A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

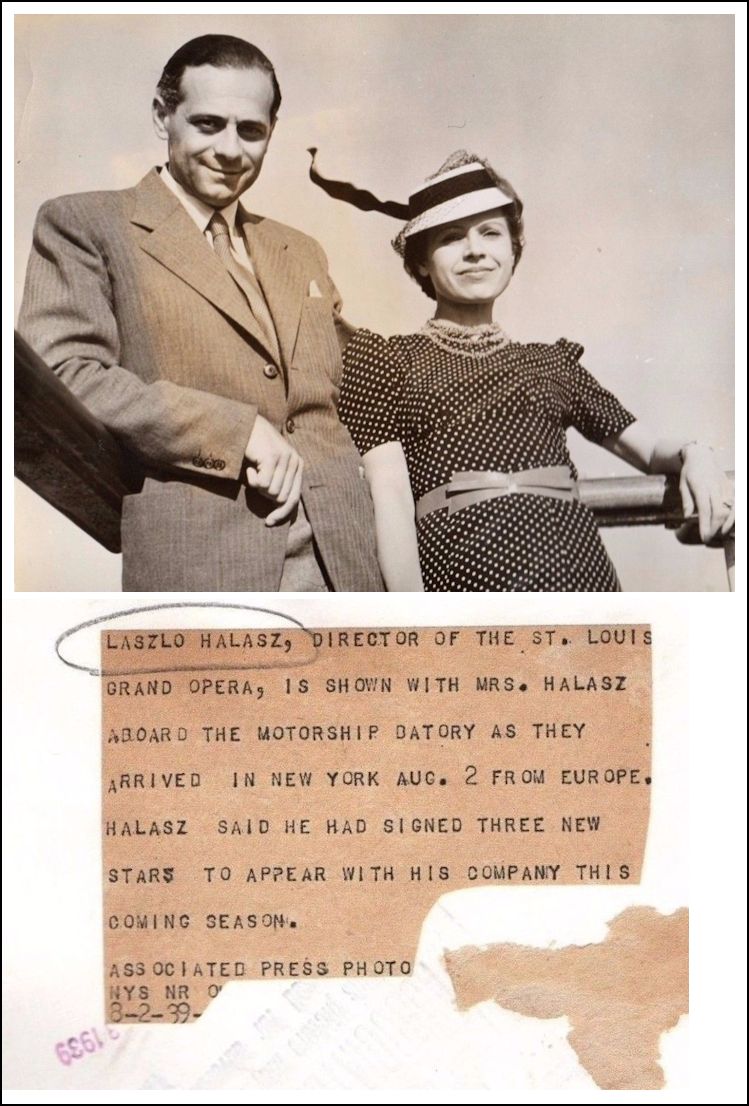

Laszlo Halasz (June 6, 1905 - October

26, 2001)

