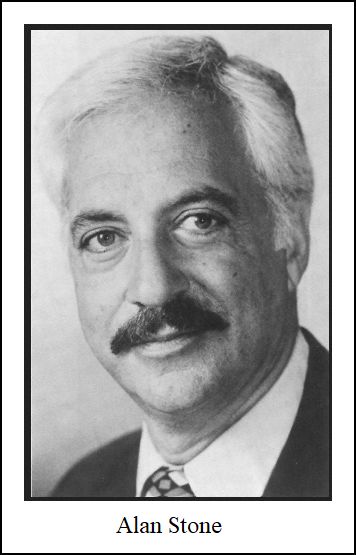

Alan Stone

Founder

and Artistic Director

of the

Chicago Opera

Theater

Four Conversations

with Bruce Duffie

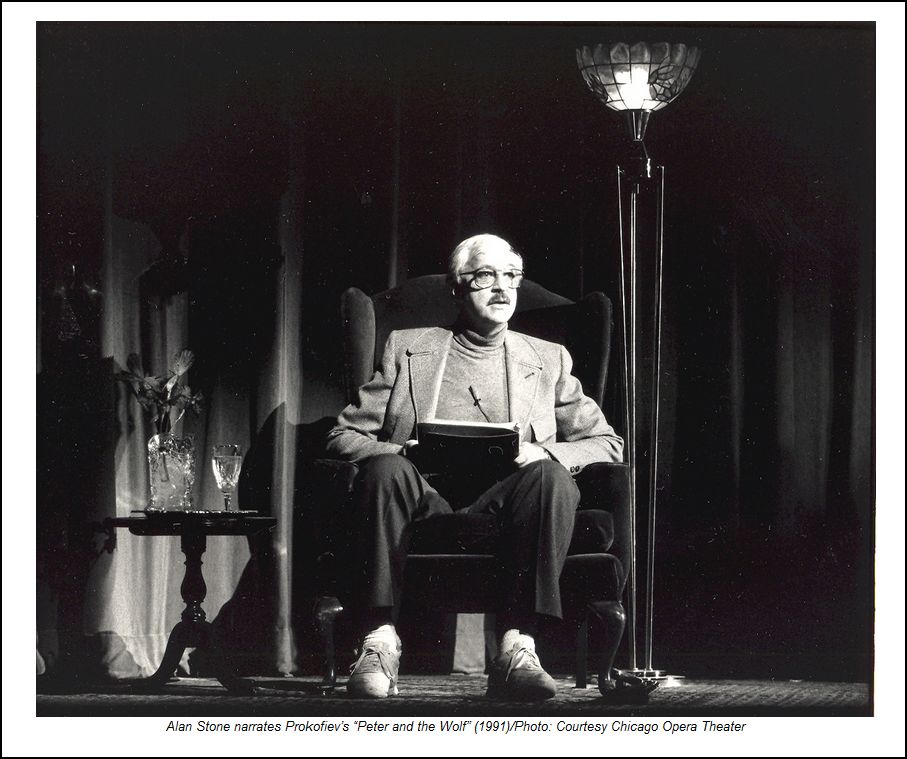

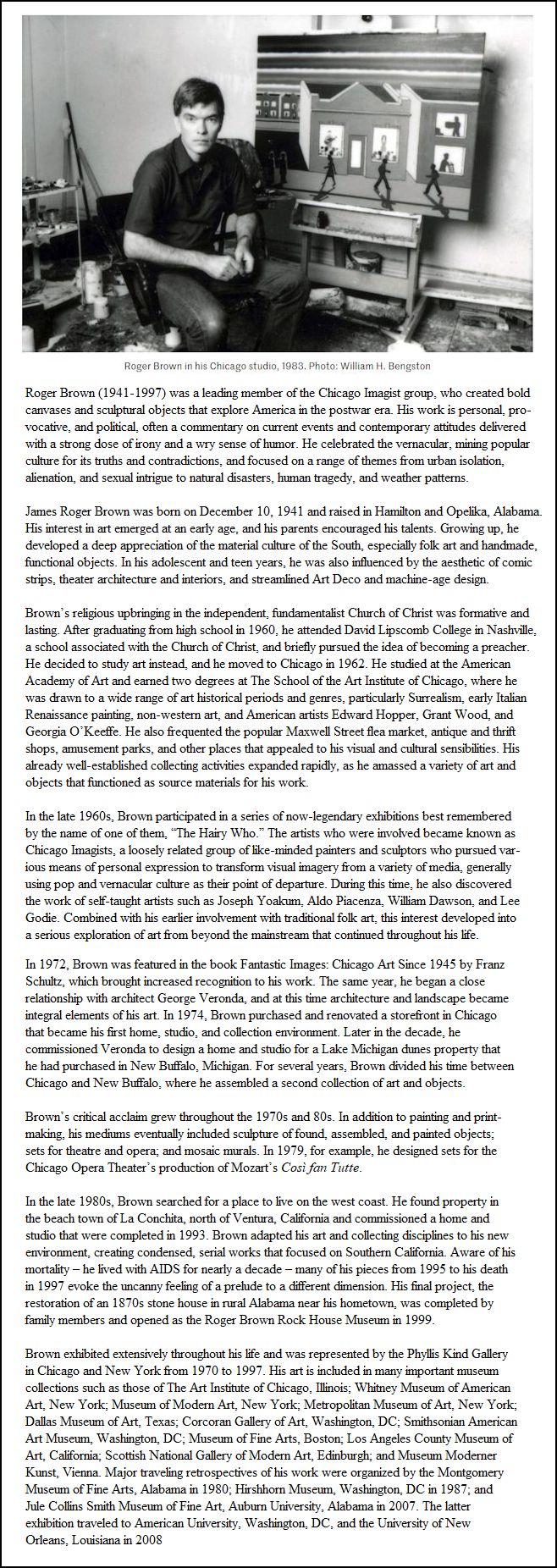

Alan Stone (April 28, 1929 – July

9, 2008) was an American opera director, opera singer,

and vocal coach.

Born and

raised in Chicago, Stone founded the Chicago Opera

Studio, Inc., which later became the Chicago Opera

Theater. He served as Artistic Director until

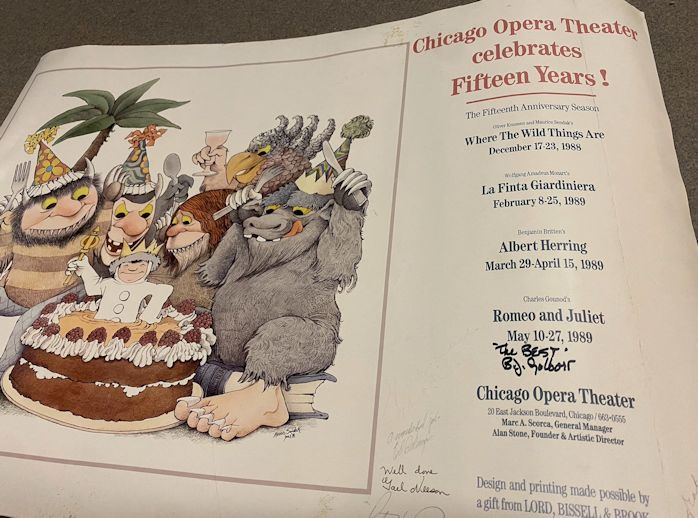

1984, and remained with the company as an advisor until

1993.

Some of the Chicago premieres presented under

Stone's tenure include Virgil Thomson's

The Mother of Us All (1976 & 1984), Marc Blitzstein's

Regina (1982), Carlisle Floyd's

Susannah (1986) and Of Mice and Men (1988 - directed

by Arthur Masella),

Robert

Ward's The Crucible (1985), and Dominick Argento's

Postcard from Morocco (1991).

|

With the exception of my second conversation with

George Jellinek,

all of the interviews I did for WNIB from 1975 to 2001

were pre-taped. I would then edit

a portion for use on the air. That way my guests

and I could relax and not have to watch the clock. This

method also afforded me the opportunity to speak with these

musicians about many areas of mutual interest. When

transcribing them for my website, the entire encounters

have been presented, and I am happy to report that the response

from readers has been completely positive.

Most of the meetings were singular

events. Occasionally I would be able to speak

with a guest twice, but the material on this webpage

presents four times I interviewed the Founder of the Chicago

Opera Theater, Alan Stone. While the first purpose

was to promote specific upcoming performances, Stone

also gave much insight into the workings and problem-solving

needed to sustain a small and growing opera company.

In each case there was much laughter,

as well as serious discussion. For this website

presentation, I have eliminated most of the detailed

listings of exact locations, dates, times, and ticket

prices. The radio audience needed that information,

but it is unnecessary here. All names which are links

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. Brief

biographies of some of the other artists he mentions are scattered

throughout the webpage, and are indicated by an asterisk (*).

We begin in February of 1979

. . . . .

Bruce Duffie: As you head

into your fifth anniversary season, are you pleased

with where the company is going?

Alan Stone: We’ve

come a long way. If you remember, when we

started the organization in 1974 with our first production

of Così Fan Tutte, we were called

The Chicago Opera Studio. We changed our name over

a year and a half ago, and that also reflects a change in

the company toward a more professional look and feel, and

away from the school image that the word ‘studio’ represented.

Certainly, when we did our first production, we were

a studio. Nobody was paid, including myself.

The singers were not paid, the directors were not paid,

and the orchestra was a very minimal student orchestra.

BD: Now you have

a permanent home, or a semi-permanent home at

the Athenaeum Theater?

Alan Stone: This will be

our second season at the Athenaeum. [Photo of the

Athenaeum is shown below.]

BD: Is it working out

the way you want it?

Alan Stone: Yes. We

have found a very congenial home in many ways.

Being about 930 seats is just right for our size

operation, and my own concept of the way opera should be

seen, in a relatively small theater. It is very much

like the European theaters, most of which are about 1,000

or 1,500 seats.

It looks like an old-world

theater. It has a little bit of that feel and

charm. People think opera ought to be in that kind of

a place.

BD: In these five years

you’ve made a lot of progress with your group?

Alan Stone: We’ve made

extraordinary progress. People these days

measure things with dollars and cents, and in those

terms our first annual budget was $8,000 for the entire

year. This year our annual budget will be reach

about $240,000. We’re also up to doing three productions

a year, whereas for the first two seasons we only performed

one opera a year. Then for three seasons we did

two operas. This is our fifth birthday, and we’re up

to three productions. We’re doing six performances

of the first work, four of the second, and six of the third,

so we’ve got sixteen performances of three different works.

We’ve got 16,000 tickets to sell.

BD: What are the three

operas that you are doing this year?

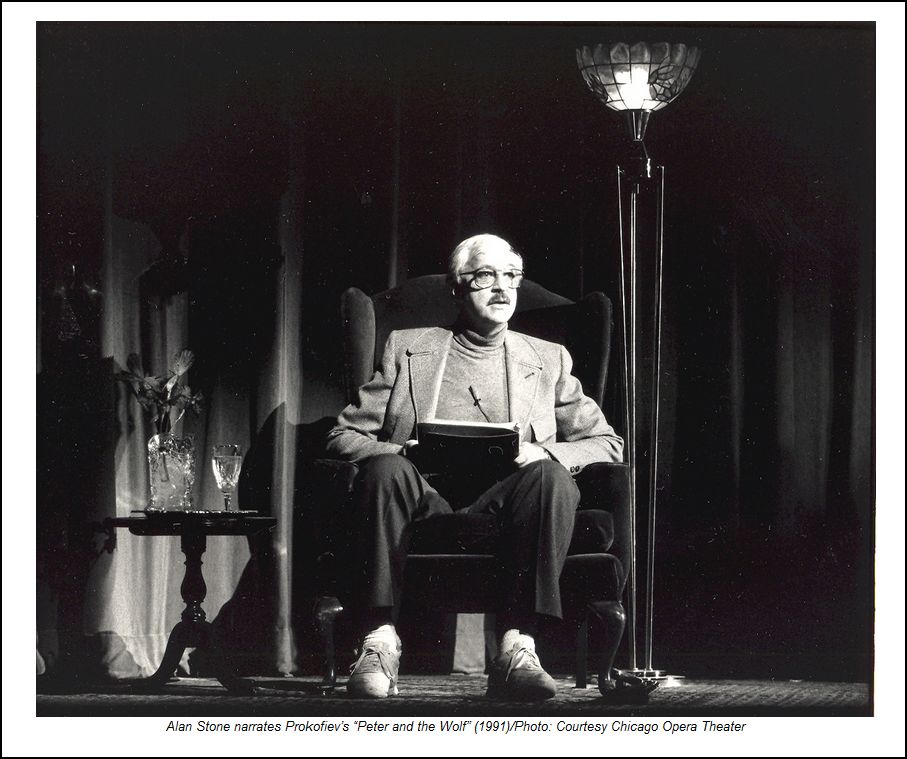

Alan Stone: We’re doing

Così Fan Tutte again, but I want

to stress to all of your listeners that this is not the

same production. The first production was done with

spit and gum, and cardboard cracker-jack sets, and rented

costumes, and borrowed props. It was a real

thrown-together production. We had no money.

In fact, you shouldn’t call it the old production!

It was a no-production because we have nothing left of

it. It was all fed to the fire when the show closed.

Now we have a really beautiful and exciting production.

We received a grant from the National Endowment for

the Arts in the visual arts program, to have a local artist

design the sets and costumes. We commissioned the Chicago

artist, Roger Brown*, who is very well known in this area,

to do this production. He has paintings hanging in the

Art Institute, and the Contemporary Arts Museum. Along with

this all-new production, Corinna Taylor has been working with

Roger doing the costumes. We also have a mostly new cast.

Two of the cast members appeared in the first production, but

they are appearing in different roles in this production.

