János Starker: To glories,

further glories. Of course, when anybody asks me this question, there

are always two ways I answer it. One of my writings deals with the

fact that in the twenty-first century, music may be outlawed because it’s

getting so loud that it may cause ear cancer. But that’s in my pessimistic

moments, when I feel that. Otherwise, the standards have risen immensely!

Regarding instrumental playing, which is what I was just speaking about in

the class, most of today’s youngsters are far better equipped than the exceptional

ones in the past. And the orchestras, in spite of the economic problems,

are still producing music on the highest level and increasingly higher level.

And there are increasing numbers of people listening to music, so therefore

I’m as cheerful about the times when I won’t be around as I can be, for the

sake of my children.

János Starker: To glories,

further glories. Of course, when anybody asks me this question, there

are always two ways I answer it. One of my writings deals with the

fact that in the twenty-first century, music may be outlawed because it’s

getting so loud that it may cause ear cancer. But that’s in my pessimistic

moments, when I feel that. Otherwise, the standards have risen immensely!

Regarding instrumental playing, which is what I was just speaking about in

the class, most of today’s youngsters are far better equipped than the exceptional

ones in the past. And the orchestras, in spite of the economic problems,

are still producing music on the highest level and increasingly higher level.

And there are increasing numbers of people listening to music, so therefore

I’m as cheerful about the times when I won’t be around as I can be, for the

sake of my children. BD: Do these musical laws and regulations change

as time goes on?

BD: Do these musical laws and regulations change

as time goes on? JS:

For many, many years in my life, all I was interested in was to try

to produce the highest under any circumstances, and I even stated at one

time that the audience is merely listening in. Eventually, as I grew

older, I found some fault with that, but it was based on the art for art’s

sake concept, which is still in me, somewhere. But the older I get,

the more and more I realize that I cannot expect the audience to look for

the same aspect of a musical composition. I spend a lifetime learning

it and condensing it and changing it and the whole evolutionary process.

The audience, especially with works that are not their daily diet, I have

to be careful to make sure that I present it in a way that it can be appreciated

even by those who have not heard the work before. It’s basically small

modifications, not a great deal of letting off of my artistic principles.

JS:

For many, many years in my life, all I was interested in was to try

to produce the highest under any circumstances, and I even stated at one

time that the audience is merely listening in. Eventually, as I grew

older, I found some fault with that, but it was based on the art for art’s

sake concept, which is still in me, somewhere. But the older I get,

the more and more I realize that I cannot expect the audience to look for

the same aspect of a musical composition. I spend a lifetime learning

it and condensing it and changing it and the whole evolutionary process.