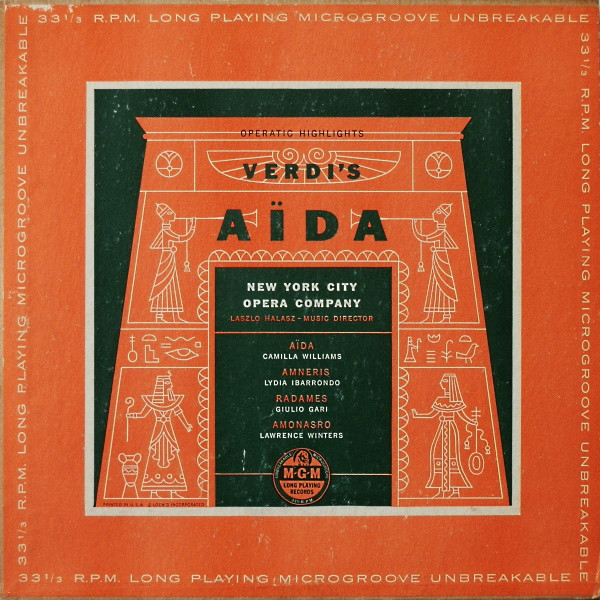

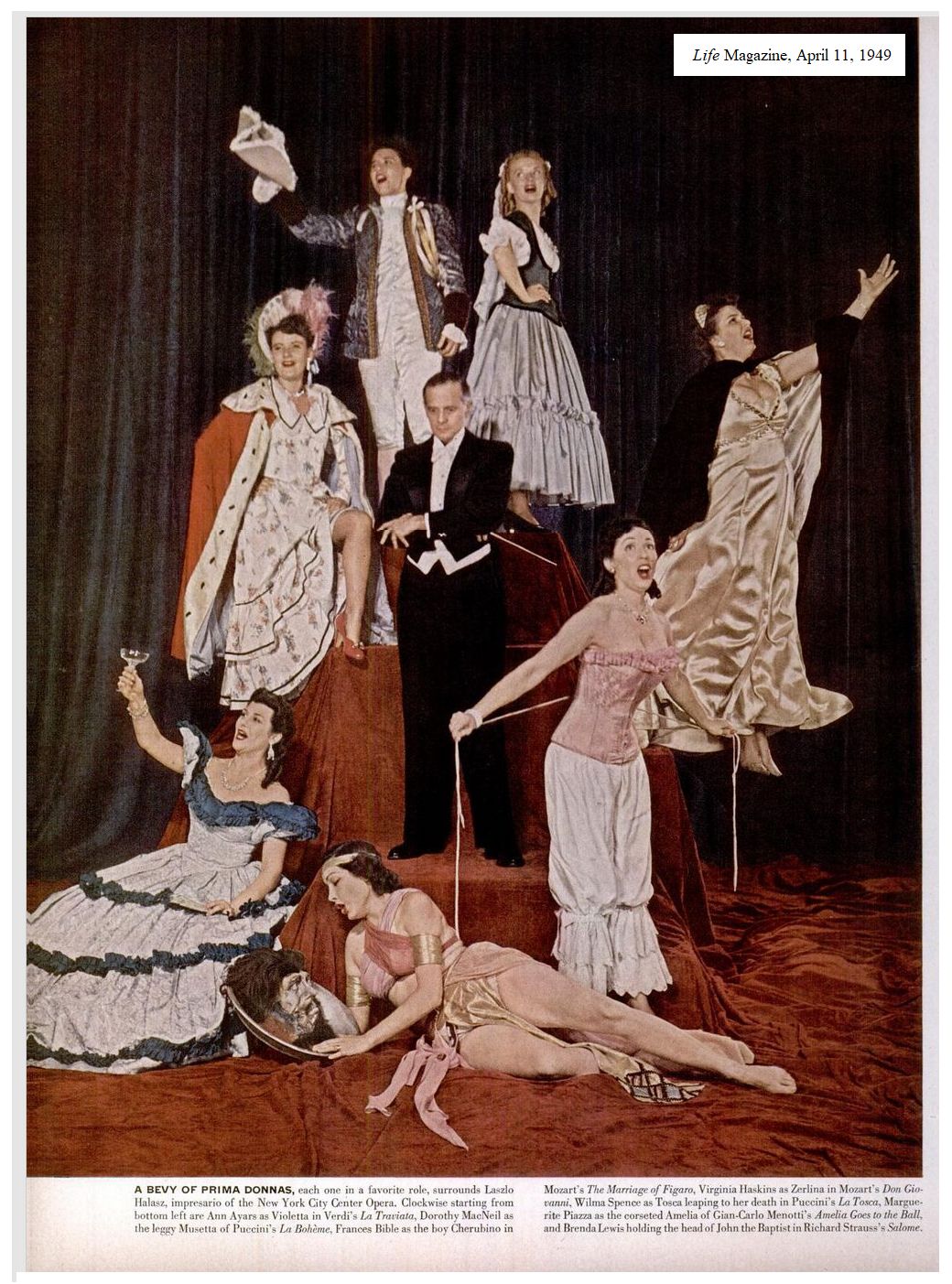

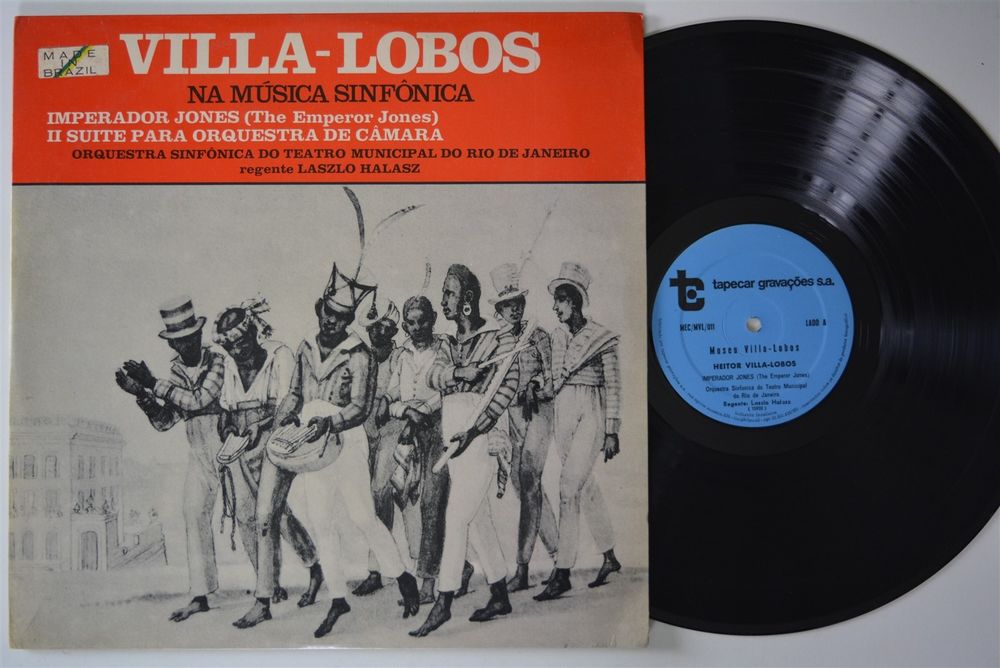

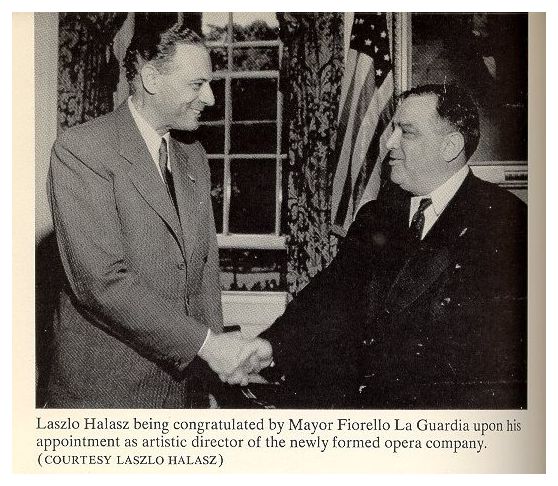

Halasz became the opera’s first director in 1943. During his eight-year tenure, the New York City Opera became an important training ground for young singers. The company also became an important venue for new works. Born in Hungary, Halasz studied at the Liszt Academy in Budapest, where his teachers included Bela Bartók, Ernst von Dohnányi, Leo Weiner and Zoltan Kodaly. He made his professional debut as a pianist in 1928, but in 1931 decided to focus on conducting. He came to

New York in 1936, and when the New York City Opera was formed

in the fall of 1943, Halasz was appointed its music director. The

company’s first season included productions of Puccini’s ``Tosca,″

Flotow’s ``Martha″ and Bizet’s ``Carmen.″ Halasz conducted the company’s first American premiere, Strauss’s ``Ariadne auf Naxos,″ in 1946, and the opera’s first world premiere, of William Grant Still’s ``Troubled Island,″ with a libretto by Langston Hughes. But the opera’s board was uneasy with Halasz’s ventures into modern opera. When the board insisted in 1951 that Halasz submit his repertory plans for approval, he resigned. The board ultimately relented, but when Halasz became involved in union disputes later that year, the board fired him. After leaving City Opera, Halasz began a second career as a record producer. He also conducted opera at houses in Frankfurt, Barcelona, Budapest, London and South America. As a teacher, he was on the conducting faculty at the Peabody Conservatory, in Baltimore, and the Eastman School of Music, in Rochester, N.Y.

