BD: How are the Verdi roles different

from the French ones, or those of Puccini — if

at all?

BD: How are the Verdi roles different

from the French ones, or those of Puccini — if

at all? SM: That’s just as damaging because I can just do

his traffic patterns and my own character projection. Some directors

will only give you overall ideas and expect you to bring something to

flesh it out. Those guys are okay. Then there are a few

who simply don’t know, and don’t know that they don’t know, and they throw

out some of the ‘gawd-awfulest’ ideas. Often, to try and make

intimate scenes, they will have characters singing to each other. On

the surface that sounds like a good idea, but constant profile with the

voice going into the wings does not work. There’s an odd thing

that happens, and the audience doesn’t believe it. The enormous

public at the back of the house is almost a city block away, and that

makes the audience feel left out if they don’t see more of your full frontal

face. They also don’t hear you as well. But you can’t go

to the other extreme and never face your lover in a scene. There

are lots of ways of playing it without always singing to the wings.

You can position yourself so that important or passionate lines can

be sung to the person, but in an open position.

SM: That’s just as damaging because I can just do

his traffic patterns and my own character projection. Some directors

will only give you overall ideas and expect you to bring something to

flesh it out. Those guys are okay. Then there are a few

who simply don’t know, and don’t know that they don’t know, and they throw

out some of the ‘gawd-awfulest’ ideas. Often, to try and make

intimate scenes, they will have characters singing to each other. On

the surface that sounds like a good idea, but constant profile with the

voice going into the wings does not work. There’s an odd thing

that happens, and the audience doesn’t believe it. The enormous

public at the back of the house is almost a city block away, and that

makes the audience feel left out if they don’t see more of your full frontal

face. They also don’t hear you as well. But you can’t go

to the other extreme and never face your lover in a scene. There

are lots of ways of playing it without always singing to the wings.

You can position yourself so that important or passionate lines can

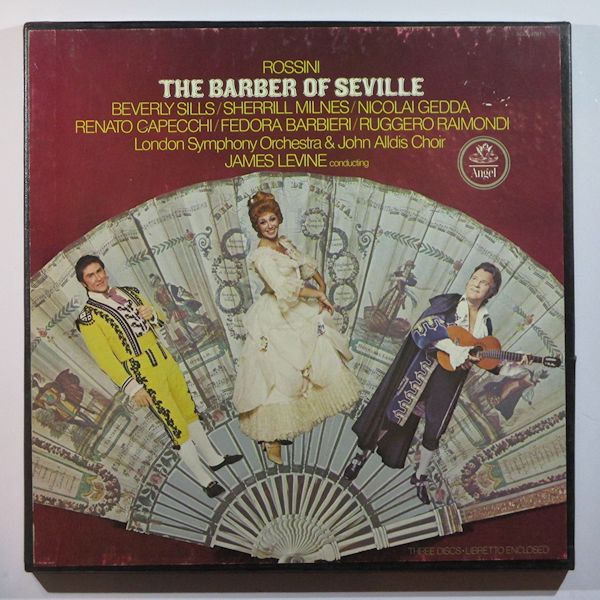

be sung to the person, but in an open position.  SM: Not really. I’ve played The Barber

of Seville many, many, many times, but I’m getting a little

old for Figaro. I’m kind of serious and evil, so I like playing

those kinds of parts! [Laughs] Evil is kind of fun, and

my good guys are all serious. The closest thing to screwing around

is Iago in the first act where he’s egging on the people at the party.

It’s all a put-on because, except for the Credo, Iago doesn’t

say an honest word in the whole opera... and maybe in his whole life.

Perhaps he is only honest when he’s by himself, and in the opera the

only time is the Credo.

SM: Not really. I’ve played The Barber

of Seville many, many, many times, but I’m getting a little

old for Figaro. I’m kind of serious and evil, so I like playing

those kinds of parts! [Laughs] Evil is kind of fun, and

my good guys are all serious. The closest thing to screwing around

is Iago in the first act where he’s egging on the people at the party.

It’s all a put-on because, except for the Credo, Iago doesn’t

say an honest word in the whole opera... and maybe in his whole life.

