|

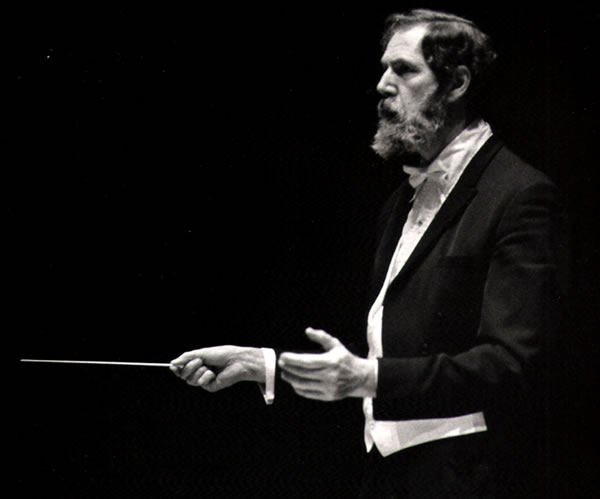

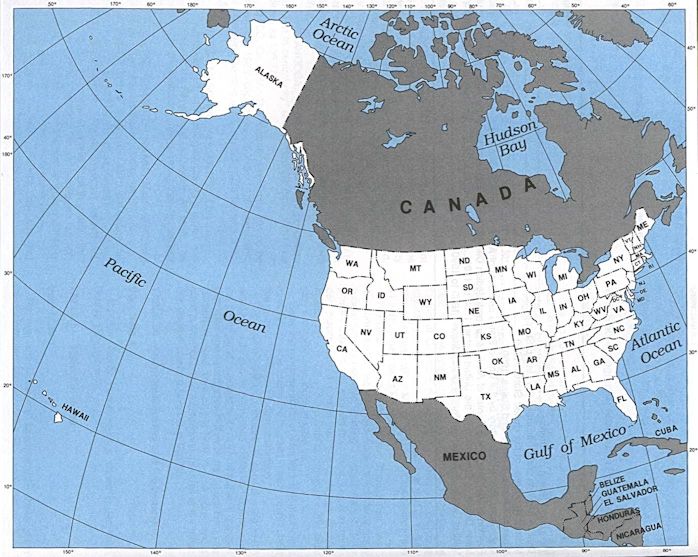

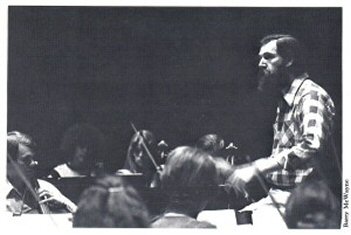

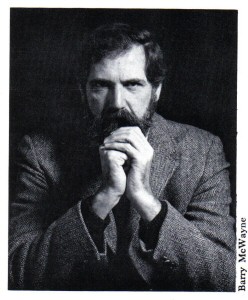

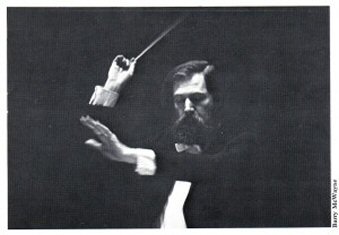

Conductor Gordon Wright

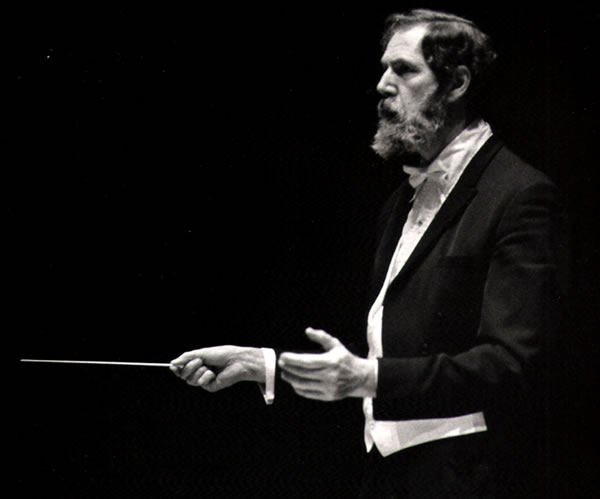

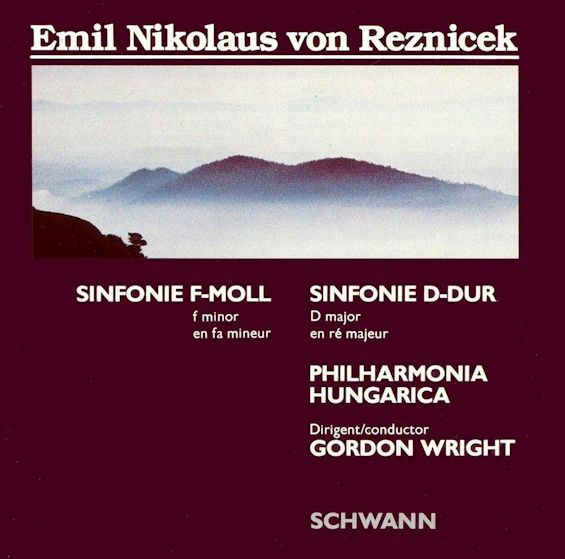

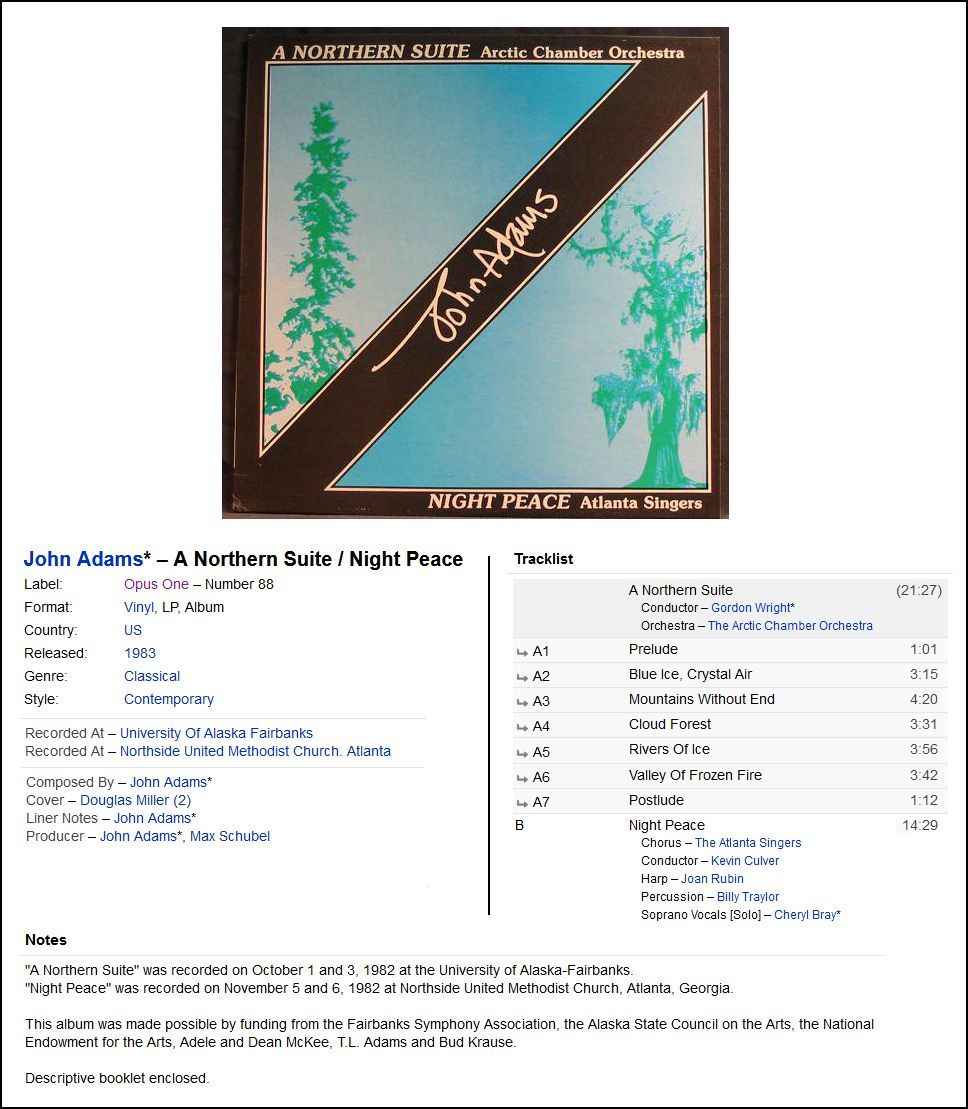

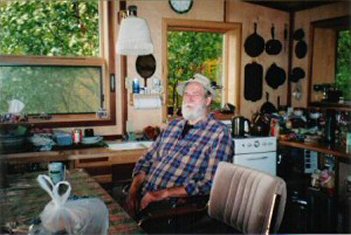

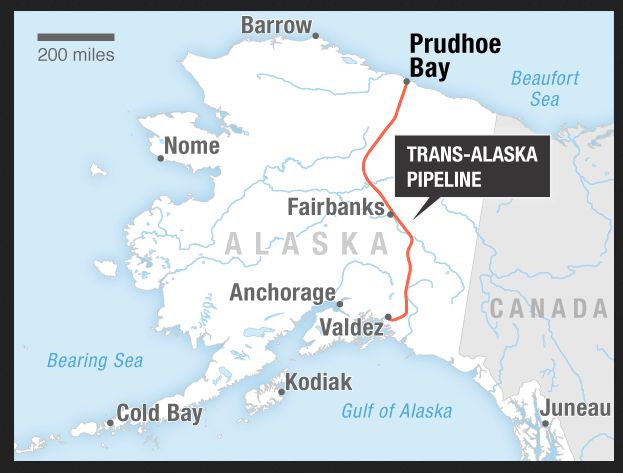

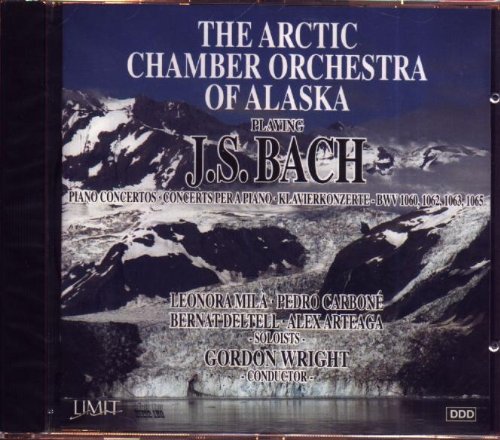

Born: December 31, 1934 - Brooklyn, New York, USA Died: February 14, 2007 - Indian, Alaska, USA The American conductor, Gordon Wright, attended the College of Wooster in Ohio. He received a master's degree from the University of Wisconsin, where he started a chamber orchestra and ran an antiquarian music bookstore. He went on to study in Berlin and in Salzburg, Austria. In 1960 Gordon Wright founded the Madison Summer Symphony (which became the Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra), and presented nine seasons of summer concerts. Early in his career, Gordon Wright became fascinated with the music of Emil Nikolaus von Reznicek (1860-1945), a prolific late-Romantic German composer generally forgotten except for his effervescent Donna Diana Overture. That piece was used as the theme for the radio and television versions of Sergeant Preston of the Yukon, about the adventures of a Mountie. Wright said listening to the radio show had piqued