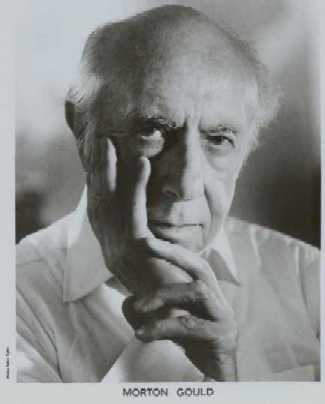

Presenting MORTON GOULD

A Conversation With Bruce Duffie

Presenting MORTON GOULD

A Conversation With Bruce Duffie

Among the small group of truly remarkable musicians in the world, very few have been successful at as many different endeavors as Morton Gould. In both the popular fields and the more serious fields, he has given the world his own original material, presented others' works as conductor and pianist, and been an advocate for creators in all areas.

Two biographies are reproduced at the end of this interview where one may

see the range of his accomplishment. Needless to say, this was a major

talent which was used to its fullest in a long and productive life, and we

all owe him a tremendous debt. On a personal note, it was Gould who

presented to me the ASCAP/Deems Taylor Broadcast Award in 1991, at a ceremony

in New York City. It remains one of the most special moments of my

life.

[For another photo of us, and an image of the award, click here .]

Besides meeting him at that reception, it was my pleasure to interview

Morton Gould on a couple of occasions. This, the second of our recorded

chats, was held in Chicago in June of 1988, shortly before his 75th birthday.

It was a very busy time for him, and I was very pleased when he agreed to

spend a few minutes with me. Here is what was said that afternoon .

. . . .

Bruce Duffie: Let's start right there. Do you get enough time to compose?

Morton Gould: Right now, of course, along with my involvement as a composer/conductor, I'm also President of ASCAP, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. This is the beginning of my third year. I was just re-elected by the Board, and it's a working Presidency, so it takes a lot of time. I've had to cut back on some of my own personal and professional activities, but now I'm trying to re-shape my schedule so I have more time to write. To compose, you know, is like breathing to me, so I need that. And this is me. But I've always had a career that has not been simple. I've always been involved in more than just composing. I've been a conductor, a recording artist, I've served on many artistic committees, and been, what I call, a musical citizen.

BD: Has this, in any way, helped your composing - to be out among the people who are doing it and receiving it?

MG: No, I don't think so, because one is played as a composer. If you write something that is durable, it has to be durable beyond the fact that you might have other kinds of public recognition. It might help in certain circumstances, but basically, the music has to have its own kind of staying power.

BD: What makes a piece of music 'durable'?

MG: I wish we knew because then all of us could write every

piece to be durable. It doesn't always come out that way. You

write a number of works and if you're lucky, a few of them are durable.

And even that's a relative term. It could last ten years, twenty years,

forty years... I've been very fortunate that some works of mine that

I wrote many years back are still being played and recorded and recognized.

The thing that makes a work durable, I suppose, is something that we cannot

control. It's a creative act that has to have a certain kind of truth

to it that stands the test of time, and is reacted to by listeners over a

period of time. More than that I cannot say. One could diagram

it and say, "Well, this is the mixture that makes something." We can

get the recipe in a general sense. In music and art and literature,

I think we all recognize the fact that if something has inventiveness and

creativity and character and identity, it stands a very good chance of becoming

part of an experience that goes over a number of generations.

MG: I wish we knew because then all of us could write every

piece to be durable. It doesn't always come out that way. You

write a number of works and if you're lucky, a few of them are durable.

And even that's a relative term. It could last ten years, twenty years,

forty years... I've been very fortunate that some works of mine that

I wrote many years back are still being played and recorded and recognized.

The thing that makes a work durable, I suppose, is something that we cannot

control. It's a creative act that has to have a certain kind of truth

to it that stands the test of time, and is reacted to by listeners over a

period of time. More than that I cannot say. One could diagram

it and say, "Well, this is the mixture that makes something." We can

get the recipe in a general sense. In music and art and literature,

I think we all recognize the fact that if something has inventiveness and

creativity and character and identity, it stands a very good chance of becoming

part of an experience that goes over a number of generations.

BD: Were you ever surprised that one of your pieces and not another was particularly durable?

MG: Yes. I think all composers feel that way sometimes. With the perspective of time, the great geniuses - such as Mozart and Beethoven - have created works that are obviously durable. However, even within those, it's interesting that certain works get more performances than others. Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is almost his signature that we recognize, and that probably gets more performances than his other works.

BD: Is there any chance that it gets played too much?

MG: Some people feel there is that possibility. It's interesting and I've often thought about it. There are a number of symphonic pieces that are known as 'chestnuts.' Tchaikovsky wrote three symphonies before he got to his fourth, fifth and sixth, and those are certainly chestnuts, or war horses. Also Dvořák's New World Symphony . . .

