by Bruce Duffie

TC: Actually, I got my first exposure

to opera from my brother. They were closing down a high school in

our neighborhood and they were giving away records. They gave him

bunches of opera records and those were about the only records we had

in the house. So I listened to them and fell in love with

them. Right away I liked the music. I was about 12 years

old then, so the odds against liking it are 1,000 to 1. But I

started studying a lot of things – like science and math. Right

after I graduated from high school, I decided that I wanted to be a

recording engineer because I loved listening to the music. I

didn’t think I had much chance to make music, and I thought that

because I was black they wouldn’t hire me as a singer. But in

college, while majoring in engineering, I also took voice because I

liked singing. I sang in the chorus.

TC: Actually, I got my first exposure

to opera from my brother. They were closing down a high school in

our neighborhood and they were giving away records. They gave him

bunches of opera records and those were about the only records we had

in the house. So I listened to them and fell in love with

them. Right away I liked the music. I was about 12 years

old then, so the odds against liking it are 1,000 to 1. But I

started studying a lot of things – like science and math. Right

after I graduated from high school, I decided that I wanted to be a

recording engineer because I loved listening to the music. I

didn’t think I had much chance to make music, and I thought that

because I was black they wouldn’t hire me as a singer. But in

college, while majoring in engineering, I also took voice because I

liked singing. I sang in the chorus.|

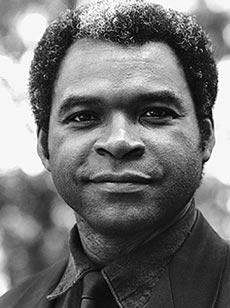

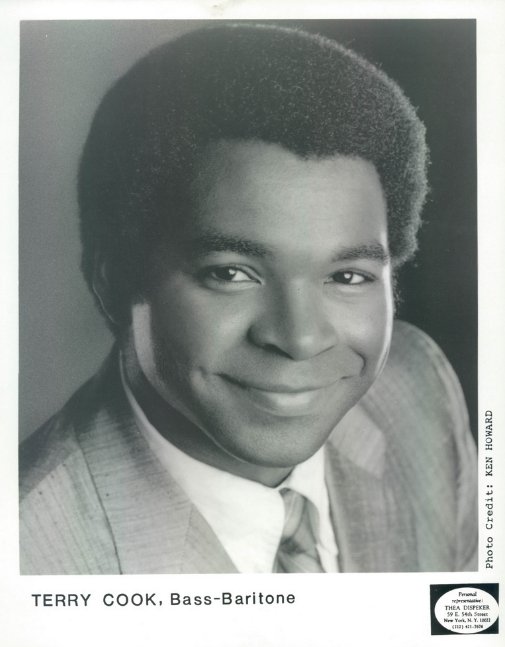

Bass Terry Cook has appeared with most of the major opera companies and symphony orchestras around the world. He’s known especially for his portrayal of the title role in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. He took part in New York Harlem Productions’ Porgy and Bess in Germany, Norway, Spain and Italy, with the Houston Grand Opera at Opera Bastille and at La Scala, as well as at the Bregenzer Festspiele and in a new production at the Treatro Real in Madrid. Mr. Cook has sung in over twenty productions at the Metropolitan Opera, most recently in La Gioconda, La Fanciulla del West (new production), II Trovatore, Un Ballo in Maschera (telecast on PBS' "Live from the Met") and Les Troyens. Other productions included La Traviata, Billy Budd, ldomeneo, Simone Boccanegra, Samson et Dalila, Aida, Tannhäuser, La Clemenza di Tito, Giulio Cesare, Salome, Porgy and Bess, Semiramide and Parsifal. The 2009/10 season brought his signature portrayal of Crown in Porgy and Bess to the Washington National Opera. He also sang Banquo in Macbeth at the Fresno Grand Opera and appeared with the Atlanta Symphony. In 2008/09 he reprised the role of Crown at the Lyric Opera of Chicago and during 07/08 he sang the title role in Rise for Freedom: The John P. Parker Story (premiere) with Cincinnati Opera, as well as Crown with both National Philharmonic and Fresno Grand Opera. In season 2006/07, Mr. Cook performed the role of Zuane in La Gioconda with the Metropolitan Opera, as Crown in Porgy and Bess with Los Angeles Opera, in a workshop of Hailstork’s We Rise for Freedom: The John P. Parker Story with Cincinnati Opera and Christmas Oratorio with Xalapa Symphony in Mexico. In the Fall of 2005, Mr. Cook sang the role of Crown in Porgy and Bess with the Washington National Opera. In the summer of 2006, he sang Osmin in Mozart’s Zaide, a new, joint production of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York, Barbican Centre, London, and Wiener Festwochen, Vienna, directed by Peter Sellars and conducted by Louis Langrée. Orchestral engagements have included the New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, National Symphony Orchestra, St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Atlanta, Seattle, Detroit, Baltimore and Houston Symphonies. Mr. Cook has performed under such esteemed conductors as James Levine, Charles Dutoit, Seiji Ozawa, Erich Leinsdorf, Robert Shaw, Sir Simon Rattle, Pinchas Zukerman, Trevor Pinnock, Sir Colin Davis, Christopher Hogwood, Vladimir Ashkenazy and Gerard Schwarz. Terry Cook's recordings include

Beethoven's Choral Fantasy with the Cleveland Orchestra under

Vladimir Ashkenazy on London Records and Aida with James Levine

for Sony Classical. --

Agent biography, September, 2011 |

This interview was recorded in a dressing room

backstage at the Civic Opera House in Chicago on November 24,

1982. It was transcribed

and published in The Opera Journal

in December, 1985. It was slightly re-edited and posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.