his interest in Reznicek's other works, and he began hunting down and performing his music. This led to his creation of the Reznicek Society, which was dedicated to promoting worthy but lesser-known composers. “If he could write a theme like that, I said to myself, how did his other music shape up?” Wright said in a 1990 interview with The New York Times. “So over the years I began to track down all of his scores I could find.” Gordon Wright went to Alaska in 1969 as music director of the Fairbanks Symphony Orchestra. In 1989, he left that position and retired as a professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. In his 20 year tenure as conductor of the Fairbanks Symphony Orchestra he developed it into a polished ensemble performing full seasons of major symphonic works. In 1970 he founded the Arctic Chamber Orchestra (ACO), an offshoot of the symphony, touring annually to the farthest reaches of Alaska and the Yukon. He took the on tour to remote and musically bereft towns throughout the state, traveling on school buses, boats, seaplanes and even dog sleds. Concert dress sometimes included parkas. He conducted in Barrow, deep inside the Arctic Circle, and in Key West, Florida. Inga-Lisa Wright said he might have been the only person to lead performances in both the northernmost and southernmost locales in the country. The ACO also toured in Europe, The People's Republic of China and Spain.The tours were an ambitious Alaskan adventure, making great music while exploring the diverse cultures and vast expanses of Alaska; as well as other parts of the world, no matter how difficult the logistics of moving an orchestra around in remote areas of the bush or half way around the world. Gordon always insisted that the touring was intended to "share the music" without imposing a message. Gordon Wright conducted orchestras in Germany, England, Holland, Norway, and Bulgaria. He also conducted orchestras in Anchorage, Minneapolis, Chicago, Washington state, Montana, and Idaho among others. He conducted three concerts in Town Hall in New York City with the Orchestra of St. Luke’s presenting the nearly forgotten music of Reznicek. He became the Principal Guest conductor of the Keys Chamber Orchestra in 2003 presenting consecutive spring concerts in the Florida Keys. Gordon was equally at home on a podium in a concert hall, or in his rustic cabin in the wilderness. His passion for Alaska carried over to environmental activism. Gordon spearheaded the founding of the Fairbanks Environmental Center in 1971, now known as the Northern Alaska Environmental Center. His love for Alaska's wilds was a major theme in his life. The bearded Gordon Wright, who stood 6-feet, 6-inches tall, was also a hardy outdoorsman who camped, hiked and kayaked in the Alaskan wilds, sometimes in the company of bears. He was one of Alaska's best-known and beloved musicians. His many friendships and contributions were carried on with pervasive humor and well known philosophical irony. Radio and TV notables such as Tom Brokaw, Charles Kurault, Garrison Keillor and Michael Feldman found his story compelling, and interviewed him in live national broadcasts. Gordon's impact on music and on people is truly enormous. Gordon's recordings include his own music and other contemporary Alaskan composers. He and the ACO twice received the Governors Award for the Arts and a commendation from the Alaska Legislature. Gordon Wright was found dead February 14, 2007 on the porch of his cabin in Indian, Alaska. He was 72. His body was discovered after he failed to arrive at Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport to pick up a composer, said his former wife, Inga-Lisa Wright. The cause of death had not been immediately determined, she said. He is survived by his daughter, Karin Sturla; two sons, Charles and Daniel; five grandchildren, and brother Harry Wright. The Anchorage Daily News said Wright's body was removed from his cabin by friends and state troopers in a pine coffin that he had bought years ago and used as a storage bench. -- Biography slightly edited from the Bach

Cantatas Website

|

BD: You say you push the audience. Do you push

yourself as well, in terms of growing?

BD: You say you push the audience. Do you push

yourself as well, in terms of growing? BD: How big is it now?

BD: How big is it now?

