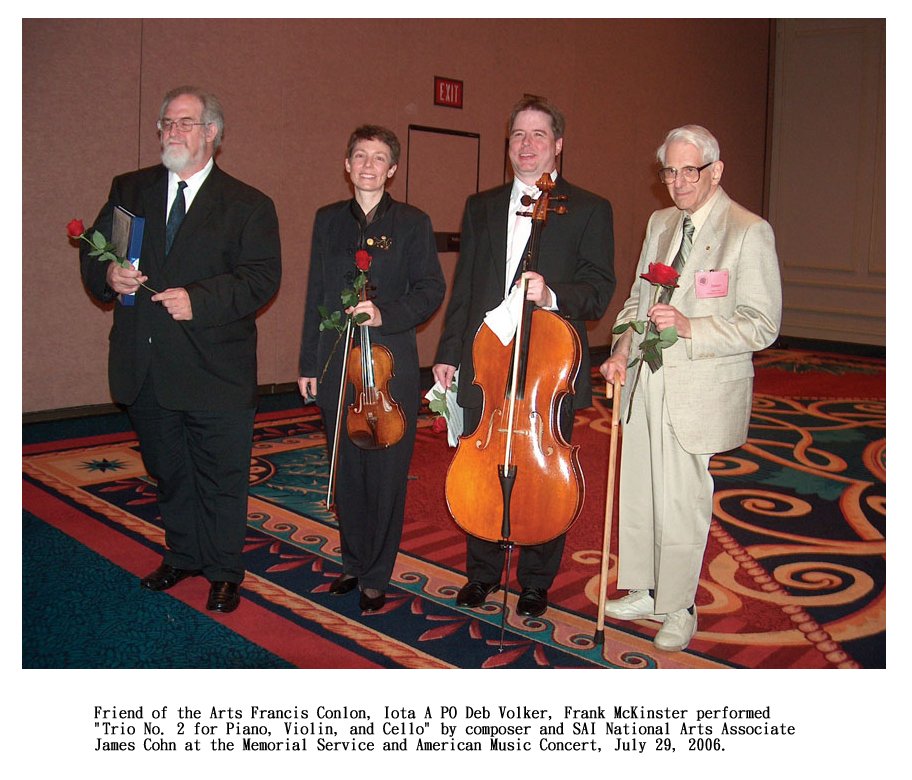

Various commissions since the time of the interview...Piano Concerto, commissioned by the Argentine pianist Mirian Conti; Violin Concerto, commissioned and performed by the American violinist Eric Grossman; Trumpet Concerto, commissioned by trumpeter Jeffrey Silberschlag; Clarinet Concerto #1; Evocations (Clarinet Concerto #2); these and other works for clarinet commissioned and performed by John Manasse; [It was the first Clarinet Concerto which precipitated Jim's visit to Ostend Belgium where he wrote Caprice for the Claribel Clarinet Choir in Ostend in 1997, which was the foundation for a great friendship between Maestro Guido Six, which resulted in the commission in February of 2010 for Texas Suite for future performance at the TMEA in San Antonio]; A Grecian Festival for the Laurel Ensemble, based in California [see photo below]; Trio No. 2 for Piano, Violin and Cello, commissioned by Sigma Alpha Iota and given its world premiere at Sigma Alpha Iota’s Convention [see photo below in next box]; Three Dances for Clarinet and Guitar, commissioned by Raphael Sanders and David Galvez; Mozart Fantasy, Fiesta Latina and Dance of Praise, commissioned by the Quintet of the Americas; The Empty Platter (from a poem by Ogden Nash) and Three Bon-Bons for the New York Treble Singers;

Fantasy

on Two Asian Folk Songs for Flute/Oboe and

Orchestra for

Jeffrey Liang & the Chinese Youth Orchestra; Sonata for Violin & Piano,

commissioned by Kees Kooper, the

renowned Dutch Violinist.

