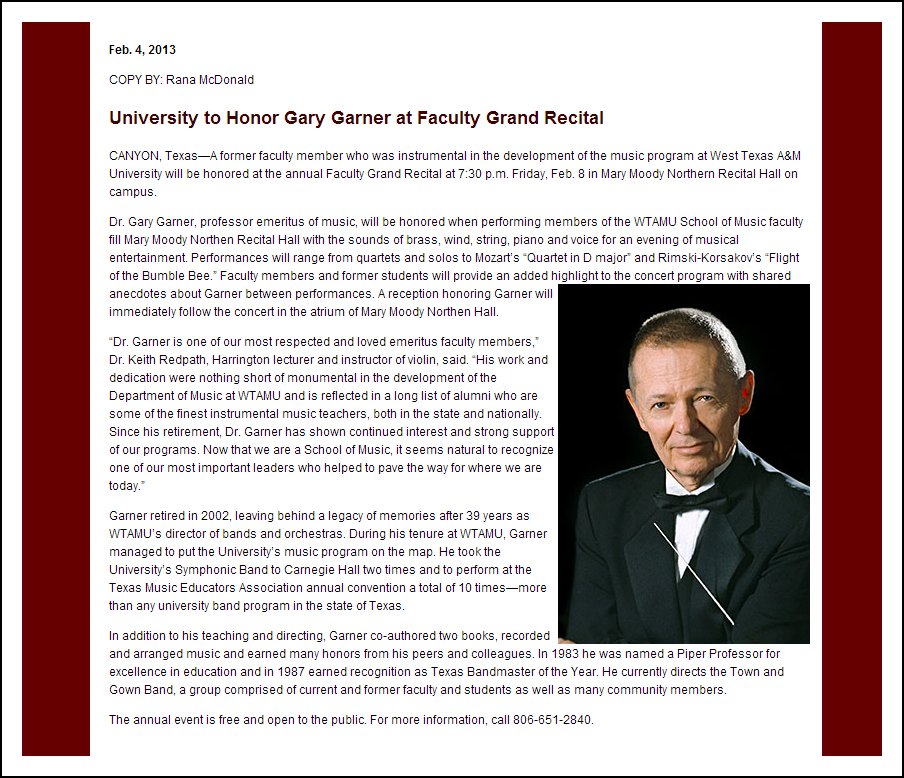

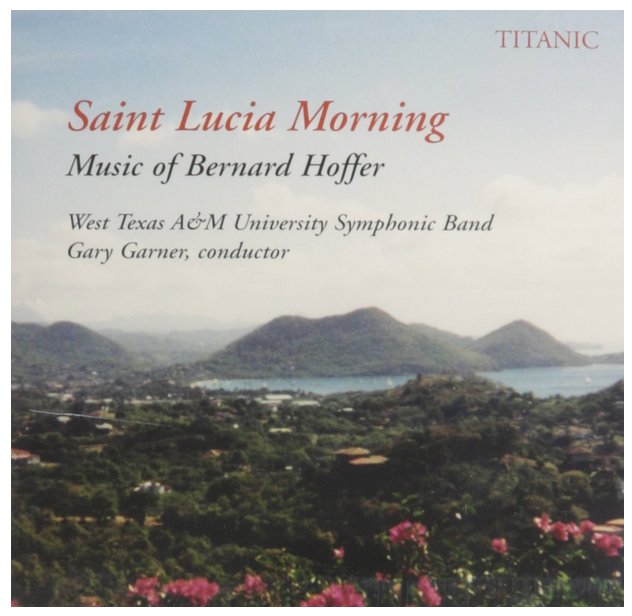

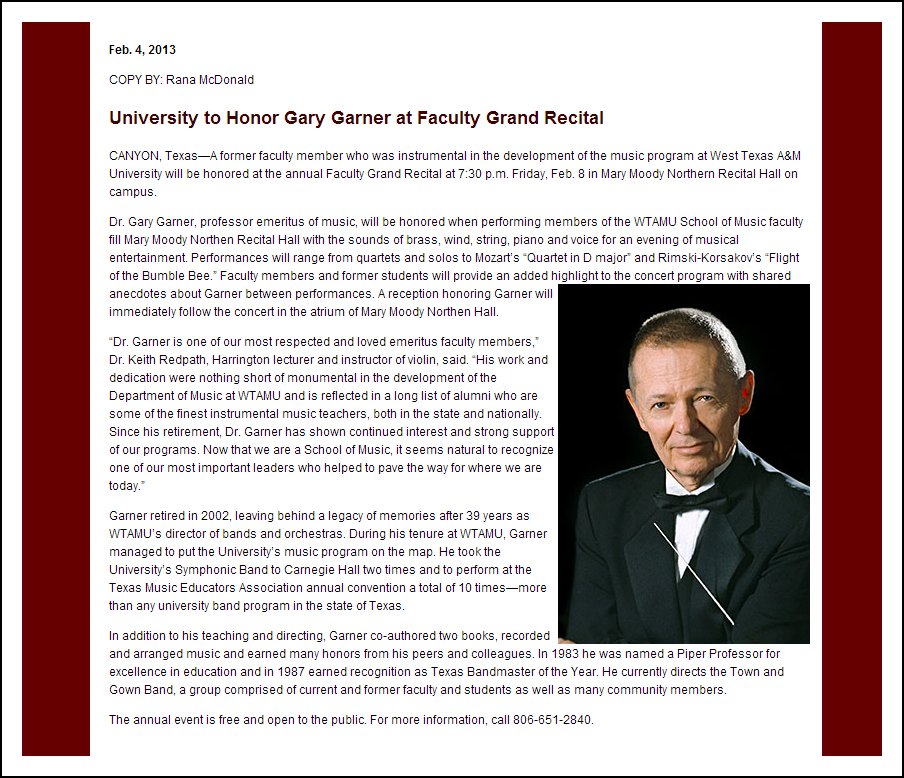

Conductor Gary Garner

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

As this is being typed in July of 2017, I have been in Classical Music

Radio for over forty years. Currently it is just a single program

each week on WNUR-FM, but for just over twenty-five years (1975-2001),

it was my privilege to work full time as an announcer/producer with

WNIB, Classical 97, in Chicago. During that quarter-century I was

able do about 1600 interviews with classical musicians

— composers, conductors, singers, etc., — who came to The

Windy City for performances or other reasons. I also did a few of

these conversations on the telephone with older composers who were not

coming my way, and I gathered a few more on my travels to various

American cities, as well as mainland China! A full list of my

guests is HERE.

