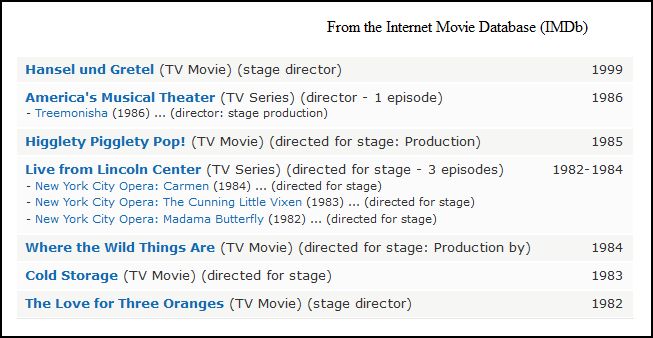

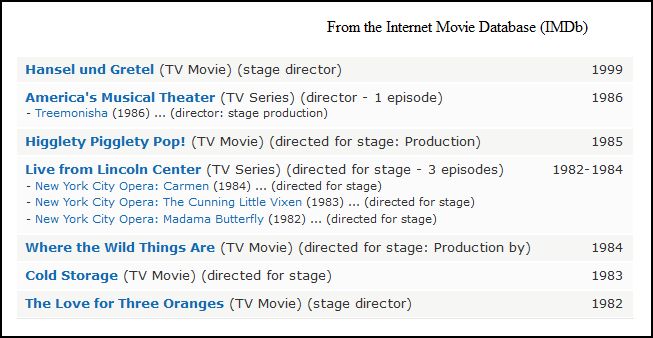

This interview was held in December of

1988, and published in The Opera Journal two years later. It

has been slightly re-edited, and the photos and links (which refer to my

interviews elsewhere on my website) have been added for this website presentation.

Conversation Piece:

Director Frank Corsaro

By Bruce Duffie

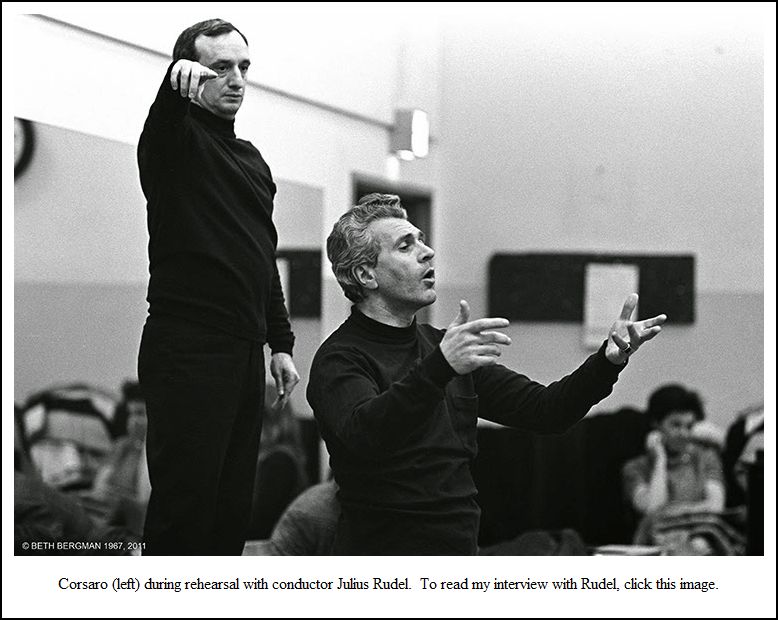

One of the major figures in American stage-direction these days is Frank

Corsaro. A native New Yorker, he graduated from the Drama School

of Yale University, and has directed plays, musicals, and operas across

the United States. He appeared on Broadway with Helen Hayes, an in

a film with Paul Newman. Always an innovator, Corsaro has breathed

new life into many works, and continues to make audiences think about the

production before them.

It was in Chicago a couple of seasons ago that Corsaro took time before

the premiere of Oliver

Knussen’s Where the Wild Things Are to chat with me about his

ideas, both general and specific. Unassuming and rather down-to-earth,

he never lets you forget that he has ideas and directions, and is willing

to stick his neck out when he thinks it will make those concepts clearer to

both performer and audience.

