VP: That's a hard question for

me to answer. I would like people to come to hear my music having

known some of the music of my colleagues or music of our time, or other

music of mine so they can understand my language. I hope they'll

hear what I'm saying. [Pauses for a moment] I'm not getting

far with this...

VP: That's a hard question for

me to answer. I would like people to come to hear my music having

known some of the music of my colleagues or music of our time, or other

music of mine so they can understand my language. I hope they'll

hear what I'm saying. [Pauses for a moment] I'm not getting

far with this...  VP: [Thinks for a

moment] It's a work that is saying more about less instead of

less about more. So a good piece would be a work that doesn't

spread all over the place. One meaningful, beautiful thing after

another doesn't make a good piece; to me that becomes kind of a

newsreel. A piece that has a limited amount of material and spins

out of this and enlarges the content toward what I call the better

music of our time really makes a good piece. Beethoven will write

a whole sonata or symphony about just a slight motivic clunk of

stuff. In fact, often his first theme might be about something

weak; not that he's writing weak music, but he will be trying to get

that first subject to get some health and energy in it, and grow into

what we call a second subject or a B subject. They're not two

different subjects; the second subject is the growth from the original

opening idea. Then there'll be a closing subject that will gather

up little segments of the first part and the second part that makes a

temporary close. They're the pieces I think are the better

ones. They just deal with less material and say more.

VP: [Thinks for a

moment] It's a work that is saying more about less instead of

less about more. So a good piece would be a work that doesn't

spread all over the place. One meaningful, beautiful thing after

another doesn't make a good piece; to me that becomes kind of a

newsreel. A piece that has a limited amount of material and spins

out of this and enlarges the content toward what I call the better

music of our time really makes a good piece. Beethoven will write

a whole sonata or symphony about just a slight motivic clunk of

stuff. In fact, often his first theme might be about something

weak; not that he's writing weak music, but he will be trying to get

that first subject to get some health and energy in it, and grow into

what we call a second subject or a B subject. They're not two

different subjects; the second subject is the growth from the original

opening idea. Then there'll be a closing subject that will gather

up little segments of the first part and the second part that makes a

temporary close. They're the pieces I think are the better

ones. They just deal with less material and say more.  VP: I think I am. I kinda

stem

from Haydn and Schumann and maybe Rossini and Verdi. In fact, my

family on my father's side was from Torricella Peligna [a village in

Abruzzo], where Rossini's family came from. [Note: Persichetti

says in an interview in Perspectives

of New Music (v. 20, no. 1/2 (Autumn 1981-Summer 1982, p. 104)

that it was the Bellini family; neither legend, however, seems correct

as Rossini was from Pesaro, in Marche, while Bellini was Sicilian, and

lived in Naples.] I've always felt very close to Robert Schumann

and somewhat Haydn. Haydn interests me because he makes so many

promises that he doesn't fulfill! I'm not criticizing him; I love

his music, but in his introductions he'll start out [sings up a minor

scale] BOOMP-BOOMP-BOOMP-BOOMP, the giants going up the stairs

and shaking their fists and just about to break loose, and he goes

[sings a very brisk, happy-sounding melody] da-DEEE, dup ba

beedabeeda ba-ba-ba, and starts to dance. [Both laugh] So I

have found much in that part of Haydn that perhaps he didn't want to

get into. That's always stimulated me. And Arthur Honegger

very much because he upturned a lot of material and really didn't go on

with it. There are wonderful things here and there that stimulate

creativity.

VP: I think I am. I kinda

stem

from Haydn and Schumann and maybe Rossini and Verdi. In fact, my

family on my father's side was from Torricella Peligna [a village in

Abruzzo], where Rossini's family came from. [Note: Persichetti

says in an interview in Perspectives

of New Music (v. 20, no. 1/2 (Autumn 1981-Summer 1982, p. 104)

that it was the Bellini family; neither legend, however, seems correct

as Rossini was from Pesaro, in Marche, while Bellini was Sicilian, and

lived in Naples.] I've always felt very close to Robert Schumann

and somewhat Haydn. Haydn interests me because he makes so many

promises that he doesn't fulfill! I'm not criticizing him; I love

his music, but in his introductions he'll start out [sings up a minor

scale] BOOMP-BOOMP-BOOMP-BOOMP, the giants going up the stairs

and shaking their fists and just about to break loose, and he goes

[sings a very brisk, happy-sounding melody] da-DEEE, dup ba

beedabeeda ba-ba-ba, and starts to dance. [Both laugh] So I

have found much in that part of Haydn that perhaps he didn't want to

get into. That's always stimulated me. And Arthur Honegger

very much because he upturned a lot of material and really didn't go on

with it. There are wonderful things here and there that stimulate

creativity.  VP: That's right,

and

conductors could do this. I'm speaking about major orchestra

because that probably does more for our careers than anything in the

public way. I wish that each conductor would find a piece that he

really loves and would then program that piece again the following year

and three years later and have a repetition of those works. We

know it has happened with Stravinsky and Bartók, but I'm talking

about the more recent composers. Wouldn't you rather just have

three works that you found a conductor liked? Even if you didn't

like the work, the fact that he liked it and kept doing it would be

significant. The string quartets do that more than the conductors

do. We have to have more people to stick their neck out.

