| Bernhard Heiden (b.

Frankfurt-am-Main, August 24, 1910; d. Bloomington, IN, April 30, 2000)

was a German-American composer and music teacher, who studied under and

was heavily influenced by Paul Hindemith. The son of Ernst Levi and

Martha (Heiden-Heimer), he was originally named Bernhard Levi, but he

later changed his name. Heiden quickly became interested in music, composing his first pieces when he was six. When he began formal music lessons he learned music theory in addition to three instruments - piano, clarinet, and violin. Heiden entered the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin in 1929 at the age of nineteen and studied music composition under Paul Hindemith, the leading German composer of his day. His last year at the Hochschule brought him the Mendelssohn Prize in Composition. In 1934 Heiden married Cola de Joncheere, a former student at the Hochschule that had been in his class, and in 1935 they emigrated to Detroit to leave Nazi Germany. Heiden taught on the staff of the Art Center Music School for eight years. During his teaching career he conducted the Detroit Chamber Orchestra in addition to giving piano, harpsichord, and general chamber music recitals. After having been naturalized as a United States citizen in 1941 he entered the army in 1943 to become an Assistant Bandmaster. After the close of World War II he entered Cornell University and received his M.A. two years later. He then joined the staff of the Indiana University School of Music, where he served as chair of the composition department until 1974. He remained composing music up until his death at the age of 89 in 2000. Heiden's music is described by Nicolas Slonimsky as "neoclassical in its formal structure, and strongly polyphonic in texture; it is distinguished also by its impeccable formal balance and effective instrumentation." Much of Heiden's music is for either wind or string chamber groups or solo instruments with piano. He also wrote two symphonies, an opera, The Darkened City, a ballet, Dreamers on a Slack Wire, and vocal and incidental music for poetry and several of Shakespeare's plays. His notable students include Donald Erb and Frederick A. Fox. [See Bruce Duffie's Interview with Donald Erb.] |

BH: A lot! He

was an incredible musician and teacher. I must say he was a tough

teacher; rather he showed mostly what you would call technique of

composition. For the first two years when you studied with

him, he was not interested at all in your own composition, but simply

wanted to equip you. That was 1929 in Berlin, and he concentrated

on really doing counterpoint, which we did for two years or so!

BH: A lot! He

was an incredible musician and teacher. I must say he was a tough

teacher; rather he showed mostly what you would call technique of

composition. For the first two years when you studied with

him, he was not interested at all in your own composition, but simply

wanted to equip you. That was 1929 in Berlin, and he concentrated

on really doing counterpoint, which we did for two years or so! BH: Oh, sure!

Yes. In fact every performance of any piece is really

different. Every performer will discover things. What makes

the life of a composer interesting is to listen to different

interpretations of a piece of his or hers.

BH: Oh, sure!

Yes. In fact every performance of any piece is really

different. Every performer will discover things. What makes

the life of a composer interesting is to listen to different

interpretations of a piece of his or hers. BD: They apply to

your music collectively, then?

BD: They apply to

your music collectively, then? BH: That was a time

where radio stations had symphony orchestras. The music director

was an excellent pianist, so he knew mainly piano literature which he

wanted me to transcribe for orchestra. That job is not always the

easiest if the music is very pianistic. That’s all a commercial

situation. It’s a job where you get an assignment on Monday and

they say, “Can you have it for Thursday’s program?” You really

sat up all night, and that was before Xerox! We were sometimes

involved making parts, and all that. So that was

interesting. [Laughs]