-- Jeffrey Isner |

LH: Everything, because the airplane

was not yet an everyday thing. Flagstad was unexpectedly

asked to sing at the Met the night before. So, she took a train,

arrived at 2 o’clock in St. Louis, and missed the dress rehearsal.

We had a piano rehearsal, and she went onto perform it. The

prompter was a young conductor and chorus director, and I asked him

to keep track of how many mistakes she would make. She made one

in the whole evening, and was one of the saints of the profession.

LH: Everything, because the airplane

was not yet an everyday thing. Flagstad was unexpectedly

asked to sing at the Met the night before. So, she took a train,

arrived at 2 o’clock in St. Louis, and missed the dress rehearsal.

We had a piano rehearsal, and she went onto perform it. The

prompter was a young conductor and chorus director, and I asked him

to keep track of how many mistakes she would make. She made one

in the whole evening, and was one of the saints of the profession.| Jean Paul Morel (January

10, 1903 in Abbeville – April 14, 1975 in New York City) was a French-born

naturalized-American conductor. He served on the conducting staff

of the New York City Opera from 1946-1951. He had a long association

with the Metropolitan Opera as their chief conductor of the French

repertoire from 1956-1971. He also taught for 22 years at Juilliard

School, where he was the director of the Juilliard Orchestra and professor

of conducting. Several of his pupils became famous conductors, including

Herbert Blomstedt,

James Levine,

Jorge Mester,

and Leonard Slatkin. |

BD: What kind of casting did you

have for the Ring?

BD: What kind of casting did you

have for the Ring? BD: Are the operas of Strauss a continuation of

the Wagnerian tradition?

BD: Are the operas of Strauss a continuation of

the Wagnerian tradition?|

The opera received its premiere performance on December 30, 1921 at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, conducted by Prokofiev. It received its first Russian production in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) in 1926 and has since entered the standard repertoire of many opera companies. The initial criticisms of the Chicago production were generally harsh, e.g., "it left many of our best people dazed and wondering", "Russian jazz with Bolshevik trimmings" and "The work is intended, one learns, to poke fun. As far as I am able to discern, it pokes fun chiefly at those who paid money for it". The newspaperman and author Ben Hecht, however, gave it an enthusiastic review: "There is nothing difficult about this music – unless you are unfortunate enough to be a music critic. But to the untutored ear there is a charming capriciousness about the sounds from the orchestra". The opera was not performed again in the United States until 1949

when the New York City Opera resurrected it. As staged by Vladimir

Rosing and conducted by Laszlo Halasz, the production was successful.

Life magazine featured it in a color photo spread. The

New York City Opera mounted a touring company of the production, and the

opera was again staged in New York for three successive seasons. Many of the costumes used for the original 1921 Chicago production