VP: That's right,

and

conductors could do this. I'm speaking about major orchestra

because that probably does more for our careers than anything in the

public way. I wish that each conductor would find a piece that he

really loves and would then program that piece again the following year

and three years later and have a repetition of those works. We

know it has happened with Stravinsky and Bartók, but I'm talking

about the more recent composers. Wouldn't you rather just have

three works that you found a conductor liked? Even if you didn't

like the work, the fact that he liked it and kept doing it would be

significant. The string quartets do that more than the conductors

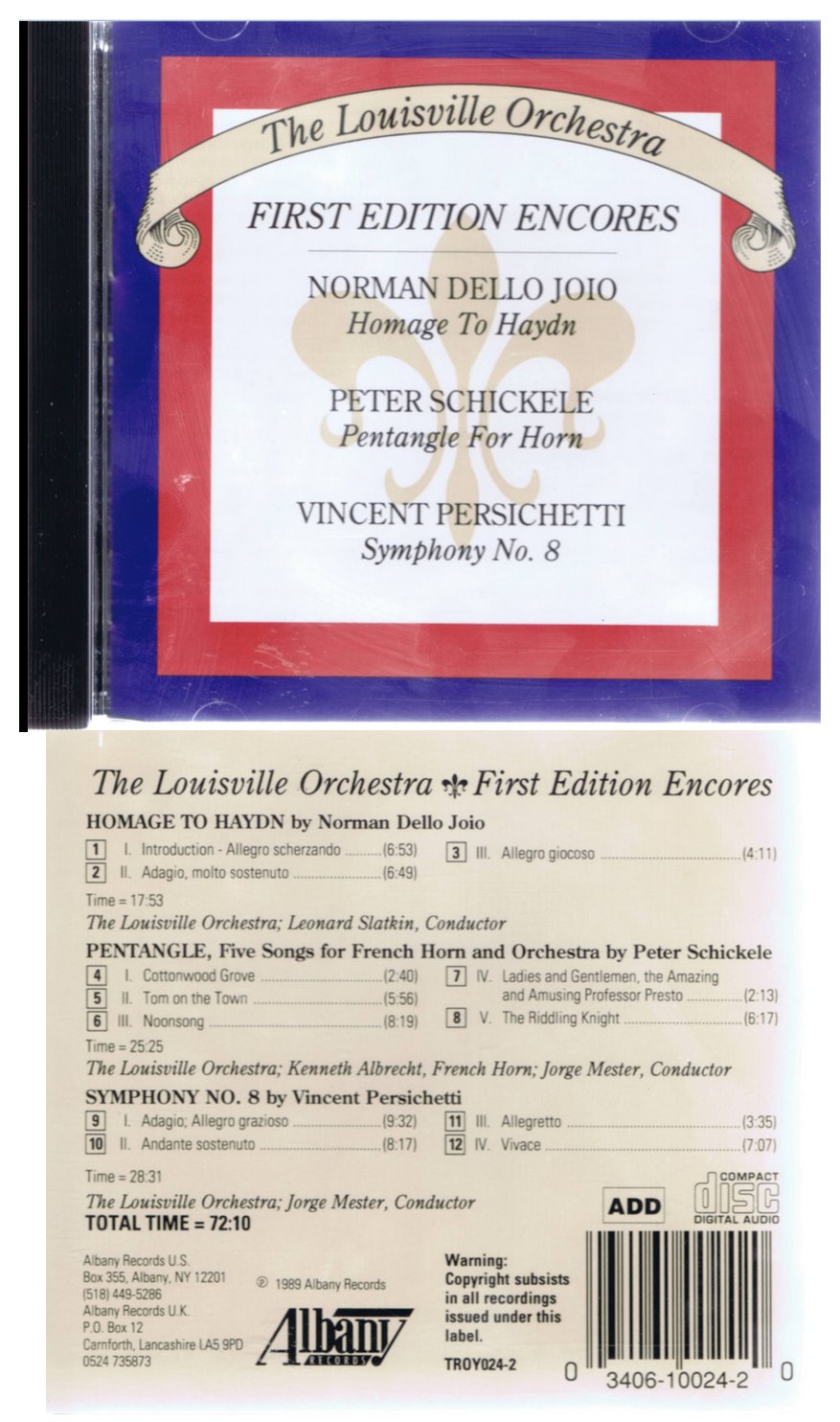

do. We have to have more people to stick their neck out.  VP: Yes, I would say

so. I've been very lucky with performances. For instance,

Robert Whitney in the early days and the Louisville Orchestra; I was

pleased with that because those people played so many different kinds

of music that they could understand more easily what I was trying to

do, and they gave it rehearsal time. Also the Juilliard String

Quartet; we have so many of these groups around this country that get

right to the core of the music. And certainly the Chicago

Symphony; I go back to that. But I find wonderful performances by

wonderful orchestras and bands in the universities around the

country. They may not be the top performers since

they're students, but they have played so much 20th century music that

they know how to shape the phrases in a beautiful manner — almost

an alarming manner. [Chuckles] They'll find something there

that you maybe didn't quite even dream of, and make something of it,

whereas sometimes the professional orchestras don't always get it as

quickly. The bands have done a lot for getting into

contemporary music. I'm not talking about weak band music, but

there's been some strong band music. These people aren't that

proficient at playing; they have to work harder but they do this all

through high school and college, and by the time they get to the end of

college they know what our music is about and can sit down and play it

with phrase meaning and shape and with some conviction. So yes,

I've gotten a lot of very meaningful performances. I'm sure I'm

skipping so many that I've had, but a lot of it comes from the schools.

VP: Yes, I would say

so. I've been very lucky with performances. For instance,

Robert Whitney in the early days and the Louisville Orchestra; I was

pleased with that because those people played so many different kinds

of music that they could understand more easily what I was trying to

do, and they gave it rehearsal time. Also the Juilliard String

Quartet; we have so many of these groups around this country that get

right to the core of the music. And certainly the Chicago

Symphony; I go back to that. But I find wonderful performances by

wonderful orchestras and bands in the universities around the

country. They may not be the top performers since

they're students, but they have played so much 20th century music that

they know how to shape the phrases in a beautiful manner — almost

an alarming manner. [Chuckles] They'll find something there

that you maybe didn't quite even dream of, and make something of it,

whereas sometimes the professional orchestras don't always get it as

quickly. The bands have done a lot for getting into

contemporary music. I'm not talking about weak band music, but

there's been some strong band music. These people aren't that

proficient at playing; they have to work harder but they do this all

through high school and college, and by the time they get to the end of

college they know what our music is about and can sit down and play it

with phrase meaning and shape and with some conviction. So yes,

I've gotten a lot of very meaningful performances. I'm sure I'm

skipping so many that I've had, but a lot of it comes from the schools. VP: I would like it to be

for them. Honestly, I would prefer having

it done in English because that's how it was written. But if it

had gotten to that point, I don't see why it shouldn't be translated

into French or whatever.

VP: I would like it to be

for them. Honestly, I would prefer having

it done in English because that's how it was written. But if it

had gotten to that point, I don't see why it shouldn't be translated

into French or whatever. VP: Hindemith said that

you should know about the shape of the whole piece, and I agree with

him, but not at the start. We start with a motive, then we're

kind of seduced by some harmonic place and we let it go for awhile, not

trying to be intelligent about it, just let it go. At least

that's what I do, anyway. Then later will come some other

subsidiary ideas for that kind of piece, and gradually I begin to see a

piece. Then it begins to take shape, and at about that point we

have to get in there cold and understand it like Hindemith said.

Sometimes I arrive at that, sometimes I don't — in which

case I don't finish the piece. But if I arrive at that point,

then I know how long a piece will be. I don't mean in minutes,

but where it's going to go. If I finally get to that point where

I realize that concept, that flash I had, then I know the piece is

done, with the exception of going maybe further into the polishing of

ideas. For instance, there could be a place in the middle where

you have an accompanying figure that was just kind of filler and it

happened accidentally. You know what to do, but as you see the

whole piece, maybe there's a figure that's not thematically related to

something, so I will start changing and putting more carats in the

gold there at that point in order to get my final concept of the

piece. But the time comes when I know the piece is done.

VP: Hindemith said that

you should know about the shape of the whole piece, and I agree with

him, but not at the start. We start with a motive, then we're

kind of seduced by some harmonic place and we let it go for awhile, not

trying to be intelligent about it, just let it go. At least

that's what I do, anyway. Then later will come some other

subsidiary ideas for that kind of piece, and gradually I begin to see a

piece. Then it begins to take shape, and at about that point we

have to get in there cold and understand it like Hindemith said.

Sometimes I arrive at that, sometimes I don't — in which

case I don't finish the piece. But if I arrive at that point,

then I know how long a piece will be. I don't mean in minutes,

but where it's going to go. If I finally get to that point where

I realize that concept, that flash I had, then I know the piece is

done, with the exception of going maybe further into the polishing of

ideas. For instance, there could be a place in the middle where

you have an accompanying figure that was just kind of filler and it

happened accidentally. You know what to do, but as you see the

whole piece, maybe there's a figure that's not thematically related to

something, so I will start changing and putting more carats in the

gold there at that point in order to get my final concept of the

piece. But the time comes when I know the piece is done. VP: I'm always in more

than one piece — two, three, four. I've never been

between

works. I may be working on a symphonic work and have it in a

semi-finished stage. A lot of that is scoring and detail and

adjustments, so I'm free creatively. Somehow or other I begin to

get ideas for some other piece before that piece is over. So I'll

often have three pieces working in different states. At a time

when I'm really hot on a piece, especially in the beginning of it and

getting material, I don't work on another piece at that time; but later

in that first piece I will find myself getting finishing ideas on

another piece or initial ideas on a new piece. I'm always

thinking about some new piece, and these are not because of

commissions; I just get into it. As I said I don't really write

on commission. I just have to write what I want to write, and I'm

delighted when commissions go along side. It's nice to have your

parts paid for.

