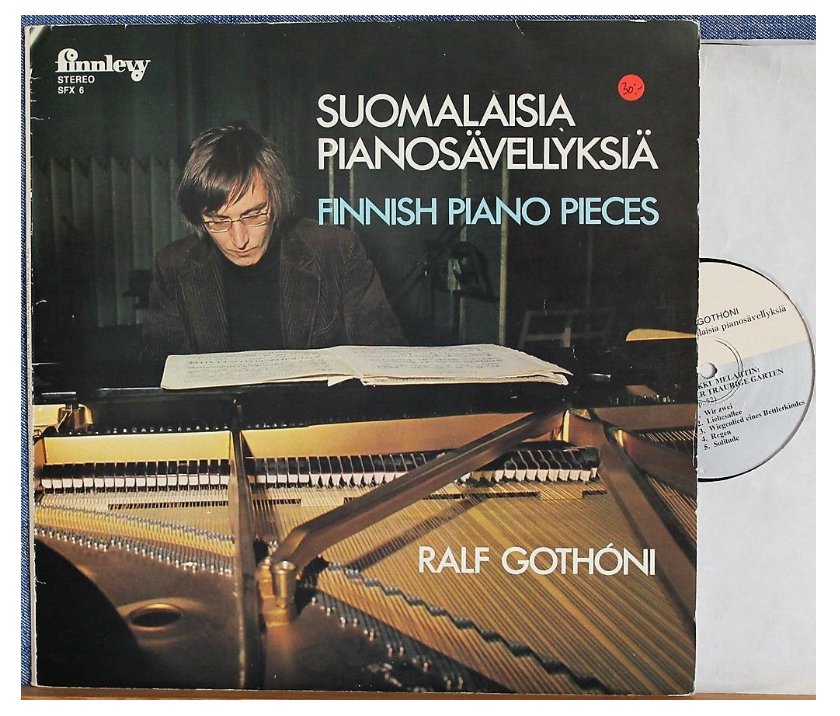

| Ralf Gothóni (born May 2, 1946

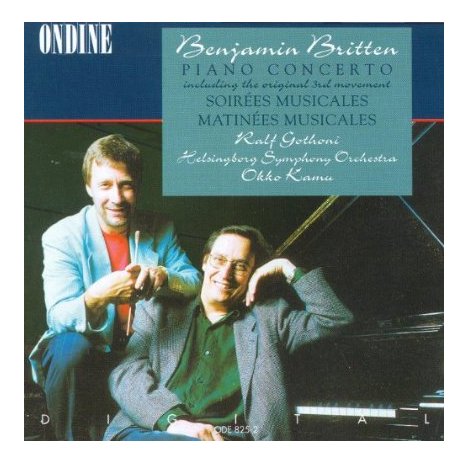

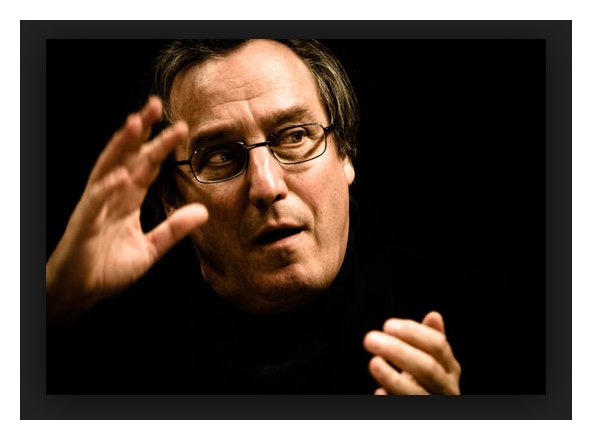

in Finland, now living in Germany) has a multifaceted career as solo pianist,

chamber musician and conductor throughout the world. He is known for his

unconventional music-making, not just as a pianist, but as a musician with

a remarkable philosophy about music and the wholeness of musicianship. Gothóni began his studies on the violin at age three and on piano at age five. At fifteen he made his debut as an orchestra soloist and in 1967 was named “debut of the year” at the Jyväskylä Summer Festival He has performed at the most prestigious music festivals – Salzburg, Berlin, Prague, Prades, Aldeburgh, Edinburgh, La Roque de Antheron, Ravinia, Tanglewood – and with many of the world’s leading orchestras: the Chicago Symphon, Detroit Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Berlin Philharmonic, Warsaw Philharmonic, the Bavarian Radio Symphony, the Japan Philharmonic and the English Chamber Orchestra among many others. He appears regularly in concerts both as conductor and soloist, frequently conducting from the keyboard. Ralf Gothóni has premiered more than a dozen piano concertos by such noted composers as Sir John Tavener, Aulis Sallinen, C. Curtis-Smith, Einojuhani Rautavaara and Srul Irving Glick. A noted musical collaborator, he is also a frequent guest artist at the major international chamber music festivals. Mr. Gothóni has some one hundred recordings on numerous labels, including BIS, CPO, Decca, DGG, EMI and Ondine, with whom he has produced more than twenty CDs. Of particular note are his Schubert interpretations, the piano concertos of Benjamin Britten, Villa-Lobos and Rautavaara. In recent years he has recorded several CD:s with music by Alfred Schnittke and Aulis Sallinen, both as soloist and conductor. Ralf Gothóni was Principal Conductor of the legendary English Chamber Orchestra from 2000-09. From 2001–06 he was Music Director of the Northwest Chamber Orchestra in Seattle. In 2004 he was named Guest Conductor of Deutsche Kammerakademie. He has held many other artistic postitions: Chief Conductor of the Finlandia Sinfonietta (1989–94), Principal Guest Conductor of the Turku Philharmonic (1995–2000), Artistic Director of the famous Savonlinna Opera Festival (1984–1987), Founder of the “Forbidden City Music Festival” in Beijing and its Artistic Director in 1996 and 1998, and Founder of “Musical Bridge Egypt-Finland,” a cultural collaboration between Finland