Perhaps he is only honest when he’s by himself, and in the opera the

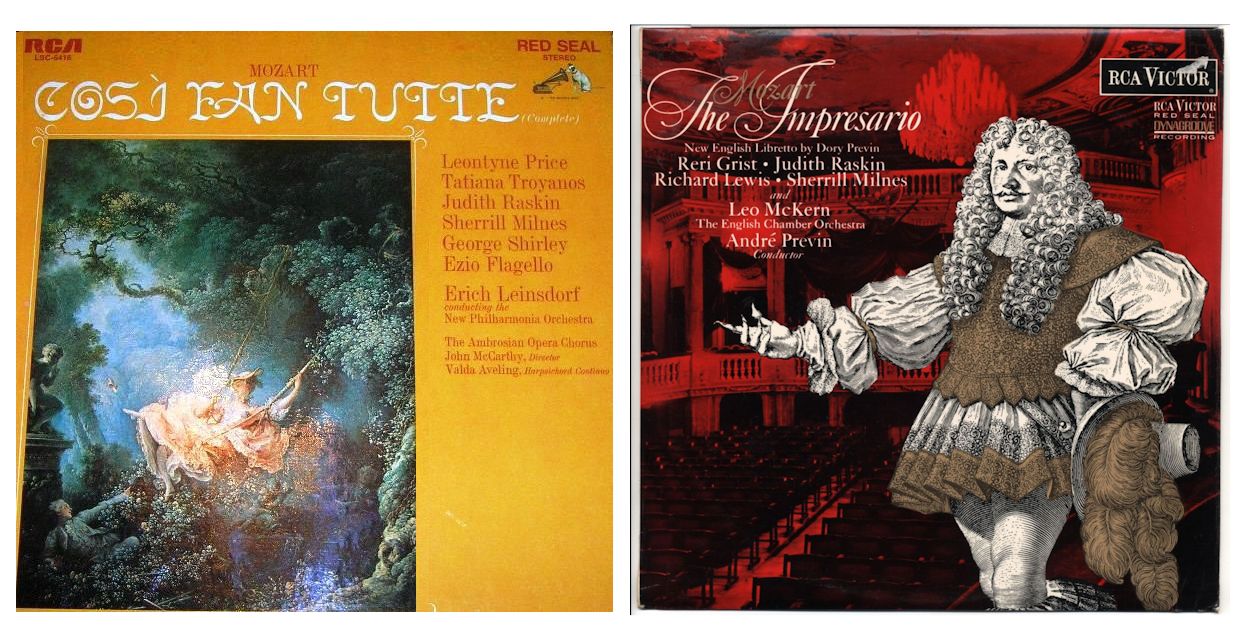

only time is the Credo. SM: Oh, I think so. There’s

a time and a place for it. All the things I did with Goldovsky

were in English. Probably ten of my often-used roles I knew

in English before I sang them in Italian, and I’m probably the better

performer of those roles because of it. If we never learned a

role without knowing the language, we’d probably never learn anything

because the time-factor would be so enormous. When you have sung

it in English, you are singing the lines and making the stage movements

knowing each word, and it makes you more believable as an actor.

So it does a service for the performer as well as for the audience.

It’s a give and take, of course. You lose a certain flavor that

the composer was intending. This is not just opera in English, but

also Italian opera in German, or German opera in French. [Sneers]

Ugh! But it’s only ‘ugh’ if you are used to hearing it in

another language. For me, there has to be a certain progression.

I would know a part only in English, then better in English than Italian,

then about equally well — which is the most

difficult because when starting a phrase, if I didn’t feed myself the

right word, I’d be in the other language and not be able to get out of

it. Now, I suppose I know all these roles better in Italian, but

operas vary in their adaptability. Comedies are better, and operas

in translation are often better for first-time listeners.

SM: Oh, I think so. There’s

a time and a place for it. All the things I did with Goldovsky

were in English. Probably ten of my often-used roles I knew

in English before I sang them in Italian, and I’m probably the better

performer of those roles because of it. If we never learned a

role without knowing the language, we’d probably never learn anything

because the time-factor would be so enormous. When you have sung

it in English, you are singing the lines and making the stage movements

knowing each word, and it makes you more believable as an actor.

So it does a service for the performer as well as for the audience.

It’s a give and take, of course. You lose a certain flavor that

the composer was intending. This is not just opera in English, but

also Italian opera in German, or German opera in French. [Sneers]

Ugh! But it’s only ‘ugh’ if you are used to hearing it in

another language. For me, there has to be a certain progression.