In August and September of 2003, my girlfriend, Kathy Cunningham, and I

made an extensive road trip. The first part was a re-creation of

the run made exactly one hundred years previously by my grandfather,

Lawrence Duffie, and others, which established the non-stop record time

of 76 hours in a gasoline automobile from Chicago to New York.

Their exploits in various Columbia Automobiles, which were built in

Hartford, CT, from 1896-1913, are shown on several webpages beginning HERE. The

1903 record is shown HERE.

While we did not adhere exactly to their route, we were told by local

people along the way that many of the roads we used were, indeed,

present one century earlier. We took our time and enjoyed the

trip, rather than try any kind of non-stop race as had been done in the

previous century. I also did a few interviews with musicians

while we were in the New England.

After that, we headed south to visit my father, Burton Duffie (Lawrence’s

son), then almost ninety-six years old, where he was living in a

retirement center in Delray Beach, Florida.

The

next leg of our journey was west, across the deep south to Texas,

to visit Kathy’s

mother in Plainview. It was there that Kathy, a graduate of WT,

and who had played clarinet in Garner’s

ensemble for several years, contacted her former bandmaster and

arranged for this interview before we headed back home to Chicago.

The

next leg of our journey was west, across the deep south to Texas,

to visit Kathy’s

mother in Plainview. It was there that Kathy, a graduate of WT,

and who had played clarinet in Garner’s

ensemble for several years, contacted her former bandmaster and

arranged for this interview before we headed back home to Chicago.

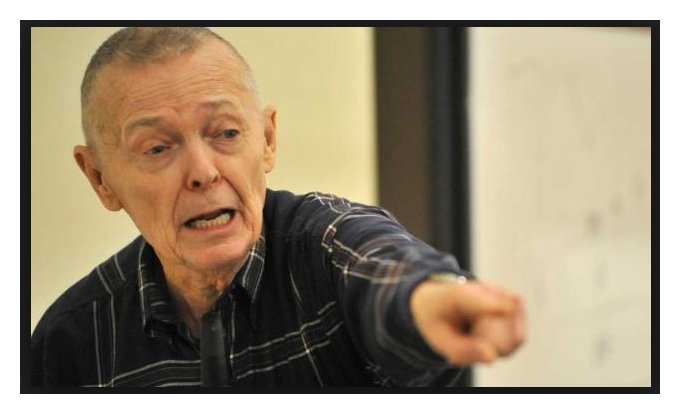

When we arrived at his home in Amarillo, Garner greeted us warmly, and

we settled in for the conversation.

Here is

what was said that afternoon . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: We

will just chat about our favorite

subject. I assume your favorite subject is the same as mine, that

being music?

Gary Garner: You

would be correct.

BD: Is it

wonderful to look back now on a life

immersed in music?

GG: It is indeed,

yes. I wish I could do it all

again.

BD: Would you do

anything different?

GG: As far as

music is

concerned? Yes, I’d learn to play the piano. I’d

have probably studied a little harder as an undergraduate. No, I

would have studied a lot harder! [Both laugh] But my great

regret is that I never did learn to play the

piano. As many do, I had deluded myself into thinking that I was

going to be a band director, so I didn’t need to know how to play the

piano. I even conned the department head into letting me take

French in lieu of piano, which he shouldn’t have done. I thought

he was doing me a great favor, and he thought so

too, but in retrospect I realize that it was not the best of

decisions on my part.

BD: Aside from the

piano, is it safe to assume

that you can get around on all of the other wind, percussion and

stringed instrument to a certain extent?