were discovered in a warehouse, and the New York City Opera used many

of them for lesser characters in the 1949 production. |

|

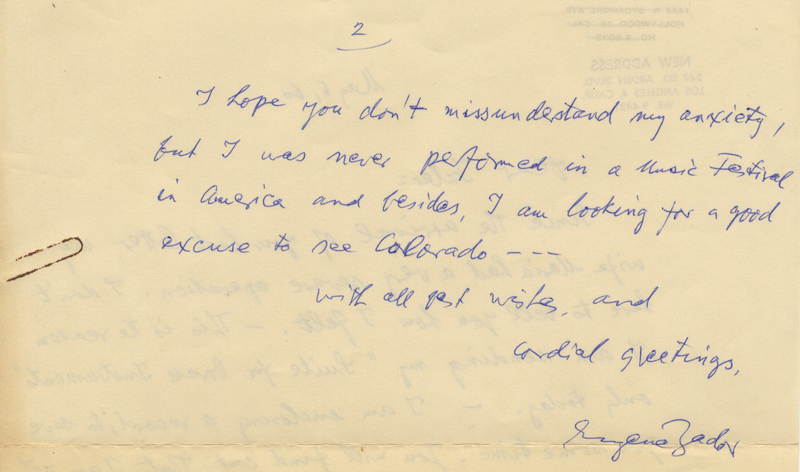

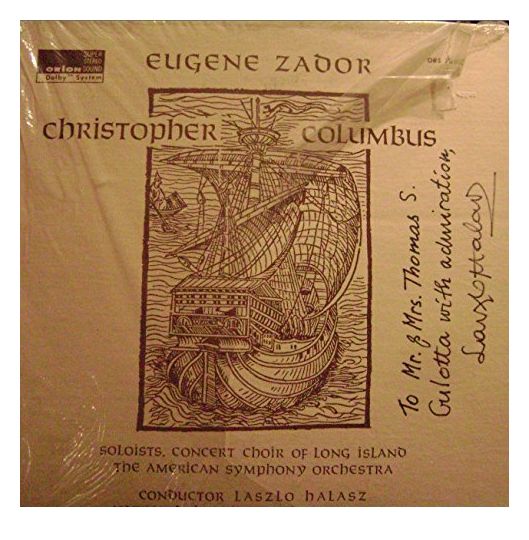

He studied at the Vienna Music Academy and in Leipzig with Max Reger. He taught from 1921 at the new New Vienna Conservatory, and later at the Budapest Academy of Music. On the outbreak of World War II he emigrated to the US, where he became a successful composer of film scores for Hollywood. He also wrote a number of operas in which the characterization and orchestration are worthy of note, and orchestral pieces in a style that owed something to Reger and Richard Strauss, including the popular Hungarian Caprice (1935) and concertos for such instruments as the cimbalom (1969) and accordion (1971). Although his operas are said to be strongly characterized and skillfully orchestrated, his compositional style remained within the late romantic language of Richard Strauss and Max Reger (he claimed to occupy a position "exactly between La Traviata and Lulu)".

Autograph letter signed "Eugene Zador" to "Tyler" [For sale by J&J Lubrano, Music Antiquarians] 2 pp. Large quarto. Dated [Los Angeles,] May 6, [19]60. In blue ink on personal stationery with Zador's California addresses printed and handstamped at head. With autograph corrections to printed address. Concerning the Suite for Brass Instruments (1960-61), which Zador hopes his correspondent, a brass player, will premiere at a music festival in Colorado. He is sending a piano recording of his "experimental" piece later than anticipated because his wife has just had a "severe operation." "... I am enclosing a record to save you some time. You will find out that I am not a pianist, in fact I never learned the piano, and sometimes I had to turn the pages too. Because it is an experimental work (though [!]absolut tonal), I feel that the world premiere should take place at a music festival... by writing the score myself, I saved about $150 – which I gladly would turn over to you to pay the other 6 brass players (but of course very confidentially)... I was never performed in a music festival in America and besides, I am looking for a good excuse to see Colorado... " Creased at central fold; blank left margin of verso lightly browned, with small paper clip stain not affecting text. The Suite for Brass Instruments (for four trumpets, four horns, three trombones, one tuba) comprises three movements, and "is intended as a real virtuoso display for brass performers." It is dedicated to Gustav Koslik (1902-1989), a noted Austrian conductor. Since its publication in 1961, it has appeared on many American concert programs, and was professionally recorded for the first time in 1967. |

BD: Is it a strong work?

BD: Is it a strong work?