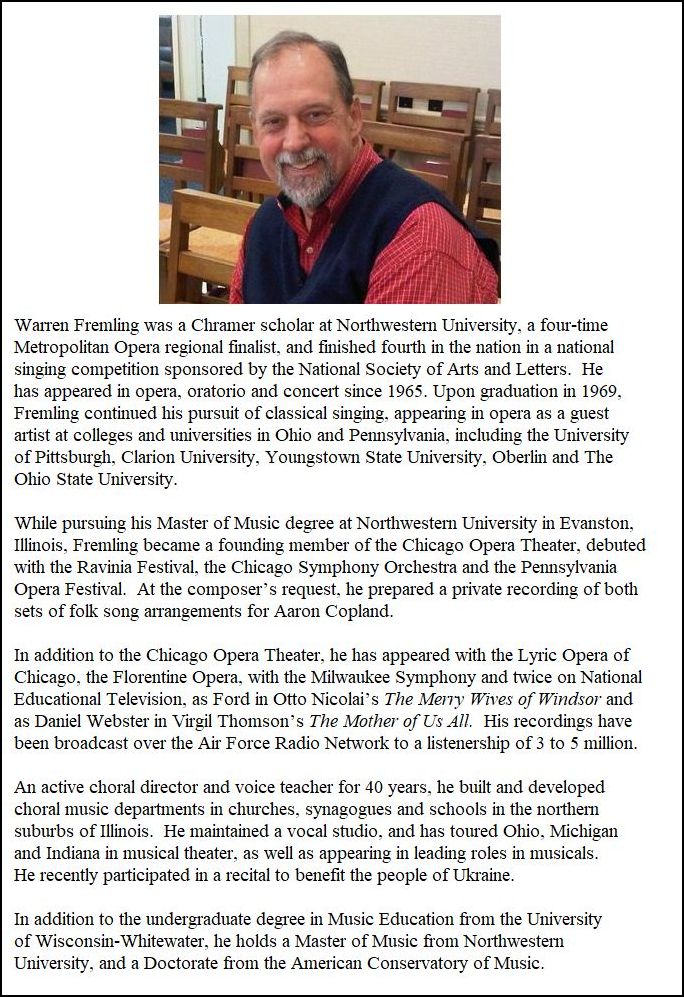

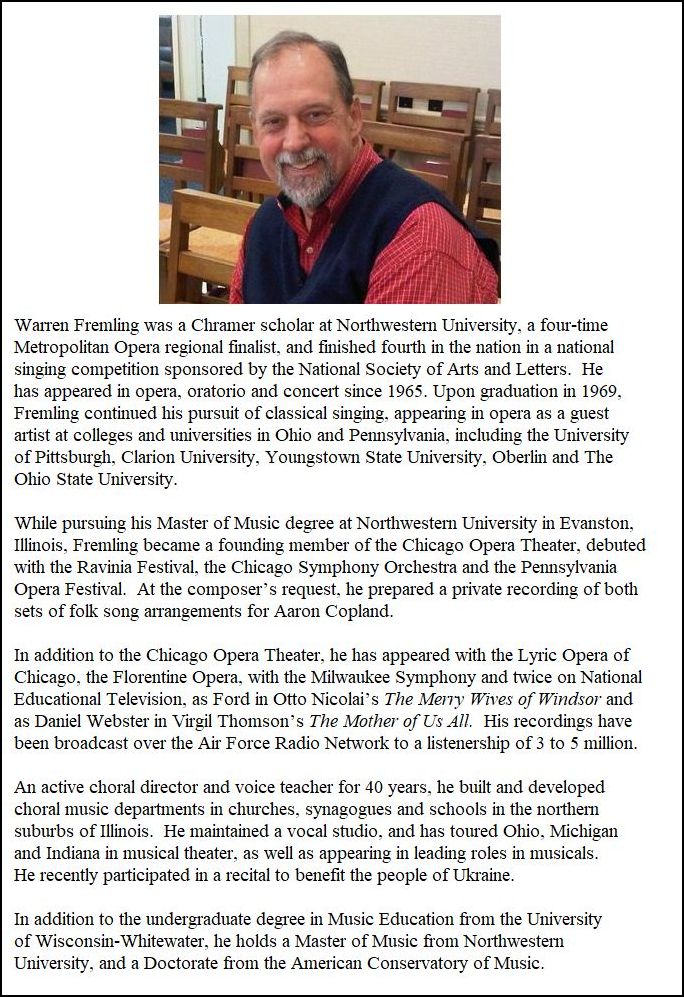

Warren Fremling*, who sang Mr. Ford most recently in our The

Merry Wives of Windsor, and is probably best remembered as

Figaro in The Marriage of Figaro, sang the part of Don

Alfonso in the first production of Così in 1974,

but in this production, I have cast him in the role of Guglielmo.

BD: Isn’t that a higher

part?

Alan Stone: Strangely enough,

it isn’t higher. People think it’s higher,

but it’s actually lower, and in the ensembles,

the Guglielmo part is written under the Don Alfonso. But

they’re very, very close.

BD: Isn’t Guglielmo the

more lyric part?

Alan Stone: It’s a more

lyric part. It’s a role for a younger man,

whereas Alfonso is the older bachelor. But I thought

we had given Warren enough of those heavy villainous

roles, and for once we ought to capitalize on his charm,

and his wonderful warm personality.

BD: Let him play a lover

this time?

Alan Stone: Let him be

a lover like he did in Figaro. He’s

lovable as Guglielmo. The other hold-over, and

turn-around, is our wonderfully popular Robert Orth. He did

Guglielmo before, and now I have cast him as

Don Alfonso. Bob is a wonderful actor, and

I felt that Alfonso offers much more opportunity for

subtlety of acting. I’m from the old-time school

when Alfonso was sung by a baritone. The first time

I heard Così Fan Tutte was with one of the

greatest Mozart baritones, John Brownlee. He was the classic

Don Alfonso, and Count, and Don Giovanni, and many other

roles as well.

BD: Being an armchair impresario,

I would have given Orth the part of Guglielmo,

as you did earlier.

Alan Stone: Yes, but his

suavity and his elegance sold him in the role of

Alfonso. So, they are the only two that appeared

in the original production, and it will be interesting

to see them in these new roles. They’re also

very excited about the challenge of doing the other parts.

BD: We’ve talked about two

of the three men. Who is the tenor?

Alan Stone: The tenor is

a wonderful man who has appeared with us in two

previous productions. His name is William Eichorn.

You will remember him from The Mother of Us

All in 1976. He did the part of John Adams,

and the next year he sang a much more prominent

role, Belmonte in The Abduction from the Seraglio.

He is a fine tenor, a wonderful Mozart singer,

and we’re very proud of the fact that just recently

he won the Plácido Domingo Award for Singers in Barcelona,

Spain. He had all kinds of notoriety, and we’re

really proud to have him.

BD: Who will be singing

the three female parts?

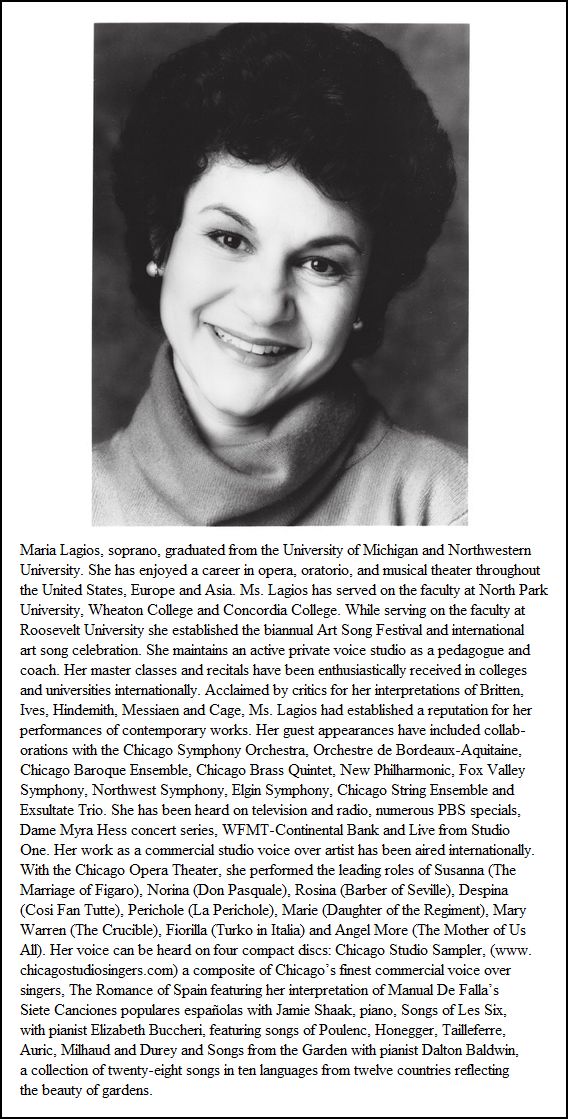

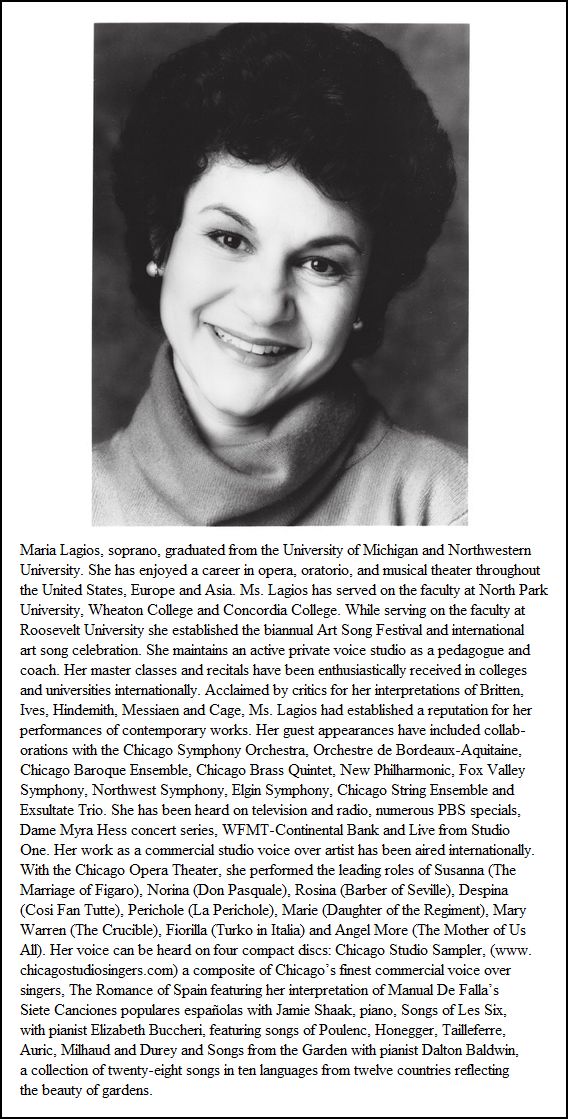

Alan Stone: In the role

of Despina, the little maid to the two elegant

Ferrarese sisters, we have our really lovely and

beloved Maria Lagios*. She has appeared with

us as Norina in Don Pasquale, Rosina in The

Barber of Seville, Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro,

and she was also in The Mother of Us All.

Maria is really a staple with the company, and whenever

I see these kinds of roles, I already have her in mind.

She’s absolutely adorable in all these parts, and Despina

is a role that was made for her. In the role of the

younger of the two sisters, Dorabella, we have a very lovely

lady from Chicago, a mezzo-soprano from the Calumet City

area, whom I have known, and who has auditioned for us for many,

many years, but we never have seemed to find the right part for

her. But this year she scored. Her name is Joyce Carter.

Then, in the role of Fiordiligi, the older, sedate, more elegant

and strong-minded sister, we have a young lady who is a student

at Northwestern University. I was very much impressed

when she auditioned for us, and Karen Huffstodt* is her name.