BH: That was a time

where radio stations had symphony orchestras. The music director

was an excellent pianist, so he knew mainly piano literature which he

wanted me to transcribe for orchestra. That job is not always the

easiest if the music is very pianistic. That’s all a commercial

situation. It’s a job where you get an assignment on Monday and

they say, “Can you have it for Thursday’s program?” You really

sat up all night, and that was before Xerox! We were sometimes

involved making parts, and all that. So that was

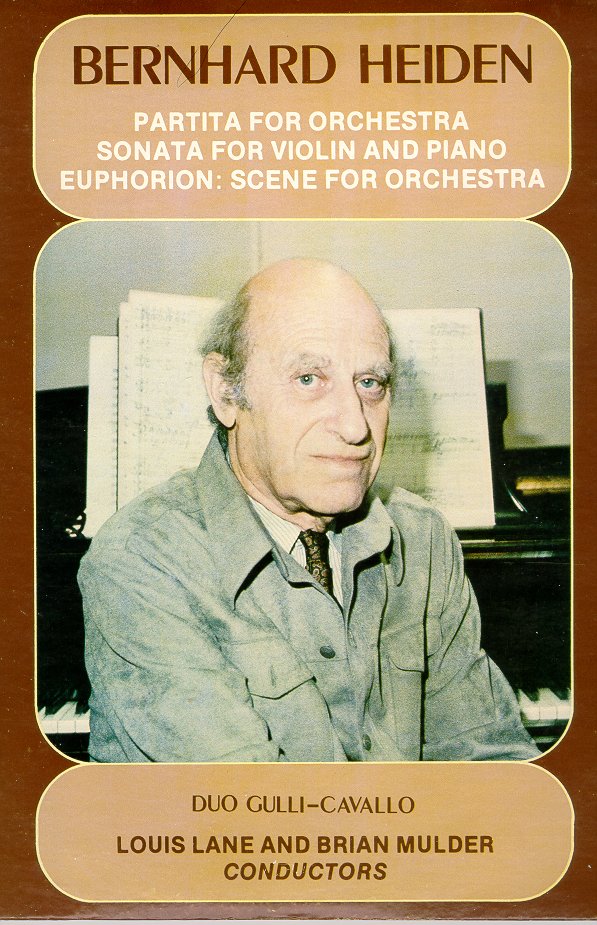

interesting. [Laughs] BD: You sent me one

record that has the Partita for

Orchestra, the Sonata for

Viola and Piano, and Euphorion,

which was once performed here in Chicago by the Chicago Symphony under

Fritz Reiner in 1956.

BD: You sent me one

record that has the Partita for

Orchestra, the Sonata for

Viola and Piano, and Euphorion,

which was once performed here in Chicago by the Chicago Symphony under

Fritz Reiner in 1956. BD: What about the

program we’ll do on the radio — ninety

minutes exploring some of your music with some of our talk?

BD: What about the

program we’ll do on the radio — ninety

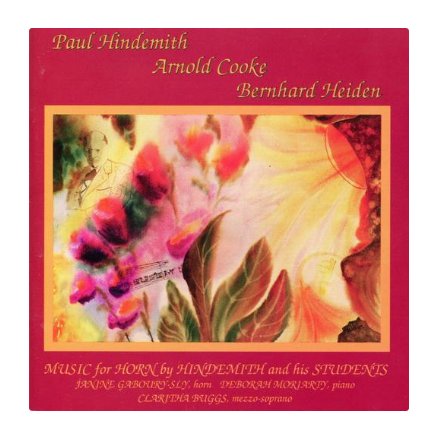

minutes exploring some of your music with some of our talk? BH: Some pieces have

lasted. For instance, there’s two pieces which are now somewhat

standard. They are earlier pieces. One is a horn sonata and

one is a saxophone sonata. I would say most people who study

classical saxophone have played it now for almost fifty years.

The same is true for the horn sonata.

BH: Some pieces have

lasted. For instance, there’s two pieces which are now somewhat

standard. They are earlier pieces. One is a horn sonata and

one is a saxophone sonata. I would say most people who study

classical saxophone have played it now for almost fifty years.

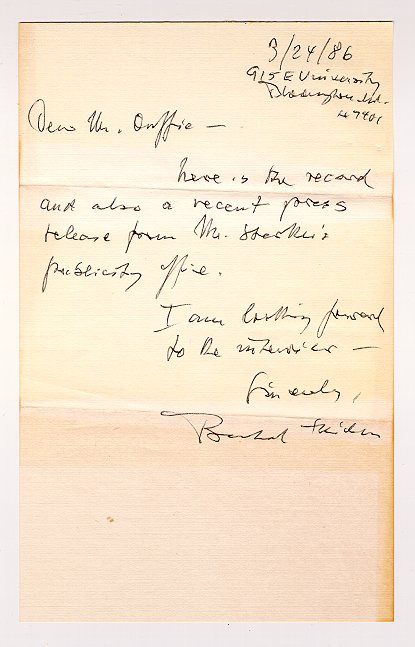

The same is true for the horn sonata.This interview was recorded on the telephone on April 19,

1986. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB later that year, and again in 1990, 1995 and 2000. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.