To celebrate his sixty-fifth birthday, I am pleased to share with members

of the national Opera Association the hour we spent together. While

setting up for the conversation, he asked me about working at the radio

station — WNIB,

Classical 97 in Chicago. We had moved ahead of the other classical

station in the ratings, and I commented that we were quite proud of what

we had accomplished. We pick up the thread right there . . . . . .

.

Bruce Duffie: Are you proud of what you do?

Frank Corsaro: Not all the time. You don’t usually

have the kind of circumstances that are propitious in many instances.

It’s very difficult to put things together.

BD: So how do you overcome the difficulties of

circumstance or cast?

FC: You make do with what you have, of course,

or make whatever changes are necessary if you have the time. Otherwise,

you suffer through it, and hope the next will be better. I’m curtailing

a lot of my activity now because I’m the artistic director of The Actors

Studio. That’s an old acquaintance of mine, and also I’ll be involved

in heading the American Opera Center at Juilliard. So, I’ll be able

to do with young people the kind of work that I’d love to do anywhere, but

time and circumstances don’t allow. I’ll do some work outside, but

these two ventures will provide a nice amalgam for me. I’m grateful

that I don’t have to be the Willie Loman of opera — pick

up my bag and schlep to the next town! [Both laugh]

BD: Are you optimistic about the whole future of

opera?

FC: That’s very difficult to say. I’m very

concerned that in most of the major opera houses in this country we seem

to need confirmation from Europe. We still are very much concerned

about an image that can only be given to us by foreign involvement.

The constant bringing-in of foreign singers who, most of the time

— at least at the Metropolitan Opera if you read the papers

— are way under par. This is against American singers

who are on the rise, and are quite wonderful, and will hopefully simply

overcome the opposition. I include directors in this. Foreign

directors are given preference over Americans who need the opportunity.

The general atmosphere is that European singers, directors, and conductors

know better than we what we’re about, and that they have the style.

I don’t believe all that for one minute.

BD: Then let’s cut through all of this. Who

are we, and what is opera about?

FC: It’s a combination of declension, and the time

in which the director has come forward in interesting ways. There

are many new and unusual approaches to music from conductors, so my feeling

is that as the new begins to wash away the old remains, America may finally

accept that it has a lot to say — if not more

to say than they realize — about the best.

They will stop turning rocks over in the depths of Europe, searching for

people with longer names.

BD: Is there ever a case where the director has too much

power in the opera house?

BD: Is there ever a case where the director has too much

power in the opera house?

FC: I don’t know of one. What does that mean

— too much power?

BD: Taking too much upon himself and ignoring musical

values.

FC: Oh, well, you have a variety of directors now

who all swear they pay attention to the music, and sometimes you wish they

didn’t and really did what they set out to do, which is to really prove

the point. I don’t really know of any director who is so omnipotent

that his word goes beyond anyone else’s. In the really good cases

— or the cases one enjoys and feels a new experience

— the director does seem to know more about the nature of

what they’re doing. I’ve found that to be true eighty per cent of

the time.

BD: Do they know more than the composer?

FC: My answer to that is simple. You can’t

second-guess a dead man, and don’t try. That’s all we’re doing.

I’m so sick and tired of those who supposedly ‘know what was intended’.

I learned that lesson when I had two Italian conductors, both of whom professed

to have learned the score of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut at his knee.

They were alternating in the pit, and had diametrically opposed points

of views. [Laughs] They were obviously of either knee, and

one had gout or something!

BD: Then is it easier for you, as the director,

to work with a living composer?

FC: Yes, as a matter of fact, but the living conductor

gives me a good indication of what the dead composer must have been like.

You constantly read about composers obliging this or that star. Handel

was almost apoplectic about that, but he did do it. Sometimes he

got good results, which proves that getting a good performance is very much

dependent on the occasion, and things are rapidly changed when they need

to be changed. Composers, like playwrights, don’t always know about

what it is they actually have in hand. They have a certain idea, but

in actual performance things change. That is the nature of the beast,

and that includes opera, and I don’t care which name you invoke.