BD: What I'm leading into is how can we expand the repertoire to get a few more chestnuts, as well as a few more other things played?

MG: That's hard to come by, and there's no way of really knowing what works written today will endure. And when I say 'today,' I don't mean literally today, but in the sense of this period of our time. First of all, if we're talking about American composers, Copland, obviously, has a durability and has survived as a creative identity over many, many years. Gershwin, too. I'm mentioning some obvious names now.

BD: I would think Morton Gould fits into that category.

MG: Well, I don't know. Quite honestly, I don't think of that. I've never thought of myself in terms of history. Perhaps there are other composers who do have a sense of their place, and they might be able to give you a more positive answer than I can. I don't think of myself in that sense. Who knows? All I know is that I'm here today and I've been here for a long time, but only because I'm older. There's no way of knowing and I don't think about it. I enjoy what I do. Music is my life blood and I react to musical sounds of all kinds, all sorts. I'm curious about the world around me, the wonderful and exciting things that have been going on over the last number of years. There's an outburst of activity in this country, not only in music, but in art, painting, sculpture, literature, etc. The tremendous variety of expression of all kinds, from pop to serious - and those are terrible words and I hate them - from light to heavy, from symphonic and chamber music, to mixed media, crossover, fusion. Even rock has diversity from soft rock to hard rock and acid rock.

BD: Where is it all going?

MG: It's all going. I think it's always in motion. We're very close to it and we tend to get hung up on categories. Years ago there was swing and bop and bebop. Now there's punk and funk and metal and rap, gospel and country, soul... These are all words and categories that, in a sense, are transient. But within those categories there's a tremendous creative potency, and out of a number of works done within each category, just a very few of them will have the durability that we're talking about to become part of our language, part of our vernacular. There were hundreds of other composers writing at the time of Beethoven who have disappeared. We don't know of them, or we know of them vaguely. They might be curiosities today, and some of them were very good, by the way.

BD: Should we ever play those curiosities?

MG: It depends. Every now and then we see somebody come along from an older period who re-emerges. I'm not a musicologist and don't pretend to be that kind of person. I never had the time, but I'd be curious to see and hear works done in Beethoven's style or Mozart's style by colleagues of theirs, by fellow travelers. Every now and then I hear a work from the eighteenth century or the seventeenth century by a relatively unknown, obscure composer, and it's good, but it doesn't have that kind of total creative character that puts it in a class with a Beethoven or a Mozart.

BD: Without specific names, are we getting works on that level today?

MG: I don't know. There's a pretty good chance that we are, but, even though it's a cliché, the real judge is time, not a human being. I am not judgmental, but I have colleagues who would tell you flat out that only garbage is being done now. Nothing worth saving, with the exception of themselves, perhaps. Or they might say such and such is a masterpiece or so and so is a master composer, but they would be contradicted by a colleague who is just as knowing as they are, but who has different tastes. In our time, besides Copland whom I mentioned earlier, Stravinsky is an obvious example who stays with us. Also Bartók and Samuel Barber. In the popular field, I was part of the celebration of Irving Berlin's 100th birthday. He has been part of the previous time and also the present time, and will go into the future. The historic program that we did for him at Carnegie Hall, the amazing words and music that he contributed is not only a musical experience but a human experience. It's mind buckling. There's an example of a creative output that has gone beyond any particular fashions or trneds or anything like that. Getting back to what we were talking about before, if one was able to say, "This is what makes this kind of music and words durable," I suppose everybody could do it.

BD: Then where is the balance between inspiration and technique?

MG: That's a very interesting question. One can do a whole

essay on that. Is it the technique, or is it the bad element that you

cannot see. You can sometimes see the technique. In a sense,

you can see the machinery. Like a stunning bridge, you might be able

to see the specifics. You can see there are cables and so on, but what

sets this bridge apart from other bridges? The totality there is a

concept that goes beyond the machinery and beyond the technique. That

also gets very vague. I've said this before and it's not an original

thought, but one of the things about art - and especially about music - is

that it is intangible. You don't see it. You can't touch it,

but for you, it's valid.

MG: That's a very interesting question. One can do a whole

essay on that. Is it the technique, or is it the bad element that you

cannot see. You can sometimes see the technique. In a sense,

you can see the machinery. Like a stunning bridge, you might be able

to see the specifics. You can see there are cables and so on, but what

sets this bridge apart from other bridges? The totality there is a

concept that goes beyond the machinery and beyond the technique. That

also gets very vague. I've said this before and it's not an original

thought, but one of the things about art - and especially about music - is

that it is intangible. You don't see it. You can't touch it,

but for you, it's valid.

BD: So what is the purpose of music?