In addition, I have a group of alternate singers who will be

not only covering these other people in case of an emergency

or illness, but they will be doing one matinee student performance

that we’re doing for the Urban Gateways Group, sponsored by

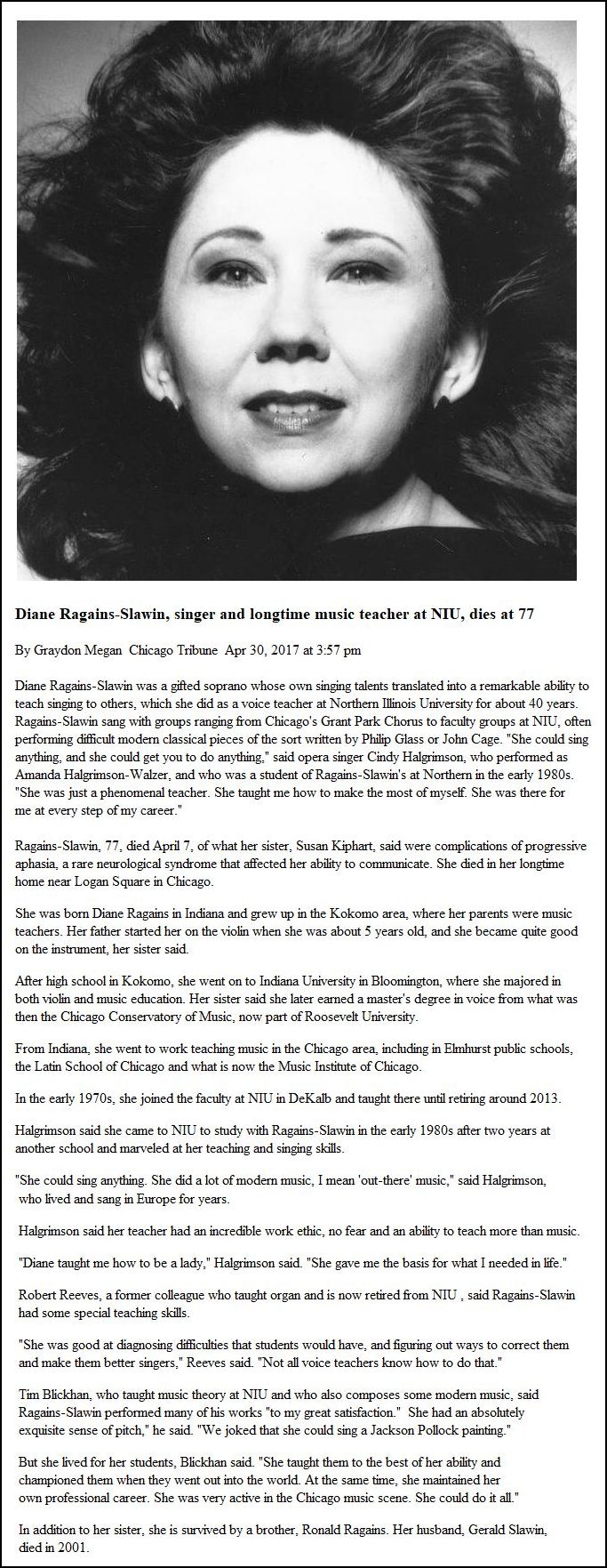

the Field Foundation on February 28th. That group includes

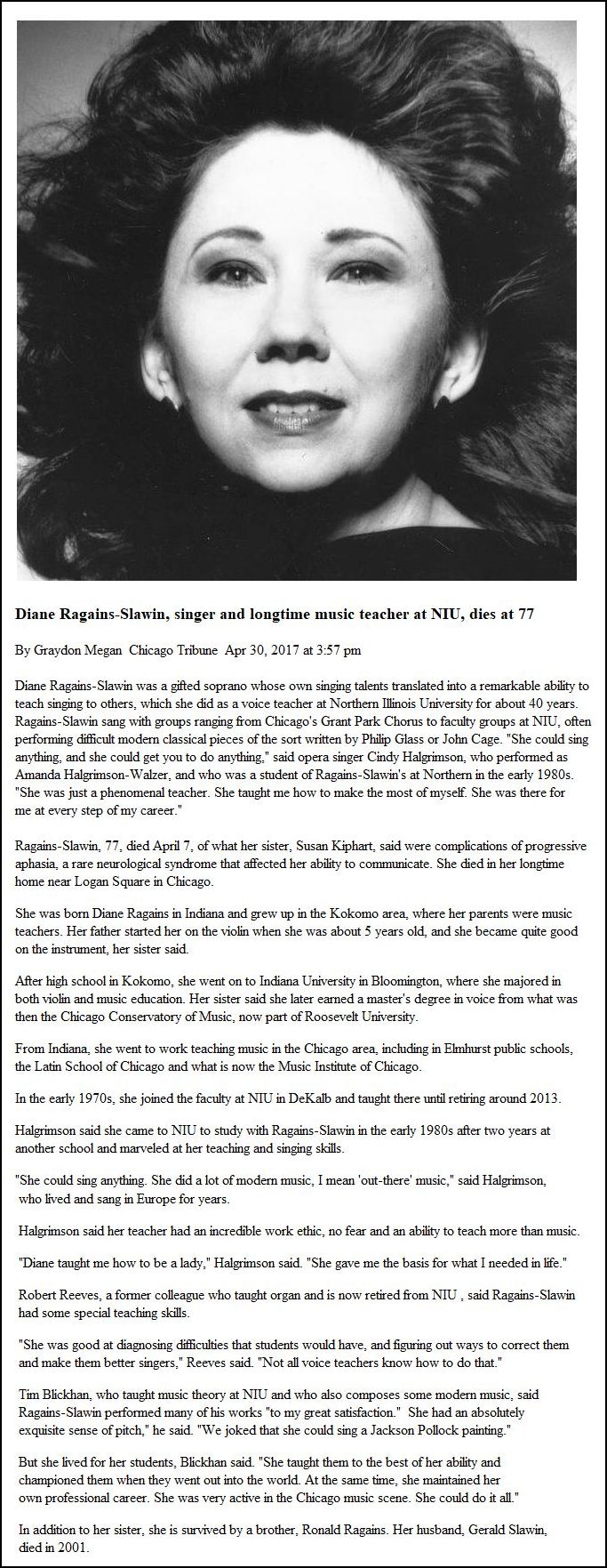

Diane Ragains*, who sang this last season at Grant Park, and

has appeared with the Symphony, who will be doing Fiordiligi;

Kathleen Ferrin, who sings with the Chicago Symphony Chorus,

and has done lots of work in Chicago, will be Dorabella; Arlene

Barkley-Bright, who has appeared with us in the past as Blonde

in Seraglio is our Despina; Henry Hunt, who was our Ernesto

in Don Pasquale will be singing Ferrando, and Lee Snook will

be our alternate Guglielmo. Snook also has appeared with

us in touring performances Don Pasquale. Our

alternate Don Alfonso will be Warren Fremling, who is doing

our Guglielmo. He already knew the role, and it was an

expeditious thing to do. So, we’re covered now in case

of accident and, with this winter so far, we never know what’s

going to happen, be it illness, or a car that doesn’t start,

or snow...

BD: [Feigning alarm] Don’t

say snow! We have already had more than

enough this winter! [Both laugh]

Alan Stone: I shouldn’t

mention snow! I’m never going to do

The Snow Maiden of Rimsky-Korsakov. We’ll

skip that one, and do only summer-scene operas!

BD: We’ll rename you The

Fair-Weather Opera Company!

Alan Stone: Right, and

we won’t do all of La Bohème because

of the snowflakes in act three. We’ll just have

to cut that act right out of the opera!

BD: Keeping that in mind,

what are the other operas that you are doing this

season?

Alan Stone: We’re doing

a most interesting season of which I’m really

proud. It’s going to be hard for me to find a

similar balance in future seasons. Our first work

is Mozart, so that’s the late eighteenth century.

Then our second work is a brilliant opera that has never

been done in Chicago, so we’re adding still another Chicago

premiere to our list. We’ve done several Chicago

premieres, as you know. In the past, The Merry

Wives of Windsor was a Chicago premiere in a professional

production, as was The Mother of Us All, and Summer

and Smoke [by Lee Hoiby].

Our production of The Abduction from the Seraglio was

the first one that had been done around here in something

like thirty years. So, we have always been very adventurous

and very innovative in repertory. That’s something

we’re dedicated to.

BD: So, what is this new

work for this season?

Alan Stone: I don’t want

to scare our audience, because it’s nothing really

that avant-garde. It isn’t all that new, but

it’s new for Chicago. It is the marvelous comedy

of Benjamin Britten Albert Herring. There

was a recent production of it on the television from the

St. Louis Opera, and I attended that production just to decide

whether or not I really wanted to do the work. I had never

seen it, and when I saw it and heard it, I really fell in love

with it. It is a wonderful work, one that is right

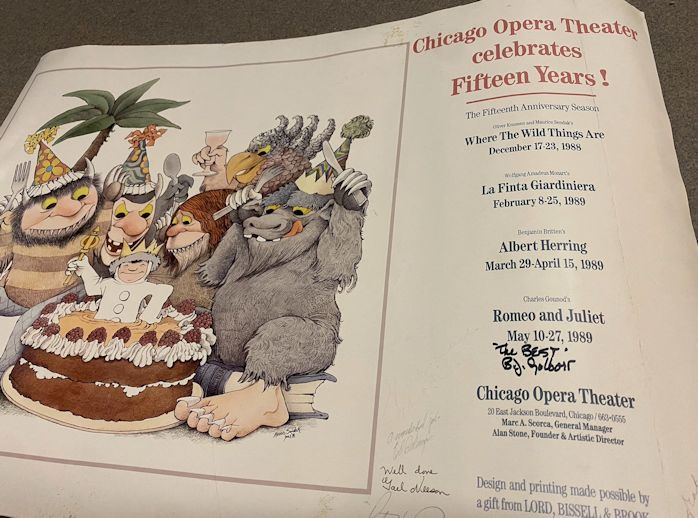

up our ally. It’s brilliant. [In addition to this

1979 production, COT would revive the work ten years later (in 1989)

conducted by Hal

France, and again in 2022-23.]

BD: It has a lot of intimate

dramatic possibilities?

Alan Stone: It has wonderful,

intimate dramatic situations, and is also a real

ensemble opera. There are thirteen characters,

and of those thirteen, I would say that at least ten

are very large leading roles.

BD: So there are lots of

opportunities for the young singers.

Alan Stone: Lots of opportunities,

and it comes across as a whole company effort,

rather than an opera which is a vehicle that you can

build around one singer. It is going to be directed

by Frank Galati,

who directed our production of The Merry

Wives of Windsor. He also did The

Mother of Us All, and Summer and Smoke.

He is a very theater-orientated person. The story

of Albert Herring is so brilliant and so amusing,

I know he’s going to make something just wonderful

out of it. I should also like to mention that the director

of our Così Fan Tutte is Peter Amster,

who was our choreographer for The Merry Wives of Windsor,

and co-director of The Mother of Us All.

Peter has a great background in musical comedy, and also has worked

a great deal as a dancer. You’ll see the dancer’s

touch in Così Fan Tutte which the music can use.

BD: It needs elegance.

Alan Stone: Yes, it does

need a lot of that lightness and buoyancy.

BD: As long as we’re giving

credits here, who is the conductor for all

of these operas?

Alan Stone: Our conductor from

the very beginning is a man who helped me so much

initially in the forming of the company, Robert Frisbie

[who also participates in my interview with Lee Hoiby].

He will conduct all the productions, and he’s

now also conducting his own American Chamber Symphony. He’s

really beginning a very busy career, and that is not an

easy thing to do. It’s hard being a singer, but it may

be harder being a conductor. A singer can walk around with

his pipes, but a conductor can’t carry his orchestra around in

his briefcase.

BD: Much as he’d like

to!

Alan Stone: [Laughs]

Much as he’d like to, right.

BD: What is the third work

for this new season?

Alan Stone: The third

is a work that seems to be a great favorite of

audiences. I understand that there are more requests

for this opera than any other opera, and that is

Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers.

BD: Oh, with the wonderful

duet.

Alan Stone: Yes, it

has the wonderful duet that everyone remembers between

the tenor and the baritone. But there is also

some wonderful music between the tenor and the soprano,

and wonderful music for the tenor by himself, as well

as wonderful music for the soprano, and some marvelous music

for the baritone, and brilliant choral music. It’s

a very, very big choral opera, and we will have the largest chorus

that we’ve ever had, as well as squeezing in the largest

orchestra that we’ve ever had into the pit at the Athenaeum.

The largest drawback we have at the Athenaeum is the size

of the orchestra pit [shown in photo at right].

We can only get about thirty players in there. Most

of the nineteenth century operas call for more, so we have to

eliminate them because they are impossible

to do with just thirty players. You need a bigger

orchestra for them.

BD: I won’t wait for a

Wagner performance with your company.

Alan Stone: No, don’t wait

for us to do Wagner, and I’m afraid you’re

going have to wait for a long time for Puccini,

or for any of the romantics of the nineteenth century.

BD: But these are done

elsewhere, and on recordings, and in productions

on television. It’s a great joy to have your

company doing operas that we don’t see all the time.

Alan Stone: I’m very happy

to hear you say that, because you’ve really summed

it up nicely. That’s exactly my philosophy.

People ask me why I don’t like Traviata. I

love Traviata, and that’s why I don’t want

to do it. I would not want to subject an audience

to the musical and artistic compromises that we would

have to do to put it on, or to do Il Trovatore,

or Turandot, or so many other favorites.

BD: You do things in a different

way because it’s a much more intimate setting.

Alan Stone: Plus the fact

that we do things in English. We are always

stressing the theatrical aspects, and this year

we have got a balance. We’re doing an eighteenth century

work, a nineteenth century work, and a twentieth century

work.

BD: Interesting repertoire

that is not always done.

Alan Stone: Yes.

BD: But they are all charming

works. These are not new works you’re experimenting

with. These are all works that have proved

themselves.

Alan Stone: Exactly!

They’re not unknown works that we don’t know what

to expect. There is some precedence.

We know that Albert Herring has brought the

curtain down to a tumultuous applause many, many

times. The Pearl Fishers has been recorded,

and Così Fan Tutte has been a staple

since 1790 when it was written. I like the combination

of an early work, be it a Mozart or Rossini or Donizetti,

coupled with a contemporary work. Strangely

enough, the demands on the orchestra are very similar between

the eighteenth or early nineteenth century works, and then

the twentieth century works. It was in the mid-nineteenth

century that the orchestras grew. Perhaps a modern

composer, because of his knowledge of wanting to get his work

performed, realized it was practical to build an opera that could

feasibly be produced by a smaller company.

BD: Do you think there

will come a time when the Chicago Opera Theater

will be commissioning a world premiere?

Alan Stone: That possibility

is quite strong. There are many composers

who are anxious to have works commissioned, and they

generally can be mounted by smaller companies.

A company like Lyric Opera, the Metropolitan, and San Francisco

will not take a chance, except for the work of a fairly

monumental nature, such as Paradise Lost [by Penderecki].

But the time will come, provided

that we can get support and proper funding,

that we will commission a work. As our audience

grows, we will become more and more courageous,

and be able to take a chance on a work, because we know

that people will buy a subscription, and will be more

adventurous.

BD: People will know

that you’re going to give it the same treatment

that you give the other operas they enjoy?

Alan Stone: Yes, and they

will trust us, and know that we will give them

something that is worthy, even though they may not know

what it is, or what it will be.

* * *

* *

BD: As you head into your

fifth anniversary season, did you think that you

would be at this point five years ago?

Alan Stone: No, I never

did. I started this company primarily

as a showcase, as an experimental workshop. It

was a hobby for me, and it was a place for singers to

get a chance to sing and learn something. When

we did Così Fan Tutte the first time,

I don’t even think I was considering looking any further

than that first season. It was an outlet. It was

a culmination of a study process. It was a practical

thing you do when you have an opera workshop in school.

You put on a performance because you’ve worked all

year, and you have to show to the public that you’ve done

something with your time.

BD: Is this the first

time you’ve repeated a work?

Alan Stone: This is the

first time we’ve repeated a work, and as we know

from many opera companies, there’s a great percentage

of the same operas which are done year after year after year.