The audience, especially with works that are not their daily diet, I have

to be careful to make sure that I present it in a way that it can be appreciated

even by those who have not heard the work before. It’s basically small

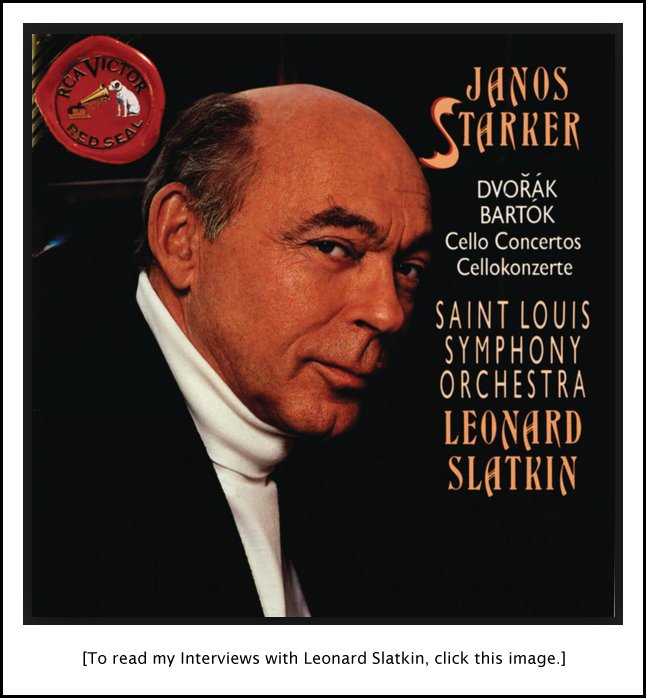

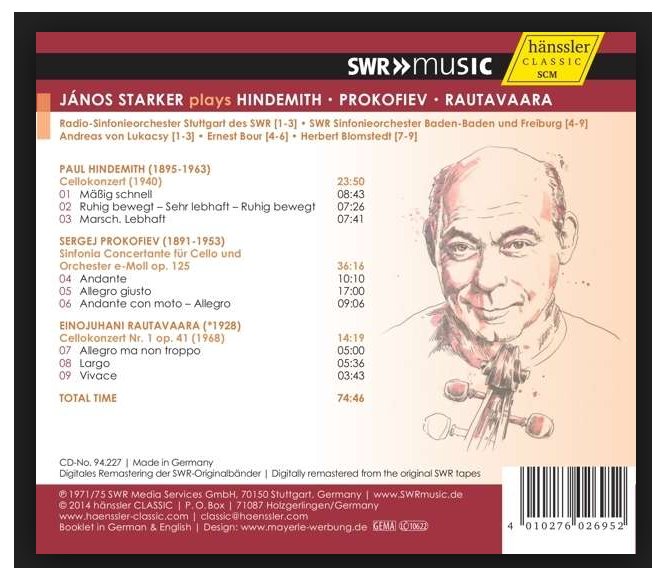

modifications, not a great deal of letting off of my artistic principles. JS: Most of the time I don’t choose the concertos.

There’s a list, something like forty-five different orchestral works from

which the conductor is supposed to choose according to his basic program

plan for that evening. Then we go back and forth. Here in Chicago

I was originally supposed to play, I think, the Saint-Saens Concerto because it’s a French program.

Since it’s too short, I proposed the Milhaud Concerto with it. Mr. Leinsdorf

said, “I’m not sure that I like that one, so how about something else?”

So then we considered a French baroque concerto, which was not enough interest

for the orchestra. So I said, “Why don’t we do the Bartók Concerto or the Hindemith Concerto?” and Leinsdorf replied, “Let’s

do Hindemith. It hasn’t been done and it’s such a marvelous piece!”

I consider it probably the best written and constructed cello concerto of

the twentieth century. [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Einojuhani Rautavaara

and Herbert Blomstedt.]

JS: Most of the time I don’t choose the concertos.

There’s a list, something like forty-five different orchestral works from

which the conductor is supposed to choose according to his basic program

plan for that evening. Then we go back and forth. Here in Chicago

I was originally supposed to play, I think, the Saint-Saens Concerto because it’s a French program.

Since it’s too short, I proposed the Milhaud Concerto with it. Mr. Leinsdorf

said, “I’m not sure that I like that one, so how about something else?”

So then we considered a French baroque concerto, which was not enough interest

for the orchestra. So I said, “Why don’t we do the Bartók Concerto or the Hindemith Concerto?” and Leinsdorf replied, “Let’s

do Hindemith. It hasn’t been done and it’s such a marvelous piece!”

I consider it probably the best written and constructed cello concerto of

the twentieth century. [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Einojuhani Rautavaara

and Herbert Blomstedt.] JS: If you’re speaking of the baroque ensembles

that are using these, my view has always been that I don’t like it if somebody

pretends to play baroque music according to the olden style, unless the

person goes back to the instruments that were used at the time, with the

same pitch, the same gut strings, without the end pin on the cello or the

gamba, and with the bows that were used. Another problem comes if it’s

presented in a modern kind of surrounding — such as Orchestra Hall

— with its large size which makes it nonsensical. If it’s

approximate, or as close as possible the original presentation of the music

with the instruments as they were at the time, then I find it very enlightening.

But would I want to spend a great deal of my time listening to it or making

it? I don’t play it because I don’t believe that I’m willing to do

that now — although I have a five string cello. But as long as it’s

presented maximally attempting to approximate the contemporary presentation

of those works, I find it very important, very enlightening, and sometimes

very enjoyable — if it’s done by players who are excellent.

