A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

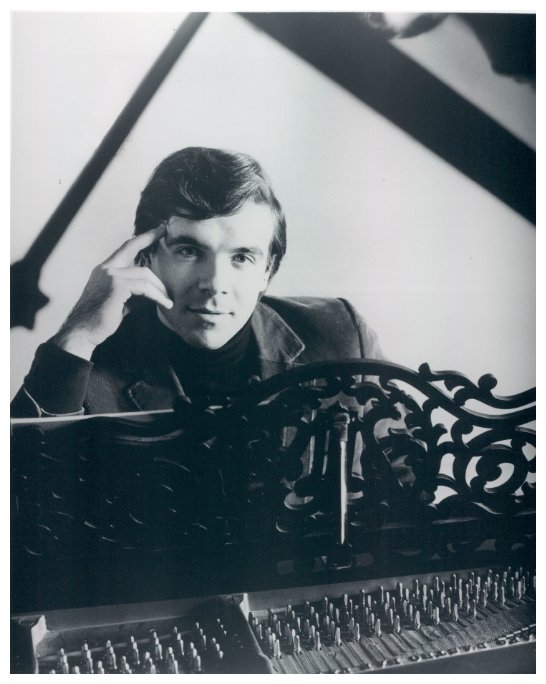

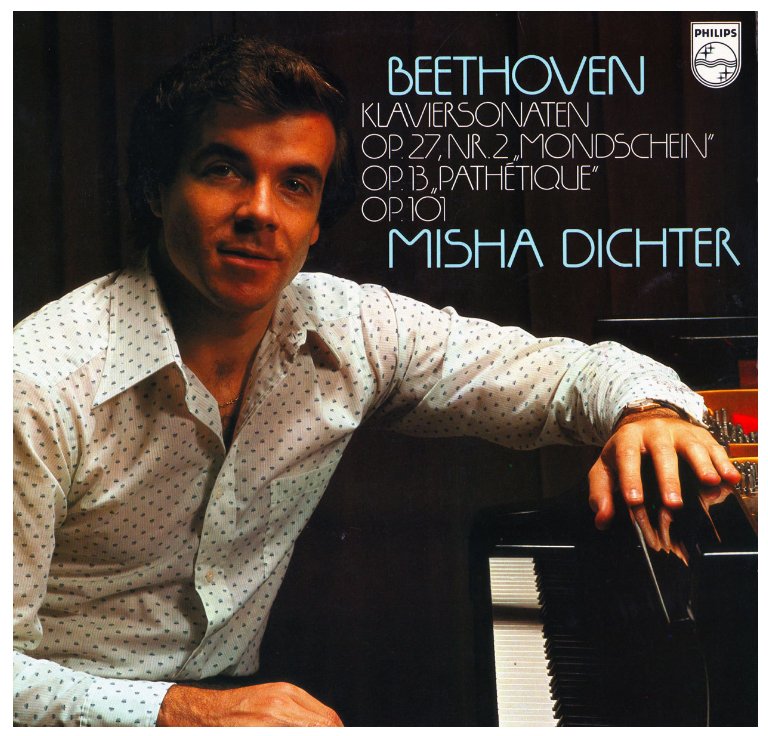

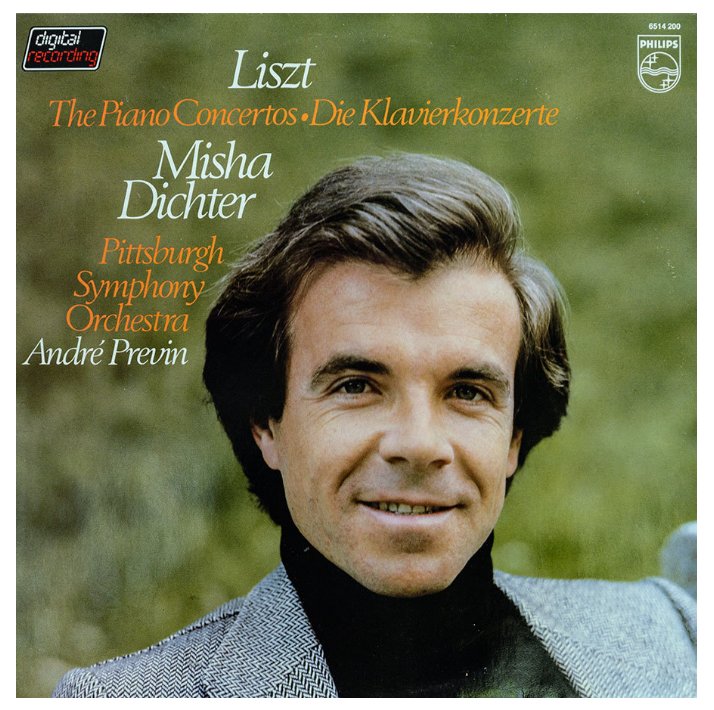

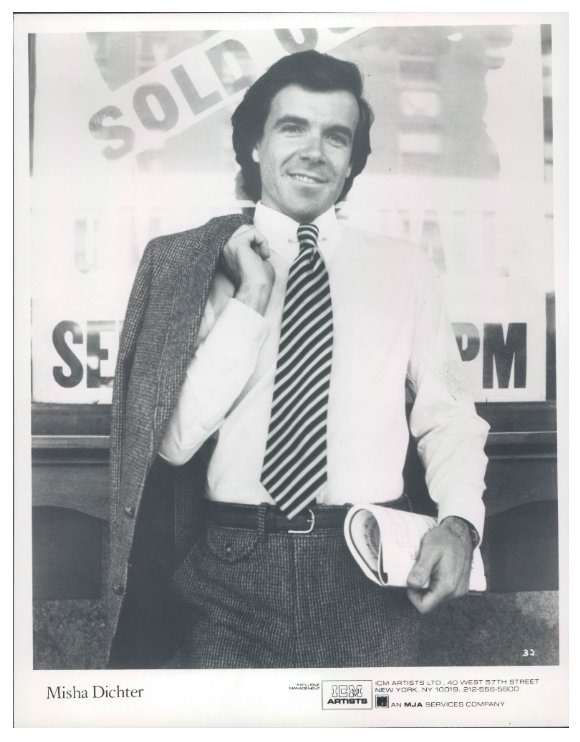

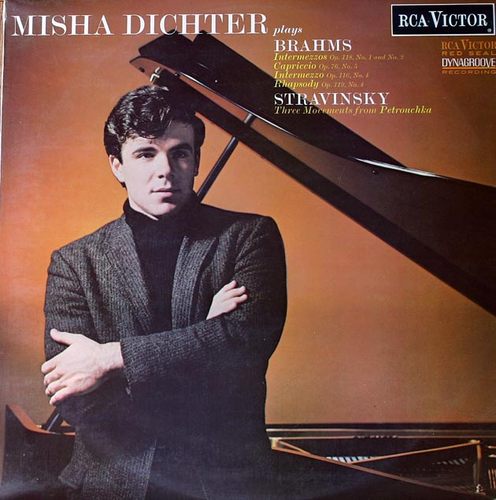

| Misha Dichter was born in Shanghai

in 1945, his Polish parents having fled Poland at the outbreak of World War

II. He moved with his family to Los Angeles at the age of two and began

piano lessons four years later. In addition to his keyboard studies with Aube

Tzerko, which established the concentrated practice regimen and the intensive

approach to musical analysis that he follows to this day, Mr. Dichter studied

composition and analysis with Leonard Stein, a disciple of Arnold Schoenberg.

He subsequently came to New York to work with Mme. Lhevinne at The Juilliard

School. At the age of 20, while still enrolled at Juilliard, he entered the 1966 Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, where his choice of repertoire—music of Schubert and Beethoven, Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky—reflected the two major influences on his musical development. Mr. Dichter’s stunning triumph at that competition launched his international career. Almost immediately thereafter, he performed Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 at Tanglewood with Erich Leinsdorf and the Boston Symphony, a concert that was nationally broadcast live on NBC and subsequently recorded for RCA. [See Bruce Duffie’s Interviews with Erich Leinsdorf.] In 1968, Mr. Dichter made his debut with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, performing this same concerto. Appearances with leading European ensembles, including the Berlin Philharmonic, Concertgebouw