VP: I'm always in more

than one piece — two, three, four. I've never been

between

works. I may be working on a symphonic work and have it in a

semi-finished stage. A lot of that is scoring and detail and

adjustments, so I'm free creatively. Somehow or other I begin to

get ideas for some other piece before that piece is over. So I'll

often have three pieces working in different states. At a time

when I'm really hot on a piece, especially in the beginning of it and

getting material, I don't work on another piece at that time; but later

in that first piece I will find myself getting finishing ideas on

another piece or initial ideas on a new piece. I'm always

thinking about some new piece, and these are not because of

commissions; I just get into it. As I said I don't really write

on commission. I just have to write what I want to write, and I'm

delighted when commissions go along side. It's nice to have your

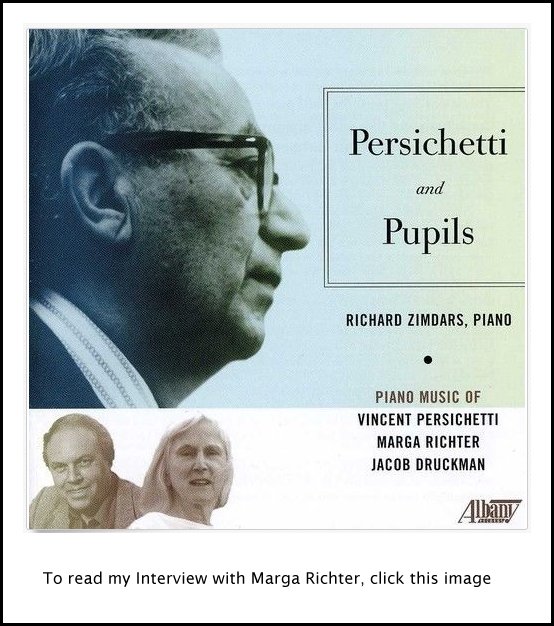

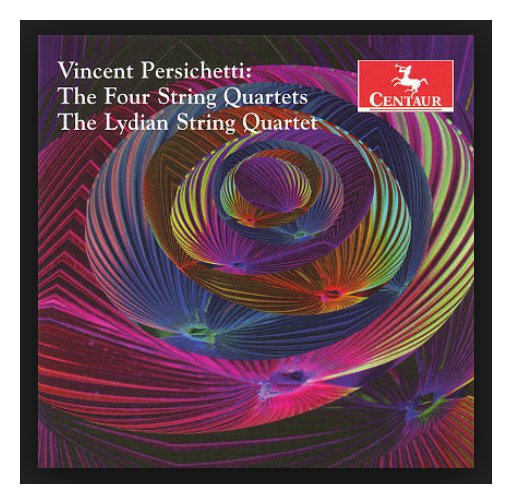

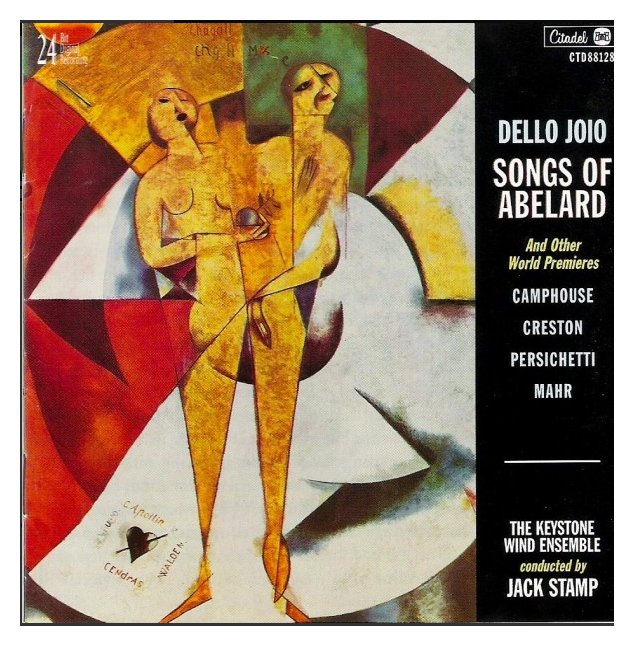

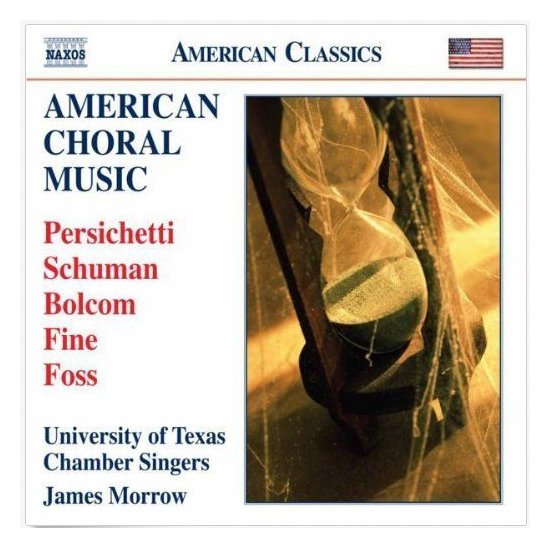

parts paid for.Happily, there are more and more

CDs with music of Vincent Persichetti,

and many of them also contain pieces by other composers. Here are just a few which include some of my interview guests . . . . .  To read my Interview with Norman Dello Joio, click HERE. To read my Interview with Jack Stamp, click HERE.   To read my Interview with William Schuman, click HERE. To read my Interview with Lukas Foss, click HERE.   To read my Interview with Christopher Keene, click HERE. To read my Interview with James DePreist, click HERE. To read my Interview with David Diamond, click HERE. To read my Interview with Milton Babbitt, click HERE.   To read my Interview with Samuel Baron, click HERE. To read my Interview with Matthias Bamert, click HERE.   To read my Interview with Peter Schickele, click HERE. To read my Interviews with Leonard Slatkin, click HERE. To read my Interview with Jorge Mester, click HERE. |

|

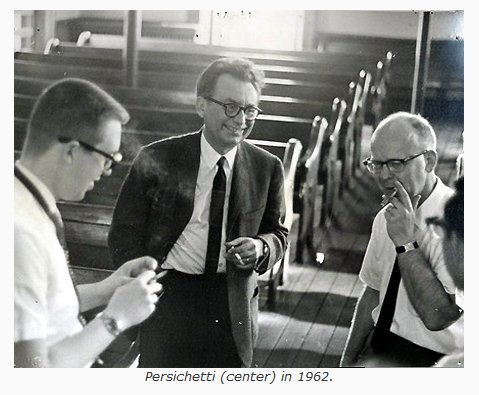

There have been few more universally admired twentieth-century American composers than Vincent Persichetti. His contributions have enriched the entire musical literature and his influence as performer and teacher is immeasurable. Born in Philadelphia in 1915, Persichetti began his musical life at age five, first studying piano, then organ, double bass, tuba, theory and composition. By the age of 11, he was paying for his own musical education and helping to support himself by performing professionally as an accompanist, radio staff pianist, orchestra member and church organist. At 16, he was appointed organist and choir director for the Arch Street Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, a post he held for nearly 20 years. A virtuoso pianist and organist, he combined extraordinary versatility with an osmotic musical mind, and his earliest published works, written when the composer was 14, exhibit mastery of form, medium and style.

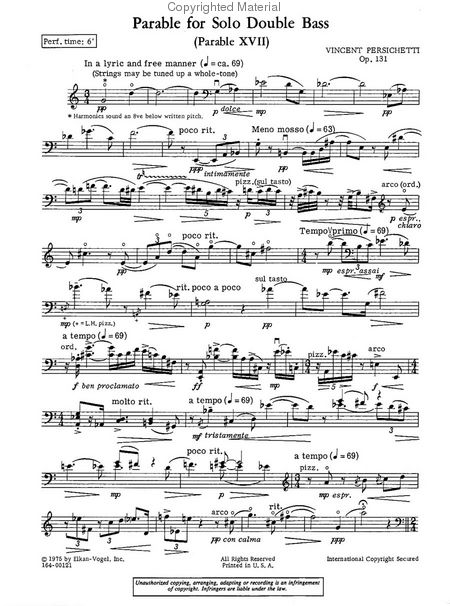

In 1941 Persichetti was appointed head of the theory and composition departments at the Philadelphia Conservatory and in the same year married pianist Dorothea Flanagan. A daughter Lauren, was born in 1944 and a son, Garth, in 1946. In 1947 he joined the faculty of the Juilliard School of Music, assuming chairmanship of the Composition Department in 1963. Persichetti was appointed Editorial Director of the music publishing firm of Elkan-Vogel, Inc. in 1952. Over the years, Vincent Persichetti was accorded many honors by the artistic and academic communities, including Honorary Doctor of Music degrees from Bucknell University, Millikin University, Arizona State University, Combs College, Baldwin-Wallace College, Peabody Conservatory, and honorary membership in numerous musical fraternities. He was the recipient of three Guggenheim Fellowships, two grants from the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities and one from the National Institute of Arts and Letters, of which he was a member. He received the first Kennedy Center Friedheim Award, Brandeis University Creative Arts Award, Pennsylvania Governor’s Award, Columbia Records Chamber Music Award, Juilliard Publication Award, Blue Network Chamber Music Award, Symphony League Award, Philadelphia Art Alliance Medal for Distinguished Achievement, Medal of Honor from the Italian Government, and citations from the American Bandmasters Association and National Catholic Music Educators Association. Among some 100 commissions were those from the Philadelphia Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the St. Louis and Louisville Symphony Orchestras, the Koussevitsky Music Foundation, Naumberg Foundation, Collegiate Chorale, Martha Graham Company, Juilliard Musical Foundation, Hopkins Center, American Guild of Organists, Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival, universities and individual performers. He appeared as guest conductor, lecturer and composer at over 200 universities. Wide coverage by the major TV and news media of the premiere of his A Lincoln Address helped to focus worldwide attention on his music. Persichetti composed for nearly every musical medium. More than 120 of his works are published and many of these are available on commercial recordings. Though he never specifically composed "educational" music as such, many of his smaller pieces are suitable for teaching purposes. His piano music, a complete body of literature in itself, consists of six sonatinas, three volumes of poems, a concerto and a concertino for piano and orchestra, serenades, a four-hand concerto, a two-piano sonata, twelve solo piano sonatas, and various shorter works. His keyboard virtuosity led him to produce nine organ works, including Sonatina for Organ, Pedals Alone, and the dramatic Shimah B’Koli (Psalm 130), as well as nine sonatas for harpsichord. Persichetti’s style of orchestral writing reflected his considerable talent and experience as a conductor. Of his symphonies, several, notably the Fourth, Fifth (Symphony for Strings), and Eighth, have made their way into the repertoire of major American symphonic ensembles. The Seventh Symphony was a very personal statement and is a symphonic development of materials from his small choral book Hymns and Responses for the Church Year. Another large important orchestral work, commissioned for the Philadelphia Orchestra, is Sinfonia: Janiculum, written while Persichetti was in Rome on his second Guggenheim Fellowship. The most famous of his smaller orchestral works, and one firmly established in American symphonic literature, is The Hollow Men for trumpet and string orchestra, a delicate evocation of the T.S. Eliot poem. Three of his last commissions were the English Horn Concerto (New York Philharmonic), Flower Songs: Cantata No. 6 (Michael Korn and the Philadelphia Singers), and Chorale Prelude: Give Peace, O God (Ann Arbor chapter of the American Guild of Organists). The numerous instrumental