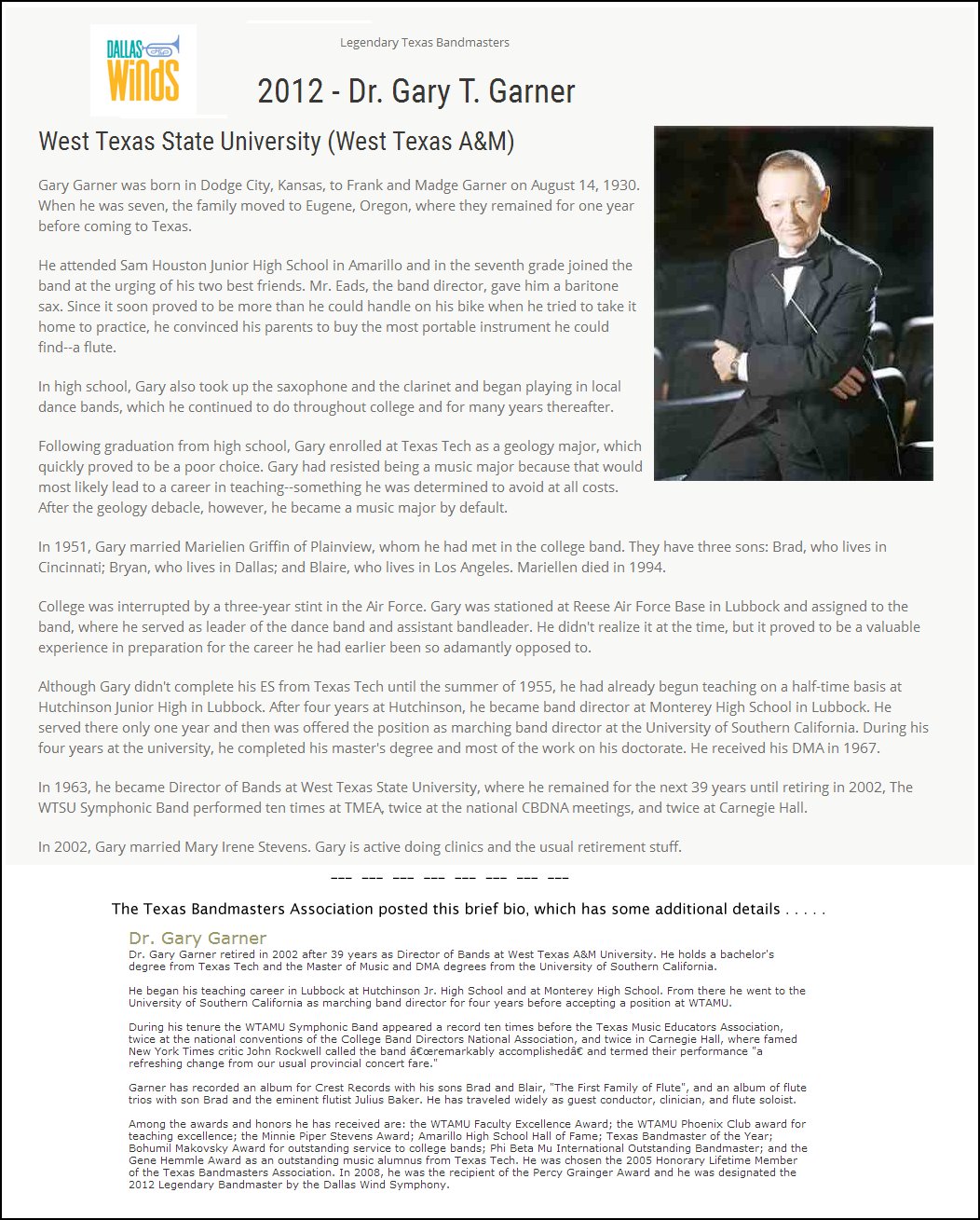

GG: There were

obviously exceptions. Actually I started out as a baritone

saxophone

player. I didn’t intend to get in band at all, and I did it at

the behest of my two best friends who were in the band. I

started late, at the beginning of the school year, and the

only instrument they had left was a baritone sax, which was at least my

size. I had great difficulty in taking it home on my

bicycle. I persuaded my dad I needed a

smaller instrument, and that’s how I became a flute player, which was

the smallest thing I could find. So I began my musical life as a

flute player, and then gravitated in high school to the

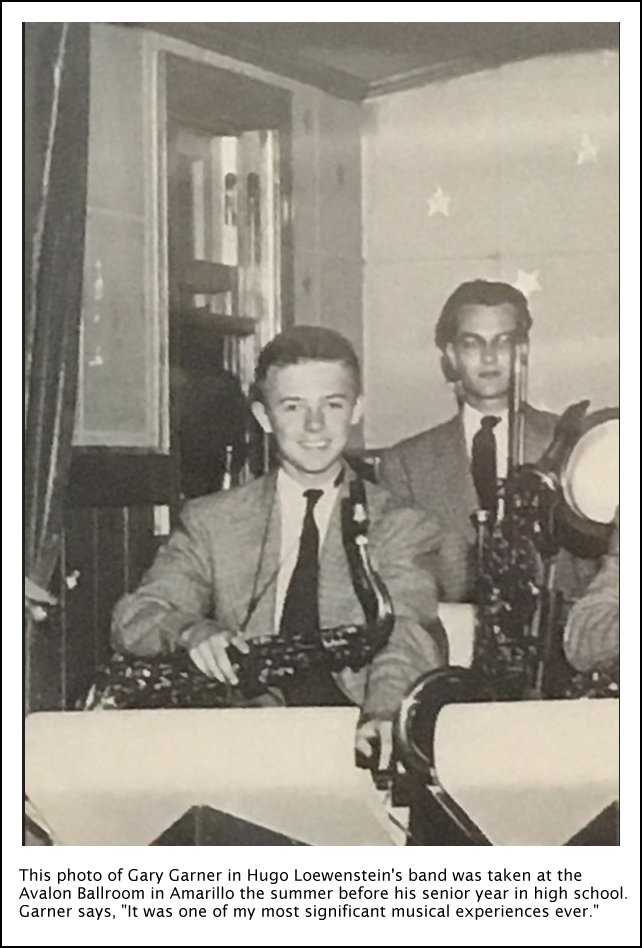

saxophone, and then the clarinet so I could play in dance bands [see photo below].

I did those pretty seriously for a long time, and later on

picked up the oboe and bassoon. When I did a graduate

recital, and was working on a doctorate, I did a woodwind

recital where I played flute, oboe, clarinet, saxophone, bassoon.

I’ve played some trumpet and I can play the other brass instruments,

though I don’t know what I would sound like now. I was always a

poor snare drummer. I did work

on it for a while, but I never did accomplish a great deal.

BD: But in the

midst of all this you developed your

musicianship?

GG: I hope

so! I have a wide variety

of musical experiences, and they all contributed, in one way or

other, to one’s overall musical skills and perceptions. That’s a

lifelong pursuit. That never stops.

BD: When you were

directing

bands at WT, did you also conduct orchestras?

BD: When you were

directing

bands at WT, did you also conduct orchestras?

GG: Yes.

When I first went

there in 1963, my teaching assignment was as Band Director. Then

I taught all the woodwinds

except clarinet. We had a clarinet teacher, so I was teaching

oboe and bassoon and saxophone as well

as flute. Later we added a bassoonist and then later an

oboist, but the flute studio was growing all that time, and it

finally got to the point where I had twenty-five students in the flute

studio, plus doing the band, plus teaching some classes, which was more

than I could handle. I just felt that I was not doing

as good a job as I needed to do in anything because I was spread so

thin. So I reluctantly gave up the flute teaching at that

time. Then suddenly my schedule was wide open, and that also

coincided

with the departure of the orchestra director, so I also assumed

responsibility for the orchestra. Having had only limited

experience with stringed instruments, I did take violin lessons from

a member of our faculty for four years. I never did quite

reach the point I could stand to hear myself play, but it got a little

bit better and it accomplished its purpose. I learned enough

about strings to do a respectable job

with the orchestra.

BD: You were

leading ensembles of students who were learning, not quite yet

professional but

getting towards that level. You could impart a lot of musicality

to them and a lot of repertoire, I assume?

GG: We certainly

covered a lot of repertoire. I

don’t know what else they might have learned in there, but I hope

something...

BD: From the array

of band literature that is

available to you — and

I assume that it’s growing constantly — how do

you select which pieces to do this year or next year, or which ones you

won’t do at all?

GG: [Laughs]

You’re right about that, but I never looked quite that far ahead.

Many other conductors do, and they

have all my admiration, but I usually go one concert at a time.

There

are a lot of factors that go into the selection of

repertory, and you’re quite right, there are a lot of

pieces. I’d dare say most pieces I will never do

because my time’s too precious, and the time with the students is too

precious to do anything less than first-rate music.

BD: What is it

that makes a

piece of music first-rate?