and Egypt where his northern colleagues perform with Egyptian musicians. Since 2009 he has been Artistic Advisor for the Springlight Music Festival in Helsinki. He has also supported classical music in Israel and in South Africa. Contact with young musicians is very close to his heart. He is the Artistic Chairman of “Savonlinna Music Academy,” a summer institute for chamber music, Lied and opera. He has held the position of Professor at the Hochschule für Musik in Hamburg (1986–96), the Hanns Eisler Hochschule in Berlin (1996–2000) and the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki 1992–2007. In May, 2000 he was appointed Visiting Professor at the Royal College of Music in London and in 2010, the Musikhochschule Detmold. In 2006 he became head of the piano chamber music department at the “Instituto de Musica Camara, Reina Sofia” in Madrid. Besides giving master classes around the world, he has spent many summers as a faculty member at the Steans Institute for Young Artists at Ravinia in Chicago. In recent years he has served as juror at major international piano competitions. A composer of some note, Ralf Gothóni has written three chamber operas, chamber music, songs and the chamber cantata, The Ox and its Sephard (recorded by Ondine), as well as a Concerto Grosso version of this for violin, piano and strings. This concerto was premiered in1999 with the composer as piano soloist and conductor and his wife, Elina Vähälä as violin soloist. In April 2003 his chamber orchestra arrangement of Hugo Wolf´s Italian Songbook was premiered in Stuttgart. His first book, The Creative Moment, was published with great success in 1998. A second book, Does the Moon Rotate, was published in 2001. Mr. Gothóni has been honored with numerous awards and distinctions including the Gilmore Artist Award in 1994, one of the major awards in classical music, the Schubert Medal of the Austrian Ministry of Culture and the Order of Pro Finlandia. -- From the California Artists

Management website, June, 2011

|

RG: In the last century

— until 1850, ’60, ’70 — all the composers

were interpreters at the same time. It was the same person. Both

things were in one person. Then suddenly, this century separated, somehow,

the whole thing and made stars of interpreters — which

is the second level of music-making. I mean, to interpret music is

just the secondary thing. The first thing is, of course, to create it.

There are very few composers who really are able to play an instrument well

nowadays, and also very few instrumentalists who are able to compose.