compositions include two unique series: one comprises 15 different

works each entitled Serenade

for such diverse combinations as piano duet, flute and harp, solo tuba,

orchestra, band, two recorders, two clarinets and the trio of trombone,

viola and cello. The series of 25 pieces, each entitled Parable,

occupied Persichetti’s thoughts for some time. He also wrote four

string quartets, a piano quintet, solo sonatas for violin and cello, Infanta

Marina for viola and piano, Little Recorder Book, and Masques

for violin and piano, to name just a few. Persichetti’s unusual feeling for poetry produced numerous vocal and choral compositions of remarkably high literary and musical quality. His greatest solo vocal work is undoubtedly Harmonium, an impressive cycle of 20 closely interrelated songs to poems by Wallace Stevens. Though not of the same magnitude as Harmonium, Persichetti’s other vocal compositions exhibit a unique wedding of text and music which sets them apart from most other composers’ efforts in this genre. His choral output ranges from small works such as Proverb for mixed voices, Song of Peace for male chorus and piano, Spring Cantata for women’s voices and piano, through larger works: Mass for mixed chorus a cappella, Winter Cantata for women’s voices, flute and marimba, and Glad and Very for two-part mixed, women’s or men’s voices and piano, and then to large scale sacred and secular works: The Pleiades for chorus, trumpet and string orchestra, Celebrations for chorus and wind ensemble, and what Persichetti considered to be his magnum opus, The Creation, a huge work for solo vocal quartet, chorus and orchestra with texts drawn by the composer from mythological scientific, poetic and Biblical sources. The small but significant choral book Hymns and Responses for the Church Year, has already been influential in breathing a new spirit into twentieth-century hymnody. More than any other major American composer, Persichetti poured his talents into the literature for wind band. From the Serenade for Ten Wind Instruments, Op. 1 to the Parable for Band, Op. 121, he provided performers and audiences with a body of music of unparalleled excellence. Of his 14 band works, four are of major proportions: Masquerade, Parable, A Lincoln Address and Symphony for Band. Of lesser compositional importance, the Divertimento is nevertheless one of the most widely performed works in the entire repertoire. In additions to his exhaustive compositional efforts, Persichetti found time to write one of the definitive books on modern compositional techniques, Twentieth Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice (W.W. Norton, 1961) and essays in two books by Robert Hines on twentieth century choral music and twentieth century orchestral music (University of Oklahoma Press, 1963 and 1970). He also co-authored a biography of William Schuman (G. Schirmer, 1954). To a new, adventurous