BD: Are those changes always for the better?

FC: Who knows? That’s part of our problem

— we’re constantly trying to ameliorate. We’re always

trying to re-assess, to re-consider, to re-interpret. I don’t think

that there is as much re-approximation, or re-appraisal and re-hauling

in the theater as there is in music. That says something.

BD: So, here’s the Capriccio question.

In opera, where is the balance between the music and the drama?

FC: They’re interlocked, interlinked, and inter-everything!

I don’t think you can say one is stronger than the other because one provokes

the other. The composer could not have done anything without the

words. In the long run, the music, of course, becomes the living

style of the piece, but you have to pay attention and realize that it is

in the linkage that makes for the balance. Very often, the music is

doing something other than what the words are saying, so you have to really

pay close attention to that division. Many people don’t realize the

separateness of them, even as they are linked together.

BD: Is that what makes a great opera

— where they are linked closer?

FC: No, not necessarily. The old boys

— the really good ones — knew

what they were doing. Characters can be lying in their words, and

there can be turbulence in the orchestra during an otherwise sad or mournful

scene.

BD: If there is turbulence in the orchestra, do

you also have to put turbulence on the stage?

FC: It depends. That’s the wonderful business

of directing — how do you make the scene come

to life? How do you interpret that? It depends on the director’s

imagination, and the ability to seize on the sensibility of the given moment

and dramatize it with as much imagination and fidelity to the idea.

Too many directors nowadays exploit the music. In reality, if they

were to face the fact, they are not doing their job. Essentially, when

you really interpret a piece, music and lyrics work together so there is

a harmonious sense in choices of tempi, the way phrases are made, the whole

sense of the living experience. I’ve found that a parallel set of

tracks are going on — a straight, ‘correct’ rendering

of the music, and behind it is this ghastly psychoanalysis which tweaks

the variety of shapes and forms describing what really should be there

— and never the twain shall meet. It’s a fake modernization.

Even in the theater, if you take Shakespeare or any of the classics, the

words have their own meter and their own time. But there are all sorts

of elements involved that are extraordinary. In a funny way, if something

is working, and is really good and really valid, it can clean a tarnished

masterpiece. The dust and soot have accumulated by sheer dint of time.

BD: So you want each audience to experience it

as though they’ve never seen that work before?

FC: That’s what the idea is supposed to be.

That’s what you go to the theater for. You go to experience something

for the first time. In a well-known work, you can get this feeling

by nature of the people you’re doing it with. Because of who they are,

they will have to bring something of their own. If they don’t, they’re

not doing their job and not serving the composer. You serve him

by recreating the instinct and the impulse, and making it a fresh experience.

If it isn’t fresh, it’s not only boring, but you begin to wonder why you’re

about to fall asleep even though the work is a masterpiece. It proves

that what happens onstage is very important to the musical effect, otherwise

you’re just listening to a recording.

BD: Do commercial recordings interest you since

there is no visual drama?

FC: The good ones do. Most of the ones now

are just dreadful — homogenized junk food of

the contrivances. Ones that come from live performances, or have

a sense that a conductor can really grasp a piece and give you a fresh sense

of it are a rare exception. The older ones seem to have that.

There was always a sense of accumulated value.

BD: Is that because the older recordings utilized

singers who had done the roles onstage and become noted for them?

FC: Most of the singers recording now have experience

onstage, perhaps even more so than before. The singers today zip

around the world. It’s the lack of initiative on somebody’s part in

not centralizing any given opera production so it appears as a very individual

statement. I did Alcina in London and then in Los Angeles.

I approached it with a kind of magical realism. Handel is very dramatic,

and we worked hard, and arrived at a very dramatic sense of the piece.

Then came the recording, and I invoked the gods, pleading that they would

not do it any differently. I wasn’t asked to be there for the recording

sessions, but the conductor simply wiped it all out, and so what you hear

on the discs, with Arleen

Auger, is this strangely not-quite-committed sense of what is it. Finally,

somewhere along the line it did pick up, but I felt it was an actual crime,

and if I ever meet the conductor again I’m going to let him have it!