Challenge of the Yukon is an American radio adventure series that began on Detroit's WXYZ, and is an example of a Northern genre story. The series was first heard on January 3, 1939. The title changed to Sergeant Preston of the Yukon in September 1950, and remained under that name through the end of the series and into television. Challenge of the Yukon began as a 15-minute serial, airing locally until May 28, 1947. Shortly thereafter, the program acquired a sponsor, Quaker Oats, and the series, in a half-hour format, moved to the networks. The program aired on ABC from June 12, 1947, to December 30, 1949. It was then heard on The Mutual Broadcasting System from January 2, 1950, through the final broadcast on June 9, 1955. In September 1950, when the show moved to three broadcasts a week, the title was changed to Sergeant Preston of the Yukon. The program was an adventure series about Sergeant Frank Preston of the North-West Mounted Police and his lead sled dog, Yukon King, as they fought evildoers in the Northern wilderness during the Gold Rush of the 1890s. In January 1951, the radio version was resurrected, running until 1955, when the show moved once again to television through 1958 as Sergeant Preston of the Yukon. From 1951 to 1958, Dell Comics published 29 issues of Sergeant Preston of the Yukon. The first four issues appeared biannually, then quarterly, in the weekly catch-all series Four Color Comics (#344, 373, 397, 419), then assumed its own numbering with issue #5, most often as a quarterly but also bimonthly. Just as the William Tell Overture was certainly going through the minds of readers of The Lone Ranger items which appeared in print, we can assume that the Donna Diana Overture resonated with many young and old readers of the Sergeant Preston comic books. |

|

Moór was born in Kecskemét, Hungary, and studied in Prague, Vienna and Budapest. Between 1885 and 1897 he toured Europe as a soloist and ventured as far afield as the United States. Besides five operas and eight symphonies his output also included: concertos for piano (4), violin (4), cello (2), viola, and harp; a triple concerto for violin, cello, and piano; chamber music; a requiem; and numerous lieder. He died, aged 68, in Chardonne, Switzerland. His best-known invention was the Emánuel Moór Pianoforte, which consisted of two keyboards lying one above each other, and allowed, by means of a tracking device, one hand to play a spread of two octaves. The double keyboard pianoforte was promoted extensively in concerts throughout Europe and the United States by Moór's second wife, the British pianist Winifred Christie. Maurice Ravel said that the Emánuel Moór Pianoforte produced the sounds he had really intended in some of his works, if only it had been possible to write them for two hands playing on a standard piano. Pablo Casals always believed in him and often played his works.Richard Meszto wrote, "The last decade of his life was spent developing, building and perfecting a remarkable instrument that while having only one set of strings, has two keyboards angled towards each other which allows for playing by one hand on both. The result is a massive increase in the potentialities of the instrument. Donald Francis Tovey was an early and ardent supporter, Moór's second wife Winifred Christie-Moór was a fervent activist on its behalf. Later the pianist György Sándor (who played his New York debut on the instrument) taught its methods, while the pianist Gunnar Johansen recorded the complete works of Bach in the 1950s and used one of these instruments for a vast swath of the compositions." |

GW: Not very often! It sometimes

is. Sometimes you can be up there and things are going really

well, and it’s under control — especially

on tour, when we’ve played a Mozart symphony eight or ten times already,

so you feel more comfortable about the technical things, and you know

that it’s going to hang together and make sense, and that the players

will come in at the right places. There’s a security in the ensemble,

and then you can begin to let-up a little. But still, for me anyway,

it takes every ounce of concentration I’ve got, and even at that, I’ve

never felt I’m really in control of things. So, I can never relax

and say I’m enjoying this. I don’t know about other conductors,

but for me it’s just a very busy process. If it isn’t one thing, it’s

the other. You wish you had ten hands a lot of the times so that you

could give all the help that needs to be given.

GW: Not very often! It sometimes

is. Sometimes you can be up there and things are going really

well, and it’s under control — especially

on tour, when we’ve played a Mozart symphony eight or ten times already,

so you feel more comfortable about the technical things, and you know

that it’s going to hang together and make sense, and that the players

will come in at the right places. There’s a security in the ensemble,

and then you can begin to let-up a little. But still, for me anyway,

it takes every ounce of concentration I’ve got, and even at that, I’ve

never felt I’m really in control of things. So, I can never relax

and say I’m enjoying this. I don’t know about other conductors,

but for me it’s just a very busy process. If it isn’t one thing, it’s

the other. You wish you had ten hands a lot of the times so that you

could give all the help that needs to be given. GW: For many years I was a consumer of music, and bought

recordings and listened to the difference between Claudio Abbado and Solti’s Mahler.