generation of composers — fortunately, large and musically eloquent —

he was a teacher par excellence

and a highly lucid theorist. In both capacities his great artistry was

ever clear and impressive, providing an example of dynamic leadership

for those who encountered his genius. ---- Biography from

Persichetti's publisher, Theodore Presser Company |

PUBLSIHED WORKS

CONCERT BAND A Lincoln Address, Op. 124A for Narrator and Band (1973) -- 12' Premiere Information: Arkansas Tech Band, Tom Slater, narrator, Gene Witherspoon conducting, February 1, 1974 Bagatelles for Band, Op. 87 (1961) Available From E. F. Kalmus Celebrations, Op. 103 Cantata No. 3, for Chorus and Wind Ensemble (1966) -- 23' Premiere Information: University of Wisconsin Choir, River Falls, WI, Donald Nitz conducting, November 18, 1966 Chorale Prelude: O God Unseen, Op. 160 (1984) -- 8' 30" Premiere Information: East Carolina University Wind Ensemble, Herbert Carter conducting, Winston-Salem, NC, November 4, 1984 Chorale Prelude: So Pure the Star, Op. 91 (1962) -- 4' Premiere Information: Duke University Band, composer conducting, Durham, NC, December 11, 1962 Chorale Prelude: Turn Not Thy Face, Op. 105 -- 4' 30" Premiere Information: Ithaca High School Band, Frank Battisti conducting, May 17, 1967 Divertimento for Band, Op. 42 (1950) -- 11' Premiere Information: Goldman Band, composer conducting, June 16, 1950 Masquerade for Band, Op. 102 (1965) -- 12' Premiere Information: Baldwin-Wallace Conservatory Band, composer conducting, Berea, OH, January 23, 1966 O Cool is the Valley, Op. 118 Poem for Band (1971) -- 6' Premiere Information: Bowling Green Band, OMEA Convention, composer conducting, Columbus, OH, February 5, 1972 Pageant for Band, Op. 59 (1953) Available From Carl Fischer Parable IX, Op. 121 for Band (1972) -- 17' Premiere Information: The Drake University Band, Don R. Marcouiller conducting, Des Moines, IA, April 6, 1973 Psalm for Band, Op. 53 (1952) -- 8' Premiere Information: University of Louisville Band, composer conducting, May 2, 1952 Serenade No. 11, Op. 85 for Band (1960) -- 6' Premiere Information: Ithaca High School Band, composer conducting, Ithaca, NY, April 19, 1961 Symphony for Band, Op. 69 (Symphony No. 6) (1956) -- 16' Premiere Information: Washington University Band, Clark Mitze conducting, St. Louis, MO, April 16, 1956 CHAMBER MUSIC AND SOLO INSTRUMEMTS Concertato, Op. 12 for Piano and String Quartet (1940) Available From New York Public Library Fanfare for Two Trumpets, Op. 164a -- 1' 17" Fantasy, Op. 15 for Violin and Piano (1941) Available From New York Public Library [Note: See more on this piece in the box below!] First String Quartet, Op. 7 (1939) -- 17' Premiere Information: Stuyvesant String Quartet, League of Composers, New York, NY, March 14, 1943 Fourth String Quartet, Op. 122 (Parable X) -- 22' Premiere Information: The Alard String Quartet, Penn State University, February 28, 1973 Infanta Marina, Op. 83 for Viola and Piano (1960) -- 9' Premiere Information: Walter Trampler and Lucy Greene, New York, NY, March 5, 1961 King Lear, Op. 35 Septet for Woodwind Quintet, Timpani and Piano (1948) -- 19' Premiere Information: Martha Graham Company, Montclair, NJ, January 31, 1949 Additional Information: Originally title "The Eye of Anguish" Little Piano Book Arranged for Brass Quintet Little Recorder Book, Op. 70 (1956) -- 9' Premiere Information: Vincent and Lauren Persichetti, Philadelphia, PA, June, 1956 Masques, Op. 99 Ten Pieces for Violin and Piano (1965) Premiere Information: He-Kyong Kim and Joseph Kalickstein, Juilliard School of Music, NY, December 18, 1965 Parable I, Op. 100 for Solo Flute (1965) -- 7' Alto or C Flute Premiere Information: Sophie Sollberger, Philadelphia Art Alliance, Philadelphia, PA, December 16, 1965 Parable II, Op. 108 for Brass Quintet (1968) -- 13' Premiere Information: New York Brass Quintet, Carnegie Recital Hall, NY, April 17, 1968 Parable III, Op. 109 for Solo Oboe (1968) -- 5' 30" Parable IV, Op. 110 for Solo Bassoon (1969) -- 5' 30" Parable V, Op. 112 for Carillon (1969) -- 4' Premiere Information: Albert C. Gerken, Lawrence, KS, May 12, 1970 Parable VII, Op. 119 for Solo Harp (1971) -- 17' Premiere Information: Beth Schwartz, San Diego, CA, June 23, 1972 Parable VIII, Op. 120 for Solo Horn (1972) -- 6' 45" Premiere Information: Priscilla McAfee, Alice Tully Hall, New York, NY, November 7, 1972 Parable XI, Op. 123 for Solo Alto Saxophone (1972) -- 4' 30" Premiere Information: Brian Minor, Kalamazoo, MI, April 14, 1973 Parable XII, Op. 125 for Solo Piccolo (1973) -- 2' 40" Parable XIII, Op. 126 for Solo Clarinet (1973) -- 5' Premiere Information: Esther Lamneck, Paris, France, October 4, 1974 Parable XIV, Op. 127 for Solo Trumpet (1973) -- 4' 20" Parable XV, Op. 128 for Solo English Horn (1973) -- 2' 30" Premiere Information: Paula Dublinski, Tempe, AZ, April 2, 1975 Parable XVI, Op. 130 for Solo Viola (1974) -- 9' Premiere Information: Donald McInnes, International Viola Congress, Ypsilanti, MI, June 29, 1975 Parable XVII, Op. 131 for Solo Doublebass (1974) -- 6' Premiere Information: Bertram Turetzky, Poland, October 1974 [See my Interview with Bertram Turetzky]  Parable XVIII, Op. 133 for Solo Trombone (1975) -- 5' Premiere Information: Per Brevig, Nashville, TN, May 31, 1978 Parable XXI, Op. 140 for Solo Guitar -- 1978 Premiere Information: Peter Segal, Carnegie Recital Hall, NY, October 21, 1978 Parable XXII, Op. 147 for Solo Tuba (1981) Premiere Information: Harvey Phillips, Carnegie Recital Hall, NY, April 25, 1982 [See my Interview with Harvey Phillips] Parable XXIII, Op. 150 for Violin, Cello and Piano (1981) Premiere Information: Hamao Fujiwaro, James Kreger and composer, January 28, 1982 Parable XXV, Op. 164 for Two Trumpets (1986) Pastoral, Op. 21 for Woodwind Quintet Available From G. Schirmer Quintet, Op. 66 for Piano and Strings (1954) -- 23' Premiere Information: Kroll String Quartet and the composer, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, February 4, 1955 Second String Quartet, Op. 24 (1944) -- 18' Premiere Information: Roth String Quartet, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Festival (Blue Network), August 16, 1945 Serenade No. 1, Op. 1 for Ten Wind Instruments (1929) -- 11' Fl., Ob., Cl., Bsn., 2Hn., 2Tpt., Tbn., Tuba Premiere Information: New York Wind Ensemble, San Angelo College, TX, April 21, 1952 Serenade No. 10, Op. 79 for Flute and Harp (1957) -- 20' Premiere Information: Lora and Vito, Istanbul, Turkey, September 21, 1957 Serenade No. 12, Op. 88 for Solo Tuba (1961) -- 5' Premiere Information: Harvey Phillips, Elkhart, IN, November 14, 1962 Serenade No. 13, Op. 95 for Two Clarinets (1963) -- 6' Premiere Information: Chapin School, NYC, May 7, 1964 Serenade No. 14, Op. 159 for Solo Oboe (1984) -- 12' Premiere Information: Pamela Epple, Christ and St. Stephen’s Church, NY, May 17, 1984 Serenade No. 3, Op. 17 for Violin, Cello, and Piano (1941) Available From Southern Music Publishing Co. Serenade No. 4, Op. 28 for Violin and Piano (1945) -- 9' Premiere Information: Peter Oundjian and Charles Abramovic, Tully Hall, NY, November 12, 1981 Serenade No. 6, Op. 44 for Trombone, Viola, and Cello (1950) -- 12' Premiere Information: Davis Shuman, Aaron Chaifetz and Robert Jamieson, Groton, MA, January 27, 1951 Serenade No. 9 for Flute and Alto Flute Serenade No. 9, Op. 71 for Soprano and Alto Recorders (1956) -- 10' Sonata for Solo Cello, Op. 54 (1952) -- 23' Premiere Information: Elsa Hilger, Samaroff Foundation, Museum of Modern Art, NY, May 6, 1953 Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 10 (1940) -- 10' Premiere Information: Broadus Erle, Waldport, OR, November 17, 1945 Suite for Violin and Cello, Op. 9 (1940) Available From New York Public Library Third String Quartet, Op. 81 (1959) -- 20' Premiere Information: Alabama String Quartet, Tuscaloosa, AL, April 19, 1959 Additional Information: Score. Vocalise, Op. 27 for Cello and Piano (1945) -- 3' Premiere Information: Samuel Mayes, Tri-County Concerts, Wayne, PA, November 1, 1946 CHOIR A Clear Midnight from Celebrations, Op. 103 (1966) Part of Celebrations, Op. 103 SATB and Pno. Agnus Dei from Mass, Op. 84 for SATB, a cappella Amens from Hymns and Responses, Op. 68 for SATB Chorus Celebrations, Op. 103 Cantata No. 3 Additional Information: Chorus and Piano transcriptions of "Celebrations, Op. 103 for Chorus and Wind Ensemble." There is That in Me from Celebrations, Op. 103 A Clear Midnight from Celebrations, Op. 103 Sing Me the Universal from Celebrations, Op. 103 I Sing the Body Electric from Celebrations, Op. 103 Stranger from Celebrations, Op. 103 I Celebrate Myself from Celebrations, Op. 103 Four cummings Choruses, Op. 98 for 2-part Mixed, Women’s, or Men’s Voices and Piano (1964) -- 6' Commission Information: Dartmouth Glee Club, Paul Zeller conducting, Hanover, NH, February 12, 1964 Dominic Has a Doll Nouns to Nouns Maggie and Milly and Molly and May Uncles Glad and Very (Five cummings Choruses, Cantata No. 5), Op. 129 for 2-part Mixed, Women’s or Men’s Voices and Piano (1974) -- 11' Commission Information: Huntingdon Choir, Andrew E. Housholder conducting, Huntingdon, NY, December 18, 1974 Gloria from Mass, Op. 84 Hymns and Responses for the Church Year Hymns and Responses for the Church Year Volume 1, Op. 68 (1955) First Presbyterian Church Choir, Philadelphia, Alexander McCurdy conducting, October 7, 1956 Hymns and Responses for the Church Year Volume 2, Op. 166 (1987) I Celebrate Myself from Celebrations, Op. 103 Part of Celebrations, Op. 103 SATB and Pno. I Sing the Body Electric from Celebrations, Op. 103 Part of Celebrations, Op. 103 SATB and Pno. Love, Op. 116 for Women’s Chorus (SSAA), a cappella (1971) -- 4' Premiere Information: Mount Holyoke Singers, Tamara Brooks conducting, 30th Wedding Anniversary at composer’s home, June 3, 1971 Additional Information: Text from Corinthians. Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis, Op. 8 for Mixed Chorus and Piano (1940) -- 7' Premiere Information: Ithaca College Choir, Lawrence Doebler conducting, November 10, 1979 Mass, Op. 84 for Mixed Chorus, a cappella (1960) -- 17' 50" Premiere Information: Collegiate Chorale, Mark Orton conducting, Carnegie Hall, NY, April 20, 1961 Additional Information: Latin text. Proverb, Op. 34 for Mixed Chorus -- 2' Seek the Highest, Op. 78 for SAB Chorus and Piano (1957) -- 4' Premiere Information: Ethical Culture Society Chorus, John DeWitt, conducting, NY, March 17, 1957 Sing Me the Universal from Celebrations, Op. 103 Part of Celebrations, Op. 103 SATB and Pno. Song of Peace, Op. 82 for Male Chorus and Piano (1959) -- 3' Premiere Information: Colgate University Chapel Choir, William Skelton conducting, Hamilton, NY, April 26, 1959 Additional Information: Also available for SATB and Keyboard. Song of Peace, Op. 82a Version for SATB and Keyboard (1959) -- 3' Additional Information: Also available for Male Chorus and Piano. Spring Cantata (Cantata No. 1), Op. 94 for Women’s Chorus and Piano (1963) -- 6' Premiere Information: Wheelock College Choir, Leo Collins conducting, Boston, MA, April 1, 1964 Stranger from Celebrations, Op. 103 Part of Celebrations, Op. 103 SA and Pno. The Pleiades, Op. 107 for Trumpet, SATB Chorus and String Orchestra (1967) -- 23' Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: New York State University College Chorus and Orchestra, Potsdam, NY, composer conducting, May 10, 1968 Additional Information: Text by Walt Whitman There is That in Me from Celebrations, Op. 103 Part of Celebrations, Op. 103 SATB and Pno. Thou Child So Wise for Unison Chorus and Piano Additional Information: Arranged from the version for Vocal Solo Three Canons for Voices, Op. 31 for 3-Part Women’s, Men’s, or Mixed Voices -- 3' 15" Three Selections from Winter Cantata for Women’s Chorus, Flute and Marimba (1964) Two cummings Choruses, Op. 33 for 2-part Mixed, Women’s or Men’s Voices and Piano Available From G. Schirmer Two cummings Choruses, Op. 46 for Women’s Voices, a cappella Available From Carl Fischer Winter Cantata (Cantata No. 2), Op. 97 for Women’s Chorus, Flute, and Marimba (1964) -- 13' 20" Premiere Information: Emma Willard Choir, Russell Locke conducting, Troy, NY, April 9, 1965 HARPSICHORD Eighth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 158 (1984) -- 11' Premiere Information: Linda Kolber, Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, NY, November 15, 1985 Fifth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 152 (1982) -- 9' 30" Premiere Information: John Metz, Tempe, AZ, December 8, 1982 First Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 52 (1951) -- 13' Premiere Information: Fernando Valenti, Town Hall, NY, January 10, 1952 Fourth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 151 (1982) -- 9' 30" Premiere Information: Joan Applegate, Shippensburg State College, Shippensburg, PA, April 3, 1982 Little Harpsichord Book, Op. 155 -- 8' 40" Premiere Information: Elaine Comparone, Philadelphia Art Alliance, Philadelphia, PA, October 16, 1983 Ninth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 163 (1985) -- 13' Premiere Information: Masanobu Ikemiya, Arcady Music Festival, Mt. Desert Island, ME, July 21, 1986 Parable XXIV, Op. 153 for Harpsichord (1982) -- 8' Premiere Information: Cathy Callis, Capital University, Columbus, OH, April 21, 1983 Second Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 146 (1981) -- 11' 30" Premiere Information: Elaine Comparone, Cleveland, OH, June 23, 1982 Serenade No. 15 for Harpsichord, Op. 159 -- 7' 30" Premiere Information: Larry Palmer, Dallas, TX, September 23, 1985 Seventh Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 156 (1983) -- 7' Premiere Information: Barbara Harbach, Wilmot Hall, Rochester, NY, March 19, 1983 Sixth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 154 (1982) -- 7' 30" Premiere Information: Larry Palmer, Christ Church Cathedral, New Orleans, LA, September 11, 1983 Tenth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 167 -- 12' Third Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 149 (1981) -- 9' 17" Premiere Information: Elaine Comparone, Washington, DC, October 10, 1982 OPERAS The Sibyl: A Parable of Chicken Little (Parable XX), Op. 135 Opera in One Act (1976) -- 70' Voices: Soprano, Mezzo-soprano, Alto, Tenor, Baritone, Bass, Mixed Chorus Orch: 2-1-2-1/2-2-2-1; Timp., Perc., Pno. Available from the Presser Rental Library Commission Information: The Pennsylvania Opera Theater Premiere Information: The Pennsylvania Opera Theater, Philadelphia, PA, Barbara Silverstein conducting, April 13, 1985 Additional Information: Libretto by the composer Movements: • Realization • Sky Spell • Wishing ORCHESTRA A Lincoln Address, Op. 124 for Narrator and Orchestra (1972) -- 12' 4-3-4-3; 4-3-3-1; Timp., Perc., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, William Warfield, narrator, Walter Susskind conducting, January 25, 1973 [See my Interview with William Warfield] Concertino for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 16 (1941) -- 9' 2-2-2-2; 2-2-0-0; Timp., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Vincent Persichetti, piano, Eastman-Rochester Symposium Orchestra, Howard Hanson, conductor, October 23, 1945 Concerto for English Horn and String Orchestra, Op. 137 (1977) -- 19' Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: New York Philharmonic, Thomas Stacy, English horn, Erich Leinsdorf, conductor, November 17, 1977 [See my Interviews with Erich Leinsdorf] Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 90 -- 32' 3-2-3-2; 4-3-3-1; Timp., Perc., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Anthony di Bonaventura, piano, Dartmouth Symphony, Mario di Bonaventura conducting, Hanover, NH, August 2, 1964 Dance Overture, Op. 20 (1942) -- 8' 3-3-3-3; 4-4-3-1; Timp., Perc, Pno., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Tokyo Symphony Orchestra, Konoye conducting, Japan, February 7, 1948 Fables for Narrator and Orchestra, Op. 23 (1943) Available From Carl Fischer Fairy Tale, Op. 48 (1950) Available From Carl Fischer Flower Songs (Cantata No. 6), Op. 157 for Mixed Chorus and String Orchestra (1983) -- 21' Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: The Philadelphia Singers with the Concerto Soloists, Michael Korn conducting, Academy of Music, Philadelphia, April 20, 1984 Additional Information: Text by e.e. cummings Introit for Strings, Op. 96 (1964) -- 3' Premiere Information: Youth Symphony of Kansas City, Jack Herriman conducting, MO, May 1, 1965 Night Dances, Op. 114 (1970) -- 22' 3-3-2-2; 4-3-3-1; Timp., Perc., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: NYSSMA Orchestra, Kiamesha Lake, New York, Frederick Fennell conducting, December 9, 1970 [See my Interview with Frederick Fennell] Serenade No. 5, Op. 43 (1950) -- 11' 2-2-2-2; 4-2-3-1; Timp., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Louisville Orchestra, Robert Whitney conducting, November 15, 1950 Sinfonia: Janiculum, Op. 113 (Symphony No. 9) -- 23' 4-3-4-3; 4-3-3-1; Timp., 2Perc., Hp., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, conductor, March 5, 1971 Stabat Mater, Op. 92 for Chorus and Orchestra (1963) -- 28' 2-2-2-2; 4-2-3-1; Timp. Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Collegiate Chorale, Abraham Kaplan conducting, Carnegie Hall, NY, May 1, 1964 Symphony for Strings, Op. 61 (Symphony No. 5) (1953) -- 22' Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Louisville Orchestra, Whitney conducting, August 28, 1954 Symphony No. 1, Op. 18 (1942) 2-3-2-3; 7-3-3-1; Timp., B.Dr., Str. Withdrawn Symphony No. 2, Op. 19 (1942) 2-3-2-3; 4-2-2-0; Timp., Pno., Str. Withdrawn Symphony No. 3, Op. 30 (1946) -- 28' 3-3-3-3; 7-3-3-1; Timp., Perc., Pno., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy conducting, November 21, 1947 Symphony No. 4, Op. 51 (1951) -- 23' 3-3-3-2; 4-2-3-1; Timp., Perc., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, conductor, December 17, 1954 Symphony No. 7, Op. 80 (Liturgical) (1958) -- 25' 4-3-4-3; 4-3-3-1; Timp., Perc., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: St. Louis Symphony, Remoortel conducting, October 24, 1959 Symphony No. 8, Op. 106 (1967) -- 29' 3-3-3-2; 7-3-3-1; Timp., Perc., Hp., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Baldwin Wallace Conservatory Orchestra, George Poinar conducting, October 29, 1967 Te Deum, Op. 93 for Chorus and Orchestra (1963) -- 14' 2-2-2-2; 4-2-3-1; Timp., Perc., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Pennsylvania All-State Chorus, Allen Flock conducting, Philadelphia, PA, March 15, 1964 The Creation, Op. 111 for SATB Soli, Chorus and Orchestra -- 70' 3-3-3-2; 4-3-3-1; Timp., Perc., Str. Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Juilliard Chorus and Orchestra, composer conducting, Tully Hall, NY, April 17, 1970 Additional Information: Text by the composer from mythological, scientific, poetic and Biblical sources. The Hollow Men, Op. 25 for Trumpet and String Orchestra -- 8' Available from the Presser Rental Library Premiere Information: Germantown Symphony Orchestra, Arthur Lipkin conducting, December 12, 1946 Additional Information: Also available for Trumpet and Piano or Organ ORGAN Auden Variations, Op. 136 (1977) -- 22' Premiere Information: Leonard Raver, International Contemporary Organ Music Festival, Hartford, CT, July 14, 1978 Chorale Prelude: Drop, Drop, Slow Tears, Op. 104 -- 12' Premiere Information: Haskill Thomson, Lexington, KY, April 13, 1967 Chorale Prelude: Give Peace, O God, Op. 162 -- 12' Premiere Information: Donald Williams, American Guild of Organists National Convention, Ann Arbor, MI, June 3, 1986 Do Not Go Gentle, Op. 132 for Pedals Alone -- 8' Premiere Information: Leonard Raver, Boston, MA, November 18, 1974 Dryden Liturgical Suite, Op. 144 (1980) -- 18' Premiere Information: Marilyn Mason, American Guild of Organists National Convention, St. Paul, MN, June 18, 1980 Parable VI, Op. 117 (1971) -- 14' Premiere Information: David Craighead, American Guild of Organists National Convention, Forth Worth, TX, June 21, 1972 Shimah B’Koli (Psalm 130), Op. 89 (1962) -- 10' Premiere Information: Virgil Fox, Philharmonic Hall, NY, December 15, 1962 Sonata for Organ, Op. 86 (1960) -- 12' Premiere Information: Rudolph Kremer, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, December 28, 1960 Sonatine for Organ, Pedals Alone, Op. 11 (1940) -- 7' Premiere Information: Vincent Persichetti, Arch Street Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, PA, November 8, 1940 Song of David, Op. 148 (1981) -- 5' 30" Premiere Information: Leonard Raver, Church of the Ascension, New York, NY, March 7, 1983 PIANO Appalachian Christmas Carols (After John Jacob Niles) for One Piano, Four Hands -- 7' 30" Concerto for Piano, Four Hands, Op. 56 -- 18' Premiere Information: Vincent and Dorothea Persichetti, Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival, November 29, 1952 Eighth Piano Sonata, Op. 41 (1950) -- 7' Premiere Information: Claire Shapiro, Philadelphia Conservatory, Philadelphia, PA, March 19, 1956 Fifth Piano Sonata, Op. 37 (1949) -- 8' 30" Premiere Information: Jean Geis, Town Hall, NY, March 11, 1951 First Piano Sonata, Op. 3 (1939) -- 16' Premiere Information: Vincent Persichetti, Philadelphia Conservatory, Philadelphia, PA, May 8, 1939 Four Arabesques, Op. 141 (1978) -- 3' 20" Fourth Piano Sonata, Op. 36 (1949) -- 18' 30" Premiere Information: Vincent Persichetti, League of Composers, NY, December 27, 1949 Little Mirror Book, Op. 139 (1978) -- 4' 30" Little Piano Book, Op. 60 (1953) -- 9' Premiere Information: Lauren Persichetti, Philadelphia Conservatory, November 14, 1954 Mirror Etudes, Op. 143 (1979) -- 14' Premiere Information: Virginia Sircy, Lawton, OK, June 21, 1980 Ninth Piano Sonata, Op. 58 (1952) -- 12' Premiere Information: David Burge, Madison, WI, March 8, 1962 Organ Prelude and Fugue in A Minor (Johannes Brahms) Parable XIX, Op. 134 for Piano (1975) -- 10' 30" Premiere Information: Daniel Pollack, MTNA National Convention, Dallas, TX, March 30, 1976 Parades, Op. 57 (1952) -- 3' Premiere Information: Garth Persichetti, Philadelphia Conservatory, Philadelphia, PA, February 5, 1956 Piano Sonatinas, Volume 1 -- 12' total Premiere Information: Sonatina No. 2: Margaret Barthel, Town Hall, NY, December 13, 1951 Movements: • Sonatina No. 1, Op. 38 (1950) (3min.) • Sonatina No. 2, Op. 45 (1950) (5min.) • Sonatina No. 3, Op. 47 (1950) (4min.) Piano Sonatinas, Volume 2 -- 9' total Movements: • Sonatina No. 4, Op. 63 (1954) (3min.) • Sonatina No. 5, Op. 64 (1954) (3min.) • Sonatina No. 6, Op. 65 (1954) (3min.) Poems for Piano, Volume 1, Op. 4 (1939) -- 9' Premiere Information: Vincent Persichetti, League of Composers (CBS), February 24, 1940 Poems for Piano, Volume 2, Op. 5 (1939) -- 9' Premiere Information: Vincent Persichetti, WNYC Festival of American Music, February 13, 1945 Poems for Piano, Volume 3, Op. 14 (1941) -- 10' Reflective Keyboard Studies, Op. 138 (1978) Second Piano Sonata, Op. 6 (1939) -- 11' Premiere Information: Dorothea Flanagan, El Dorado, KS, January 8, 1941 Serenade No. 2, Op. 2 (1929) -- 4' Premiere Information: Vincent Persichetti, Combs Conservatory, Philadelphia, PA, December 21, 1929 Serenade No. 7, Op. 55 (1952) -- 9' Serenade No. 8, Op. 62 for Piano, 4 Hands (1954) -- 3' Seventh Piano Sonata, Op. 40 (1950) -- 7' Premiere Information: Robert Smith, Philadelphia Conservatory, Philadelphia, PA, May 21, 1956 Sixth Piano Sonata, Op. 39 (1950) -- 12' Premiere Information: Joseph Bloch, Town Hall, NY, April 26, 1951 Sonata for Two Pianos, Op. 13 (1940) -- 11' 17" Premiere Information: Dorothea Flanagan and Vincent Persichetti, Town Hall, New York, April 2, 1941 Sonatas for Piano Complete Edition Additional Information: Sonatas 1-12 also available separately. Tenth Piano Sonata, Op. 67 (1955) -- 22' Premiere Information: Josef Raieff, Juilliard School of Music, NY, February 20, 1956 Third Piano Sonata, Op. 22 (1943) -- 12' 30" Premiere Information: Vincent Persichetti, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Festival, August 13, 1943 Three Toccatinas, Op. 142 (1979) -- 6' Premiere Information: International Piano Festival and Competition, University of Maryland, June 18, 1980 Twelfth Piano Sonata (Mirror Sonata), Op. 145 (1981) -- 13' Premiere Information: Jeffrey Jacob, Notre Dame, IN, April 18, 1983 Variations for an Album, Op. 32 (1947) -- 4' Premiere Information: John Kirkpatrick, Baldwin-Wallace College, October 17, 1947 Winter Solstice, Op. 165 (1986) -- 11' VOCAL COMPOSITIONS A Net of Fireflies, Op. 115 Cycle of 17 Songs for Voice and Piano (1970) -- 19' Premiere Information: Carolyn Reyer, Tully Hall, NY, May 12, 1971 Additional Information: Haiku verse, translated by Harold Stewart. Carl Sandburg Songs, Op. 73 (1957) Available From New York Public Library e. e. cummings Songs, Op. 26 (1945) Available From New York Public Library Emily Dickinson Songs, Op. 77 (1957) Premiere Information: Shirley Verrett, Town Hall, NY, November 4, 1958 Out of the Morning I'm Nobody When the Hills Do The Grass English Songs, Op. 49 (1951) Available From New York Public Library Harmonium, Op. 50 Cycle for Soprano and Piano (1951) -- 65' Premiere Information: Hilda Rainer and Vincent Persichetti, League of Composers, Museum of Modern Art, NY, January 20, 1952 Additional Information: Poems by Wallace Stevens Hilaire Belloc Songs, Op. 75 (1957) Thou Child So Wise additional Information: Also available for Unison Chorus and Piano The Microbe James Joyce Songs, Op. 74 (1957) Premiere Information: Marlene Kleinman and Dorothea Persichetti, Philadelphia, PA Unquiet Heart Brigid's Song Noise of Waters Robert Frost Songs, Op. 76 (1957) Available From New York Public Library Sara Teasdale Songs, Op. 72 (1957) Available From New York Public Library Two Chinese Songs, Op. 29 (1945) -- 1' 20" Premiere Information: Richard Harvey, Town Hall, NY, April 13, 1948 Movements: • All Alone • These Days -- Taken from the Vincent