MG: Music, as we know it, and we're talking about works that have been consciously created, because in a general sense, one could say music is a guttural sound; this is where it starts. Music, basically, is the sound of the human condition. From the simplest reactive sounds of pain, of glee, of sadness, to what I would call a self-conscious organized sound. This is the composer or the lyricist or both. When one consciously writes a song, he or she distills that sound that he or she has inherited. The lineage or aural experience is deep seated, deep rooted. We still respond to drums, don't we? We respond to percussion and percussive things. Some of our popular music has obvious manifestations with that. Some people say, "This popular music is noisy." Why do the young people react to this? This is the drum; this is the kind of visceral impact that we all react to on different levels. In the more complex, more complicated expressions of music - in the making of a symphony and so on - you're dealing with a big piece of musical architecture. But also, within that, there is the physical impact. You go to hear a symphony orchestra and there is a visceral thing. An exciting concert with a symphony orchestra is a visceral as well as an intellectual and emotional experience. There's a wonderful richness of sound that comes out, or a tremendous explosive impact that it might have. What makes one piece not have that and another piece have it is so dependent on so many factors. It might be how it's played, where it's played, the kind of audience that's listening to it, the individual reaction. You and I might listen to the same piece of music and react differently to it, and that's got nothing to do with how knowledgeable or not your are about the music. Your reaction is as valid as mine. I, as a professional musician - a conductor or performer - might have a colleague and we might not like the same composer. I might find a certain composition not particularly exciting to do or to perform, and he might say it's a great piece, a piece he would want to do. A lot of it is individual taste.

* * * * *

BD: Coming back to your own compositions, when you're writing,

are you always in control of the pencil, or are there times when the pencil

is in control of you?

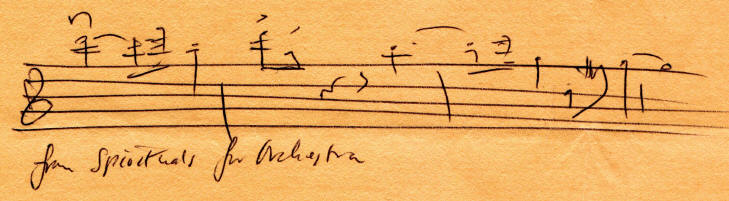

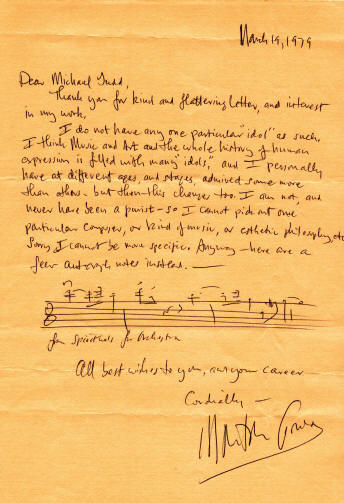

[From a hand-written letter which is reproduced in full below]

MG: [laughs] You're dangerous. You must be a musical CIA. That's a very, very potent question. Basically, you have to be in control of the machinery of putting down notes, but I know what you're getting at. It's a strange combination inside one's head. We all have the availability of a million different kinds of sounds, a million ways of doing a particular couple of bars, for instance. Now a number of factors come into play. One of them is the particular talent of the creator. A large talent, a big talent has ingested what has come before in music, and can transform it into his own particular kinds of patterns. In a sense, it's a terrible word to use, but you spew it out. You recycle. In a way, it's recycling of what one has absorbed and has heard before. It's recycled so that it comes out in a way that listening to it not only communicates, but also gives the illusions that this is something you have never heard before. This is very deceptive. I am a composer, and even though I'm a pianist and can improvise, I do not use a piano when I write. I can sit down and make up a piece, a sonata or so on, extemporaneously, but I've always worked away from the piano because I hear the sounds of the orchestra. I hear all of these things because I'm basically an orchestral writer. There have been some excellent composers, wonderful composers, who have used the piano and some terrible composers who have used the piano. There are also good ones and bad ones who don't use the piano. It's a convenience, but not needing it means I'm not dependent on it. When I sit in a hotel room, I can work. When I fly on a plane, I can work. I never have time, but if I had time, I could sit down and write a piece today. I hear sounds in my head all the time, as is the case with most recognized composers, or people who have established themselves as professional composers. I have always worked on commissions and therefore have deadlines.

BD: You must have a pile of commissions and continue to get requests. How do you decide which ones you'll accept and which ones you'll turn aside?

MG: Certain commissions I do not accept for one reason or another. I can only accept commissions that fit into a schedule. You can't do them when six or seven deadlines are going to happen on the same night. You cannot be ready in a limited amount of time. You have to spell yourself. But the commission itself is an amazing stimulus to creativity, and the pressure of a deadline can really do amazing things to most creative people who otherwise would, perhaps, contemplate the possibility of a work but can't actually get themselves to sit down and do it. You have to sit down and start from nothing.

BD: Does the commission force you to have thoughts, or does it force you to organize the thoughts you already have?

MG: Not necessarily. You might not have thoughts.