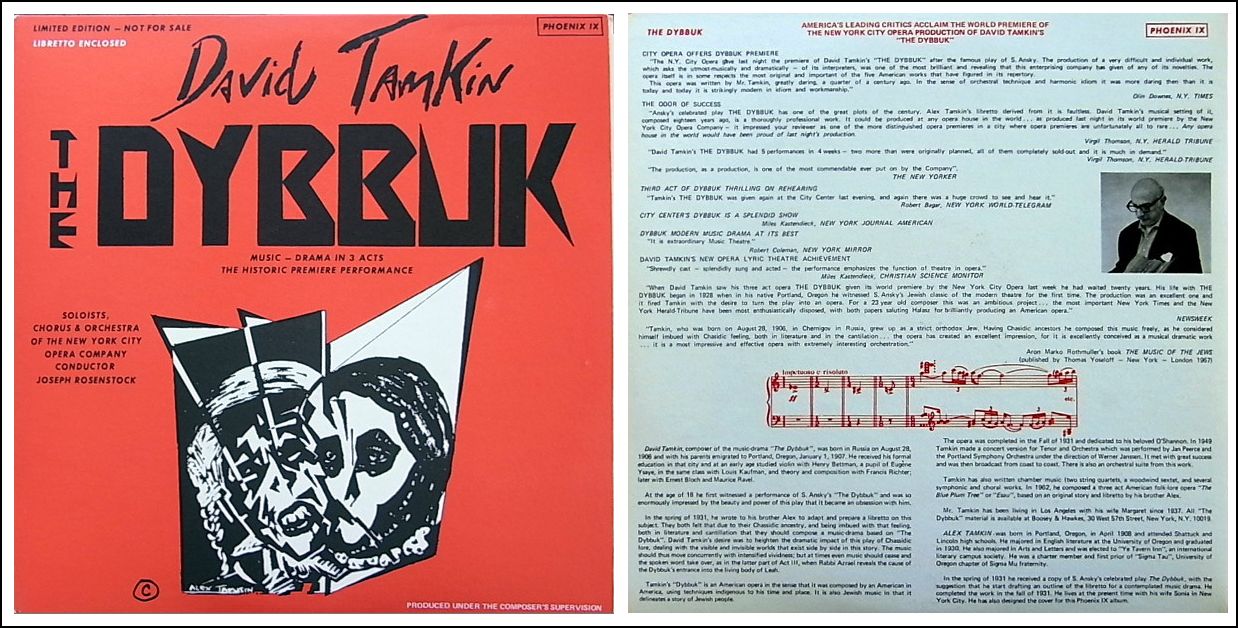

| The Dybbuk is an

opera in three acts by composer David Tamkin. The work uses an English

libretto by Alex Tamkin, the composer's brother, which is based on

S. Ansky’s Yiddish play of the same name. Composed in 1933, the work

was not premiered until October 4, 1951 when it was mounted by the New

York City Opera through the efforts of Laszlo Halasz. Prior to the premiere,

Tamkin extracted excerpts from the work and made a concert version in

eight movements for tenor and orchestra. This was given in Portland,

Oregon (where Alex Tamkin lived) in 1949, with Jan Peerce, conducted

by Werner Janssen,

and in New York City. The opera was originally supposed to premiere

at the New York City Opera in 1950 but was postponed for financial reasons.

The opera was also performed at the Jewish Community Center in Seattle

in 1963. According to The New York City Opera - An American Adventure by Martin L. Sokol, the world premiere performance was recorded by the Voice of America for overseas broadcast only. Years later, a group known as the Dybbuk Restoration Committee (or the Dybbuk Sponsoring Committee) negotiated with the unions involved and obtained permission to bring the performance out on records. It was not sold, but was given as a premium to supporters of the committee. The album consists of two records, and bears the number Phoenix IX. Later, they secured domestic broadcast clearance, and it was finally aired in the U.S. about twenty-five years after it took place.

Besides this setting of the play, there is a ballet by Max Ettinger (1947), and other operas including one by Shulamit Ran, (Between Two Worlds) premiered in Chicago in 1997. |