Only a few new productions come in. As time

goes on, there are a few staples in our warehouse that

we should bring out again, like The Mother of Us All

[1976 & 1984], Summer and Smoke [1977 & 1980],

and The Merry Wives of Windsor [1978 & 1990]. These

are things that really have our own very personal stamp, and

if we don’t do them, people won’t hear them.

BD: Are there any plans now

for anymore television?

Alan Stone: For the time-being,

we’re in a holding pattern with television.

We recently did The Merry Wives of Windsor

on WTTW, Channel 11. It was highly successful,

as was our previous production of a condensed version of

The Mother of Us All. We have received

money from the National Opera Institute to do a production

of Così Fan Tutte on television, but

for the present time we’re holding off on accepting

the grant, because we’ve learned that there are two European

productions of Così that will be released

on television within the year. We don’t want

to be compared with Salzburg or Glyndebourne, because we

have our own style, and do our thing our way. We’re

a regional company, and we’re not looking to be competitive with

the larger companies.

BD: By giving the public

a different opera, these television tapes

perhaps might even go to Salzburg and other places.

Everyone benefits by having more repertoire.

Alan Stone: It’s very possible.

We hope so anyway. We are on very good

terms with WTTW. We’ve worked with them now

on two occasions, and when the right moment arrives,

we’ll be back there in front of those cameras filming something

fine. [Taking a moment to reminisce] I remember

when I was a very young person, the first time I saw an opera

production on television was the Don Carlo that Rudolf

Bing did when he first came to the Met in 1950. The

cast had Robert Merrill,

Jussi Björling, Cesare Siepi, Fedora Barbieri,

and Delia Regal. It was black & white

on a teeny-weeny screen, and that was such an

exciting event.

BD: And that was the only

thing you had all year.

Alan Stone: It was the

only thing all year, and now there’s often something

exciting operatically on PBS, or somewhere on the tube.

[Remember, this interview was held in 1979, when

opera on the TV (and now the computer!) was much rarer than

it is in 2023.] I think the television has

done enormous things for opera.

BD: A speculative question...

Now, with the advent of opera on TV, do

you think that is going to bring more people to the

opera house?

Alan Stone: That is an interesting

question. I don’t know. If it

were me personally, it would intrigue me to go, but

I know that lots of people have found the media a substitute

for the live form, as in sports. My brother is a

big sports fan. He loves baseball, but he never goes

to a game anymore. He’s watches it on TV. I don’t

know how that would work for opera. I would hate to think

that the people who have never seen an opera would base their

judgment of it, even if it’s a good judgment, completely

on the tube, because I don’t think you can appreciate

opera on the tube unless you’ve seen it first.

BD: [Gently protesting]

But the audio recordings have been a great

boon to the live opera.

Alan Stone: Oh, yes!

BD: With the bigger repertoire,

the public can know the works and understand them.

Alan Stone: The record

industry has done a great deal.

BD: This is what I was getting

at. Will opera-on-TV feed that, or will

it send people off in a different direction?

Alan Stone: Hopefully it

will help, but I’ve heard the opinion of people

I’ve talked to at WTTW and also WNET, Channel 13 in

New York, that most of this opera stuff on television is going

to come to a crashing halt very quickly! [Let us all

breathe a huge sigh of relief that this prognostication was completely

off the mark!]

BD: Why?

Alan Stone: Because they

can’t afford it anymore. It will have to go

onto some sort of Cable TV, and people will have to pay

for it. They can’t give it away so much anymore because

it’s just become too expensive.

* * *

* *

BD: Now that your company

is five years old, how does it fit into the picture

of opera in America?

Alan Stone: We seem

to be fitting into a very comfortable and very

warm and happy niche. We recently became members

of the large organization called Opera America, which

is a conglomerate of most of the professional opera

companies in United States. We are not such a

little opera company after all. We are definitely

a middle opera company. There are many who have budgets

of $40,000 or $50,000 a year, and we have a budget of almost

of a quarter of a million dollars a year.

BD: Are you getting national

recognition?

Alan Stone: We are getting

recognition. We have been reviewed

in Opera News, the Christian Science Monitor,

Opera magazine of London, and Opéra

magazine of Paris. Opera is the largest and fastest

growing classical music art form in the United States.

There are over a thousand opera companies in the

United States of some form, and something like 600 companies

that you could call professional, in the sense that they

have professional artists, and people pay money for their

seats.

BD: The Chicago Opera

Theater is one of this group of 600?

Alan Stone: We are one

of those, yes. We haven’t been ranked yet

because we just joined the organization, but we are definitely

there, and people know what we’re doing. We’re

on their lists. We exchange artists, and designers,

and ideas for sharing productions, and so forth.

BD: What about touring?

All of these sixteen performances of the

three operas that we talked about are taking place

at the Athenaeum Theater. Will you also be doing

performances at high schools and elsewhere around town?

Alan Stone: Yes, and this

creates a terrific problem and dilemma for

us that we really must wrestle with. We recently

did a production of Don Pasquale at the Beverly

Arts Center, and next month we’ll be doing two performances

of The Barber of Seville with the Lake Forest

Symphony, plus a performance of Don Pasquale

for the Skokie Fine Arts Commission at Niles Township High School.

In addition, we have all kinds of concerts that we give

for various organizations, including Triton College, the Northwest

Indiana Symphony Opera Ball, and the Nathan Goldblatt Cancer

Society. We’re constantly being called on.

BD: In other words, you’re

constantly in demand?

Alan Stone: We’re working

all the time. My artists are singing, and

we are keeping them working, so a little bit of income

is going into our treasury to keep us alive.

The problem is that so many of these things come about at

nearly the same time, and we have such a limited number

of singers. For example, our bass Carl Glaum,

who sang with Lyric Opera this season, is our resident bass,

and has appeared with us as Don Pasquale, and Basilio in

The Barber of Seville. He will be working during

the month of March, and I don’t think his poor wife will

get to see him for three weeks between rehearsals and performances.

There are only so many nights in the week, and good basses,

like good tenors and good contraltos are very, very hard to

come by. So those people are really much in demand.

There is a lot of talent around, but in many voice categories

the amount of talent is definitely limited. We would

do our public a big injustice to put someone on who isn’t

ready to do the role, rather than someone who is, even though

they may have been used before. The public agrees, because

they still love to see their favorites in the opera. We

get calls from people asking if Maria Lagios or Robert Orth

in the production, and if we say no, they don’t appear in

that opera because there is no part for them, they’re very disappointed.

They have formed their own fan clubs.

[We then reiterated the dates and times, as well

as ticket prices and availabilities for these performances.]

==========================================================

We now move ahead to December of the same

year, 1979, and pick up the conversation

where we are

talking about the problems of commissioning

a new opera.

BD: Let’s look at it the

other way. If you had the money problems

solved, and you didn’t have to worry about cash, and

all you had to do was worry about the actual opera that

was going to be turned out, what would you ask for?

What would you look for? What kind of guidelines

would you want?

Alan Stone: I would

look for someone with a good eye to the practicality

of producing it. This is not necessarily

just the money, but what kind of demands there are as far

as orchestra size. If it were written for a Richard

Strauss kind of orchestra, I couldn’t do it because I

don’t know where to present it. If that was the case,

I wouldn’t accept the commissioning

money.

BD: [Starting the actual

interview for broadcast, though, as you will see,

we soon slip back into our general discussion] Your

company now is six years old?

Alan Stone: Yes.

BD: What have you learned

in those six years?

Alan Stone: I’ve learned

a lot. For one thing, ultimately the

things that are important in any opera company are

not always the excellence of the performance, but how well

organized you are, and the good strong fiscal backing

you have. I’ve learned that what’s good for the

singers — which

was what prompted me initially to start this company

— isn’t ultimately

of really great interest to the public. If it doesn’t

fit or fill a community need, or if people of the community

don’t need it, the fact that singers need it, means it’s

not important.

BD: What compromises have

you had to make?

Alan Stone: I don’t think

we’ve had to really make any compromises, except

in the choice of repertory, and those have been dictated

by the number of musicians, and so forth. When

I first began my whole experience as a singer and as a coach,

I didn’t realize that you can’t perform La Bohème

with fifteen or twenty musicians, whereas you can perform

The Marriage of Figaro with twenty-four, and have

a very beautiful, effective and very authentic orchestra.

But you can’t do that with many other works, so we’ve

had to make those compromises. There are lots of operas

in the middle repertory I would like very much to do, such as

unusual works of Smetana, or Janáček, and perhaps some

early Puccini as well. [In 1987, the COT would produce

The Two Widows of Smetana, conducted by Pier Giorgio Calabria.]

I might like to take a crack at La Bohème

some time. We might be able to do it with our

small sized theater, but the pit is much too small, which

makes it impossible for the whole latter nineteenth century

repertory, and much of the French opera. [Wistfully]

I’d love to do some Ravel operas.

BD: The double bill of the

two Ravel operas would be nice.

Alan Stone: Right. L’heure

espagnole and L’enfant et les sortilèges.

I would just kill to do that, but there’s no way

that it can done with an orchestra of sixteen players!

Even Massenet and some of those things require a much

bigger orchestra.

BD: So primarily you’re

looking for pieces that will suit the orchestra?

Alan Stone: It’s one

of our most important factors, and the fact that

we don’t have access to large dramatic voices among the

younger singers. It is the same with Lyric Opera, or the

Metropolitan. When I think of singers today that

are singing big roles, no one would have believed that

Renata Scotto would

ever attempt to sing La Gioconda, or

Mirella Freni would sing

Aïda. To me, with my orientation,

that kind of thing is inconceivable.

Even having Roberta Knie do Isolde, you

have the choice of either hearing it with those people, or

you don’t hear it at all!

BD: We’re heading into

1980, and a new decade. Not just your theater,

but where is opera going?

Alan Stone: It’s growing.

There’s no question of that. It’s

going ahead. I have my own theory that eventually

the crunch is going to be with the big theaters.

Unless we find some kind of governmental subsidy,

much more than we have, which is very unlikely, the larger

companies are going to have to start thinking in terms

of cutting down on some of their scope and ideas. They’re

going to have to find more inexpensive and modest ways of

presenting operas, just as they have found more modest choices

of artists, because their bigger and better artists are not

available. Eventually the bigger companies are going

to see that the money to put on these big productions is not

available, and they’re going to find ways of putting on shows

using unit sets, and more projections, and trying to follow

the trend of some of the smaller, more regional companies.

That’s where it’s going to go, but I don’t feel that opera is

in serious danger, because the trend is very, very fast, and

up all over... almost too much in some cases.

BD: Do you resent the record

companies, and their use of a few big stars over

and over again, and the feeling by the public that

if these big stars are not in their casts, it’s not

as good a performance?

Alan Stone: I understand

that, and it’s a very interesting question.

I resent it from a certain point of view.

Rather than resent the record companies in choosing the

same artists over and over, I’m a little bit disappointed

by their artistic standards and values. There

are many fine artists that I don’t feel really should

be documented in certain repertory. Even though they

may want to perform it, or may have performed it, I don’t

feel that the public is wise enough and sophisticated

enough to know who is the best, or who are the best. There

isn’t just one, but several may be among the best. As

a result, generally the public will go with whoever is the

most popular at a particular time. What name have

they heard mostly? It may turn out that the recording

by this artist is a very inferior one. Often it’s

because that role is not really associated with that artist,

and that artist would never have a great success with it because

of the size of their voice, or temperament, and so forth.

You are right, though, when you say many times people get a

pre-conception of what a certain part is supposed to sound like.

Comparisons are odious, and after hearing Sherrill Milnes or Robert

Merrill knock out Figaro in The Barber of

Seville, if someone were to hear our Figaro

they might make some kind of rather negative comparison.

BD: So, it’s two-edged sword.

Recordings have made opera more popular, yet

they have perhaps pushed it a little bit too far

in a wrong direction?

Alan Stone: They have made

it popular and certainly accessible to so many people,

and with the discount record stores, which have become

the rule rather than the exception, more and more people

are buying records in a very unselective way. Records

are what got me into opera. I learned opera and

became involved by listening to records as a young child.

It was Enrico Caruso, and Beniamino Gigli, and Amelita Galli-Curci,

and Kirsten Flagstad that got me interested.

BD: Unless you’re in a

place where you can go to the opera every night,

that’s really the only way you can get a constant and

continual exposure.

Alan Stone: As a young

child, I didn’t have the means of going to hear

them. Caruso had been dead quite a few years by

the time I heard his recordings. [Both laugh]

But in those days, I remember how one would talk

about their Caruso collection, and bring out their

dozen 78 rpm recordings of Caruso as a great treasure.

BD: We’re talking about one

artist recording too many roles. Is the

converse true? Do you feel there have been some

major losses, some things that should have been documented

that have not been?

Alan Stone: Oh, absolutely!

We’ve missed some very good possibilities.

There was never a studio recording of Bidú Sayão

doing Manon. She was the Manon

of our period, and sang it well in to the 1950s,

when recordings were really at their peak.

I remember a great, great Wagnerian mezzo-soprano,

Kerstin Thorborg, who was a great favorite, and who has been

almost forgotten. She was the number

one mezzo at the Metropolitan during the entire Flagstad/Melchior

period. Her performances of Kundry and Brangäne

only survive via broadcast recordings [some of which

have been licensed and issued]. The Brangäne

is on an unofficial recording that the Met gives

you when you give them a contribution. She

was the first Amneris I ever saw. What a shame that we

never got a studio recording of Un Ballo in Maschera

with Zinka Milanov when she was in her prime, though her recording

of Il Trovatore is wonderful. Kirsten Flagstad

was poorly recorded. We missed a lot of chances,

and when they did start to record her, it was already a little

bit late.

BD: When the record companies

start recording a young tenor, or a young baritone,

or a young soprano doing everything, do we then have

the right to complain about that, when we have just

lamented that we did not catch Zinka Milanov or Kirsten

Flagstad early? We seem to be on both sides of the fence.

Alan Stone: Yes, it’s

a mistake to do both things, either too soon or

too late.

BD: Then here’s the question...

How do you know exactly when a singer is in his

or her prime?