It can work both ways. In my case, often the commission has nothing

to do with the thoughts I was having. If you get a specific commission,

that's what you write. I recently had a commission for a Flute Concerto

for the Chicago Symphony with its principal flutist Donald Peck and conductor

Sir Georg Solti.

It was done here and went very well. I might have had other ideas at

that point, but the commission and the deadline force you to organize yourself.

This is the way I've gone. It's easy to sit in front of blank paper

with the thirty or forty staffs, and think, "I've got to fill this all up

with notes." I must confess that sometimes I can't think of one dot

at the moment, or at least one that I would want to put down. And then

you'll be up at two or three in the morning and you start to think negatively

and almost pity yourself. Don't forget, in the writing of music you're

doing it the way they did it a thousand years ago. Despite all our

technology, you have to write every note. Maybe someday it will happen

that we can project it out of the mind onto the paper, but so far, you have

to write every note. Then I go through a very low period where I think

I'm never gonna come up with anything. I should never have accepted

the commission and how will I ever make the deadline? Oddly enough,

just the sheer act of using that part of my brain begins to generate some

kind of creative life in my inner ear, and things start to happen.

I suddenly start to get ideas and suddenly get a general sense of what the

piece might be. It's like visualizing a bridge in a vague way.

You don't know the specifics and you're not too sure even where it's

gonna land or where it's going or what it's connected, but it's a vague shape

of sounds. And then, bit by bit, you begin to get more specific, and

you hear a sequence or a passage and get thoughts, and then you begin to

get blocks of these things and start to connect the tissues. Then it

starts to roll, and that is the greatest experience, a euphoric experience.

You've gotten past midnight and it's two or three in the morning and you really

want to go to sleep, but you gotta force yourself to do this, and you have

to forget the fact that you've been pitying yourself, and that every civilized

person is in bed and asleep and you're sitting up, and then, suddenly, things

start to roll out. This answers your question about the pencil because

you begin to get things that you have not consciously thought of. One

might call that inspiration, I suppose, but that's a vague word. Basically,

the inspiration comes from forced feeding and then it starts to roll.

Now it doesn't necessarily roll without stoppages, you know. It's just

the idea. We know of work stoppages. Well, creative stoppages

are just like work stoppages. You're rolling and suddenly you can't

go further.

MG: Not necessarily. You might not have thoughts.

It can work both ways. In my case, often the commission has nothing

to do with the thoughts I was having. If you get a specific commission,

that's what you write. I recently had a commission for a Flute Concerto

for the Chicago Symphony with its principal flutist Donald Peck and conductor

Sir Georg Solti.

It was done here and went very well. I might have had other ideas at

that point, but the commission and the deadline force you to organize yourself.

This is the way I've gone. It's easy to sit in front of blank paper

with the thirty or forty staffs, and think, "I've got to fill this all up

with notes." I must confess that sometimes I can't think of one dot

at the moment, or at least one that I would want to put down. And then

you'll be up at two or three in the morning and you start to think negatively

and almost pity yourself. Don't forget, in the writing of music you're

doing it the way they did it a thousand years ago. Despite all our

technology, you have to write every note. Maybe someday it will happen

that we can project it out of the mind onto the paper, but so far, you have

to write every note. Then I go through a very low period where I think

I'm never gonna come up with anything. I should never have accepted

the commission and how will I ever make the deadline? Oddly enough,

just the sheer act of using that part of my brain begins to generate some

kind of creative life in my inner ear, and things start to happen.

I suddenly start to get ideas and suddenly get a general sense of what the

piece might be. It's like visualizing a bridge in a vague way.

You don't know the specifics and you're not too sure even where it's

gonna land or where it's going or what it's connected, but it's a vague shape

of sounds. And then, bit by bit, you begin to get more specific, and

you hear a sequence or a passage and get thoughts, and then you begin to

get blocks of these things and start to connect the tissues. Then it

starts to roll, and that is the greatest experience, a euphoric experience.

You've gotten past midnight and it's two or three in the morning and you really

want to go to sleep, but you gotta force yourself to do this, and you have

to forget the fact that you've been pitying yourself, and that every civilized

person is in bed and asleep and you're sitting up, and then, suddenly, things

start to roll out. This answers your question about the pencil because

you begin to get things that you have not consciously thought of. One

might call that inspiration, I suppose, but that's a vague word. Basically,

the inspiration comes from forced feeding and then it starts to roll.

Now it doesn't necessarily roll without stoppages, you know. It's just

the idea. We know of work stoppages. Well, creative stoppages

are just like work stoppages. You're rolling and suddenly you can't

go further.

BD: The brain goes on strike?

MG: Something happens and you get hung up. Sometimes I've been hung up on two bars. I can't decide. Remember, what you're doing is a simultaneous activity. If one could look into a creative brain, it would be fascinating to see all the things that are operating at different levels. You are throwing out sparks and yet you are discriminating. It's a selective act because you have to decide. Composing is as much deciding what you're not going to do as what you will do. It is a bigoted act because you have at your disposal all kinds of expressions, all kinds of gestures, all kinds of paths, and out of the limitless supply, you select certain routes.