I’m glad I did that. It was a good part of my life, but I don’t

do that anymore. It doesn’t seem relevant much more to me what

Solti does, so I’m not such a consumer of music. I’ll go to hear

a good concert occasionally, but depending on the repertoire that they’re

doing I’m old-fashioned there, too. If you think back a hundred

years ago, how conductors learned symphonies, they sat down at the piano

four hands, and played with their sister, or their fellow students, or

some other conductor. So, the learning of music was a real hands-on

process that you did yourself. Since the advent of the phonograph

record, it’s become a more passive process, even though going to a concert

is also a passive process. If you go hear Furtwängler do the

Beethoven Ninth, or you listen to a recording of it, if you understand

the difference between a frozen record and a live performance you can learn

a lot. Conductors should be very aware of traditions of performance

— knowing how Weingartner conducted and Toscanini

conducted, because so much of the repertoire that we do is connected

to their time. Time’s going by, but there are conductors alive

— like Monteux, who gave the first performance

of The Rite of Spring. We can listen to his recordings and

learn a lot from them. It’s too bad we couldn’t hear a recording

from 1913 and see how it really sounded. To me, that’s important

part. There’s this whole big thing of ‘authentic’ performances on

original instruments, so when I made the Reznicek recordings, I tried to

make the orchestra sound like it might have sounded back in 1920 when that

music was first performed... not to be fanatical about it, but to consider

putting the second violins on the right, where they were in those days,

and things like that. So, authentic performance can also be right up

to 1820s and 1830s.

GW: For many years I was a consumer of music, and bought

recordings and listened to the difference between Claudio Abbado and Solti’s Mahler.

I’m glad I did that. It was a good part of my life, but I don’t

do that anymore. It doesn’t seem relevant much more to me what

Solti does, so I’m not such a consumer of music. I’ll go to hear

a good concert occasionally, but depending on the repertoire that they’re

doing I’m old-fashioned there, too. If you think back a hundred

years ago, how conductors learned symphonies, they sat down at the piano

four hands, and played with their sister, or their fellow students, or

some other conductor. So, the learning of music was a real hands-on

process that you did yourself. Since the advent of the phonograph

record, it’s become a more passive process, even though going to a concert

is also a passive process. If you go hear Furtwängler do the

Beethoven Ninth, or you listen to a recording of it, if you understand

the difference between a frozen record and a live performance you can learn

a lot. Conductors should be very aware of traditions of performance

— knowing how Weingartner conducted and Toscanini

conducted, because so much of the repertoire that we do is connected

to their time. Time’s going by, but there are conductors alive

— like Monteux, who gave the first performance

of The Rite of Spring. We can listen to his recordings and

learn a lot from them. It’s too bad we couldn’t hear a recording

from 1913 and see how it really sounded. To me, that’s important

part. There’s this whole big thing of ‘authentic’ performances on

original instruments, so when I made the Reznicek recordings, I tried to

make the orchestra sound like it might have sounded back in 1920 when that

music was first performed... not to be fanatical about it, but to consider

putting the second violins on the right, where they were in those days,

and things like that. So, authentic performance can also be right up

to 1820s and 1830s. GW: [Thinks and then laughs] First

of all, they need a real understanding that it’s a very limited thing

they want to do in terms of symphony orchestras, because symphony orchestras

are fighting their own battles for survival. The trend is more

towards a commercial view of all this, and more pops concerts.

The bills have to be paid, and we know symphony orchestras are not anything

but cultural institutions that need public support, and in this country,

mostly private and corporate support. But the crunch is on,

and orchestras now have to have ways to earn money, so they turn more

and more to pops concerts, and things like that to help pay the bills.