GG: That’s a very

subjective

opinion. There are all sorts of things that go into it when I’m

selecting a piece of music to play. One is that I want

to expose the students to a variety of musical styles and periods. I’m

very

concerned with how idiomatic it is for the medium; how well

written it is for winds and percussion. That’s not quite so

subjective. The real subjective part of it

is in the harmonic content, the formal

content, the music itself. Is it well organized? Does it

make

sense? Is it appealing? That’s just something you have

to make a personal determination about.

BD: Did you find

that the students enjoyed the music which was being put on their stands?

GG: I would say

about eighty per cent of the

time. I tried to do a fair amount of contemporary music

— although not a steady

diet of it, by any means — and I would find,

especially with the younger

students, if it’s very contemporary (what they would think of as far

out

and wild) that a lot of younger students might have a

negative reaction to it. But as their familiarity of it

increased, then so did their appreciation. It would not be

unusual for a student to thoroughly dislike a piece

at first, but then by the time it was finally brought to the point of

performance, they were madly in love with it... although that’s not

invariable, either. Sometimes they still hated it.

[Both laugh] But that’s a subject of some interest to

me, and I have been very curious about that over the years.

Without fail I found that post-graduation, students’

musical taste had changed dramatically, and broadened dramatically,

which, of course, is a good thing.

*

* *

* *

BD: The band

literature doesn’t go back nearly as far as the orchestral literature,

so aside from arrangements you have more new works to play, or

more new works imposed on you. What advice do you have for

someone who wants to compose for the concert band?

GG: It’s a

wonderful medium to write for, for a

number of reasons. It has a very wide tonal spectrum, or tonal

pallate. It’s capable of so many diverse and wonderful

colors and sounds, but the big thing for an aspiring composer

is you can be performed. With the symphony orchestra these days,

it’s a tough spot. Orchestras are folding

around the

country, audiences are growing older, and the young people are not

coming along to take their places. This a broad generalization,

but for the most part the audiences don’t want to

hear much beyond the standard repertory — Mozart, Beethoven,

Brahms, maybe a

little Stravinsky on rare occasions — but if

it’s not part of

the standard repertoire, it’s kind of chancy, a little risky to

play. The orchestras have to be very concerned about what their

audiences are like because they are the ones who pay admission to

get in to hear the orchestra and keep the thing afloat.

BD: Because you

were in a

university situation...

GG: I didn’t have

to worry about that at all.

BD: Did that make

you freer to experiment?

GG:

Absolutely. But the point I was getting to is that a young

composer wanting to write for orchestra is very lucky to get a one

performance, but he is

extraordinarily lucky to get a second performance. That’s the

rule.

BD: Though with

the band there’s more chance?

GG: You bet!

If it’s a quality work, it’ll be

played over and over and over. He has a chance for great deal

more exposure and, as a matter of fact, for a great deal more financial

return.

BD: Does that put

more pressure on the composer to

make sure he gets it really right before the first performance?

GG: It wouldn’t be

a bad idea. [Lots of

laughter] But there are a lot of very important composers who

have written for band, many names you

recognize such as Aaron Copland, Paul Hindemith, Arnold Schoenberg, Vincent Persichetti,

William

Schuman, Walter Piston, and many, many others. [Names which are links refer to my

Interviews elsewhere on my website.]

GG: It wouldn’t be

a bad idea. [Lots of

laughter] But there are a lot of very important composers who

have written for band, many names you

recognize such as Aaron Copland, Paul Hindemith, Arnold Schoenberg, Vincent Persichetti,

William

Schuman, Walter Piston, and many, many others. [Names which are links refer to my

Interviews elsewhere on my website.]

BD: But it seems

that they’ve done mostly symphonic

and chamber works, and then dabbled for band, rather than being ‘band

composers’ like like Nelhybel

or Ron Nelson.

GG: Persichetti

contributed a large

number of pieces to the band literature, but

that’s a fair comment.

BD: Why is it that

we have professional

orchestras around the country and

around the world, but we don’t seem to have a lot of professional

bands? [When I asked this

question of Frederick

Fennell, he had a similar response.]

GG: There’s

certainly no easy answer to that, but I could maybe suggest a few

possibilities. One is

there’s not that long tradition. Another is in the minds of many

music ‘aficionados’, the band has sort of a bad rep. They

think of bands in terms of marching bands, and that means playing

trivial, cheap music. A lot of that we brought on ourselves, and

too often that is the case. This is a somewhat controversial

statement, but

the bands that are most highly thought of, the bands that

are probably regarded most highly are the service bands.

They’re wonderful bands. [See my Interview with

Captain William J. Phillips, Leader of the Navy Band.] It is

better now, but for much of their history they’ve traveled the country

playing mostly transcriptions, highlights from

Broadway shows, and a lot of marches, and not really very heavy or

serious concert fare. So that all contributes to their perception

of the band being a rather inferior medium of music performance.

BD: Is it safe to

assume that in your career

you tried to elevate the level of material put in front of the students?

GG: I don’t want

to sound too stuffy about it, but I did try to do that. Whether I

succeeded or not, I don’t know.

BD: I assume you

must have a number of alumni from your

bands who are now leading bands and orchestras.

GG: We have a

tremendous number of our former students

who are out teaching, and a great many of them, I’m happy to say, with

notable success. I don’t mean to sound

like a braggadocio at all

because I was not the only one, just a small part. We have a

wonderful music faculty here, and they all

contributed. One of the great things about this particular

school is that music education is not looked down upon, as it is in so

many places. Music education often is something thing you do if

you’re really not a very good performer. But throughout our

faculty,

everybody recognizes that it’s a noble calling, and that we need

talented, dedicated people in that field.

BD: It’s well

known all over that students from

Texas have a reputation for being first-rate musicians and first-rate

educators.

GG: Well, we in

Texas, think so! [Laughs]

BD: Isn’t it part

of your job to inspire as much

leadership as you can, as well as musicianship?

GG: That certainly

is the goal, yes.

*

* *

* *

BD: You’d grown

up with bands, and been a woodwind and brass man. Was it

difficult to then assume the orchestral

leadership?

GG: It was a new

challenge to be sure, and one that I

was very eager to take on. In many ways there’s no

difference. Music is music; quarter notes still get a

count in four-four time; it’s either in tune or it’s out of tune; it’s

either a phrase beautifully shaped or it’s not. There are far

more similarities than differences. The main differences between

stringed instruments and wind

instruments are in the manner of playing. That’s why I was eager

to study

violin so I would be a little bit better informed about the

problems with playing stringed instruments, and instructing the string

players.

BD: You did all of this

for many, many years. Did

you find that the general level of musicianship got higher and

higher each year?