Alan Stone: [Thinks a moment]

Well, you don’t ask them. [Both

have a huge laugh] It’s very difficult to answer

that question, because many singers go through

crises during their careers. Had one heard Leontyne

Price singing at the time when she was doing those

famous performances of La Fanciulla del West at

the Met, one would have said that was the end of Miss Price’s

career... and indeed it was for a period of two years.

The same thing happened with Zinka Milanov in the late ’40s,

when she quietly went back to Yugoslavia, and came back

three years later in superb form.

BD: How much of that

would be simply resting the voice?

Alan Stone: A good part

of it is vocal rest, and a re-evaluation of the

voice. It’s interesting to listen to recordings

of singers and how they have changed. It’s

very difficult for a singer to go through a period of vocal

transition, because they are fearful that once they take

themselves out of the market, there will be someone else

to come along, and they’ll be forgotten. I think about

a friend of mine, Grace

Bumbry. When she finally decided

to really make the transition in her mind from mezzo-soprano

to soprano, and not call herself a mezzo-soprano even

though she might still sing a Carmen or an Amneris from

time to time, she had to literally not accept engagements

for at least a year. During that time, she restudied

her voice, and re-evaluated, and reworked on a new technique

of singing. This took enormous courage! Imagine

the courage it takes of an artist who is working and making

money, and who is not in any kind of serious problem.

It’s not like a tenor who decides he’s going to become a baritone

because he’s losing his high notes. This is quite different

because someone is going to tell him to stop. I admire Bumbry,

and I admire other artists who have done the same thing, and

have stopped at a point in their career.

BD: Can it back-fire?

Alan Stone: Yes, there have

been many cases of singers who have stopped,

and then wanted to pick up the career but never quite

picked it up where they had been. Others have

been fortunate in doing so. For example, Carlo Bergonzi.

For a long time there was very little heard

from him. He’s not a young man, at least

not a young man for a tenor. He’s in his middle-fifties

now, and he’s been singing for probably thirty-five

of those fifty-five years. Now he’s quite active at

the Met, and even though he is somewhat limited, he’s still

an artist that has to be dealt with. He still sings

with great style, and with beautiful phrasing.

BD: Where’s the Met’s first

obligation to an artist like Bergonzi, or to the young

artist who is getting started, and beginning

a career, and needing the experience and exposure?

Alan Stone: Of course, they

have to divide their loyalty. Obviously,

they can’t depend on the veteran artists forever, because

they are in some precarious situations. How long

will the high notes ring out as well as they did before?

And when does the moment come when the high notes

don’t ring out at all, or don’t even sound? When the

moment comes that they can’t make a noise at all on the note,

then they have to re-consider their repertory, or reconsider

their vocal range, or just retire and teach in a conservatory!

BD: Are there too many

singers today?

Alan Stone: It’s interesting

that you ask that, and the answer is yes. I’ve

just come back from Opera America auditions. It

was a convention of many of the opera associations

of the United States, including the Metropolitan, San Francisco,

the Lyric, Miami, New York City Opera, and the Chicago

Opera Theater. There were about seventy-five companies

from the whole country, and we heard the final auditions.

They were supposed to be the best young singers that

had been recommended by Opera America companies from all

over the country, and they were there to sing for all the

directors and managers of the opera companies, with the

idea of getting some work. My own feeling was that the

general standard was very low. It seems to me that with

the enormous increase of opera companies, the demand for singers

has increased tremendously.

BD: Is the cream of the

crop being spread too thin?

Alan Stone: The problem is

not that the cream of the crop is being spread

too thin, but the very bottom of the skimmed-milk is

really getting used more than it ever was before.

The small companies can’t afford to have the cream

of the crop, the superstars. So very often young

singers fill those big roles.

BD: I don’t necessarily

mean the superstars, but what about the young

singers who are good?

Alan Stone: Yes, they are

super in demand, absolutely. They are

the ones whose performances in a small company gained

them some distinction, and sometimes in a large company

they are a source of embarrassment. For example,

I’ve heard some very fine young talents with the San

Francisco Spring Opera, and other companies of that size.

I was terribly impressed with them, and I would be very

happy to have them sing with me. But after having

heard them in productions at the Metropolitan and at Lyric

Opera, I’ve been disappointed. They were outclassed.

They were not ready yet for the big, big time.

They were ready for the middle time. Some of these

singers are getting work on the mere fact that they can hit

the notes. For example, we heard a low bass sing Sarastro’s

aria from The Magic Flute.

BD: He had the low F?

Alan Stone: He had the

low F, but that’s all he had. He sang in tune,

but he had no understanding of the nobility, the dignity,

the depth and the breadth of this character.

He was just singing it like a nice song, and yet because

he had the low F, many directors were interested in him

because he could hit that note. It would mean

that they could do a production of The Magic Flute

because they would have someone that can ‘get through’ the

part. That’s all they were worried about. To me,

that’s not enough of a standard. I don’t want a Sarastro

to get through the part. I want him to just thrill

his audience with the role. So this man is going to get

work, but he’s too young to get work. What he needs is

about two years of more study, not just experience. By this

I mean vocal study, language, style, immersion. That man

should be going to Germany and living there, and listening, and

hearing, because when you’re in this business, professional experience

is extraordinary. There’s nothing quite like it, but

there’s a special kind of experience, study experience,

and they’re different.

BD: Have you, as an impresario,

ever asked a singer to do anything that you really

felt, if you were his or her vocal coach, you would have

said no?

Alan Stone: In all conscience

I would say I have not. I have tried almost

pathologically to avoid hurting the young voices.

I was a singer myself, and got myself into terrible

trouble vocally. In fact, for a period of

time, I lost my voice because I was being pushed into a

repertory that I didn’t belong. I was a lyric

tenor, and I sang Mozart and Donizetti, and I was pushed

into heavier Italian repertory, and Wagner because I

was tall. The agents needed those kinds of singers.

I remembered all this very much, and I started the

Chicago Opera Theater. Initially it began because

I was an opera coach, and I was not going to suddenly betray

my standards and my goals!

BD: I just wondered if you

ever found that you had to.

Alan Stone: Sometimes I have

been more persuasive than perhaps I would like to

be, but I never felt that I would offer someone a

role that would do them any physical harm to their voices.

Usually it’s just the opposite. I have to convince

the singers that this particular role is not right for

their voice. Singers are very, very special. They’re

not very objective about their own voices and their own singing.

This accounts for some of the strange things we hear these

days, with artists we love all of a sudden appearing in the

most unlikely roles on television, and in the opera companies.

We ask why they did it, and it’s

because they’re impressionable.

They also feel they need new challenges all the

time. They get tired of doing the same Mimì

over and over.

BD: What about the singers

of the last century, who would have a huge repertoire?

Alan Stone: Many factors

were different in those days. For one, the

size of theater. Obviously, a soprano singing

Tristan and Isolde in a theater that seats

1,500 people as opposed to a theater seating 4,000

makes enormous demands on the voice, including

fighting over a much larger orchestra. Also, the

pitch was considerably lower, so the singers weren’t straining

at the absolute uppermost reaches of their voices.

Despite the fact that we hear stories of Adelina Patti and

all these people who went on forever, most of those people

in the so-called ‘golden age’, had very short careers.

If you look back, when they started talking about Giuditta

Pasta, who created Norma, they talked about her being already

in vocal decline when she sang that role.

BD: But we have no way of

really knowing this.

Alan Stone: Yes, no way

of knowing it except from documentation.

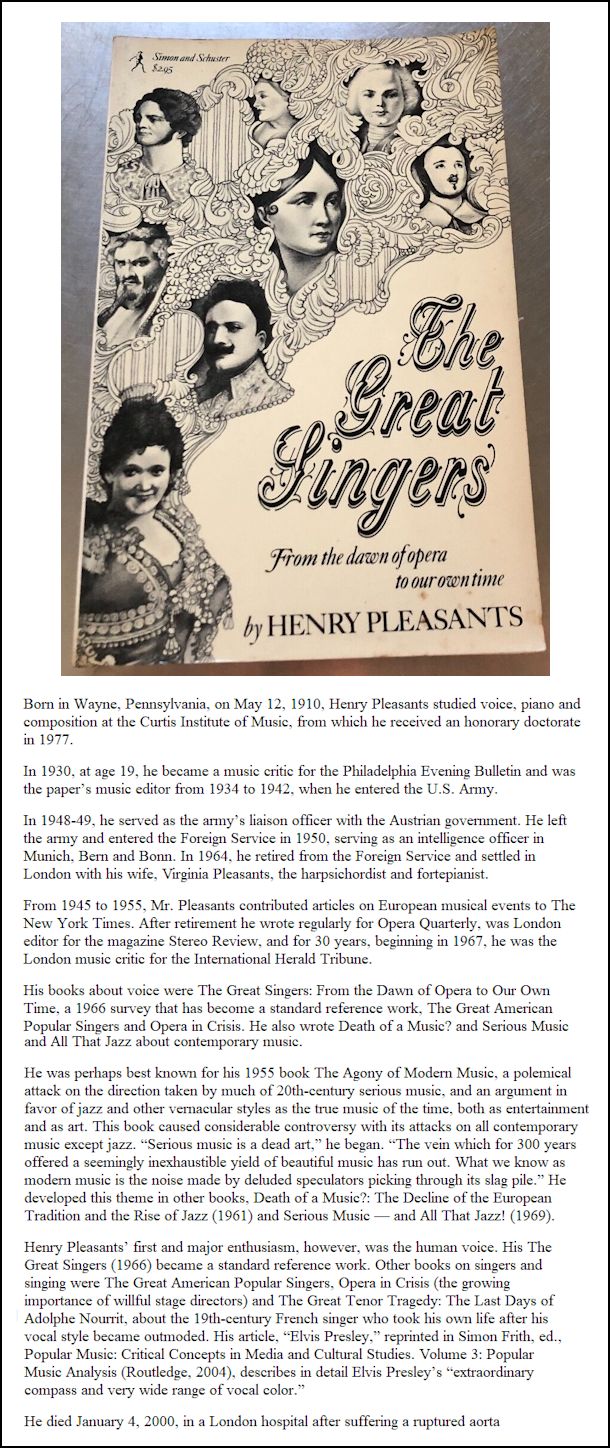

I remember reading about it in Pleasants’ book [shown

at left]. He brings out how the voice was

somewhat in tatters, and the pitch was not so good anymore.

But she was not an old woman. The career of Maria Callas

approximates more the kind of career that existed in the ‘golden

age’. They did everything, and they did incredibly

well, but not for very long. We don’t know

exactly how many of them retired very young, as Callas did.

It’s hard to believe that by the time she was thirty, her

best days were practically over as a singer. This is against

all the rules of physiology because there’s no question

that if a singer is careful and judicious in their repertory,

and if they are technically strong, and keep themselves healthy,

it is not unusual for a singer to sing well into their fifties,

and even as old as sixty. There have been some that go

even longer than that. The deeper voices, the contraltos

and basses last longer. Look at Jerome Hines now. He’s

marvelous.

BD: But they’re not forcing

the upper reaches of the throat.

Alan Stone: They’re forcing

their own upper reaches. A high F for a bass

is just as shattering an experience for a bass

as a high B-Flat is for a tenor, but there is less tension

in it. The emphasis is more on the lower part

of the voice.

BD: A bass doesn’t have

to sing high Fs all the time, whereas the tenor

has to have a lot of B-flats.

Alan Stone: That’s correct,

but there have been some examples... The great tenor

Beniamino Gigli sang like a young man up to four or five

years before his death. There are recordings that

are amazing, not just a recital, but full performances,

and he had sung everything. He had done a huge gamut

of roles, from the lightest lyric leggiero-tenor, all the

way up through to Andrea Chénier, and Radamès,

and Manrico, and Pagliacci.

* * *

* *

BD: Are you happy with opera?

Alan Stone: Am I happy

with opera in general, or with my opera company?

BD: Let’s ask it both ways,

as a patron and as an impresario.

Alan Stone: As a patron, I

must admit not being as happy and not getting the

immense pleasure from opera that I did when I was a young

student. I don’t know if it’s just getting older

and a bit cynical about opera, and sour grapes, and bored

with it, and blasé, but it’s a rare occasion now when

I go to the opera and am really transported into this world

that I lived in as a young singer and young student in Milan

and Chicago and New York. From the other point of view

I understand the reasons for it, but sacrifices have been

made in the standards. I don’t hear the great conductors

conducting opera anymore. When I was living

in New York, I would hear Manon with Pierre Monteux

conducting, and Victoria de los Angeles and Cesare Valletti

singing. In Milan I heard Tosca with Maria Callas,

and Tito Gobbi,

and Giuseppe Di Stefano in his prime, and Tullio

Serafin conducting. So, as a patron I am often

disappointed.

BD: But now you’re in a

unique position, because you are sometimes a patron,

and sometimes an impresario. Is there anything

that you are doing, or are there lots of things that

you are doing as an impresario, simply to make patrons more

satisfied?

Alan Stone: It’s interesting,

and I’ve often wondered about this. I love

my performances! I just think that the Chicago

Opera Theater performances are wonderful.

BD: But you’ve molded them

to your taste.

Alan Stone: That very well may

be part of it, and also because I go to those performances

not expecting the kind of perfection and the superior

state of the art that I do expect from the Metropolitan

Opera and the Lyric Opera productions. I go to my

productions looking for entertainment and music theater.

I know already that I’m not going to hear Luciano Pavarotti.

I’m not going to hear Birgit Nilsson,

and Joan

Sutherland. So, my whole expectation

is considerably different.

BD: What would happen if

you went to the Lyric Opera, or the Met, with those

kinds of expectations?

Alan Stone: When I have gone

like that, then generally I’m not disappointed.

It depends a lot on the repertory. For

example, when I went to the Lyric to see The Love

for Three Oranges, I knew from the nature of the

work that I was not going to get a display of individual

vocal skill. I knew it was being done in English.

I knew the singers were mostly younger American singers.

I went to see a spectacle, rather than one of my old

favorite operas. Then I wasn’t disappointed. You’re

right, I came with a different set of values.

