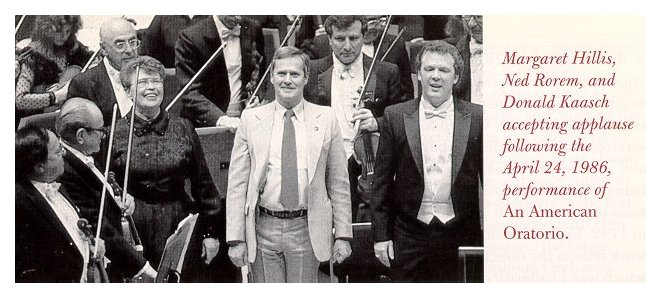

MH: Well, there

are some. There’s one that I did this past season by Ned Rorem that

I think is a very strong work called American

Oratorio. [See my Interview with Ned Rorem.]

It’s based on texts of American poets and there’s some prose from Mark Twain

in it. That’s an extraordinary work. I usually end up doing the

world premieres or contemporary pieces that balance the season. A couple

of years ago I did a world premiere of a piece by Ezra Lederman called A Mass for Cain, which is a very imposing

work. I sort of keep my feelers out among the best of the composers.

There’s a work that I can’t mention right now because I don’t know whether

it’s going to be programmed or not, but if Solti doesn’t want to do it, I

going to ask him if I can do it. That’s sort of the way it works.

Things will come across my desk. I get stacks and stacks of hopeful

works and I go through them very carefully and narrow them down to the strongest

pieces. Then I make my recommendations to Solti. The idea is if

he wants to do it, fine; if he doesn’t, then I’ll do it. [See my Interviews with Sir Georg Solti.]

MH: Well, there

are some. There’s one that I did this past season by Ned Rorem that

I think is a very strong work called American

Oratorio. [See my Interview with Ned Rorem.]

It’s based on texts of American poets and there’s some prose from Mark Twain

in it. That’s an extraordinary work. I usually end up doing the

world premieres or contemporary pieces that balance the season. A couple

of years ago I did a world premiere of a piece by Ezra Lederman called A Mass for Cain, which is a very imposing

work. I sort of keep my feelers out among the best of the composers.

There’s a work that I can’t mention right now because I don’t know whether

it’s going to be programmed or not, but if Solti doesn’t want to do it, I

going to ask him if I can do it. That’s sort of the way it works.

Things will come across my desk. I get stacks and stacks of hopeful

works and I go through them very carefully and narrow them down to the strongest

pieces. Then I make my recommendations to Solti. The idea is if

he wants to do it, fine; if he doesn’t, then I’ll do it. [See my Interviews with Sir Georg Solti.] BD: I have asked if there is a difference between

preparing something with soloists and without. What about an a cappella work as opposed to something

that is accompanied?

BD: I have asked if there is a difference between

preparing something with soloists and without. What about an a cappella work as opposed to something

that is accompanied?  MH: Maybe yes, maybe no. It depends upon

what work you are doing. Just last week we did the Fauré Requiem which was programmed along with

the Haydn Nelson Mass. The

Fauré is a very ethereal kind of work, but it does have moments of

very great drama. You have to keep the ethereal quality, and when the

drama comes in it has to have its punch. Now you think of Beethoven

and his relation to God, he was always fighting to get up there on that same

level with God. With Haydn, he was very happy. God was his best

friend, but there are moments of very great drama in that Mass, and you don’t have stage props to

show it. You don’t really have a story line to show it except “et mortuos,”

“be fearful of death.” That has to show in the color. You don’t

get any help from stage props, so to get the drama across on the concert

stage it takes much more intensity of projection. Whether it’s pianissimo or fortissimo, on the opera stage you do

have the action, you do have the story, you have the scenery. But it’s

not easy there either; it’s very difficult. Opera is, in a way, another

musical world. My favorite piece happens to be the Verdi Otello, and all of that joy in the opening

is translated to terror and awful things at the end, and it’s all spoken so

beautifully in the music. Musically it has such an integrity that you

hardly need the stage, but when you add the stage the piece really reaches

its culmination. But the musical problems are the same, the dramatic

problems like in a Missa Solemnis

are the same. It’s just that opera is harder because you have to memorize

it. The Symphony Chorus here learned Moses and Aron about twelve or fourteen

years ago. They learned it in six weeks, which should go in the Guinness

Book of Records, but they didn’t have to roll around in the blood right on

the stage. They didn’t have to memorize it. Opera is very, very

difficult.