BD: You did all of this

for many, many years. Did

you find that the general level of musicianship got higher and

higher each year?

GG: For many years

that was the case, but you reach a point at some time after enough

years where

you can’t continue to be going uphill all the time. As I look

back on it, there would be occasional dips where the band may not be as

good in some

respects as it was the previous year, and maybe in other respects it

was

better. The pendulum swings back and forth, and maybe

Section A will be down a little bit, and Section B will be

terrific. Then the leadership people in Section B graduate, and

the

people in Section A mature and come into their own. So there are

a lot

of little vacillations like that. I’m not sure that I would want

to say publicly which of the bands I

thought were the best. Many of them were...

BD: That’s just

putting

together the all-stars, but the general level though has kept up?

GG: Overall, yes,

probably so.

BD: Was it at all

frustrating for you to know that you

would work with the students, and nurture them for two, or three, or

four, or perhaps five years, and then they’re gone?

GG: [Laughs]

We had one student that was in

the band for eleven years! [Both laugh] He was a wonderful

player, and he just liked to go

to school. He was a pro when it came to

dropping classes, and he did that mainly because he didn’t want

to graduate. He wanted to hang around, but his dad

finally pulled the plug on that, so he went to classes and

graduated. But not very many of them anymore seem to graduate in

four years unless they also go in summers and take great heavy

loads.

It’s not at all that common. In fact, it’s quite common for them

to take five years, and not infrequently, more than that. But as

to your question, the saddest time of every year

for me was always the last concert because I knew when I gave that

final cut-off, that group would never ever be in the same place at

the same time again. It effectively ceased to exist, and it was

almost like a death in the family to me. It was always a

very emotional moment for me. I hated that time.

BD: Then in

September you had to start all over

again — not from scratch but from a few steps

back — and rebuild

and rebuild?

GG: I don’t mind

starting over. I like

that, and I love the rehearsals. The rehearsals are the best part

of it.

BD:

[Surprised] Really??? More than the performance?

GG: Yes. Not

that I didn’t enjoy

the performances, because I did and do, especially if they come off

well. But it’s the rehearsals where the real

teaching and congealing of the ensemble takes place. There is the

opportunity for communication, not just from the podium to the

ensemble, but from the ensemble back to the podium. It’s a

two-way process,

and it’s a very exciting one to me. I’m not at all

unusual in that way. I’ve heard a lot of conductors say exactly

the same thing. It’s the rehearsals that are great. That’s

what I miss the most — the daily musical give

and take.

BD: For any

particular concert, about how many

rehearsals did you have?

GG: That varied a

lot. I never even

stopped to think of it quite in those terms. In our case we

had four fifty-minute rehearsals a week, and then I excused the Friday

rehearsal in return for a section rehearsal with each section. So

that

was twelve sections. I’d have twelve one-hour section rehearsals

a week, plus four fifty-minute full rehearsals. I don’t know

how many rehearsals we normally had for a performance. Sometimes

it might be very few, sometimes it could be quite a few. It

depended a lot on how much we’re music playing, and the difficulty of

the music.

BD: Was it ever

enough time to rehearse?

GG: I remember several

years ago when we had Donald

Neuen, who was at that

time the director of choral activities at Eastman, in Rochester, New

York, came one summer. He had to do a choral workshop, and

another seminar they had. One of the students asked how much is

enough rehearsal, and he said, “There’s no such

thing as enough

rehearsal. You just keep rehearsing up till the time of the

concert, and then you perform.” But then

there are other people

that’ll say it’s possible to have too much rehearsal. As a matter

of fact, I’m one of those. I think that’s true. I think it

is possible

to have too much rehearsal. Then there’s no immediacy. It

tends to

dilute the immediacy of the rehearsal process, and take the pressure

off. Invariably where you have an excessive amount of time,

there’s still that last minute panic just as there was when there was

not enough time. Nowadays you can say there have been a lot of

performances that I’d conducted that I wished we’d had another

rehearsal or two, or that I had utilized the rehearsal time to better

effect.

GG: I remember several

years ago when we had Donald

Neuen, who was at that

time the director of choral activities at Eastman, in Rochester, New

York, came one summer. He had to do a choral workshop, and

another seminar they had. One of the students asked how much is

enough rehearsal, and he said, “There’s no such

thing as enough

rehearsal. You just keep rehearsing up till the time of the

concert, and then you perform.” But then

there are other people

that’ll say it’s possible to have too much rehearsal. As a matter

of fact, I’m one of those. I think that’s true. I think it

is possible

to have too much rehearsal. Then there’s no immediacy. It

tends to

dilute the immediacy of the rehearsal process, and take the pressure

off. Invariably where you have an excessive amount of time,

there’s still that last minute panic just as there was when there was

not enough time. Nowadays you can say there have been a lot of

performances that I’d conducted that I wished we’d had another

rehearsal or two, or that I had utilized the rehearsal time to better

effect.

BD: Was there ever

a case when you

purposely left something out so that there would be a special spark on

the night of performance?

GG:

[Decisively] No! [Both laugh] Neither do I

subscribe to the theory that a bad dress rehearsal means a good

concert. That’s a myth, at least in my

experience. I’ve had some bad dress rehearsals that

were followed by

bad concerts.

BD: Were you able

to coordinate the band and

orchestra programs with the rest of the ideas and classes and

lessons that were going on at the school of music?

GG: In some ways

there were. When our music history teacher would

be doing a seminar on Mozart, for example, he would want to

coordinate that with the playing of a Mozart symphony. That did

happen a number of times. Then there’s also a departmental

policy — this more of a pedagogical thing

— where we would all use the same

rhythmic counting systems so that the students would be getting the

same

thing in their theory class, in their individual private lessons,

and in their ensemble rehearsals — rather than

the ensemble

conductor using one counting system, and the private teacher using

another, and the theory teacher using still another, which would tend

to lead to confusion. So we did have a stated and unstated

departmental policy that would be all coordinated and uniform

throughout the department.

BD: In your

ensembles, were most, or all, music majors, or were some non-music

majors?

GG: In the

symphonic band, the top band, there would

usually be one or two or three non-music majors, but

almost all were music majors. Then there were some times when

there

were no non-music majors, but usually there would be two or three very

serious musicians who happened to be majoring in something outside

music. They were, without fail, wonderful band members and very

dedicated.

BD: Did you also

have the lower bands as well as the

top bands?