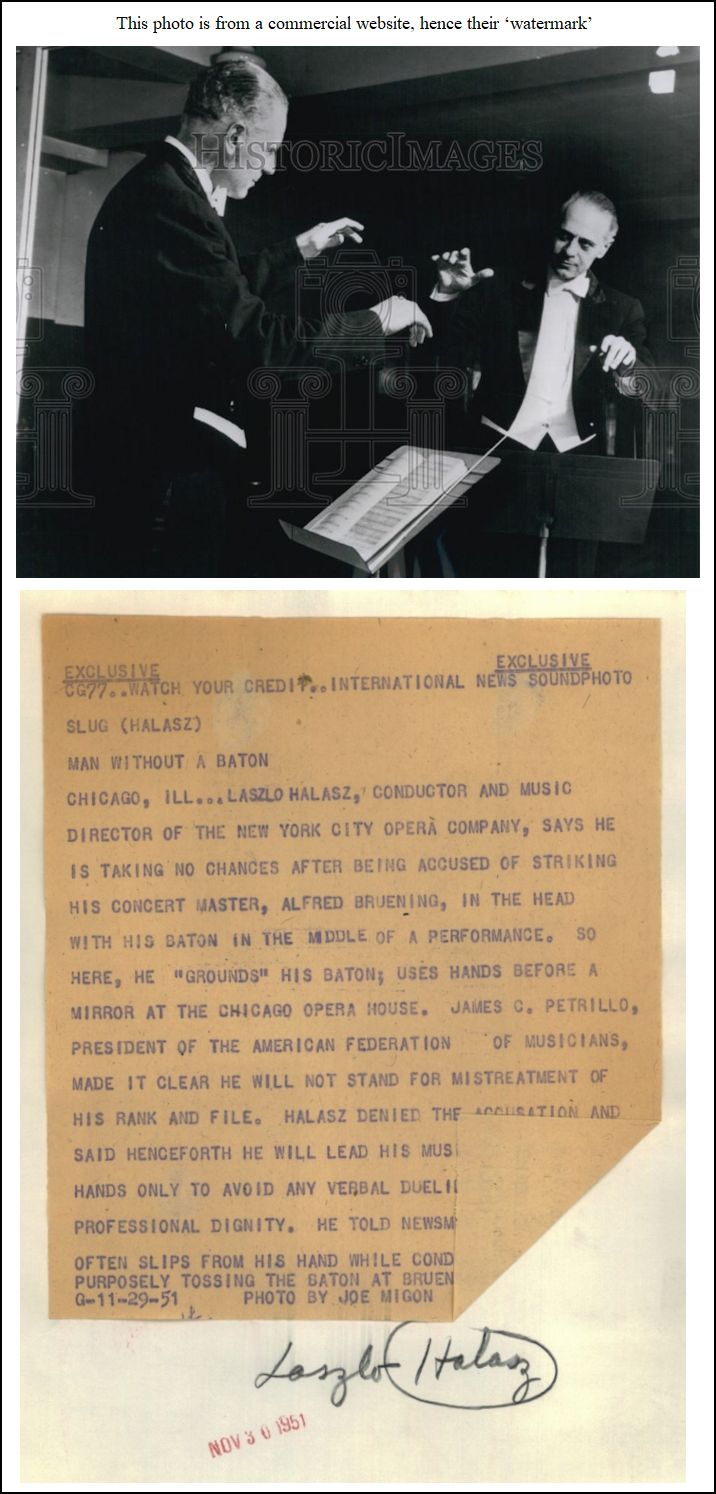

| James Caesar

Petrillo and (March 16, 1892 – October 23, 1984) was the leader

of the American Federation of Musicians, a trade union of professional

musicians in the United States and Canada. Petrillo was born in Chicago, Illinois. Though, in his youth, he played the trumpet, he finally made a career out of organizing musicians into the union starting in 1919. Petrillo became president of the Chicago Local 10 of the musician's

union in 1922, and was president of the American Federation of Musicians

from 1940 to 1958. The round-faced, bespectacled man dominated the union

with absolute authority. His most famous actions were banning all commercial

recordings by union members from 1942–1944 and again in 1948 to pressure

record companies to give better royalty deals to musicians.