MH: Maybe yes, maybe no. It depends upon

what work you are doing. Just last week we did the Fauré Requiem which was programmed along with

the Haydn Nelson Mass. The

Fauré is a very ethereal kind of work, but it does have moments of

very great drama. You have to keep the ethereal quality, and when the

drama comes in it has to have its punch. Now you think of Beethoven

and his relation to God, he was always fighting to get up there on that same

level with God. With Haydn, he was very happy. God was his best

friend, but there are moments of very great drama in that Mass, and you don’t have stage props to

show it. You don’t really have a story line to show it except “et mortuos,”

“be fearful of death.” That has to show in the color. You don’t

get any help from stage props, so to get the drama across on the concert

stage it takes much more intensity of projection. Whether it’s pianissimo or fortissimo, on the opera stage you do

have the action, you do have the story, you have the scenery. But it’s

not easy there either; it’s very difficult. Opera is, in a way, another

musical world. My favorite piece happens to be the Verdi Otello, and all of that joy in the opening

is translated to terror and awful things at the end, and it’s all spoken so

beautifully in the music. Musically it has such an integrity that you

hardly need the stage, but when you add the stage the piece really reaches

its culmination. But the musical problems are the same, the dramatic

problems like in a Missa Solemnis

are the same. It’s just that opera is harder because you have to memorize

it. The Symphony Chorus here learned Moses and Aron about twelve or fourteen

years ago. They learned it in six weeks, which should go in the Guinness

Book of Records, but they didn’t have to roll around in the blood right on

the stage. They didn’t have to memorize it. Opera is very, very

difficult.  MH: I wish there

were more and I wish that each individual place paid more. In the Symphony

Chorus I have several singers who are wonderful, but they have no ambitions

at all at being soloists. Their life’s ambition is to be able to earn

a dignified living singing in a chorus. At this point there’s been a

great change. I would say right now the choruses are about where orchestras

were fifty years ago when there were amateur orchestras all over the place.

There will always be amateur choruses and there should be, but there may be

now about forty-five professional choruses, of which only three afford a

real living. It’s difficult to get the public to see the difference

between the amateur chorus and the professional chorus, very difficult.

Once they hear them side by side they know the difference, but the pros really

deserve more recognition just in terms of the money. At this point it

is so little that they earn that what it stands for, more than anything else,

is recognition and appreciation. I think that’s going to change and

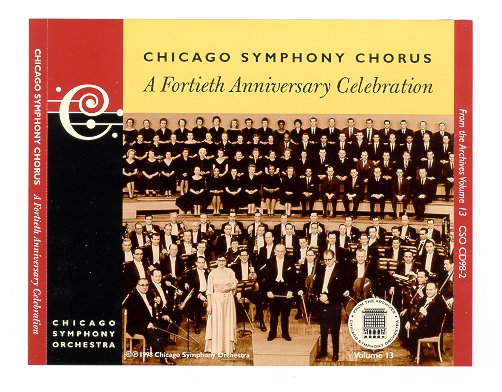

I think it is in the process of change right now. When I started the

Symphony Chorus (in 1957), it was totally amateur. [Photo at right (CD cover) taken in March, 1959,

with conductors Fritz Reiner (on podium) and Walter Hendl] There

was no professional standard when it came to vocal ensembles in Chicago

at that time. The problem was to instill in them some sense of responsibility

toward what they were doing. Just to be at rehearsals on time, it took

me two years to teach them that. And then there were certain basic skills

that they had to learn. They finally understood the importance of that

and did it finally on their own initiative instead of my screaming at them.

After three years as an amateur chorus, there were some singers who were

really good enough to be recognized as professional, so I said to the management,

“It’s time. We have a few.” And gradually it’s grown up to a

hundred five out of a hundred eighty in the chorus. The rest we do

not call amateurs because they’re not; they’re volunteers. All but

about six people in the chorus have at least a Bachelor’s degree in music.

Many of them have Masters and a few have Doctorates. And they work

very hard. They all study, every one of them. Now the volunteers

are as good as the pros except most of them don’t have the instrument in

the throat. They don’t have the Stradivarius in the throat, but they

are musical, they are intelligent, they read very well, and in a way they

are the backbone of the chorus.

MH: I wish there

were more and I wish that each individual place paid more. In the Symphony

Chorus I have several singers who are wonderful, but they have no ambitions

at all at being soloists. Their life’s ambition is to be able to earn

a dignified living singing in a chorus. At this point there’s been a

great change. I would say right now the choruses are about where orchestras

were fifty years ago when there were amateur orchestras all over the place.

There will always be amateur choruses and there should be, but there may be

now about forty-five professional choruses, of which only three afford a

real living. It’s difficult to get the public to see the difference

between the amateur chorus and the professional chorus, very difficult.

Once they hear them side by side they know the difference, but the pros really

deserve more recognition just in terms of the money. At this point it

is so little that they earn that what it stands for, more than anything else,

is recognition and appreciation. I think that’s going to change and

I think it is in the process of change right now. When I started the

Symphony Chorus (in 1957), it was totally amateur. [Photo at right (CD cover) taken in March, 1959,

with conductors Fritz Reiner (on podium) and Walter Hendl] There

was no professional standard when it came to vocal ensembles in Chicago

at that time. The problem was to instill in them some sense of responsibility

toward what they were doing. Just to be at rehearsals on time, it took

me two years to teach them that. And then there were certain basic skills

that they had to learn. They finally understood the importance of that

and did it finally on their own initiative instead of my screaming at them.