GG: I did for a

number of years, and then in 1987 we

brought in a second person who succeeded me that year. He was an

incredibly

talented musician. Up to that point I

had been doing both bands, and when he came on board, then he

took over what we call Concert Band.

BD: The Concert

Band would have a lot more

non-majors?

GG: Yes, they

would have more.

BD: Is there

anything different in your mind when

you’re giving a down-beat to non-majors as opposed to all majors?

GG: No. They

either respond or they don’t. They either play the right note or

they

don’t, and if they don’t, then it’s your job to try and lead them

to the right note.

BD: I just

wondered if there was some little

preparation, or a few extra things you would say at the beginning of

the rehearsal that

you would not say to those who were music majors.

GG: No, not for

me. Maybe somebody else would

feel differently but I certainly never thought of it in those terms.

*

* *

* *

BD: What’s the

purpose of music?

GG: [Surprised at

the question] Oh, God! I don’t know, and I don’t think

anybody else does. It’s a platitude, but music ennobles

and enriches the human soul. Fundamentally, as we know

throughout recorded history, human beings are incapable of existing

without it. We’ve got to have the arts in

general, whether it’s a drawing on a cave wall somewhere or the most

sophisticated twenty-first century art work in any medium. We

can’t exist without

it, we just can’t. Why that is I don’t know, but it

certainly seems to be ingrained, and it’s in that human gene pool, and

sure to stay as long as there are

humans around!

BD: Are you

optimistic about the whole future of

music, either performance or composition?

GG:

[Reluctantly] Well, yes and no. There seems to be a wide

chasm between the public and contemporary composers, which

has not been true throughout the course of music. I

guess this is the old fogey in me, but I think popular music is at such

an

all-time low. It’s depressing, and the pattern seems to

continue. Ever since I’ve known anything about it or have been

involved

in it, you go through periods of economic austerity

where the first thing that they want to cut is the arts. When the

Russian Sputnik went up in 1957, all of a

sudden there was this hue and cry around the country that, “The

Russians are

ahead of us! We need more math and science,”

and music and the

arts were under considerable assault for a while. I was

very much part of that era. I was just a young teacher then, and

it was

very alarming. So we go through periods like that, and here we

are

at a time where our nation’s economy is very tenuous, to say the least,

and I’m sure we’re going to hear a lot of that. In Alabama right

now they’re even thinking about

cutting out athletics! [Both laugh] But if athletics go,

you can be sure music’s going to go very soon. People seem to

think of music too

often as a frill. Well, it’s not a frill. Let’s face it,

instrumental music is a pretty expensive

proposition, but when it’s done right, there’s a tremendous

return. So I don’t know whether to be optimistic or not.

I’m

sure in the long-term things will be just fine, but these are difficult

times.

BD: You, as an

instructor, have to prepare the

youngsters for good times and bad.

GG: That’s true,

yes, and part of my assignment for much of my tenure was teaching

senior music methods classes — instrumental

music methods classes — and we’d talk about

things like that. They have to always be prepared to justify

their existence, and justify the very considerable expenditure that the

local school boards are putting forth to sustain their

programs. If they can’t do that, then they’ll be in real

jeopardy.

BD: They’ll be

looking for work elsewhere?

GG: That’s right,

and the real

losers will be the kids.

BD: I asked about

advice for

those who compose. What about those who want to conduct

bands? Do you have some advice for younger conductors coming

along?

GG: As far

as finding a job, that’s a wide-open field. There’s a

considerable shortage, at least in this state, of band directors right

now, and a serious shortage of orchestra teachers.

BD: Why is that?

GG: I’ve

done some research on this, and the really talented string players

— who are also very bright kids — are

likely to go into

medicine, or law, or engineering, heaven knows what.

BD: Anything but

music?

GG: Yes, and if

they do go into music, they think

they need to be performers, and most likely to want to go to an Eastern

conservatory. That’s a very tough road to make a career as a

player. It’s very hard because there’s such a vast pool of people

seeking employment in professional orchestras, and so few openings come

about. There might be a thousand applicants for a job, and you’re

very lucky

if you even get to audition. Statistically I always tell

kids, “Why don’t you plan to be a United States

Senator? There are a hundred of them, but if you’re a tuba

player and you get a degree in tuba, maybe there’ll be an opening

some time in the next ten years in an orchestra, and maybe you’ll be

one

of the thousand people that’ll apply for it.”

So that’s a

very, very difficult career goal, but there are jobs that come about

occasionally, and somebody will get them. They just have to be

realistic and understand that the odds are stacked badly

against them.

BD: Let’s now

assume that someone has

beaten the odds and is the conductor. What kind of advice do you

have for the working conductor?

GG: You mean in a

public school situation?

BD: Or in a

university situation.

GG: What they need

to do is prepare for it. They need to do a number

of things. First of all, they need to be the best

performers they can. If

you’ve never really made music at a very high level, it’s not

likely you’re going to teach anybody to play at a very high

level. They need to be as serious as they can about

music

theory, and learn how music works. They need to know something

about music history — which is something that I

certainly poo-pooed at

one time in my life — and they need to know as

much repertoire as they

can. They need to study the repertoire for that medium, and hear

as many performances as they can, see as many rehearsals as they can,

observe as many conductors as they can, see what they like and what

they

don’t like, find what they want to use and what they want to avoid,

because you learn something from everybody — even

if

it’s what not to do. They would be very well advised

to do what I didn’t do, which is to develop at least a modicum of

keyboard expertise, and continue to try to develop aural acuity,

as well as just the mechanical act of conducting. It’s something

that needs to be studied and

practiced. It’s like playing an instrument.

BD: You did take some of

your advice by becoming a first-rate flute player. Tell me about

some of the joys

and sorrows of being a flute player — or do you say

‘flautist’?

BD: You did take some of

your advice by becoming a first-rate flute player. Tell me about

some of the joys

and sorrows of being a flute player — or do you say

‘flautist’?