of Amsterdam, and the principal London orchestras, as well as regular performances with major American orchestras, soon followed. An active chamber musician, Mr. Dichter has collaborated with most of the world’s finest string players and frequently performs with Cipa Dichter in duo-piano recitals and concerto performances throughout North America and in Europe, as well as top summer music festivals in the U.S., such as Ravinia, Caramoor, Mostly Mozart, and the Aspen Music Festival. They have brought to the concert stage many previously neglected works of the two-piano and piano-four-hand repertoires, including the world premiere of Robert Starer's Concerto for Two Pianos, the world premiere of the first movement of Shostakovich’s two-piano version of Symphony No. 13 (Babi Yar), and the world premiere of Mendelssohn’s unpublished Songs Without Words, Op. 62 and 67 for piano four hands. Mr. Dichter’s master classes at music festivals and at such conservatories and universities as Juilliard, Curtis, Eastman, Yale, Harvard, and the Amsterdam Conservatory, are widely attended. An accomplished writer, Mr. Dichter has contributed many articles to leading publications, including The New York Times. He has been seen frequently on national television and was the subject of an hour-long European television documentary. Mr. Dichter is also an avid tennis player and jogger, as well as a talented sketch artist. His drawings, which have served as a sort of visual diary, have been exhibited in New York art galleries. Mr. Dichter lives with his wife, pianist Cipa Dichter, in New York City. They have two grown sons. |

MD: I consider everything wonderful and worthwhile,

and it’s just a question of having enough time, which I just don’t.