So that’s why it’s very important to try to find a synthesis between these

things, and then notice that they both help each other. One could say

they’re both personalities in one. Of course there have been very great

musicians which have done both. Liszt interpreted his works to an incredible

degree, and the whole aspect of how he played piano with absolute power;

and of course, many, many others.

RG: In the last century

— until 1850, ’60, ’70 — all the composers

were interpreters at the same time. It was the same person. Both

things were in one person. Then suddenly, this century separated, somehow,

the whole thing and made stars of interpreters — which

is the second level of music-making. I mean, to interpret music is

just the secondary thing. The first thing is, of course, to create it.

There are very few composers who really are able to play an instrument well

nowadays, and also very few instrumentalists who are able to compose.

So that’s why it’s very important to try to find a synthesis between these

things, and then notice that they both help each other. One could say

they’re both personalities in one. Of course there have been very great

musicians which have done both. Liszt interpreted his works to an incredible

degree, and the whole aspect of how he played piano with absolute power;

and of course, many, many others.

RG: Oh, it depends. Every pianist has a kind

of character of the instrument which he likes mostly. It also depends

a little bit on pieces. For Brahms, one needs a rather heavier character

of the piano because it’s easier to play Brahms with resistance than without

it. Then, of course, Mozart or Schubert are very much with a light

character on the action. Then I like very much a rather soft tone,

soft intonation, to be able to work with the piano. If the intonation

is very hard, very stoney, you can’t play anything because everything is

coming too directly out of. That makes you feel very intense.

But when the piano is softer, then you can do more.

RG: Oh, it depends. Every pianist has a kind

of character of the instrument which he likes mostly. It also depends

a little bit on pieces. For Brahms, one needs a rather heavier character

of the piano because it’s easier to play Brahms with resistance than without

it. Then, of course, Mozart or Schubert are very much with a light

character on the action. Then I like very much a rather soft tone,

soft intonation, to be able to work with the piano. If the intonation

is very hard, very stoney, you can’t play anything because everything is

coming too directly out of. That makes you feel very intense.

But when the piano is softer, then you can do more. RG: No. No, it’s very often interesting

to notice that those aspects you feel are important in a concert hall do not

come through on recordings, because the recording is just for the ear and

the concert is for everything, for eyes and ear. So when we talk about

the wholeness of our music-making — that the whole

body should make the music and feel the music — that

belongs to the stage. But the consciousness of musical lines, musical

rhythms, harmonies, what is happening, the structure, the full control of

our musical laws, they belong to the recording. The interpretation

is always the main thing, of course. The technical control is the problem

of the producer.

RG: No. No, it’s very often interesting

to notice that those aspects you feel are important in a concert hall do not

come through on recordings, because the recording is just for the ear and

the concert is for everything, for eyes and ear. So when we talk about

the wholeness of our music-making — that the whole

body should make the music and feel the music — that

belongs to the stage. But the consciousness of musical lines, musical

rhythms, harmonies, what is happening, the structure, the full control of

our musical laws, they belong to the recording. The interpretation

is always the main thing, of course. The technical control is the problem

of the producer. RG: No, no, no. There are tours, especially

here in the United States now, so you have to travel every second day, and

play again the next day. But it’s very hard, and it is also very dangerous

because this kind of life makes it very easily to become routine. You

have to keep yourself in condition, and then keeping your mind working perfectly

means that you must be sure about what you are doing during the tour with

your music. And to be sure about what you are doing makes what you

are doing very often the same twice and the third time and the fourth time

also. Then little by little you fall down in a kind of rut. [Laughs]

RG: No, no, no. There are tours, especially

here in the United States now, so you have to travel every second day, and

play again the next day. But it’s very hard, and it is also very dangerous

because this kind of life makes it very easily to become routine. You

have to keep yourself in condition, and then keeping your mind working perfectly

means that you must be sure about what you are doing during the tour with

your music. And to be sure about what you are doing makes what you

are doing very often the same twice and the third time and the fourth time

also. Then little by little you fall down in a kind of rut. [Laughs]

This interview was recorded in a rehearsal room backstage at the

Ravinia Festival in Highland Park, IL, on June 30, 1995. Segments were

used (with recordings) on WNIB the following year, and on WNUR in 2003.

The transcription was made and posted on this website in 2014.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.