After three years as an amateur chorus, there were some singers who were

really good enough to be recognized as professional, so I said to the management,

“It’s time. We have a few.” And gradually it’s grown up to a

hundred five out of a hundred eighty in the chorus. The rest we do

not call amateurs because they’re not; they’re volunteers. All but

about six people in the chorus have at least a Bachelor’s degree in music.

Many of them have Masters and a few have Doctorates. And they work

very hard. They all study, every one of them. Now the volunteers

are as good as the pros except most of them don’t have the instrument in

the throat. They don’t have the Stradivarius in the throat, but they

are musical, they are intelligent, they read very well, and in a way they

are the backbone of the chorus.  BD: Is there too much hype in music now?

BD: Is there too much hype in music now? |

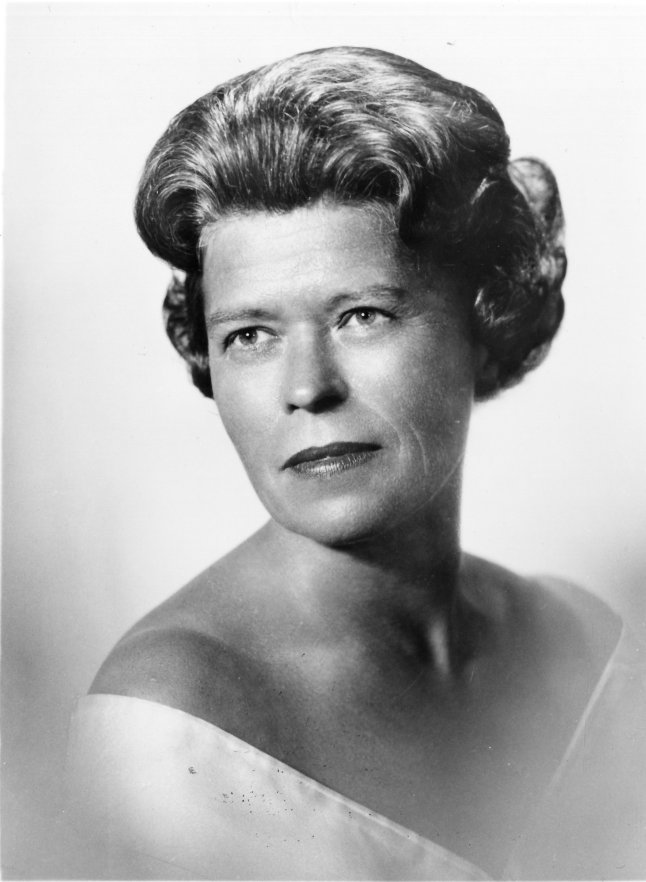

Margaret Hillis, 76, Conductor

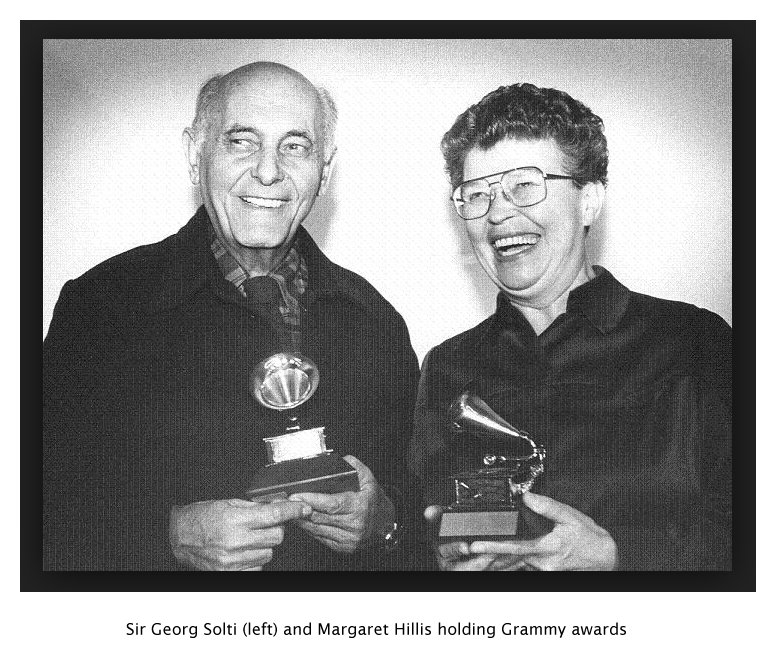

Led Chicago Symphony Chorus By ALLAN KOZINN Published: February 6, 1998 in The New York Times Margaret Hillis, who founded the Chicago Symphony Chorus and was the first woman to conduct the Chicago Symphony itself, died yesterday at Evanston Hospital, in Evanston, Ill. She was 76, and lived in Wilmette, Ill. The cause was lung cancer, said Synneve Carlino, a spokeswoman for the Chicago Symphony. Ms. Hillis, who appeared as a guest conductor with many American orchestras, including the National Symphony, the St. Louis Symphony, the Oregon Symphony and the Minnesota Orchestra, often said that orchestral conducting was her first love. She established herself as a choral conductor, however, because there were virtually no orchestral conducting opportunities for women when she began her career in the 1950's. ''I learned to take a strong disadvantage and turn it to my advantage,'' she once said, and indeed, her work with the Chicago Symphony Chorus, as well as the choruses of the San Francisco Symphony and the Cleveland Orchestra, brought her considerable renown. It also helped smooth her path to orchestral podiums. In 1957, when she started her chorus in Chicago, she made her conducting debut with the Chicago Symphony. She led the orchestra several times thereafter, both in Chicago and on tour In 1977, she had a notable appearance as a last-minute substitute for Sir Georg Solti, who had fallen ill, in a performance of Mahler's Eighth Symphony at Carnegie Hall. Ms. Hillis was born in Kokomo, Ind., in 1921. She began studying the piano when she was 5, but said that by the