BD: Hopefully what you're selecting is quality.

MG: Hopefully what you're selecting is quality, yes. And it not necessarily is.

* * * * *

BD: You compose and you conduct. Are you the ideal interpreter of your work?

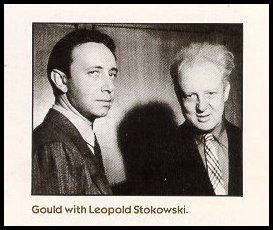

MG: Not necessarily. I've been very fortunate. My

works have been widely played, and the world premieres of my big works have

been done, for the most part, by some of the great conductors of the past

and present, including Stokowski, Toscanini, Mitropoulos, Rodzinsky.

I've had a wide range of exposure and have had the experience of hearing conductors

set a standard. Stokowski was a creative kind of a conductor in a sense

that he could sometimes do slightly unorthodox things in his approach to

music making. A conductor like that can do your work and I would listen.

I would hear it and would say, "Hey, that's a very good way of doing it.

Why didn't I think of that as a performer?" There are a number of composer/conductors

who are not necessarily real conductors as such. I was, and am, a conductor

who could stand a lot of repertoire. Oddly enough I have found that

when I do programs where a work of mine is included, I tend not to give it

too much time. I'm anxious. I feel a responsibility to the other

composers rather than to myself, and sometimes, oddly enough, I'm a little

bored with my piece. I know the piece and it's not a challenge.

It's a challenge to do a good performance, a recognized performance, of a

chestnut, like the New World Symphony. I remember, many, many

years ago, doing a program with one of the major orchestras that had some

difficult works on it. There were some contemporary works by colleagues

of mine and one of my own. I paid a lot of attention to them and knew

them cold. They were very complicated and the orchestra was very impressed

with the way I handled them. But when I got to my piece, I had not

studied it. I had written it a long time ago and had forgotten how difficult

my piece was. When we went out to lunch together, the concertmaster

said, "I can't believe it. Why didn't you study your own piece?

We thought you were great with the way you handled everything else, but you

really didn't know your it, did you?" I said, "No."

MG: Not necessarily. I've been very fortunate. My

works have been widely played, and the world premieres of my big works have

been done, for the most part, by some of the great conductors of the past

and present, including Stokowski, Toscanini, Mitropoulos, Rodzinsky.

I've had a wide range of exposure and have had the experience of hearing conductors

set a standard. Stokowski was a creative kind of a conductor in a sense

that he could sometimes do slightly unorthodox things in his approach to

music making. A conductor like that can do your work and I would listen.

I would hear it and would say, "Hey, that's a very good way of doing it.

Why didn't I think of that as a performer?" There are a number of composer/conductors

who are not necessarily real conductors as such. I was, and am, a conductor

who could stand a lot of repertoire. Oddly enough I have found that

when I do programs where a work of mine is included, I tend not to give it

too much time. I'm anxious. I feel a responsibility to the other

composers rather than to myself, and sometimes, oddly enough, I'm a little

bored with my piece. I know the piece and it's not a challenge.

It's a challenge to do a good performance, a recognized performance, of a

chestnut, like the New World Symphony. I remember, many, many

years ago, doing a program with one of the major orchestras that had some

difficult works on it. There were some contemporary works by colleagues

of mine and one of my own. I paid a lot of attention to them and knew

them cold. They were very complicated and the orchestra was very impressed

with the way I handled them. But when I got to my piece, I had not

studied it. I had written it a long time ago and had forgotten how difficult

my piece was. When we went out to lunch together, the concertmaster

said, "I can't believe it. Why didn't you study your own piece?

We thought you were great with the way you handled everything else, but you

really didn't know your it, did you?" I said, "No."

BD: Did you rectify the situation before the concert?

MG: Before the performance I'm sure I knew every line, but I think a composer will bring certain things to a piece, but that depends on how good he is technically, whether you're the composer or not. If you're conducting, there's a way of getting an orchestra to play and a way of getting them not to play.

BD: What advice do you have for young conductors?

MG: [laughing] Sell insurance. Seriously, there are a lot of young conductors and some of them are really very good. It's a tough field and unless you have a real natural talent - hopefully a genius - it's very difficult. Everybody wants to be the conductor of the New York Philharmonic or the Chicago Symphony, or Boston or Philadelphia or Cleveland, but those are a very few posts and the competition is very keen, and you're competing with tremendous, seasoned and proven virtuoso conductors. So it's hard to answer that question without knowing who the specific young conductor is and what his or her background is.

BD: Are you pleased with what you see coming along, though?

MG: Generally, yes. I've heard some very impressive things. Conducting really takes a long time, even if you're a very gifted young conductor. It takes a lot of experience, a lot of seasoning. There are some wonderfully gifted women conductors now, some very gifted black conductors, latino conductors...