We always stay with friends in Chicago, and his piano in the living room has

various volumes of the Complete Whoever. I start reading through things

and I almost forget that I have a concert that night of things that I know

very well, because I think of what I haven’t learned yet. It just is

astounding how much we have to learn.

MD: I consider everything wonderful and worthwhile,

and it’s just a question of having enough time, which I just don’t.

We always stay with friends in Chicago, and his piano in the living room has

various volumes of the Complete Whoever. I start reading through things

and I almost forget that I have a concert that night of things that I know

very well, because I think of what I haven’t learned yet. It just is

astounding how much we have to learn. MD: That’s the Starer Double Concerto. Except for the

Mozart double, everything I’ve done with my wife has been with music.

That, in effect, took the curse away from using music as far as I was concerned.

I realized once we started playing two-piano music and four-hand music about

twenty-five years ago, almost all of this music was not memorized so there

was no particular stigma attached to that. It’s perfectly fine to look

at the music like every other musician does.

MD: That’s the Starer Double Concerto. Except for the

Mozart double, everything I’ve done with my wife has been with music.

That, in effect, took the curse away from using music as far as I was concerned.

I realized once we started playing two-piano music and four-hand music about

twenty-five years ago, almost all of this music was not memorized so there

was no particular stigma attached to that. It’s perfectly fine to look

at the music like every other musician does. MD: Never three rehearsals.

MD: Never three rehearsals. BD: Was that appropriate for the Schubert?

BD: Was that appropriate for the Schubert? MD: It’s interesting. I’m an old-timer this

way. I started playing professionally in the mid-sixties, when, in retrospect,

recitals were probably at the tail end of a golden era. Presenters

around the country were slowly closing up shop on recital series, and I saw

the very end of that. I was used to a season of twenty or twenty-five

recitals, starting in September with a brand new program that I had just

learned that summer. I would be going around and by October it began

to feel that it’s shaping up, and by January I was ready for a New York appearance.

This was really working it in the old fashioned way, like trying it out as

a Broadway show somewhere and honing it to perfection, if that’s possible.

In the waning years of that, I’d been complaining to my management that those

days are over, and that kind of work is not possible on that level — the

rethinking every day, playing the same program day after day, thinking about

it again and going to the next city. I haven’t originated this because

I read Eugene Istomin having done this several years ago — traveling

with a couple of pianos around the country doing one-night stands of concerts

and recitals, and every concert being about two hundred miles from the next

one. He had a truck, a sort of U-Haul thing with a Steinway concert

grand or two in the back. A piano of your choice is the most important

thing — not necessarily Chicago and Cincinnati and

Cleveland and Boston and Philadelphia and New York, but a lot of places in

between. I’m going to try that this year for the first time, giving

about twenty-five recitals just that way in between the usual recitals and

orchestral concerts in the larger cities because I want to get back to that.

I don’t want to lose touch with that. Most of my colleagues complain

that a normal recital season now may have five to ten recitals, and that’s

just not the way to get a program going.

MD: It’s interesting. I’m an old-timer this

way. I started playing professionally in the mid-sixties, when, in retrospect,

recitals were probably at the tail end of a golden era. Presenters

around the country were slowly closing up shop on recital series, and I saw

the very end of that. I was used to a season of twenty or twenty-five

recitals, starting in September with a brand new program that I had just

learned that summer. I would be going around and by October it began

to feel that it’s shaping up, and by January I was ready for a New York appearance.

This was really working it in the old fashioned way, like trying it out as

a Broadway show somewhere and honing it to perfection, if that’s possible.

In the waning years of that, I’d been complaining to my management that those

days are over, and that kind of work is not possible on that level — the

rethinking every day, playing the same program day after day, thinking about

it again and going to the next city. I haven’t originated this because

I read Eugene Istomin having done this several years ago — traveling

with a couple of pianos around the country doing one-night stands of concerts

and recitals, and every concert being about two hundred miles from the next

one. He had a truck, a sort of U-Haul thing with a Steinway concert

grand or two in the back. A piano of your choice is the most important

thing — not necessarily Chicago and Cincinnati and

Cleveland and Boston and Philadelphia and New York, but a lot of places in

between. I’m going to try that this year for the first time, giving

about twenty-five recitals just that way in between the usual recitals and

orchestral concerts in the larger cities because I want to get back to that.

I don’t want to lose touch with that. Most of my colleagues complain

that a normal recital season now may have five to ten recitals, and that’s

just not the way to get a program going. BD: Yet, because of the solo repertoire, you can

choose so many different things and be in complete control of what you play.

BD: Yet, because of the solo repertoire, you can

choose so many different things and be in complete control of what you play.This interview was recorded in the office suite, backstage at the

Ravinia Festival in Highland Park, IL on July 22, 1994. Portions

(along with recordings) were used on WNIB later that year and in the following

year, and again in 2000. The transcription was posted on this website

in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.