time she was 8 she began dreaming of becoming a conductor. She studied music at Indiana University in Bloomington, but suspended her studies during World War II to become a civilian flight instructor in Muncie, Ind. After she completed her bachelor's degree in 1947, Ms. Hillis moved to New York, where she studied choral conducting with Robert Shaw at the Juilliard School. She soon became Mr. Shaw's assistant at the Collegiate Chorale, and in 1950 she founded the Tanglewood Alumni Chorus, which later performed as the New York Concert Choir and Orchestra. In the 1950's she also worked as a choral conductor for the New York City Opera and the American Opera Society. During her years in New York she taught choral conducting at the Juilliard School and Union Theological Seminary, and she formed the American Choral Foundation, an organization that sought to raise the standards of choral performance. The conductor Fritz Reiner invited her to start a chorus for the Chicago Symphony in 1957, and within a decade she had established one of the finest professional choirs in the country. She also began working with community and regional orchestras, and was director for several years of the Kenosha Civic Orchestra, the Chicago Civic Orchestra and the Elgin Symphony. Starting in the late 1970's, she worked more actively as a guest conductor. Although the directors of orchestral choirs do most of their work behind the scenes, rehearsing their choruses for performances conducted by the orchestra's music director or a guest conductor, Ms. Hillis's work with the Chicago Symphony Chorus was widely praised. She received Grammy awards for nine recordings for which she prepared the chorus for Mr. Solti, among them a Verdi Requiem, Beethoven's Missa Solemnis, two recordings of the Brahms German Requiem, Haydn's 'Creation' and Bach's Mass in B minor. Ms. Hillis is survived by three brothers: Elwood Hillis, a former Congressman, of Culver, Ind; Robert Hillis of Kokomo, and Joseph Hillis of Lafayette, Calif. She had a sense of humor about her struggle for recognition in a profession dominated by men. ''There's only one woman I know who could never be a symphony conductor,'' she told The New York Times in 1979, ''and that's the Venus de Milo.'' |

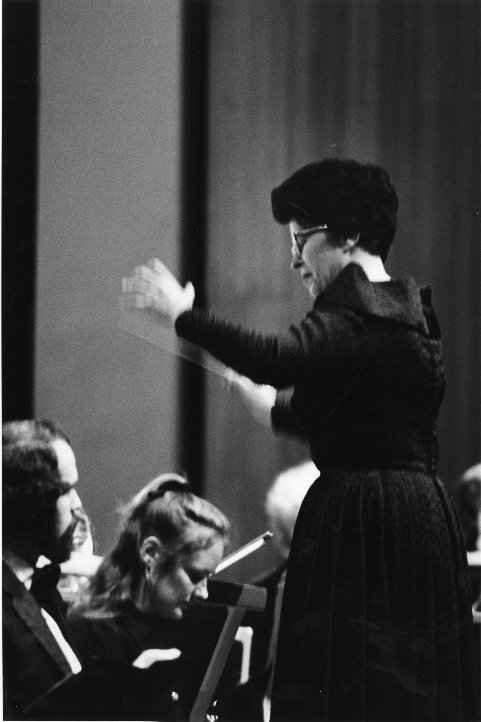

This interview was recorded at the suburban Chicago home of Margaret

Hillis on July 29, 1986. Portions (along with recordings) were used

on WNIB later that year, and again several times thereafter. This transcription

was made and posted on this website in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.