But when I go to hear Andrea Chénier or La

Bohème at the Lyric, I have too many memories

in my ears of people I have heard over the years,

and there aren’t too many people singing these parts today

that are going to make you erase those memories. They

tell you that’s a sign of getting old when you start feeling

this way.

BD: It seems that every

age is that way. People who have been going

to opera for twenty, thirty, forty years, begin to

only remember the performances of twenty, thirty, forty

years ago, whereas the young goers are remembering performances

only from last year, or the year before. So they’re

perhaps more satisfied with what they’re hearing.

Alan Stone: That may very well

be. Although because of the enormous immersion

in opera that so many people have, it is hard to gain

a sense of what is the best. In the early days before

there were so many recordings of so many things, one knew

about Kirsten Flagstad. She sang almost all of

the Wagner roles, and made a few recordings.

BD: Then were people disappointed

later when they heard Astrid Varnay or Helen

Traubel?

Alan Stone: Perhaps if

they had heard them at the time, if their careers

had been contemporary, they might have been somewhat

disappointed. Astrid Varnay’s career perhaps did

suffer, and Helen Traubel’s career suffered, although she

had a huge career. But now there are so many more

singers appearing on recordings, and so many people have recorded

the same work. There are too many recordings for

my money of the same opera. I don’t know why we need all

those, except to sell more records. What’s even more

confusing is when someone has recorded the same role twice.

It’s interesting from a documentary point of view, for a

musicologist or a vocal pedagogue to compare one recording to

the next one he made five years later, but I don’t think the audiences

get into that aspect of it at all.

BD: How many different

opera audiences are there, or are there are as many

audiences as there are people who go? [Vis-à-vis

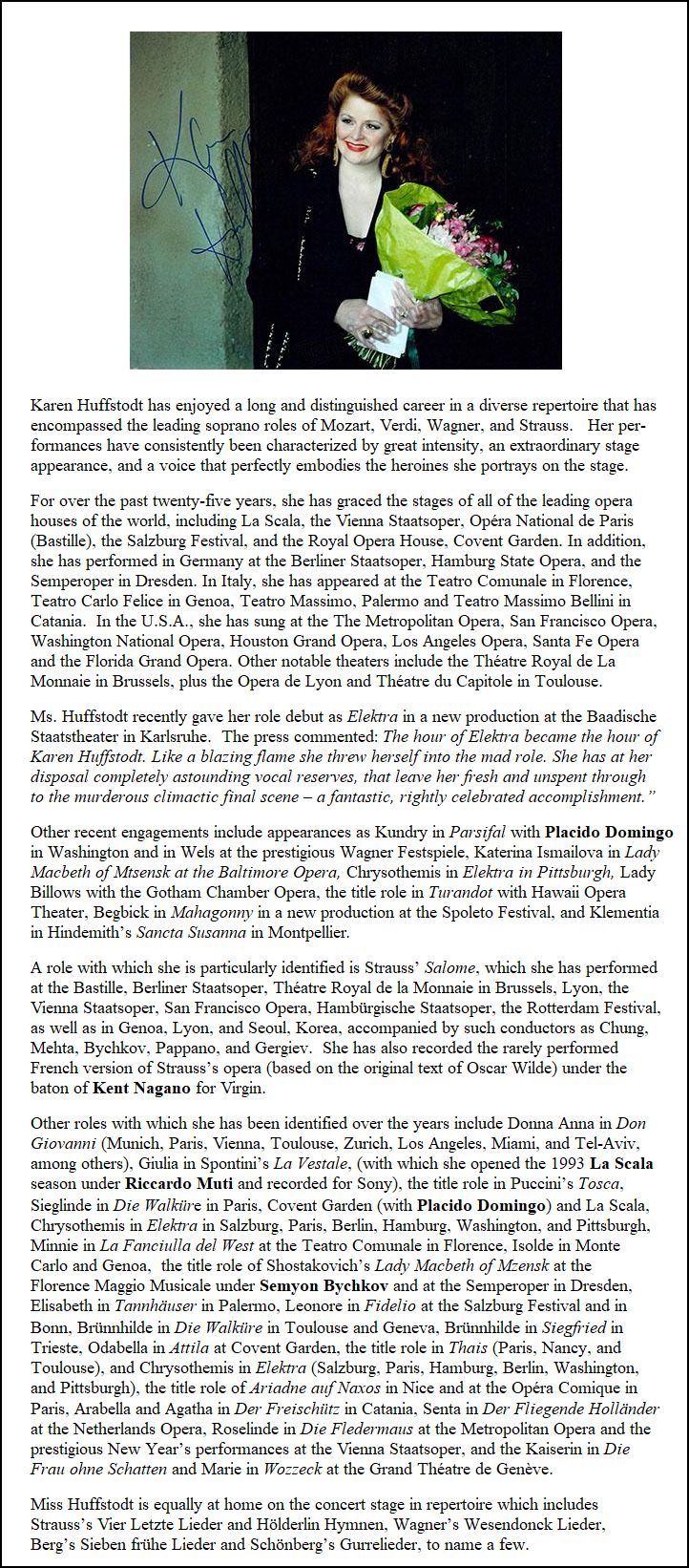

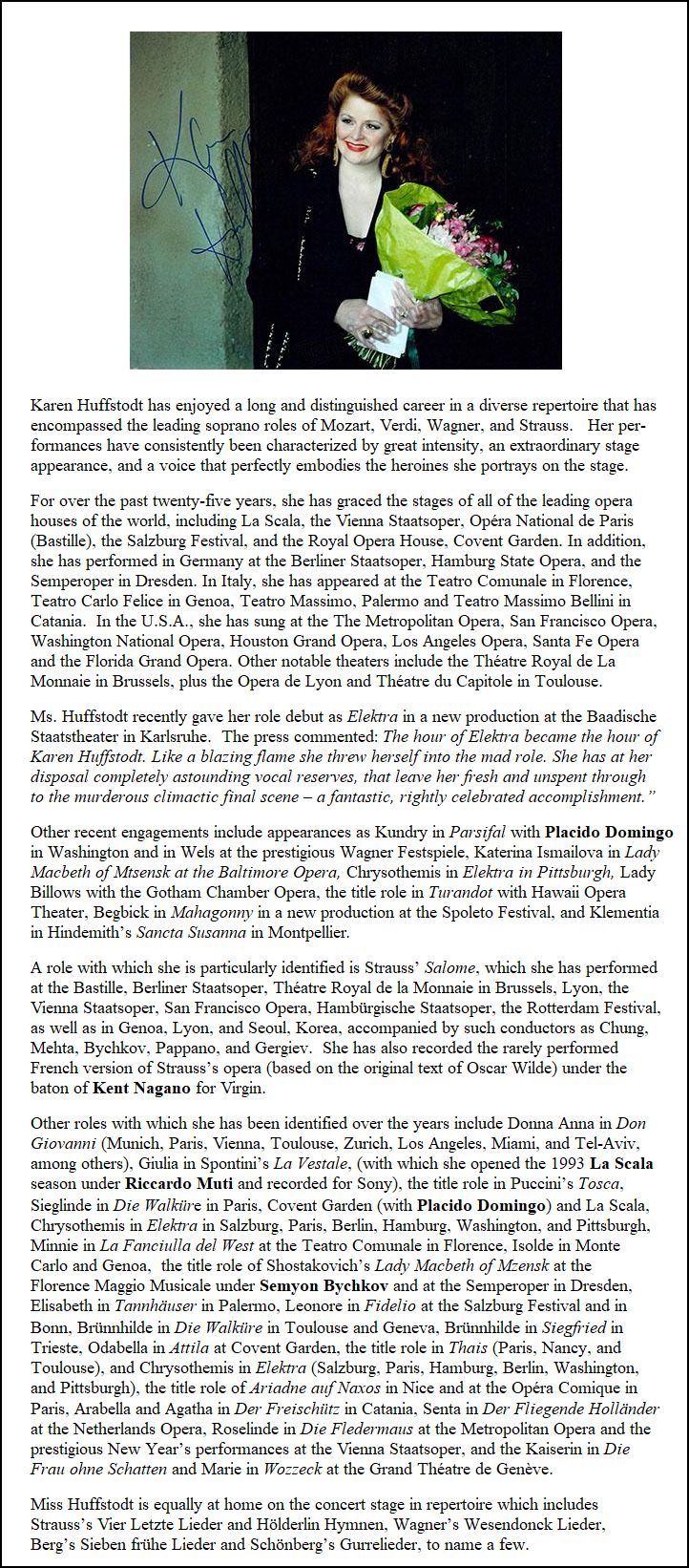

the biography of Karen Huffstodt shown at right, see my interviews

with Zubin Mehta, Semyon Bychkov, and Antonio Pappano.]

Alan Stone: I don’t think

I could define how many audiences there are. [Pauses

a moment] It’s the first time you’ve ever

talked to me about these things! It’s interesting

that you mentioned me as a singer turned impresario,

because that was brought out at the Opera America meeting.

Here we had all these people from all over, but of

all the artistic directors, or managers, the orientation

for most of them was not in the singing. There were

only three that came from a singing career.

BD: The rest were from

the business world?

Alan Stone: No, most

of them came either from the stage, as stage directors,

or they were conductors. In the little companies,

many of the artistic directors conduct the orchestras.

The only people who came from the singing world

were Beverly Sills, and David Lloyd,

and myself.

[At this point we promoted La Périchole

with details of performance dates and times.]

=========================================================

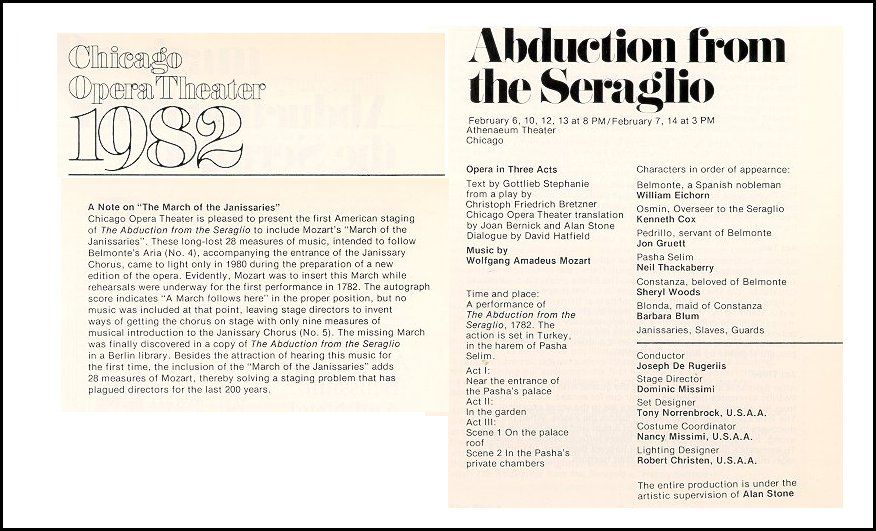

Now we move along to

February of 1983.

BD: It’s my pleasure to

be speaking once again with Alan Stone, the founder

and artistic director of the Chicago Opera Theater,

which is embarking on its ninth season. There

will be three operas in this particular season

— Martha by Flotow,

The Consul by Menotti, who will

be in town to direct his work, and also The Barber

of Seville by Rossini. Why Martha?

Alan Stone: Why not Martha?

It was for so many years one of the standards

in the repertory, and one of the most popular of all

the grand operas. I remember seeing the Mario

Lanza movie, The Great Caruso, with music of Martha.

Then in the last thirty or forty years it’s

gone very much into obscurity, and has been neglected.

I really think it’s due to the fact that it’s devilishly

difficult to do. It’s much harder than it seems.

It calls for a cast of virtuoso voices, wonderfully attractive

people, and a big chorus. Perhaps twenty or thirty

years ago we were too cynical to enjoy some of the sentimentality

and romanticism, but the wheel is turning now, and people

are ready to enjoy shows like that just like movies such as Tootsie

and things of that kind. We need some of that fresh air

in this ugly atmosphere that we’re living in, and that’s why

I picked Martha to do.

BD: Is this one of several

that you have in mind, little plums, little gems

that you’re sprinkle season after season?

Alan Stone: Yes, it’s something

I have been trying to do, and quite successfully

over the years, ever since we started doing three

operas. We’ve done, for example, The Daughter

of the Regiment, which is hardly ever done. It

was only done once by Lyric Opera in almost thirty years of

its history. We’ve also done La Périchole,

and La Rondine, The Italian Girl in Algiers,

and The Abduction from the Seraglio. These

are not frequently performed operas, and yet they are the works

that everybody knows, but nobody’s seen lately. The

Pearl Fishers is another one that we’ve done which is very

much forgotten on the stage. It has a beautiful score,

and one that the public knows a lot from recordings of excerpts.

My problem is to keep digging these things up and not digging

myself under the ground while I’m doing it! [Both laugh]

BD: This seems to be the

pattern of your season. You do one favorite,

one middle romantic novelty, and then one contemporary

theater piece, and it provides a balanced season.

Alan Stone: That’s a formula

I devised back in 1979 when we went into three

productions, and so far we’ve been able to continue

it. I hope we will be able to follow this device,

because it offers something for everybody. It’s

good training for the audiences, and good training also for

the artists to get a chance to work in different genres of opera.

BD: Tell us a little bit about

Martha.

Alan Stone: It might be

called the counterpart to Così Fan

Tutte. In this opera we have two men and two

women. The women in this case are aristocratic,

or represent the aristocracy, as they do in Così,

except that in this story, they get into costumes and go

into a new environment. They pick up these two farmer

boys, thinking they’re going to have a little fun.

But the plot gets a little rough, because the boys are quite

serious about this romance. It turns out that one

of the boys isn’t really a farmer, but an aristocrat in disguise.

After all the complications and ramifications of the plot,

of course it all turns out happily ever after at the

end, accompanied by glorious music. The famous ‘M’appari’

is the tenor aria that everyone knows.

BD: How does that translate?

Alan Stone: In this particular

translation, I believe it says ‘Like in a

dream, I think of you at night’. I may not have

all the words right, but it’s a very easy translation to

sing, and quite close to the original ‘Ach! So Fromm’.