He didn’t realize that this was the very thing which was making the performance

exciting and really individual. It is fresh and new for singers to

do that, and they needed to continue it in the recording studio. Maintaining

that level, whatever it is, is a tricky problem, and requires everyone

working together to do it.

BD: So, how do you maintain that level during a

string of performances?

FC: In that sense, they are still working within

the given requirements. But take them into the studio where there

is no action and no scenery, and it’s a new thing completely.

BD: Do you foresee a time when record companies

will hire a stage producer for a purely aural recording?

FC: I’ve hear that a famous director was hired

to do the recitatives in the Don Giovanni conducted by Haitink. I think

that is a very good idea, but conductors are very afraid of that kind of

thing in recording. It’s like those awful recordings where actors

spoke the dialogue for the singers. It’s a tricky balance, but it

has to do with a way of going, and that’s our problem. We don’t really

have a way of going. It’s haphazard rather than maintaining standards.

BD: In Europe, each opera house has a Dramaturg.

Should we have that kind of thing in America?

FC: Absolutely! We should have people who

watch out for that, who maintain an artistic equilibrium.

* * *

* *

BD: Let us go one step further. Do you like

opera on television?

FC: Some of it... too little of it, really.

I’ve had a lot of my productions done on TV, and some I’ve been involved

in making sure that the camera caught what I had in mind. You have

to work with the TV director, and when you don’t, it’s mayhem. I’ve

seen that too often. I’ve seen a TV man direct with his nose in the

score and not really pay attention to what was going on on the stage.

But when it’s good, it can be quite enlivening. There is an air of

mythical reality about it that is quite wonderful, but most of the time

we’re watching magnifications of absolute mediocrity. You couldn’t

even get away with it in a bad film. It would be handled better.

My problem with the ‘Live from the Met’ productions is that they’re so dead!

There’s nothing going on there. They’re photographing a star singer,

but that’s what they sell. On the other hand, films of operas have

the problem of the sound track. The picture can have the artist here

or there, near or far, and the voice is always the same. Nothing changes.

A brick falls and hits them on the head, and it’s still the same sound.

BD: I would think it could be simple to record

on twenty-four tracks, isolate each principal singer, and then pan them

around the scene as needed.

FC: Absolutely, but all of those things are arranged

economically. The recording and the picture are all in a tight package.

I’d be happy to strangle somebody or head up an assassination squad to get

things put right. I really must confess that the best I’ve ever seen

has been in Europe — Walter Felsenstein in East

Berlin, Harry Kupfer, people like that.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You mean that the

best opera you’ve ever seen was not a Frank Corsaro production???

FC: No, no, no! I have to work in such a

rapid manner. I’ve done some good stuff, and some bad, but in this

country I represent a pretty high level of work. I’m trying desperately

to get more theater people involved.

BD: How much is sheer time?

FC: It’s not so much the lack of time, strangely enough.

Often, it’s just the lack of musical background. A lot of the

young directors just don’t have that background. They’ll go to the

libretto rather than the score to study.

BD: What advice do you have for a young person

who wants to direct opera?

FC: I have no one bit of advice. Usually,

if they’re interested, they come forward. It’s a question of reinvigorating

education. We are working on creating a liaison between the New

York City Opera and Juilliard, which would be marvelous, but most opera

houses have to beg indulgence of Mme. X and Sig. Z. It’s murderous.

Managements are helpless today because they’re all scrambling for the superstars

and their time.

BD: Then what hope is there for the student at

Juilliard who goes through your program and then is out in the real world?

FC: There’s every great hope, especially because they

will be much better armed. The Europeans have a very lopsided view

of what technique in opera performance is all about. Some have voices,

some can act, but there is never a sense of what they can do in terms of

the entire level of the talent. So, you compensate for people who

are not capable — even over a long period of time

— of being able to execute anything that is helpful in

creating an actual experience... except for simply singing. There’s

a wonderful book on opera by Stanislavski [(1863-1938), founder of the

Moscow Art Theater in 1898, the Opera Studio in 1918, and the Opera-Dramatic

Studio in 1935]. I’m not for cup-and-saucer opera, but a personality

like Chaliapin embodied the best of both — the

overwhelming star with enormous flair and theatricality.

