Philip Hagemann (born December 21, 1932) is an American composer and conductor.

Hagemann was born in Mount Vernon, Indiana, the son of Harry Philip and

Lorene (Knight) Hagemann. He learned to play the piano and the saxophone,

and took music degrees at Northwestern University in Evanston and Columbia

University. From 1954-1956 he served in the US Army. He was a choral conductor

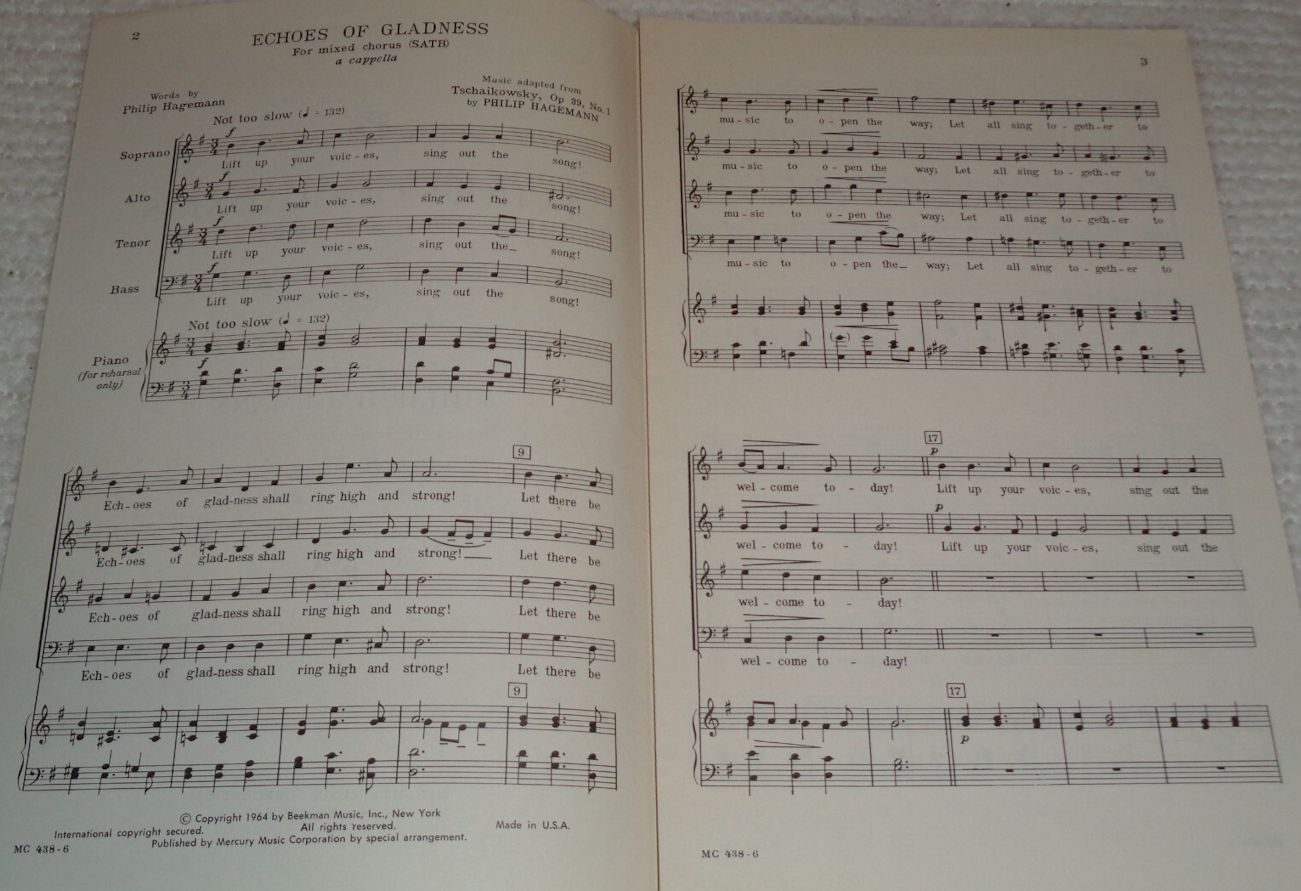

in New York, and has published 75 works for choir.