|

RIAS (German: Rundfunk im amerikanischen Sektor; English: Radio in the American Sector) was a radio and

television station in the American Sector of Berlin during the Cold

War. It was founded by the US occupational authorities after World War

II in 1946 to provide the German population in and around Berlin with

news and political reporting. By the end of 1945 the US military administration in Allied-occupied Berlin decided to establish its own broadcasting system, after the Soviets had refused to provide air time on the Berliner Rundfunk radio station. Supervised by the US Information Control Division, broadcasting commenced on 7 February 1946. For the first months the program could be distributed via telephone line only (as DIAS – Drahtfunk im amerikanischen Sektor), until a first medium wave transmitter was installed in September. By its creative and innovative programming, the station quickly gained much popularity. Its importance was magnified during the Berlin Blockade in 1948/49, when it carried the message of Allied determination to resist Soviet intimidation. At the same time, the RIAS Symphony Orchestra under chief conductor Ferenc Fricsay (still existing as the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin) and a professional chamber choir, the Rundfunkchor des RIAS (present-day RIAS Kammerchor) were also established by the US forces. Together with the RIAS Dance Orchestra and the RIAS Big Band, they largely contributed to the station's entertainment program under the editorship of the former Berliner Rundfunk employee Hans Rosenthal. After the Berlin blockade, RIAS (by now carried on terrestrial medium wave and later FM transmitters) evolved into a surrogate home service for East Germans, as it broadcast news, commentary, and cultural programs that were unavailable in the controlled media of the German Democratic Republic. By its own account "a free voice of the free world", the station aired the chime of the Freedom Bell each Sunday at noon, followed by an excerpt from the text of the "Declaration of Freedom". Listening to it in Soviet-controlled East Germany was discouraged. After the workers' riots in East Germany in 1953, which were the end result of the government's raising of food prices and factory production quotas, the Communist government blamed the incident on RIAS and the CIA.Eventually RIAS was jointly funded and managed by the United States and West Germany. Under the supervision of the United States Information Agency from 1965, the station was staffed almost entirely with German employees, who worked under a small American management team, and broadcast programs for specific groups in East Germany, such as youths, women, farmers, even border guards. RIAS had a huge audience in East Germany and was the most popular foreign radio service. This audience began to shrink only when West German television became widely available to viewers in East Germany. |

|

|

|

V-Disc ("V" for Victory) was a record label that was formed in 1943 to provide records for U.S. military personnel. The label was a morale-boosting initiative involving the production of recordings during World War II by arrangement between the U.S. government and record companies. Many popular singers, big bands, and orchestras recorded V-discs. The name referred to both the label and the discs, which were 12-inch vinyl 78s produced from October 1943 to May 1949. The V-Disc project began in June 1941, six months before the United States' involvement in World War II, when Captain Howard Bronson was assigned to the Army's Recreation and Welfare Section as a musical advisor. Bronson suggested the troops might appreciate a series of records featuring military band music, inspirational records that could motivate soldiers and improve morale. By 1942, the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS) sent 16-inch, 33-rpm vinyl transcription discs to the troops from concerts, recitals, radio broadcasts, film soundtracks, special recording sessions, and previously issued commercial records. Under the leadership of James Caesar Petrillo, the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) was involved in the 1942–44 musicians' strike in which there was a recording ban on four companies. On October 27, 1943 George Robert Vincent convinced Petrillo to allow the union's musicians to make records for the military as long as the discs were not sold and the masters were disposed of. Musicians who had contracts with different record labels were now able to record together for this nonprofit enterprise. The program started for the Army, but soon music was provided for the Navy and Marines. The V-Discs were a hit. Soldiers who were tired of hearing the same

old records were treated to new and special releases from the top musical

performers of the day. The selection included big band hits, some swing

music, classical performances from symphony orchestras, jazz, and military

marches. Radio networks sent airchecks and live feeds to V-Disc headquarters

in New York. Movie studios sent rehearsal feeds from the latest Hollywood

motion pictures to V-Disc. Musicians gathered at V-Disc recording sessions

in New York City and Los Angeles. V-Discs were pressed by labels such

as RCA Victor and Columbia. The V-Disc program ended in 1949. Audio masters and stampers were destroyed. Leftover V-Discs at bases and on ships were discarded. On some occasions, the FBI and the Provost Marshal's Office confiscated and destroyed V-Discs that servicemen had smuggled home. An employee at a Los Angeles record company served a prison sentence for the illegal possession of over 2500 V-Discs. The Library of Congress has a complete set of V-Discs, and the National Archives did save some of the metal stampers. |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on November 28, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, and 1995. This transcription was made early in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.