|

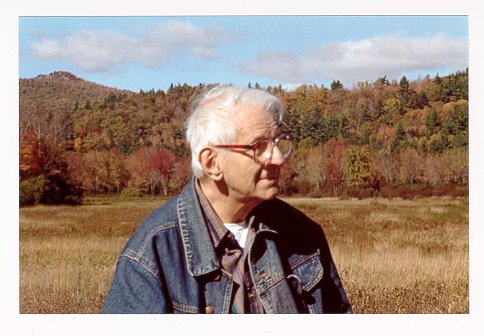

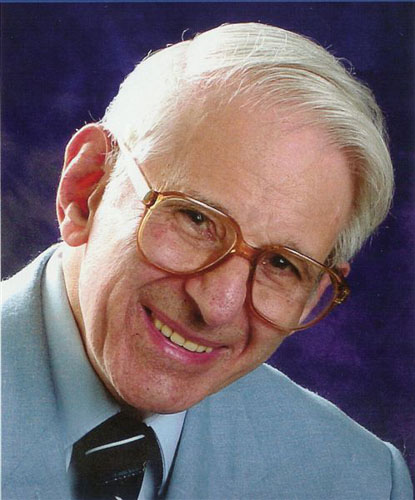

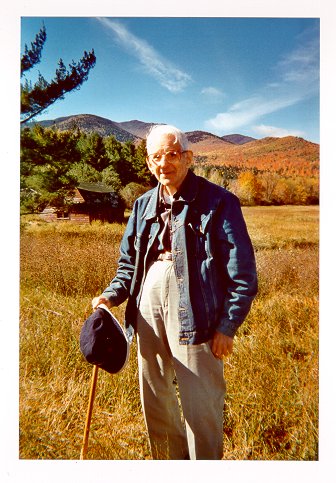

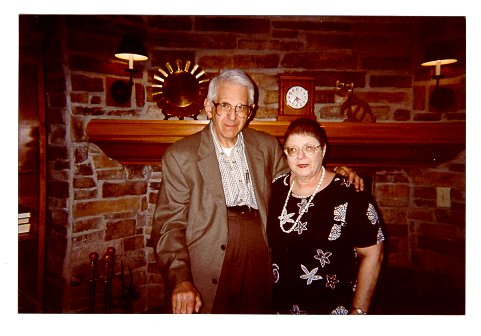

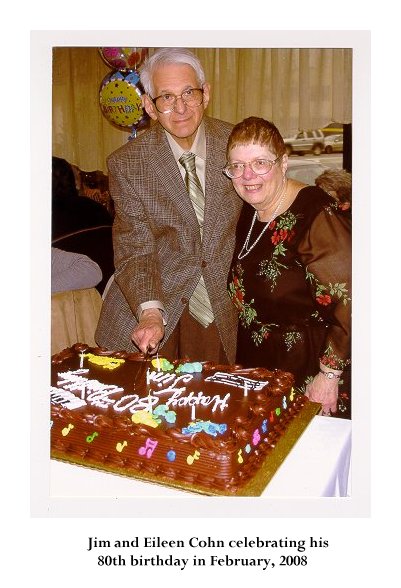

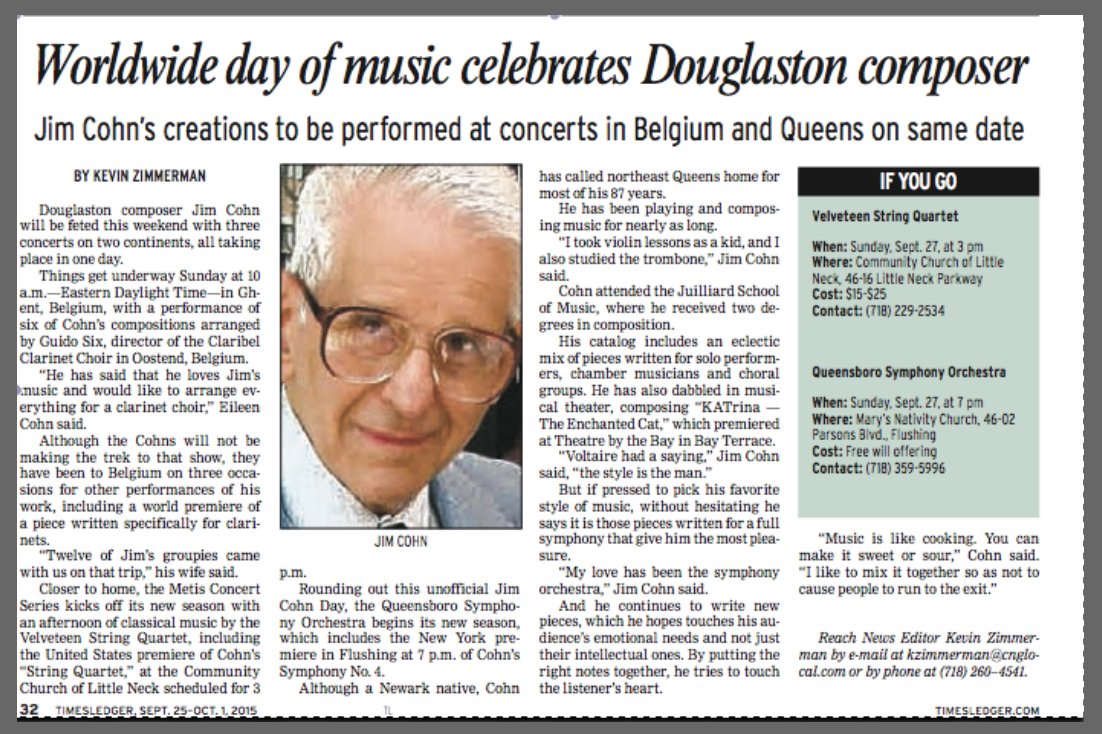

| JAMES

COHN was born in 1928 in Newark, New Jersey, and took violin and piano

lessons there. Later he studied composition with Roy Harris, Wayne Barlow

and Bernard Wagenaar, and majored in Composition at Juilliard, graduating

in 1950. He is married, and has lived and worked for many years in New York

City. He was initiated as a National Arts Associate of Sigma Alpha Iota (International