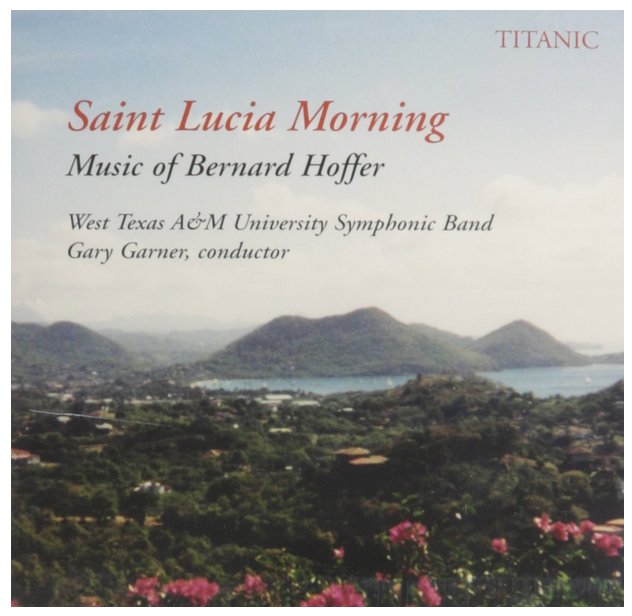

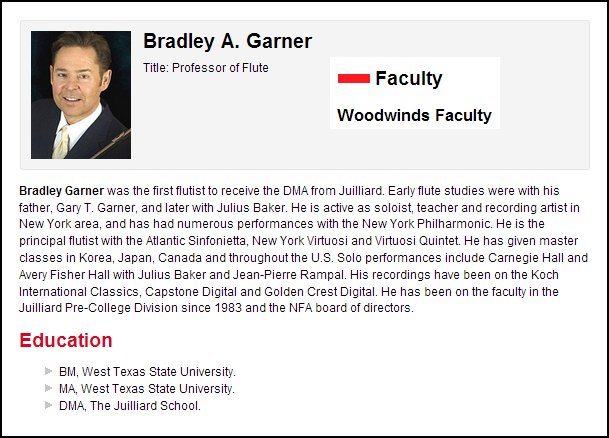

GG: I call it

‘flutist’, or as my son would say

a ‘flutician’! [Laughs] Actually he borrowed that from his

teacher, Julius

Baker. The flute turned out to be a good

instrument for me. I seem to be fairly well suited to it, and

there are great things about. Because most the flute

players are girls, if you’re only guy in a section of girls, that’s

not bad. [Laughs] And you get to play the melody all the

time. It’s very portable. It’s a lovely instrument, and

there’s a lot of

great flute literature.

BD: Both solo and

for flute ensemble?

GG: Yes... well, I

don’t know if I would say there is a lot of

great flute ensemble literature. There’s a lot of flute ensemble

literature, but I don’t know how much of it is

great. Forgive

the immodesty, but my son’s the best flute player I know of, and he has

an

unbelievable flute studio at the Cincinnati Conservatory that’s highly

selective, and he avoids ‘flute choirs’ like the plague. Even

though he’s got all these

wonderful players at his disposal, he just doesn’t think there’s much

really good music.

BD: Does he

discourage it, or does he just simply

leave it to someone else?

GG: I don’t know

that he discourages anybody

else doing it, but he just says there’s not enough good music to

justify spending time on

it. But there’s certainly a wealth of good solo material,

and the orchestral repertoire is replete with wonderful

flute parts. So it’s a great instrument to

play. You don’t have to worry about reeds, which is a very

big plus, and you don’t have to worry about chops in the way that brass

players do. So in strictly practical ways, I can’t imagine why

anybody else would play anything else, to tell you the truth.

[Laughs again]

BD: [With a gentle

nudge] But you don’t want everyone to play flute.

You need the whole rest of the orchestra.

GG: Although

sometimes these days, it seems as if

everyone is. If you’ve ever gone to an annual meeting of the

National Flute Association, flute

players turn out by the thousands. It’s mind-boggling. I’m

sure they represent just a small proportion of the

flute players around the country. When I was a

kid and started playing the flute, there were not many flute

players. But now, my gosh, they just multiply like

nobody’s business.

BD: I assume every

flute player should also play

piccolo, and alto flute, and bass flute?

GG: No, not

necessarily. A lot of flute players

don’t like to play piccolo, and I’m one of them. I never really

cared much

for playing piccolo. But then there are a lot of people who

specialize on the flute, and I notice there are a lot of wonderful

piccolo players who are not as good on flute as they are on

piccolo. This is not always the case, of course. Alto

flute’s a lot of fun

to play, and you don’t often need a bass flute! I probably

haven’t spent an hour on a bass

flute in my life, but it’s fun to play.

BD: You should

write a concerto for bass flute.

GG: There may be

one, but you hear it in movie scores and sometimes in

commercial music. A lot of ‘flute

choir’ music calls for bass flute.

*

* *

* *

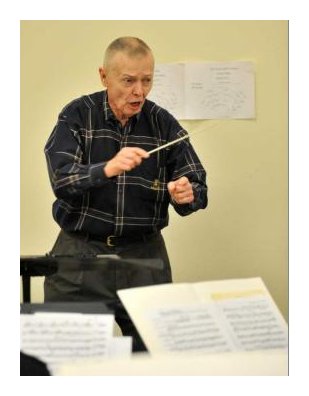

BD: One last

question. Is conducting fun?

BD: One last

question. Is conducting fun?

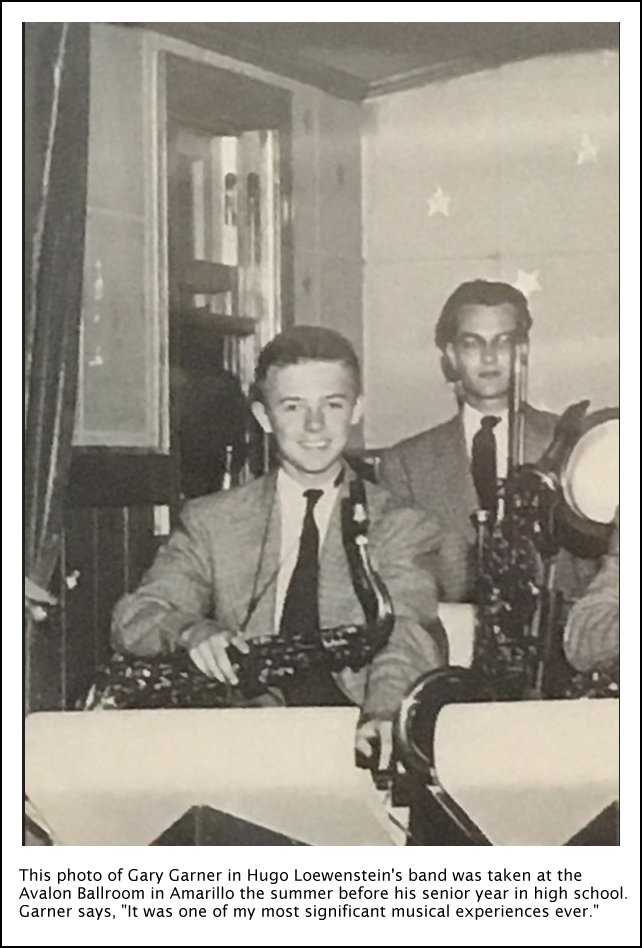

GG: Conducting is

way beyond fun. It’s exhilarating, and I do warn my

students about this. There’s such a sense of power that sweeps

over you up on that podium, where you’re in total control of all these

people in front of you, it’s sometimes

easy get a little too carried away with it.