BD: It is really cutting across all the lines.

MG: Yeah, absolutely, absolutely, and it reflects what is happening to our own society. At long last, a lot of these barriers are coming down or melting. They're not all gone and the residue will be there for a long time, but it's happening, it's moving. Regardless of anything else, at this point there would be no ethnic obstructions to somebody with a great talent getting a post. It's happened and there are examples around.

BD: What advice do you have for young composers coming along?

MG: Young composers have to do what all composers have to do whether they're young or old, but certainly for the young person. The creative mind, the creative spirit, has to try to find its own truth, but beware of trends, fashions and dogmas.

BD: Not to fall into those traps?

MG: Not to fall into those traps, and that's a very difficult thing for all of us. We all want to be liked, and if we see that we're living in a period where tremendously complicated music and pieces with high density are the 'in thing' and getting the critical kudos and approbations, it's hard not to think, "Maybe I ought to write like that to be accepted and recognized." But that might be something that is already on the way out, or even gone. The other extreme is the so-called minimalist school. All of these ways, all of these categories, all of these textures have a creative value. They're all valid. It depends how they're used and it depends on the individual creative talent with his or her own particular identity and character. And in order to do that - assuming one has the talent - you have to find what is your fashion, what is your truth. In a sense, it might be fashionable to wear a certain kind of clothing, but the well-dressed person is somebody that always looks well-dressed, and who doesn't put on this week's fashion or style in which he or she might look like an idiot because it doesn't go with them. I have often cited the fact that some years back we suddenly had the thing about the Nehru Suit. I had some friends who bought a whole wardrobe and walked around in Nehru Suits. Well they came from a different culture and they really looked as if they were aborated. It didn't go with them.

BD: That fad lasted about a week, as I remember.

MG: Exactly. It was all hype and it went out fast. I have some friends who really stocked up and then asked what they were going to do with all those suits.

BD: I think Johnny Carson wore one once on his show.

MG: Really? Just the image of him in a Nehru Suit is funny. But the same thing happens in the arts, except it takes a little longer to puncture that falsity. There's a tendency in music for people to say, "Well, you don't understand it and it might look foolish now, but it will be recognized." Sometimes it's true, and this is a very involved answer to a simple question that you posed, but a very good question about what I would tell a young composer. First you must find out who you are. You must always be curious and that doesn't mean you always stay in the same place. Use whatever you can from the minimalist to the maximalist, from the simple to the complex. Whatever feeds you, whatever you find you can put together, but it has to be in your own image, not in somebody else's image. The other thing for the young composer of symphonic or concert music, is that the financial returns, the economic returns are very limited. I think that the young composer should have a teaching degree, unless you come from a wealthy family or marry wealthy. Then you have a number of choices, but otherwise, you must have some kind of economic flooring.

BD: Have you ever taught?

MG: No, I've never taught, but I did other things, you see.

I used part of my talent as an orchestrator. I do a lot of arrangements.

I am also a conductor. I took that route, but I was sort of unique in

that sense. Most of my colleagues taught and many of them teach to

this day. There's nothing wrong with that. As a matter of fact,

I never had the patience for it, but one of the things I do regret is that

I didn't teach. I have tremendous admiration for all teachers, for

educators. I think the teacher in any subject is the most important

human being in our society. This is the person who turns the young human

being on or off, and I envy those of my colleagues who do it. I see

them, and people come up to them and say, "I studied with you," or "I studied

with so and so. I was a student." This must be a very rewarding

thing to feel, that you have enabled another human being to fulfill himself

or herself. I'm giving you my own emotional and personal reaction,

but economically, I certainly couldn't survive because Stokowski was playing

my music. This was in the 1930s, and in those days, American composers

didn't even get paid when an orchestra played their music. This was

before ASCAP or any of the performing rights societies were even licensing

or collecting in this area. I came from a poor family, so I had to

find a way of surviving economically. Not only myself, but I was supporting

my whole family; my mother, my father, an aunt, a grandma and three brothers.

I did it through playing the piano, and I was a pretty good pianist.

That afforded me a living, and I had different jobs. Then, through

radio, I became a conductor and arranger. This was live radio which

we don't have today, so that route is closed off. But even then, I

realized I was about the only one who went that route. But whatever

you do, you need to have an economic base, or some means of economic survival.

MG: No, I've never taught, but I did other things, you see.

I used part of my talent as an orchestrator. I do a lot of arrangements.