‘M’appari’

was a translation because the opera was originally written

in German. So here we have a German composer

writing about England in the beginning of the eighteenth

century, and being most famous in its Italian translation.

There’s as little song called ‘Qui Sola Vergine Rosa’

which we know better in English as ‘The Last Rose of Summer’.

Many people don’t know it was used in Martha.

[It’s an Irish poem from 1805 by Thomas Moore, and the tune

goes back to 1792. So the music for this number was arranged

by Flotow.] There’s also beautiful

ensemble music, quartets and quintets.

BD: You say it’s very difficult,

but is it fun to work with?

Alan Stone: Oh, it’s marvelous

fun. It’s difficult technically, and yet

it mustn’t sound difficult. The pyrotechnics

are all concealed in the lightness and romanticism of the

work. Particularly on the part of the tenor and the

soprano, it calls for very, very difficult singing.

There’s very high tessitura

for the tenor, and a very extended range for the soprano,

with numerous high Ds and E-Flats. The contralto

is the sort of voice of Verdi called ‘mezzo

soprano’. She

should be able to sing Azucena or Amneris with the

personality of a Rosina. Dramatically it’s a soubrette

role, but it cannot be sung by a light soubrette

lyric mezzo soprano. Instead, it needs a really full

mezzo-contralto. The baritone or bass is another

wide-ranged role, a big, almost like a Heldenbariton,

from a low F to a high F, with sustained notes,

too. All of these parts are very, very difficult.

BD: Was it very difficult

to cast this opera?

Alan Stone: It was difficult,

except that fortunately over the years I have

built up a wonderful stable of great vocal artists.

They are young, but still wonderfully talented.

Generally, I always have an idea of someone in mind

for at least some of the major parts. One of the

reasons I decided to do Martha was because I had

worked with Karen Huffstodt, who had done La Rondine

with us, and also the previous Così Fan Tutte.

I knew her voice, having worked with her and coached

with her. I felt she was the right soprano. She

had the extension on the top that you could work with.

Also, the tenor, Richard

Leech, had sung in our production of La Rondine

with Karen, and they were very beautiful together. They

sing so well together that I knew if I could cast the tenor and

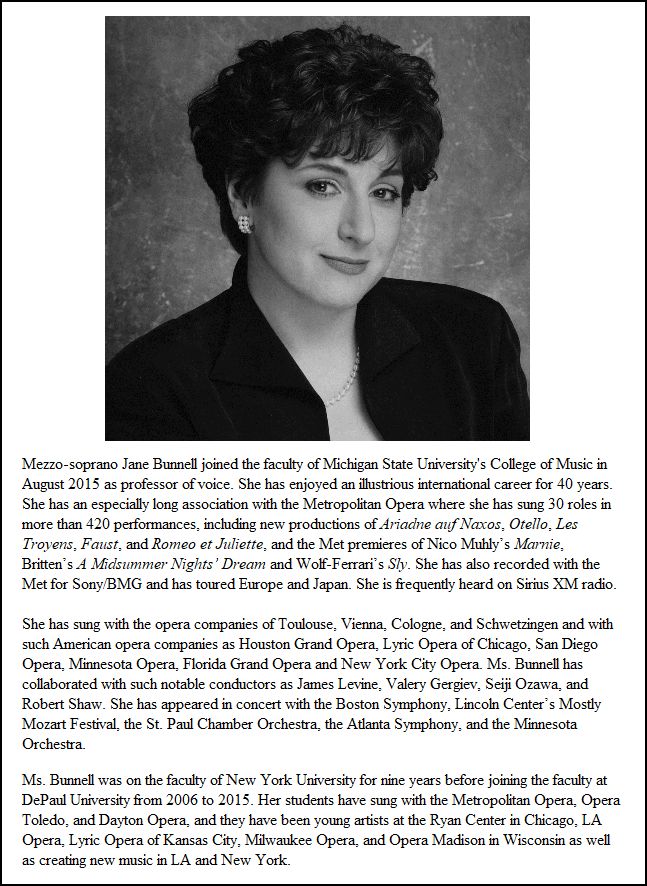

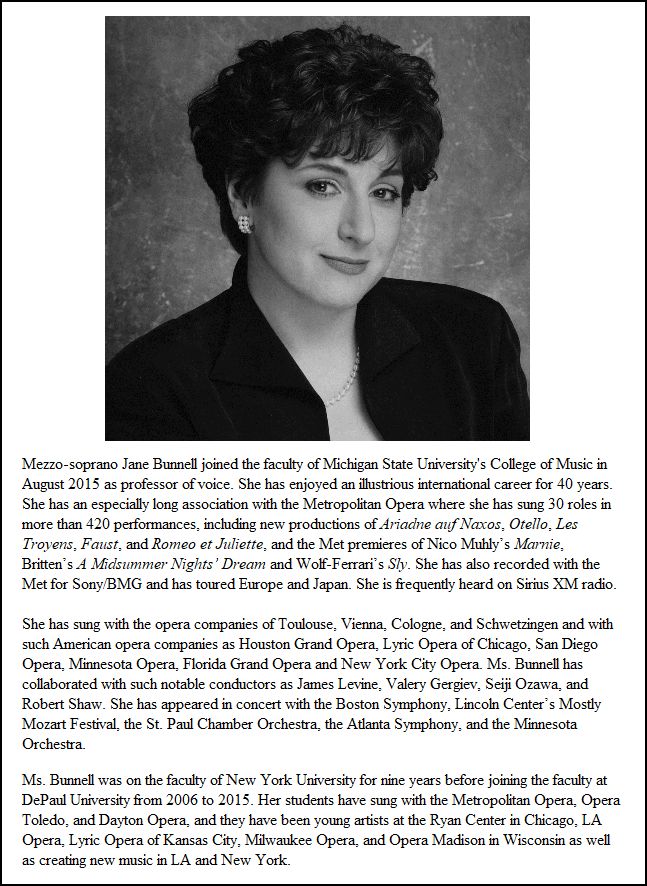

the soprano, I could go ahead. The mezzo soprano, Jane

Bunnell*, is the only one who is completely new to the company.

I cast her from New York. She has just the most

beautiful and wonderful rich deep contralto voice, and yet there’s

no resemblance to a contralto who sings ‘O Rest in the Lord’, or

‘O Thou that tellest good Tidings to Zion’. She’s a perky girl

with a big huge perky voice, and it’s wonderful. The

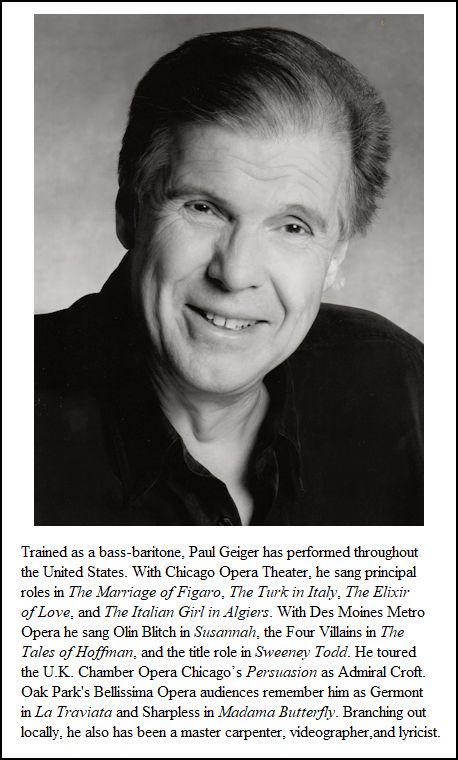

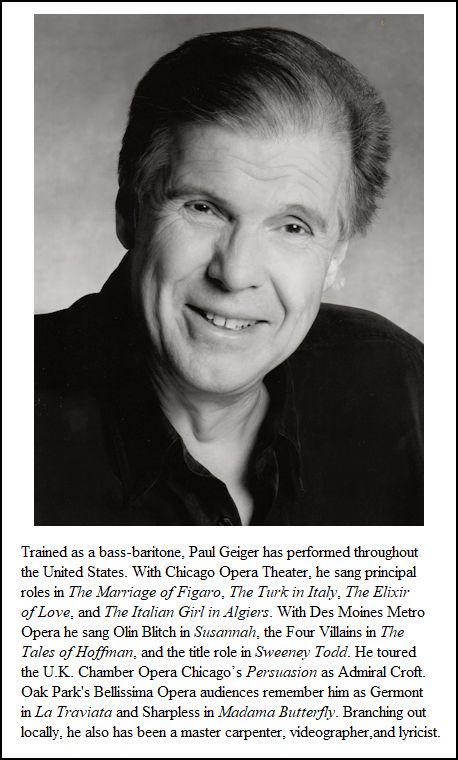

bass, Paul Geiger*, has done Figaro with us before, and The

Italian Girl in Algiers. The character he plays, Plunkett,

is a farmer in the story, and Paul lives in Iowa and is kind of

a farmer boy himself. He’s

6 feet 5 inches! I had the cast pretty well in mind.

The big question was the mezzo, and when I found her, we were

all set.

BD: Are there some little

roles in the opera?

Alan Stone: There are two, and

they’re not little. There’s one quite a big

juicy supporting role in the role of Sir Tristram Mickleford,

who is the suitor and cousin to Martha, or Lady Harriett.

It’s a basso-buffo part, which is being done by William

Walker*, who has just come back from a year with the Zurich

Opera. He sang with us in The Good Soldier Schweik,

and has done Don Basilio in our tour of The Barber of Seville.

The other small but very important part is the Sheriff.

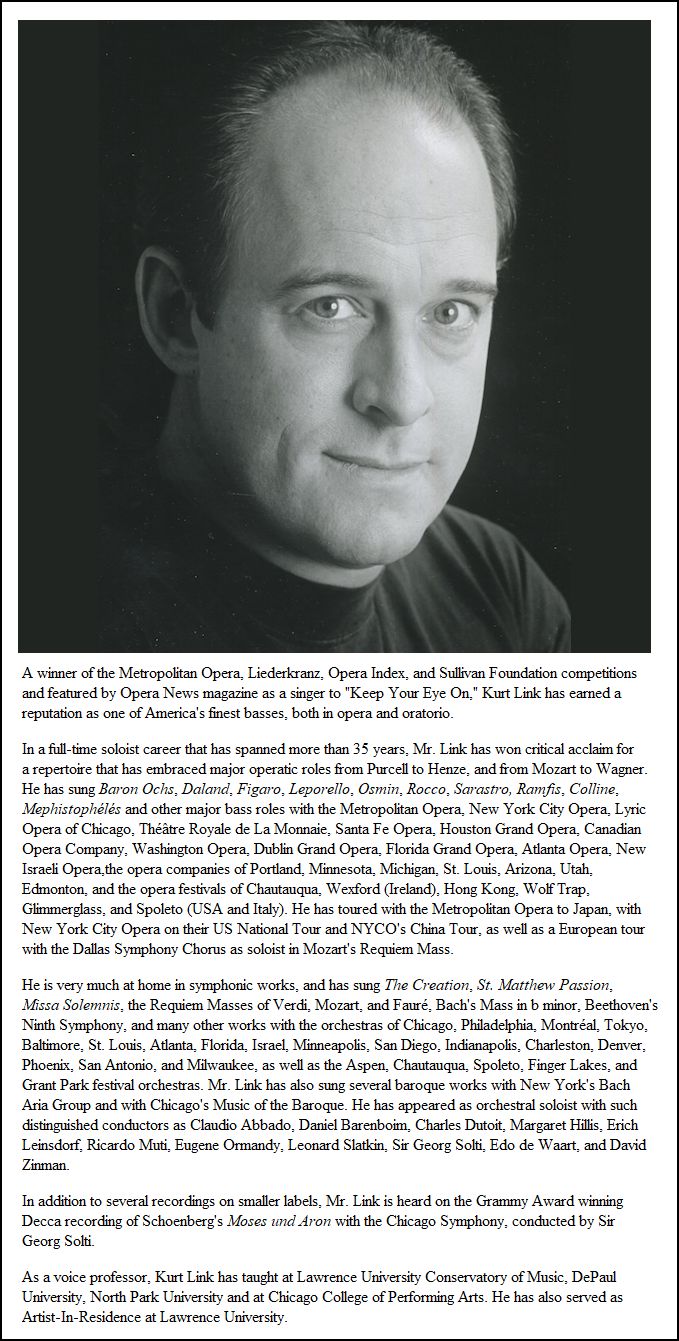

He only sings in one scene, but that’s the role in which Paul Plishka made his

debut at the Met back in the ’60s.