BD: How much work do you expect on the part of

the public each night?

FC: A lot. The only way to be entertained in

the theater is what I’m describing, otherwise you get the same old hamburger

each night, the same popcorn, the same old movie.

BD: The same Pavarotti high C?

FC: Who cares? That’s silly. I really

think it’s silly that we depend on that as representative of going to the

opera. When he loses his high C, he’s no good, and that’s crazy!

One of my first great lessons in opera was in Lucia with Callas at

the Met. In the Sextet, everyone turned front to sing except

her. She stayed in the corner doing what she was doing, and everyone

in the audience looked at her. Something was happening. I realized

that this was what all these sextets and quintets were about

— people talking to themselves, not all out front to the

audience. At the end, she didn’t hit the high E, and people were upset,

but she created a spellbinding performance. That shows you what crude

bastards most audiences are. The theater audiences are infinitely

more sophisticated. The opera audiences are, I feel, nouveau riche

culturally. They’ve been listening to records, and have been sold

Pavarotti on television. They’re media-influenced. A foreign

name in a well-known opera makes a special occasion. Those are possible

ingredients, but when you get there, it fizzes away.

BD: So why do you direct opera and not stay in

the straight theater all the time?

FC: Because I think that when opera is at its best,

it’s really better than any straight theater I know. I’ve had some

really great experiences in opera and continue to have them, but unless

you have people like myself who keep yelling and screaming and pushing

managers, they may as well give up and turn it over to the slaves and lackeys

who put it all together. The director is very new in opera.

He’s hardly thirty years old. Before, it would be the composer or

the publisher.

BD: Let’s open another can of worms. What about

translations and supertitles?

FC: I have nothing against them. Obviously,

if they’re good, fine. I’m doing the Andrew Porter translation

of The Magic Flute, and he keeps working on it, whittling away

and changing. I have nothing against supertitles. Anything

that helps the audience is fine with me. As a matter of fact, when

it’s difficult to get the English words, you should use supertitles there,

too. We did The Cunning Little Vixen for television in English,

and I said to put the titles on anyway. They did, and it was very

helpful. It’s simple enough not to look at them if you know what’s

going on. Particularly for a new opera, they’re very important.

BD: Going to comedy, how do you keep it from becoming

slapstick?

FC: I always try to elucidate it. The Marriage

of Figaro is always silly putty. People are behaving badly in

that as in a broad farce, but it’s a lack of resource. We need people

who really know how to live on stage, really know how to project thought,

how to permit that to happen, and how to direct that. It is what

Stanislavski was trying to say in his book. I try very hard for that.

When theater-practice becomes opera-practice, there will be a wonderful

balance. The unfortunate thing now is that they try to over-demonstrate

the director’s vision, and don’t sufficiently make the people real people,

rather than director’s intents. In that respect, the director doesn’t

help. Also, it is a lack of training. A lot of the people aren’t

trained in the process of singing, to trust themselves, their own thoughts,

their own contributions. They’re always being told in music what

to think, how the style goes, what is correct, and I think that’s a crock.

Individuality is stymied in this profession.

BD: So, the singers should learn the basics, and

then trust themselves?

FC: Yes. I’ve been teaching that for a while

now, and getting wonderful results. They should always find out

what they are there onstage — why

are they singing this music, what is it that they contribute to this music

that makes it worthwhile for us to want to hear them, what it is that they

will do that will be so special that they will illuminate that piece of

music.

========

========

========

---- ---- ----

======== ========

========

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 17, 1988.

The transcription was made and published in The Opera Journal in

December, 1990. It was slightly re-edited and posted on this

website in 2018. My thanks to British soprano

Una Barry for her

help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with

WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment

as a classical station in February of 2001. His

interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals

since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are

invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including

selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full

list of his guests. He would also like to call your

attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

BD: Is there ever a case where the director has too much

power in the opera house?

BD: Is there ever a case where the director has too much

power in the opera house?