Persichetti Music Association website, with links added for this

presentation.

|

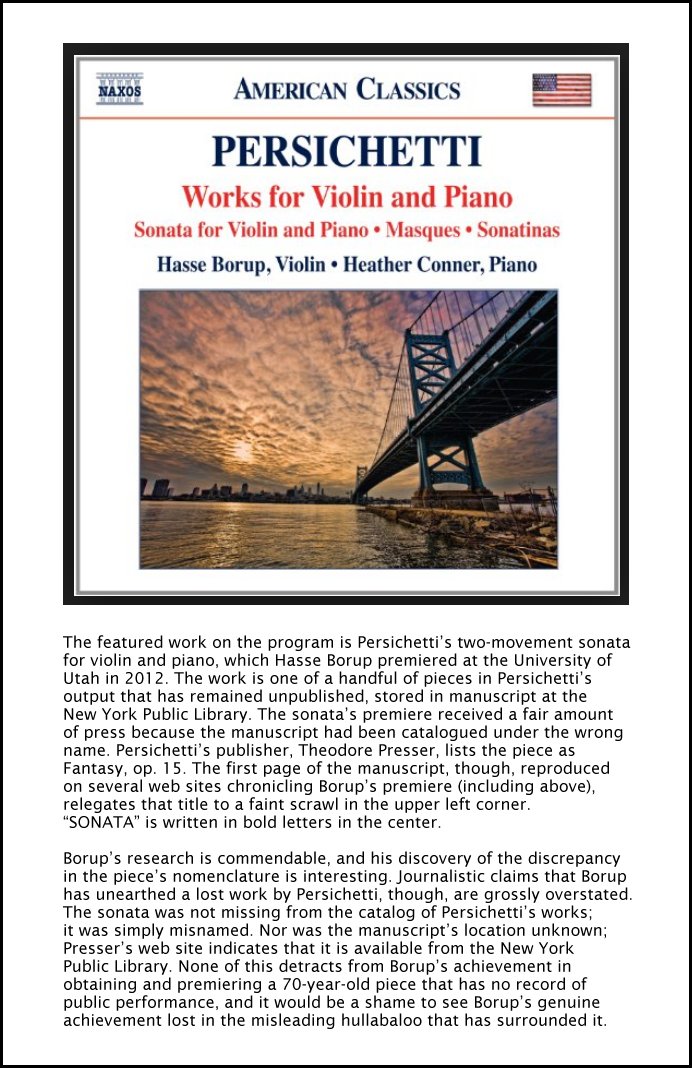

August 30, 2012 Violinist found—and will premiere—lost

sonata of Vincent Persichetti

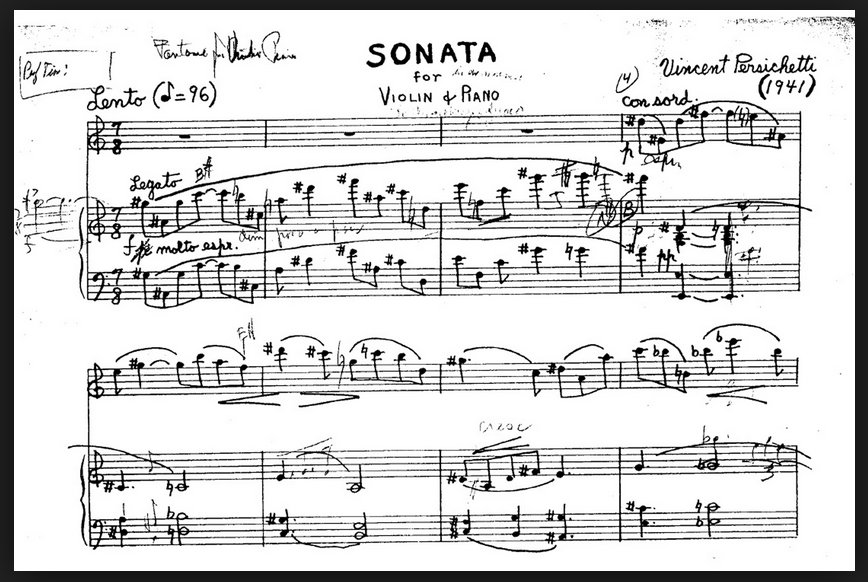

(Phys.org)—A University of Utah violinist has made a once-in-a-career music discovery in a story that hints of Indiana Jones. Hasse Borup, who is associate professor and head of string and chamber music studies at the U's School of Music, has uncovered a lost, 70-year old sonata by American composer Vincent Persichetti (1915-1987). The piece, "Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano," was composed in 1941 and has never been heard in public. In fact, until Borup retrieved it in 2010, it had languished for decades in the storage archives of the New York Public Library. Now, Borup will perform the sonata in a world premiere with Heather Conner, associate professor of piano at the U. The premiere will be Sunday, September 30, 2012 at 7:00 p.m. – part of the free "Sundays@7" faculty concert series – in Libby Gardner Hall on campus in Salt Lake City. A prelude to the concert will be a free, public lecture by Michael Chikinda on the sonata and Persichetti's repertoire. Chikinda is assistant professor of music theory at the U and has done extensive additional research on the project. The "Fridays with Faculty" lecture will be held Friday, September 28, 2012 at 12:00 noon in the Thompson Chamber Music Hall on campus. "Persichetti is a much-neglected American composer," says Chikinda. "Through the talk and performance, listeners will have a rare opportunity to learn about Persichetti's life, his work, and where this piece fits within not only his oeuvre, but the canon of 20th century Art Music." Borup continues, "It is extremely unusual—perhaps as rare as a total solar eclipse—to find a piece of music that has never been played. And it is particularly gratifying for a performer to be able to play something altogether new." In addition to September's premiere, the piece will be recorded at the U in October as part of a project to record Persichetti's complete repertoire for violin and piano, highly important compositions for the genre. Chikinda will write the liner notes for the CD. "Persichetti's music was well regarded and widely performed by his contemporaries, but a surprising number of his works remain unrecorded," says Borup. "I hope our work helps to elevate his important contributions as an influential composer and remarkable educator." The recordings are being made for the classical label, Naxos, and made possible with a University of Utah Creative Research Grant. The Discovery The hunt started when Borup began looking for music to expand the catalog of recorded American violin works. He planned a recording to follow his "American Fantasies," which featured works for violin and piano by Arnold Schoenberg and his students. Borup came upon the catalog of Persichetti, whose work fit the profile that Borup and the label were looking for. Even better, it was the right amount of music for a CD [see image of booklet cover and press info below].  [Scan of the original hand written score of

the "Sonata No.1 for Violin and Piano" by Vincent Persichetti (1941).

Photo: Courtesy of the University of Utah School of Music.] Borup began comparing lists from Persichetti's publisher and from the New York Public Library of Performing Arts, which holds the musical estate of the composer. During his research, he uncovered a discrepancy in the descriptions of the composer's inventory. Often, unless a librarian systematically catalogs pieces of music, a composer's inventories can be somewhat disordered, with names and numbers not lining up perfectly. But after a fair amount of detective work on his part, Borup deduced that there was a work in the library's catalog with a name that didn't appear elsewhere. Borup then had to gain permission of the composer's daughter, Lauren Persichetti, to sort through the works stored at the Library. She readily agreed, and several music librarians picked up the scent and set out to track down the missing piece. After some months, the trail led to a library storage archive in New Jersey. The sheet music was finally extracted, scanned and emailed to a thrilled Borup. However, the detective work wouldn't end there. "As soon as I saw the score, I realized it was unusable in its current form," Borup relates. "It was handwritten, with notes and scribbles that were impossible to ascribe, and I knew that there was still significant work to be done before it could be played." Research and Preparing to Perform the Music Enter undergraduate composition student Dexter Drysdale. With a grant from the University of Utah's Undergraduate Research Program, Drysdale was able to complete student research in support of the main project, spending nearly two semesters to create what is called a "critical edition" of the sonata. Importantly, the manuscript Borup discovered was a complete piece, but far from finished. It was covered in "all these little optional notes written in hand on the edges of the paper," Drysdale notes. "It was like trying to break a code." And deciphering the handwriting was a distinct challenge. The sonata is one of Persichetti's earlier works, written before his better-known compositions. "So it was probably written in the same manner I write and work as a student—full of questions," says Drysdale. Once he figured out that the sonata was a twelve-tone piece, he could rely on the rules of that structure to decide about pitches and even chords. Using the music composition and notation software held a special perk for Drysdale, "I typed out the piece as I went and used the playback feature—which means I was one of the first people to hear that piece since Perischetti created it." Borup notes that "Dexter's knowledge of the instruments and the process of composing music helped put forth editorial decisions about the piece, which were then vetted by several sets of musicians' eyes." "It has been a unique and incredibly valuable experience for all of us to work on material of this significance," says Borup. "The finished product showcases an important period of his development as a composer. Each of the movements of the solo sonata explores the vast range of tone colors and special effects available on the instrument, but the virtuosic writing never over-shadows the serene simplicity of the musical structure. Best of all, the music world now has a playable score of a piece that reflects what Persichetti had in mind in 1941," he concludes.  |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on November 15,

1986. Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1990,

1995 and 2000. An audio copy was placed in the Oral History

American Music Archive at Yale University. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2009. At the end of 2014, the text of the interview

was very slightly edited, the two boxes about his published works (at

the bottom) were added, as well as several images and links.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award-winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.