For composers, it is very difficult to get their idealistic pieces played,

because the orchestras have to have public support. They have

to understand there has to be a balance, so that the new music will

get played, and the old music will get played, and Brahms symphonies

will continue to get played, and that contemporary music will fit into

that somehow. But new music is not going to dominate. It’s

going to be always something that’s a fraction of the whole picture for

symphony orchestras in order for them to survive. It’s not the most

idealistic view, but it’s how things are today.

GW: [Thinks and then laughs] First

of all, they need a real understanding that it’s a very limited thing

they want to do in terms of symphony orchestras, because symphony orchestras

are fighting their own battles for survival. The trend is more

towards a commercial view of all this, and more pops concerts.

The bills have to be paid, and we know symphony orchestras are not anything

but cultural institutions that need public support, and in this country,

mostly private and corporate support. But the crunch is on,

and orchestras now have to have ways to earn money, so they turn more

and more to pops concerts, and things like that to help pay the bills.

For composers, it is very difficult to get their idealistic pieces played,

because the orchestras have to have public support. They have

to understand there has to be a balance, so that the new music will

get played, and the old music will get played, and Brahms symphonies

will continue to get played, and that contemporary music will fit into

that somehow. But new music is not going to dominate. It’s

going to be always something that’s a fraction of the whole picture for

symphony orchestras in order for them to survive. It’s not the most

idealistic view, but it’s how things are today.

BD: Do you have a concert every week?

BD: Do you have a concert every week?  BD: Is there no way of stopping it?

BD: Is there no way of stopping it? GW: There are people who do that, although

they buy their sugar and salt, and bacon and beans, and they have

their sprouts sent in. But I would say that there are not many

purists who do it just from the land. Even the natives who live

a subsistence lifestyle, do have some cash economy... and more and

more soda pop. You look at airplanes going into the bush villages,

and they’re all filled with soda pop. Everybody gets diseases,

and their teeth rot. The two worst things that I’ve seen come

to Alaska are the missionaries and soda pop... not to mention alcohol,

and venereal diseases, and things like that. But it’s sickening

to go to these villages and see these little kids eating a candy bar,

and sucking on a soda pop all the time. It’s just sad. It

really is sad.

GW: There are people who do that, although

they buy their sugar and salt, and bacon and beans, and they have

their sprouts sent in. But I would say that there are not many

purists who do it just from the land. Even the natives who live

a subsistence lifestyle, do have some cash economy... and more and

more soda pop. You look at airplanes going into the bush villages,

and they’re all filled with soda pop. Everybody gets diseases,

and their teeth rot. The two worst things that I’ve seen come

to Alaska are the missionaries and soda pop... not to mention alcohol,

and venereal diseases, and things like that. But it’s sickening

to go to these villages and see these little kids eating a candy bar,

and sucking on a soda pop all the time. It’s just sad. It

really is sad. GW: No, no, no, it’s this guy in California

that invented all the instruments, Harry Partch, and those people.

He just went right from Rock’n’Roll into that, whereas some of us

went through Bach and Wagner. My training was Bach and Wagner.

That was shoved down my throat, and I loved it. I can pig-out

on those two any time, particularly Bach. So John never went

through all that. He was a percussionist, and he’s an avant-gardist,

and now he’s becoming traditional because in Alaska he’s just found

his own niche there.

GW: No, no, no, it’s this guy in California

that invented all the instruments, Harry Partch, and those people.

He just went right from Rock’n’Roll into that, whereas some of us

went through Bach and Wagner. My training was Bach and Wagner.

That was shoved down my throat, and I loved it. I can pig-out

on those two any time, particularly Bach. So John never went

through all that. He was a percussionist, and he’s an avant-gardist,

and now he’s becoming traditional because in Alaska he’s just found

his own niche there.

========

========

========

-- -- -- -- -- -- --

======== ========

========

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 2, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1990, 1995 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.