Hagemann was born in Mount Vernon, Indiana, the son of Harry Philip and

Lorene (Knight) Hagemann. He learned to play the piano and the saxophone,

and took music degrees at Northwestern University in Evanston and Columbia

University. From 1954-1956 he served in the US Army. He was a choral conductor

in New York, and has published 75 works for choir.

He has composed 10 one-act operas and two full-length operas. His first opera was The King Who Saved Himself from Being Saved (1976), a work for children based on a story by John Ciardi. Five of his operas are based on works by George Bernard Shaw; these include The Music Cure (1984), and Shaw Sings! (1988), which includes The Dark Lady of the Sonnets and Passion, Poison and Petrifaction. Other operas include works based on Henry James's The Aspern Papers, (which premiered at Northwestern University on the same night, November 19, 1988, that Dominic Argento's opera on the same story premiered in Dallas), Edith Wharton's Roman Fever (1989), and Oscar Wilde's The Nightingale and the Rose (2003).

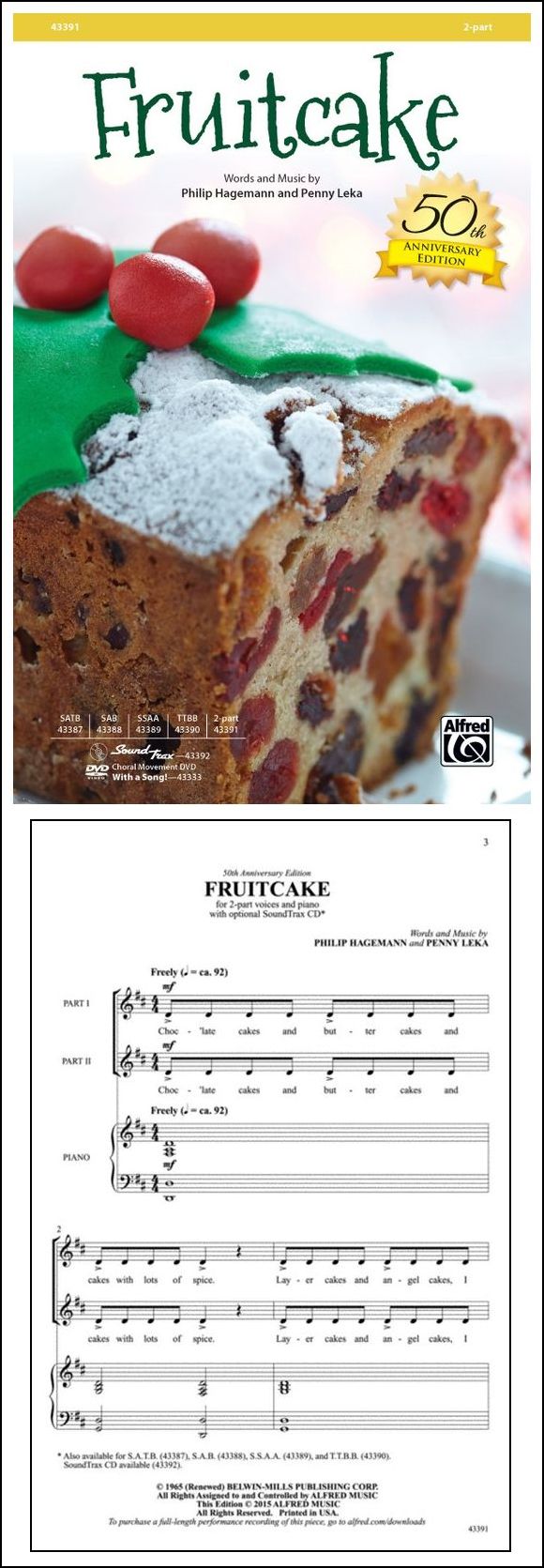

Among his other compositions are two choral cycles based on the verses of Ogden Nash, A Musical Menu and A Musical Menagerie. His Christmas choral piece Fruitcake [shown below-left] which includes both spoken and sung passages, is a humorous version of the cake recipe, and has sold over 150,000 copies of sheet music.

The music critic Anthony Tommasini has written of Hagemann, "His music may lack a strong contemporary profile: his language is essentially tonal and lushly chromatic. Whole-tone melodic patterns recall Ravel". He added that "he injects grittiness into his music through the piling up of clusters and dissonance. He also writes effectively for the voice"