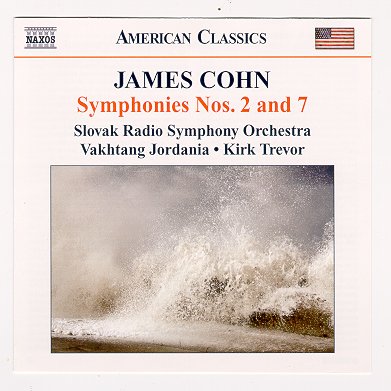

Music Fraternity) (SAI) in the Tulsa Oklahoma chapter in 1998. He has written solo, chamber, choral and orchestral works, and his catalog includes 3 string quartets, 5 piano sonatas and 8 symphonies. Some have won awards, including a Queen Elisabeth of Belgium Prize for his Symphony No. 2 (premiered at Brussels) and an A.I.D.E.M. prize for his Symphony No. 4 (premiered in Florence at the Maggio Musicale). Paul Paray and the Detroit Symphony introduced the composer's Symphony No. 3 and Variations on "The Wayfaring Stranger", and his opera The Fall of the City received its premiere in Athens, Ohio after winning the Ohio University Opera Award. He has had many performances of his choral and chamber music, and world-wide use of his music commissioned for television and cinema. His most recent completed orchestral work is a Piano Concerto, commissioned by the Argentine pianist Mirian Conti, and his most recent chamber music work is the Trio No. 2 for Piano, Violin and Cello, commissioned by Sigma Alpha Iota and scheduled for premiere at Sigma Alpha Iota's annual Convention in the summer of 2006 at Orlando, Florida, [photo below] 3 Dances for Clarinet and Guitar, commissioned by Raphael Sanders and David Galvez and Duo for Clarinet & Violin, commissioned by Julianne Kirk and Adda Kridler.

Commissions for other works have come from The McKim Fund in the Library of Congress (for the Concerto da camera for Violin, Piano and Wind Quintet), Pennsylvania's "Music At Gretna" festival (for the Mount Gretna Suite, for chamber orchestra), Jon Manasse (for the Concerto No. 1 for Clarinet and Strings), Christopher Jepperson (for 3 Evocations [Clarinet Concerto No. 2]), Jeffrey Silberschlag (for the Concerto for Trumpet and Strings) and Claribel (the Belgian 30-piece clarinet ensemble) (for the 3-movement suite Caprice). SOME WORDS FROM THE PRESS

"The highlight of the program was the first performance of three (choral) works by James Cohn, to texts by Ogden Nash. They proved to be indescribably funny, the poet's shrewdly nonsensical verses being set in a mock-heroic manner worthy of Sir Arthur Sullivan. The works, moreover, were effective in performance. Mr. Cohn has technical skill, an inventive musical imagination, a flair for setting text to music and a sense of humor. All these qualities are as rare as they are admirable, and it is hoped that Mr. Cohn will soon be heard from again." - THE NEW YORK TIMES "Mr. Cohn's opus (Variations on "The Wayfaring Stranger", premiered by Paul Paray and the Detroit Symphony) proved to be spectacularly appealing. Moreover it is melodic... The Variations run the gamut of human emotions with delightful solo lines... It was a superb performance of a superb work." - THE WINDSOR (ONT.) STAR "Cohn's Symphony (No. 3) is an eminently attractive one which makes its claim on the attention with the opening phrases and sustains the interest throughout the performance. There is an economy of means in the orchestration of the piece, but no yielding of inventiveness or imaginative composition. Indeed, the work throughout is marked strongly by individuality, and comes as a refreshing experience in modern music." - DETROIT FREE PRESS "I am an unabashed fan of the music of James Cohn... Thus I was excited by the prospect of a new clarinet concerto (No. 1)... and I was not disappointed. The piece is easily in a class with (Gerald) Finzi's concerto; it is melodic and charming, without sounding old-fashioned or stuffy... Cohn seems not to mind writing music that one can enjoy, and I applaud him for it." - AMERICAN RECORD GUIDE "Imagine: here is contemporary music that is easy to listen to and enjoyable... Cohn reminds me of (Jean) Francaix in his expert writing for wind instruments and for his infectious good humor and high spirits, and of Hindemith for his angular melodies. These comparisons are not meant to suggest that Cohn is not original, for he is... I would rank the Wind Quintet high on the long list of such works in the literature." - AMERICAN RECORD GUIDE "James Cohn's music is light and gay yet thoroughly classical; the wind music has something of the spirit of Parisian wind pieces, but with a distinctly American flavor. Chief characteristics are brevity, wit and clarity; Cohn's melodies are charming." - FANFARE "Witty and well-crafted music. Cohn's orchestral music is well structured, warmly tonal and rich in grace and wit" - GRAMOPHONE "The six works on this disk are high on charm and craftsmanship." - CLASSICS TODAY |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on October 19, 1987.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1991, 1993 and 1998,

and on WNUR in 2006 and 2008. This transcription was made and posted

on this website in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.