JS: If you’re speaking of the baroque ensembles

that are using these, my view has always been that I don’t like it if somebody

pretends to play baroque music according to the olden style, unless the

person goes back to the instruments that were used at the time, with the

same pitch, the same gut strings, without the end pin on the cello or the

gamba, and with the bows that were used. Another problem comes if it’s

presented in a modern kind of surrounding — such as Orchestra Hall

— with its large size which makes it nonsensical. If it’s

approximate, or as close as possible the original presentation of the music

with the instruments as they were at the time, then I find it very enlightening.

But would I want to spend a great deal of my time listening to it or making

it? I don’t play it because I don’t believe that I’m willing to do

that now — although I have a five string cello. But as long as it’s

presented maximally attempting to approximate the contemporary presentation

of those works, I find it very important, very enlightening, and sometimes

very enjoyable — if it’s done by players who are excellent.

|

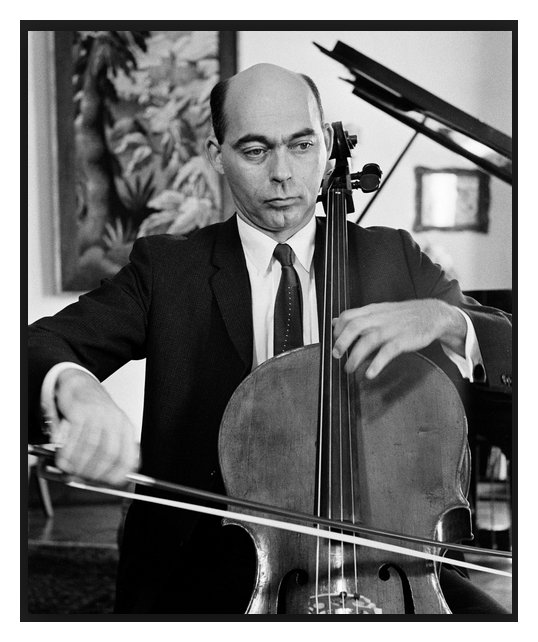

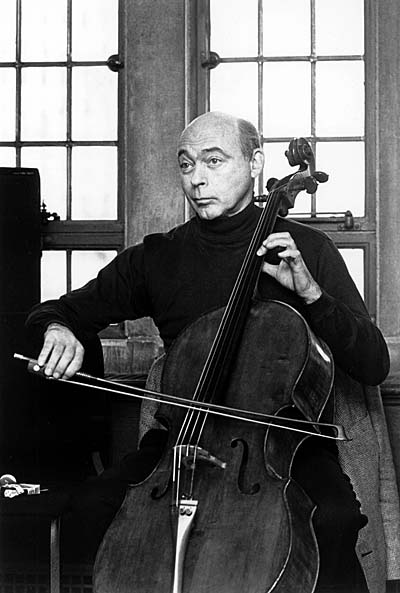

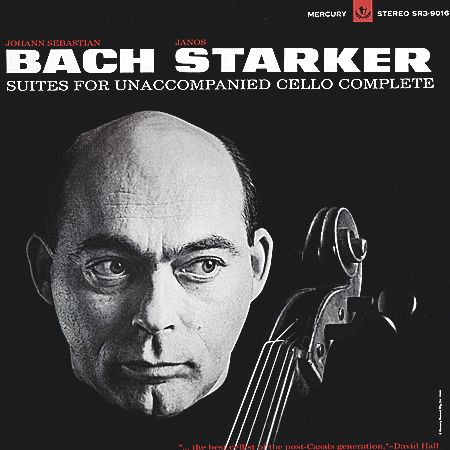

Of his many

honors, two distinguished awards stand as bookends on an extraordinarily

distinguished career of more than six decades: the 1948 Grand prix du

disque (France) and the 1997 Grammy Award (USA). Over the years János Starker has been the subject

of hundreds of major news stories, magazine articles and television documentaries

that emphasize his peerless technical mastery, intensely expressive playing,

and great communicative power. His performances are broadcast on radio and

television everywhere he goes. He has given world premiere performances

of concertos by American composers and by composers who have chosen to work

in the United States including David Baker, Antal Doráti, Bernard Heiden, Alan Hovhaness, Jean Martinon,

Miklós Rózsa,

Robert Starer, and Chou

Wen-chung, as well as world and American premieres of countless recital

works.