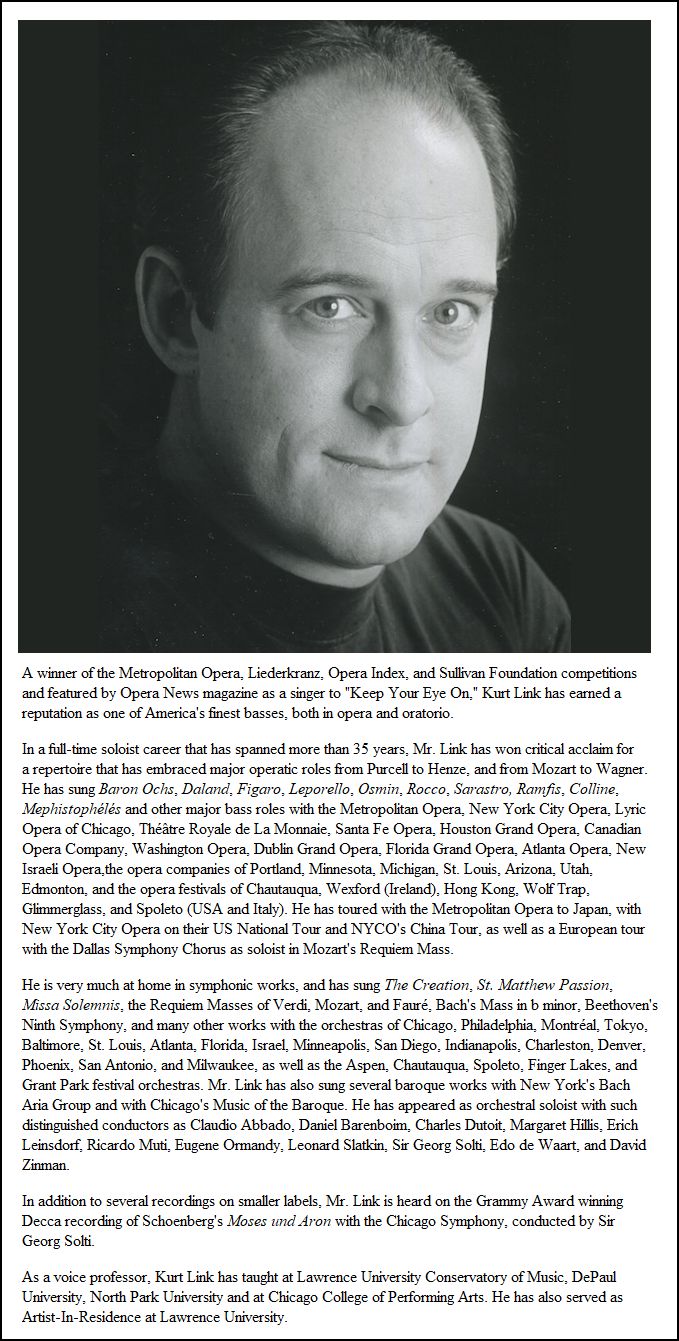

That is being sung by Kurt Link*, who has

sung with the Chicago Symphony and Georg Solti, and is

now beginning his operatic career. He has a wonderful

voice, and although it’s a small part, I heard him

in rehearsal today, and it was a big noise! [Both

laugh]

BD: Who’s the conductor?

Alan Stone: Conducting

will be our regular conductor, Steven Larsen,

who last year did such a wonderful job

with our Regina, and the year before he

led an incredible production, one of the things I’m probably

proudest we ever did, The Good Soldier Schweik.

[Twenty years later (2001), the COT would again

present this opera, conducted by Alexander Platt, and directed

by Harry

Silverstein, with sets by John Conklin.

It was also (audio) recorded at that time as a

two-CD set.] Steve has been doing a lot of contemporary

music, and I decided to give him a break this season and

let him try a different kind of music. That’s why he’s

not conducting The Consul, but he is conducting Martha.

BD: I had expected him

to do The Consul.

Alan Stone: Yes, everyone

did, and he did too, but his experience has

been primarily in symphonic and orchestral conducting,

as opposed to opera. There’s not that much opportunity

for young people to conduct opera. He had a real

feel for orchestra, and Martha [1847] is very Germanic,

in its own way. The influence of Weber is very strong,

and you can hear early Wagner all over the place. Not Tristan

or the Ring, but there are choruses that sound right

out of The Flying Dutchman [1841]. The Farmers’

Chorus has that wonderful rousing beat and rhythm and vigor

that we hear in Wagner’s very

early opera Rienzi [1840]. So, that’s why I was sure,

and I’m even more sure having heard the rehearsals, that Steve

will bring all of that sound out of the orchestra, and the chorus,

and singers as well. [The production would open a few days

after this broadcast.]

BD: Everything always seems

to work in your productions. Even as you go

into the last couple of rehearsals, and you’re worried

about this and that, you always seem to bring it off

well. Tell us about the other operas you will be presenting

later in this season.

Alan Stone: You mentioned

The Consul [winner of the 1950 Pulitzer

Prize for Music], and the biggest coup we have this

year is that I was able to persuade Menotti to come and direct

his own opera, which has never received a professional production

in Chicago. It is a great honor and thrill and treat

for us to have the great man here. I worked with

him many years ago very briefly in Tamu-Tamu [1973].

I was the casting consultant, which meant I set up all

the auditions, and did the preliminary auditions for the singers

for that opera. You will recall that I did have my

training in Italy, and I lived there for three years, so I speak

the language quite fluently. Although Menotti

was born in Italy, he prefers to speak in English, and

for his operas he writes his own librettos, and he writes them

in English. He doesn’t translate. The only opera

he wrote in Italian was Amelia al ballo [Amelia Goes

to the Ball].

BD: That was a very early

work [1936].

Alan Stone: Yes, an early,

early work. But even though he prefers

to speak English, he speaks Italian fluently, and

he does have a slight accent. He was in his early

twenties when he came over from Italy, but it’s wonderful

to be able to speak to him in Italian because we have

all these little secrets going on. We can say

these terrible things about everybody, and nobody knows

what we’re saying... at least we hope they don’t! [Both

laugh]

BD: Is the casting for The

Consul complete now?

Alan Stone: Absolutely,

and it’s a wonderful cast. This is our richest

year of casting. When you see the names of

the people, you might wonder what happened to all the Chicago

singers, and I must say that I did get the majority

of the leading singers for The Consul from the

New York area. That was partially due to the

fact that Menotti wanted to be in on all the auditions himself

with me, and at least be able to agree together on

who we would choose. I had four series of auditions

in New York with him before we finally fixed on our artists.

So, most of the leading people in the big roles are from

New York. The smaller roles, the supporting roles,

are important, and most of those are from Chicago. Then,

the Barber of Seville has a good mix. As Figaro,

we have our veteran star, Robert Orth, who is singing all over

this country. He was so wonderful as John Buchanan

in Summer & Smoke on television this last year.

His Rosina is Cynthia

Munzer, who is formerly of the Met and sings all over

the country and all over the world. She did The Italian

Girl in Algiers. The tenor is Abraham Morales,

a wonderful leggiero tenor, of which there are so few, because

most tenors get tired of singing Rossini. They want to

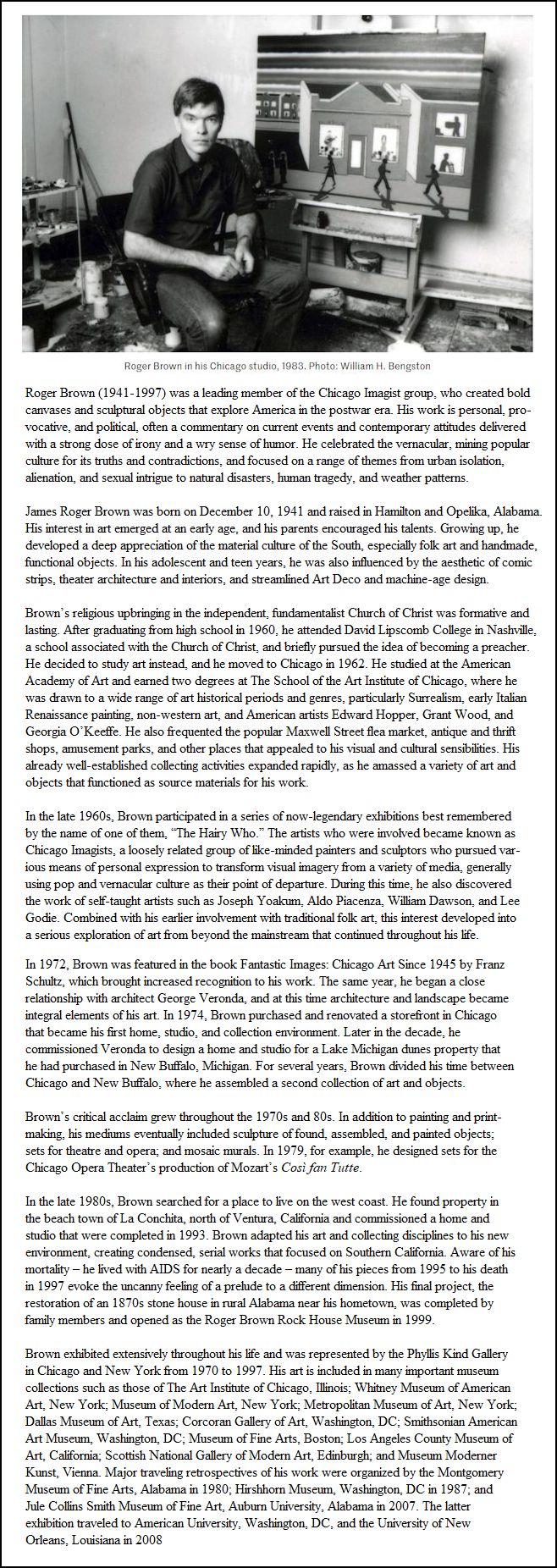

sing bigger things, and then when they want to go back to the

good old bel canto leggiero stuff, they can’t

do it anymore. There are very few of them that have

learned the lesson of Alfredo Kraus, and

who is still singing amazingly and beautifully well. The

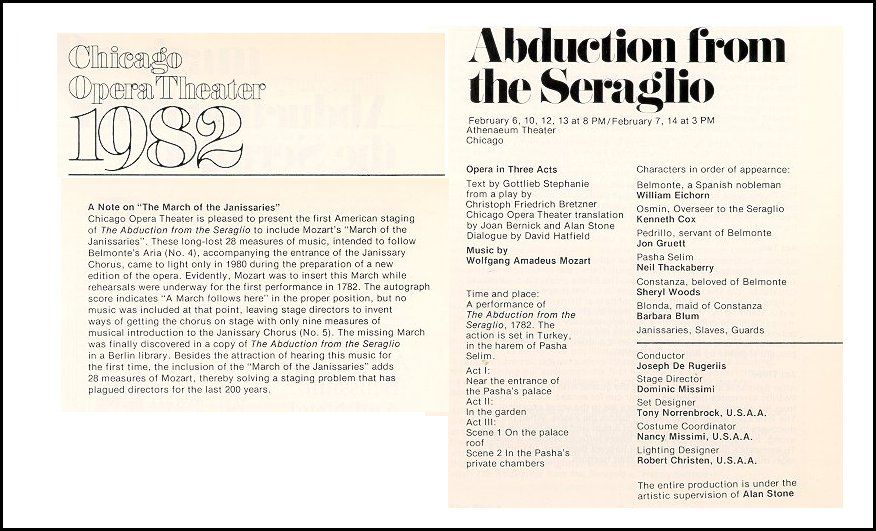

basses are Kenneth Cox, who was our Osmin, and Carl Glaum,

who did Pasquale with us. Glaum did Basilio in our

first Barber, and he’s now a staple at the San Francisco

Opera, where he’s done some wonderful roles. They love

him there, and now he’s coming back to sing Bartolo.

He always wanted to do Bartolo, and physically he’s small

and bit husky, which is really physically much more for my

taste as Bartolo. For Basilio I prefer to have a slender

taller man. Carl is able to handle that terribly difficult

tessitura of Bartolo. It’s a very difficult role, maybe

the most difficult role in the whole opera. People don’t

always realize that because he is covered up with a load of jokes,

and is asked to do funny things with the voice. I should

also mention our conductors too and directors. Our director

for Martha is Dominic Missimi,

a local director, teacher and professor at Northwestern,

and one of the most incredible young operatic directors. He

is not only a director, he’s a musician, and he can

breathe life into most scores that are very difficult.

He did La Rondine for us, and The Italian Girl

in Algiers, and Seraglio. That’s already

something because there’s very little action, but Dominic

can extract much from it. In The Consul,

our conductor will be Joseph De Ruggieriis,

who conducted our Seraglio last year.

He is the conductor of the San Diego Opera and

also San Francisco Opera. He worked with Menotti

in Spoletto, Italy, years ago as his assistant, and he

asked me not to do a classic this year. He wanted to do

a contemporary opera, so it worked out. Larsen,

who had done the contemporary one, wanted to do the

classic, and so we made a nice switch. Nicholas Muni

will direct Barber. He is from New York, and is a

director who’s trained in music. He’s been very helpful

to me in working out recitatives. The conductor is a wonderfully

bright young man whose operatic career has been going wild

in this country, Mark

Flint. He is from the Michigan Opera, and has also conducted

the St. Louis Opera and the San Francisco Opera Spring Opera.

He’s probably the busiest young American opera conductor,

and so we have quite a team.

[At this point we listed dates and times for the

radio audience. We then continued chatting privately

about other operatic subjects, including the use

and mis-use of recordings.]

Alan Stone: Young singers always

like to get a recording to help them.

BD: To crib from! [Both

laugh] [Vis-à-vis the biography of William

Walker shown at right, see my interviews with Eve Queler, John Rutter, Thomas Wikman (Founder

of Music of the Baroque), and Margaret Hillis (Founder

of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.]

Alan Stone: Yes, sure. I

just wonder what people did before those days.

To me, the recordings and tapes are so important, not

to copy but just to get a feeling of the work. I hear

singers say they’ve enjoyed them because this is their passion,

too. But I hear some conductors say they

never listen to recordings, or they never listen to their

own recordings. They can give you a point of view, but

they want to do it fresh. Steve said that to me one

time, and I told him he should have listened to it because his

tempo was completely wrong dramatically. It was just

off a hundred per cent. This was not in Martha,

but rather was some years ago. He had learned a little

bit since. About four years ago I was in Italy,

and I went to visit my old friend (conductor) Giuseppe Patanè.

I stayed at his home, in his villa. He lives

in Milan and has a villa up in the mountains with a beautiful swimming

pool, and a garden. He loves animals, and he’s got all kinds

of monkeys. Even though he had invited me, I practically never

saw him because he was going to be doing a production of The

Flying Dutchman in Vienna. He was studying, studying,

studying. This was his vacation, but he said that he’s

got to prepare. One day he called to me and said he was sorry

he was spending so little time with me. I was there for four

days, but we only saw each other at meal times, once in a while.

He said, “They want to kill me in

Vienna because I’m Italian. They don’t think anybody

can play Wagner but the Germans. But I will not let

them kill me! I am preparing for this so much.”

In his studio he has wonderful sound equipment, and he asked

me to listen to something. “Is there too

much portamento? No? What do you think?”

I asked who it was, and he said it was Gwyneth Jones.

Then we listened to Kirsten Flagstad.

He also played Furtwängler and said,

“He has it all. He gets

everything, and he hears everything.”

Today it’s like wine-tasting. One