I am also a conductor. I took that route, but I was sort of unique in

that sense. Most of my colleagues taught and many of them teach to

this day. There's nothing wrong with that. As a matter of fact,

I never had the patience for it, but one of the things I do regret is that

I didn't teach. I have tremendous admiration for all teachers, for

educators. I think the teacher in any subject is the most important

human being in our society. This is the person who turns the young human

being on or off, and I envy those of my colleagues who do it. I see

them, and people come up to them and say, "I studied with you," or "I studied

with so and so. I was a student." This must be a very rewarding

thing to feel, that you have enabled another human being to fulfill himself

or herself. I'm giving you my own emotional and personal reaction,

but economically, I certainly couldn't survive because Stokowski was playing

my music. This was in the 1930s, and in those days, American composers

didn't even get paid when an orchestra played their music. This was

before ASCAP or any of the performing rights societies were even licensing

or collecting in this area. I came from a poor family, so I had to

find a way of surviving economically. Not only myself, but I was supporting

my whole family; my mother, my father, an aunt, a grandma and three brothers.

I did it through playing the piano, and I was a pretty good pianist.

That afforded me a living, and I had different jobs. Then, through

radio, I became a conductor and arranger. This was live radio which

we don't have today, so that route is closed off. But even then, I

realized I was about the only one who went that route. But whatever

you do, you need to have an economic base, or some means of economic survival.

BD: You've got to support your habit.

MG: Exactly. That's very well put. [laughs] I think I'm gonna quote that and never give you credit for it!

BD: That's okay. It got it from my old teacher, Thomas Willis, who was the Senior Music Critic of the Chicago Tribune. I was his Graduate Assistant at Northwestern University. Later, I taught in the Evanston Public Schools for a couple years and then went to WNIB.

* * * * *

BD: A lot of your music has a patriotic nature to it. Is that something special for you?

MG: It's not conscious. In other words, I don't sit down to it, but you see, I'm one of these composers who definitely reflects the sounds around me, and I find them stimulating. I use vernacular and I am very moved and touched , as we all are, as a matter of fact, by the sound of spirituals, by black music, by country music, by popular music, by the man, many different sounds that have come out of this country, many of which are already a mix of things that have come from Europe and have been absorbed here. They are recycled and transformed and so on and so on. Yes, I react to that. There are composers who don't, but I find that a stimulating thing to do and I'm very aware of the fact that I supposedly reflect kind of an American sound. That, in itself, does not necessarily make for good music. You can be for virtue and not necessarily be a very creative person. There again, regardless of what the music reflects, it has to have its own creative truth in it. I've written a great deal of music that could be called very American and probably could be called very patriotic. I would hope that's not in a chauvinistic sense and not in a narrow sense, but in an all-embracing sense of what this country represents. The richness of it, the diversity. We have a lot of things that are wrong, that have been wrong, that are still wrong, that have to be improved and fixed. But on a relative scale, the wide scope, the freedom - a word that has been bantered about - is a very real thing to express ourselves and to express really anything we want to without being subject to any kinds of restrictions or anything like that. We tend to forget that. I don't mean to be a chauvinistic flag waver, but in a certain sense, I am, damn it. There's nothing wrong with it because I feel we tend to forget and take certain things for granted. In that sense, I feel very strongly. I definitely feel a patriotism.

BD: Thank you for all you have given - your music, your conducting, your ideas, your help.

MG: Oh, how nice of you to say. As I told you before,

I feel lucky to do what I like to do, plus the fact that it's the only thing

I know how to do.

=== === === === ===

--- --- ---

=== === === === ===

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This interview was held at the Hilton Hotel in Chicago on June 18, 1988.

Portions were aired on WNIB later that year and several times thereafter,

and later on WNUR, and on Contemproary Classical Internet Radio.

A small portion was also included in the 75th birthday tribute which was part

of the entertainment package placed aboard United Airlines, and also placed

aboard Air Force One, the Presdential Jetliner. A similar tribute

(with music but no interview) was placed aboard Eastern Air Lines,

and partial transcript was published in Nit&Wit Magazine.

This full transcript was posted on this website in January, 2007.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

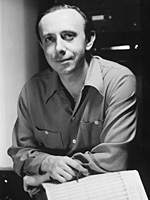

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.

| [Biography from his publisher, G. Schirmer, Inc., dated April,

2002]