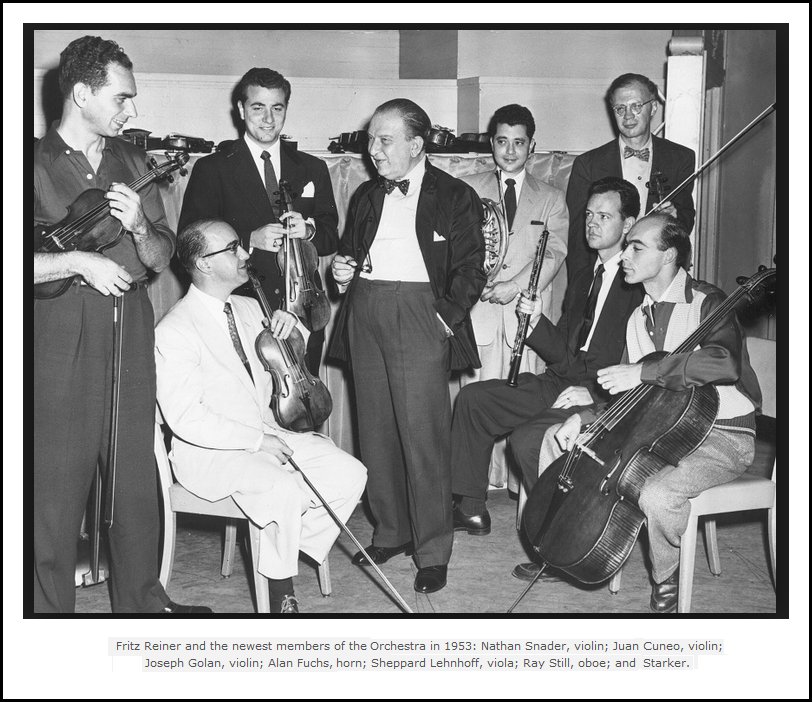

Starker continues to maintain a full teaching schedule at Indiana University (IU) in Bloomington, teaches many cello classes during his travels, and performs in recital halls and as a soloist with leading orchestras. Recent concert tours have taken him to Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, England, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Mexico, Portugal, Russia, Scotland, Spain, and Switzerland, as well as throughout the United States. János Starker has made Indiana University a mecca for the study of the cello. He joined the School of Music faculty in 1958. In 1962 he was awarded the title Distinguished Professor of Music. Starker has also taught with distinction at the Banff Centre in Alberta, Canada (17 years); the Hochschule für Musik in Essen, Germany (5 years). In 1970 Starker established two yearly student scholarships at IU to honor his former teachers. He founded the Eva Janzer Memorial Cello Center Foundation at IU in memory of the great cellist and much-loved teacher. The Foundation provides support for cello performance, teaching, and research, not only at Indiana University, but throughout the United States and the world. It also recognizes leading members of the world cello community through yearly awards, provides scholarships for outstanding cello students, and works closely with other organizations with similar purposes. János Starker is credited with numerous publications brought out by International Music, Peer International, Schirmer, and Occidental Press, and many of his articles have appeared in various magazines. Many of Starker's students are world-renowned soloists. They have won prestigious international cello competitions, are members of recognized chamber music ensembles, perform as principals or members of the cello sections in leading American and international orchestras, and have important and administrative and teaching positions in schools and institutions of higher education throughout the world. Born in Budapest,

Hungary, and educated there, János Starker survived detention

in a World War II Nazi work camp. Invited by Antal Doráti to become

first cellist of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, in 1948 Starker laid aside

his solo career and emigrated to the United States. He moved, with the great

Fritz Reiner, first to the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and then to the

Chicago Symphony. In 1954 Starker became an American citizen. Starker resumed

his career as a touring soloist in 1958, the same year he joined the faculty

of Indiana University. -- From the Indiana University

Website == == ==

== == == ==

To read my Interview with Richard Wernick, click HERE. To read my Interview with Richard Wilson, click HERE. |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on November 24, 1987.

Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1989, 1994 and 1999;

and on WNUR in 2004. The transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2009. More photos and links were added in 2015, and subsequently.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.