BD: Are you in

control, or are you just trying

to bring out everything that’s in the score?

GG: You’re in

control in the sense that you

could tell them what to do. Whether or not they’re able to do

it is quite another matter, but you’re in charge. It is

easy, especially in a school situation, to abuse that

if you’re not careful. This is something a lot of people have to

be careful to avoid.

BD: You’ve retired

from WT?

GG: I still get

back there a little bit. I taught

at the band camp again this summer, and I help with a band clinic they

have in the spring. In the spring I do a lot of band clinics for

high school and bands. Last year I began volunteering my time at

a local high

school. It all began actually when I was visiting a former

student who’d had an appendectomy at the hospital

here. A Pink Lady was

showing me her room, and I was thinking what a nice thing it was that

this woman was volunteering her time in this way. So I needed to

do that, too. For some reason they rejected my application to be

a

Pink Lady [winks], but I had been giving some serious

thought about how I might do some volunteer work, when finally the

obvious came to me. The one thing I’d like to do most, and

perhaps do

the best, is work with school instrumental ensembles. So I

called a former student of mine, who is a director at a local high

school, and told him I’d be glad to come out one day a week and help in

whatever way he’d like, and he was kind enough to say yes. So I

did that one day a week for a week or two, and had so much fun, I

started doing it two times a week. Before I knew it, I was going

out there every day, and probably will do the same thing again this

year. So that’s taken up some time, but it’s been a most

pleasurable pursuit for me.

BD: Thank you for

all you have given to music, and I

hope you continue to have lots of great success.

GG: You’re very

kind, and I join you in that

hope. Thank you.

© 2003 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at his home in Texas in

September, 2003. Portions were broadcast on WNUR in 2006, and

on Contemporary Classical Interenet Radio in 2007 and 2013.

This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this

website

at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una

Barry for her help in preparing this website

presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until

its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His

interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980,

and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well

as

on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

The

next leg of our journey was west, across the deep south to Texas,

to visit Kathy’s

mother in Plainview. It was there that Kathy, a graduate of WT,

and who had played clarinet in Garner’s

ensemble for several years, contacted her former bandmaster and

arranged for this interview before we headed back home to Chicago.

The

next leg of our journey was west, across the deep south to Texas,

to visit Kathy’s

mother in Plainview. It was there that Kathy, a graduate of WT,

and who had played clarinet in Garner’s

ensemble for several years, contacted her former bandmaster and

arranged for this interview before we headed back home to Chicago. BD: When you were

directing

bands at WT, did you also conduct orchestras?

BD: When you were

directing

bands at WT, did you also conduct orchestras? GG: It wouldn’t be

a bad idea. [Lots of

laughter] But there are a lot of very important composers who

have written for band, many names you

recognize such as Aaron Copland, Paul Hindemith, Arnold Schoenberg, Vincent Persichetti,

William

Schuman, Walter Piston, and many, many others. [Names which are links refer to my

Interviews elsewhere on my website.]

GG: It wouldn’t be

a bad idea. [Lots of

laughter] But there are a lot of very important composers who

have written for band, many names you

recognize such as Aaron Copland, Paul Hindemith, Arnold Schoenberg, Vincent Persichetti,

William

Schuman, Walter Piston, and many, many others. [Names which are links refer to my

Interviews elsewhere on my website.] BD: You did all of this

for many, many years. Did

you find that the general level of musicianship got higher and

higher each year?

BD: You did all of this

for many, many years. Did

you find that the general level of musicianship got higher and

higher each year? GG: I remember several

years ago when we had Donald

Neuen, who was at that

time the director of choral activities at Eastman, in Rochester, New

York, came one summer. He had to do a choral workshop, and

another seminar they had. One of the students asked how much is

enough rehearsal, and he said, “There’s no such

thing as enough

rehearsal. You just keep rehearsing up till the time of the

concert, and then you perform.” But then

there are other people

that’ll say it’s possible to have too much rehearsal. As a matter

of fact, I’m one of those. I think that’s true. I think it

is possible

to have too much rehearsal. Then there’s no immediacy. It

tends to

dilute the immediacy of the rehearsal process, and take the pressure

off. Invariably where you have an excessive amount of time,

there’s still that last minute panic just as there was when there was

not enough time. Nowadays you can say there have been a lot of

performances that I’d conducted that I wished we’d had another

rehearsal or two, or that I had utilized the rehearsal time to better

effect.

GG: I remember several

years ago when we had Donald

Neuen, who was at that

time the director of choral activities at Eastman, in Rochester, New

York, came one summer. He had to do a choral workshop, and

another seminar they had. One of the students asked how much is

enough rehearsal, and he said, “There’s no such

thing as enough

rehearsal. You just keep rehearsing up till the time of the

concert, and then you perform.” But then

there are other people

that’ll say it’s possible to have too much rehearsal. As a matter

of fact, I’m one of those. I think that’s true. I think it

is possible

to have too much rehearsal. Then there’s no immediacy. It

tends to

dilute the immediacy of the rehearsal process, and take the pressure

off. Invariably where you have an excessive amount of time,

there’s still that last minute panic just as there was when there was

not enough time. Nowadays you can say there have been a lot of

performances that I’d conducted that I wished we’d had another

rehearsal or two, or that I had utilized the rehearsal time to better

effect.

BD: You did take some of

your advice by becoming a first-rate flute player. Tell me about

some of the joys

and sorrows of being a flute player — or do you say

‘flautist’?

BD: You did take some of

your advice by becoming a first-rate flute player. Tell me about

some of the joys

and sorrows of being a flute player — or do you say

‘flautist’? BD: One last

question. Is conducting fun?

BD: One last

question. Is conducting fun?