Morton Gould Born: 1913 Died: 1996 "Composing is my life blood," said Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Morton Gould. "That is basically me, and although I have done many things in my life - conducting, playing piano, and so on - what is fundamental is my being a composer." Capping a life full of achievements in all facets of music are Morton Gould's 1995 Pulitzer Prize for Stringmusic, commissioned by the National Symphony for the final season of music director Mstislav Rostropovich, and his 1994 Kennedy Center Honor in recognition of lifetime contributions to American culture. Born in Richmond Hill, New York, on 10 December 1913, Gould was recognized early on as a child prodigy with the ability to improvise and compose. At the age of six he had his first composition published. He studied at the Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School), but his most important teachers were Abby Whiteside (piano) and Vincent Jones (composition). During the Depression, Gould (still a teenager) found work in New York's vaudeville and movie theaters. When Radio City Music Hall opened, the young Gould was its staff pianist. By the age of 21 he was conducting and arranging a series of orchestral programs for WOR Mutual Radio. Gould attained national prominence through his work in radio, as he appealed to a wide-ranging audience with his combination of classical and popular programming. During the 1940s Gould appeared on the "Cresta Blanca Carnival" program and "The Chrysler Hour" (CBS), reaching an audience of millions. Gould composed Broadway scores (Billion Dollar Baby, Arms and the Girl), film music (Delightfully Dangerous, Cinerama Holiday, Windjammer), music for television (Holocaust, the CBS documentary World War I), and ballet scores (Interplay, Fall River Legend, and I'm Old Fashioned). His music was commissioned by symphony orchestras throughout the United States, the Library of Congress, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the American Ballet Theatre, and the New York City Ballet. Gould integrated jazz, blues, gospel, country-and-western, and folk elements into compositions which bear Gould's unequaled mastery of orchestration and imaginative formal structures. These instantly recognizable American sounds led to Gould's receiving three commissions for the US Bicentennial (including American Ballads, Symphony of Spirituals, and Something to Do). Always open to new styles, he incorporated a rapper/narrator into The Jogger and the Dinosaur and a fire department into Hosedown, both commissions for the Pittsburgh Youth Symphony. Among his last works are Stringmusic, Classical Variations on Colonial Themes, and Diversions for saxophone and orchestra. Ghost Waltzes was commissioned for the ninth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition (1993). Recent recordings of his music include American Ballads on Angel, Declaration Suite on BMG, Fall River Legend on Albany, Holocaust Suite and Of Time and the River on Koch, West Point Symphony on Mercury, and Concerto Grosso on Delos. His talents as an arranger are featured on a series of recordings recently re-released by BMG. As a conductor, Gould led all the major American orchestras as well as those of Canada, Mexico, Europe, Japan, and Australia. In 1966 he won a Grammy Award for his recording of Ives's First Symphony with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, a recording that led the way for a new appreciation of Ives's work. Gould received the American Symphony Orchestra League's 1983 Gold Baton Award. In addition to his Pulitzer Prize and Kennedy Center Honor, he was Musical America's 1994 Composer-of-the-Year. A long-time member of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers, Gould was elected president of ASCAP in 1986, a post he held until 1994. In 1986 he was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. He also served on the board of the American Symphony Orchestra League and on the National Endowment for the Arts music panel. His music is published by G. Schirmer, Inc.

|

| [From the Kennedy Center]

Morton Gould (composer, born December 10, 1913, Richmond Hills, New York; died February 21, 1996) Morton Gould was a prolific and versatile composer whose works throughout this century reflected the moods and outlook of this country in all its rough-and-tumble optimism. Like Gershwin, Copland, and Ives, Gould turned to the indigenous musical styles of the peoples of this country for inspiration--jazz, folk, hymns, spirituals, gospel, and Latin American music--and produces full-blown orchestral works that are immediately accessible and unmistakably American. Gould wrote in a wide range of genres, but he was best known for his orchestral works, which include scores for radio (American Symphonette, 1938), Broadway musicals (Million Dollar Baby, 1945), ballets (Fall River Legend, 1947), film (Windjammer, 1958), and television (Holocaust, 1978). As conductor, he led orchestras around the world and made first recordings of works by Shostakovich, Ives, and Copland. He was the oldest of four boys of a nonmusical family. A player piano in the living room was his earliest musical memory. A piano prodigy by the time he was 5, he played a concert at the Brooklyn Academy of Music during his first year in school which included his first composition. At 8 he was a scholarship student at the Institute of Musical Arts in New York City. Entering his teens, Gould's family faced financial difficulties. The player piano was sold, and he had to leave school to earn a living as a pianist for vaudeville acts, and giving recitals in which he improvised works constructed around themes contributed by the audience. Eventually he landed the job of staff pianist for the opening of Radio City Music Hall. The year was 1931, and he was 18 years old. Playing for shows at the nation's premier palace for pop entertainment while at the same time studying "serious" music with the likes of conductor Fritz Reiner kept him straddling the two very different worlds of music, which over the years he helped enormously to bridge. Gould next went into radio, in charge of music on the Mutual Radio Network from 1934-42, and in 1943 becoming music director of the popular "Chrysler Hour" on CBS. His audiences ranged in the millions. At the same time he was writing symphonic music that was being performed by such major conductors as Stokowski, Rodzinski, and Toscanini. His later compositional activities included a Cello Suite commissioned by the Chamber Society of Lincoln Center, I'm Old Fashioned, a ballet score for New York City Ballet based on the Jerome Kern song; America Sing, commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, a Flute Concerto commissioned by the Chicago Symphony, and a new work commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra to celebrate the composer's 80th birthday. Gould's keen interest in music education led him to give lectures on the art of composition, and he was often been found conducting an orchestra of his favorite musicians--students. His peers elected him to the presidency of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and ASCAP, the oldest performing rights organization in the world.

|