I would know a part only in English, then better in English than Italian,

then about equally well — which is the most

difficult because when starting a phrase, if I didn’t feed myself the

right word, I’d be in the other language and not be able to get out of

it. Now, I suppose I know all these roles better in Italian, but

operas vary in their adaptability. Comedies are better, and operas

in translation are often better for first-time listeners.

BD: Is Hamlet a Dane, or a Shakespearean, or a French

soul?

BD: Is Hamlet a Dane, or a Shakespearean, or a French

soul? BD: As a baritone, sometimes you kill

and sometimes you are killed. Which would you rather?

BD: As a baritone, sometimes you kill

and sometimes you are killed. Which would you rather? SM: Sure, but it’s more

than three hours. That’s just walking out on stage. The

day of a performance is pretty much given to the performance, and what

you need for that. But on non-performance days, we conduct more

normal lives, with business pursuits in other areas.

SM: Sure, but it’s more

than three hours. That’s just walking out on stage. The

day of a performance is pretty much given to the performance, and what

you need for that. But on non-performance days, we conduct more

normal lives, with business pursuits in other areas. BD: Your voice range dictated a

lot of what you would sing. How else did you decide which

roles you would accept and which roles you would not accept?

BD: Your voice range dictated a

lot of what you would sing. How else did you decide which

roles you would accept and which roles you would not accept?

BD: Is he too much of an idealist?

BD: Is he too much of an idealist?

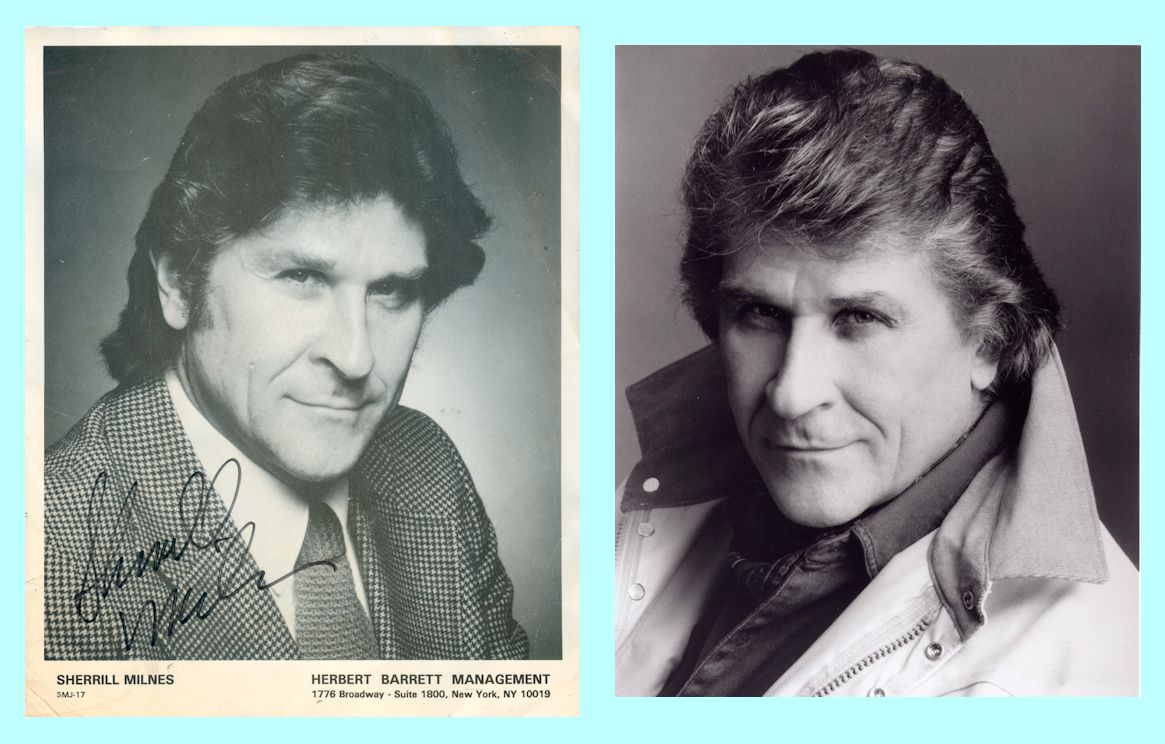

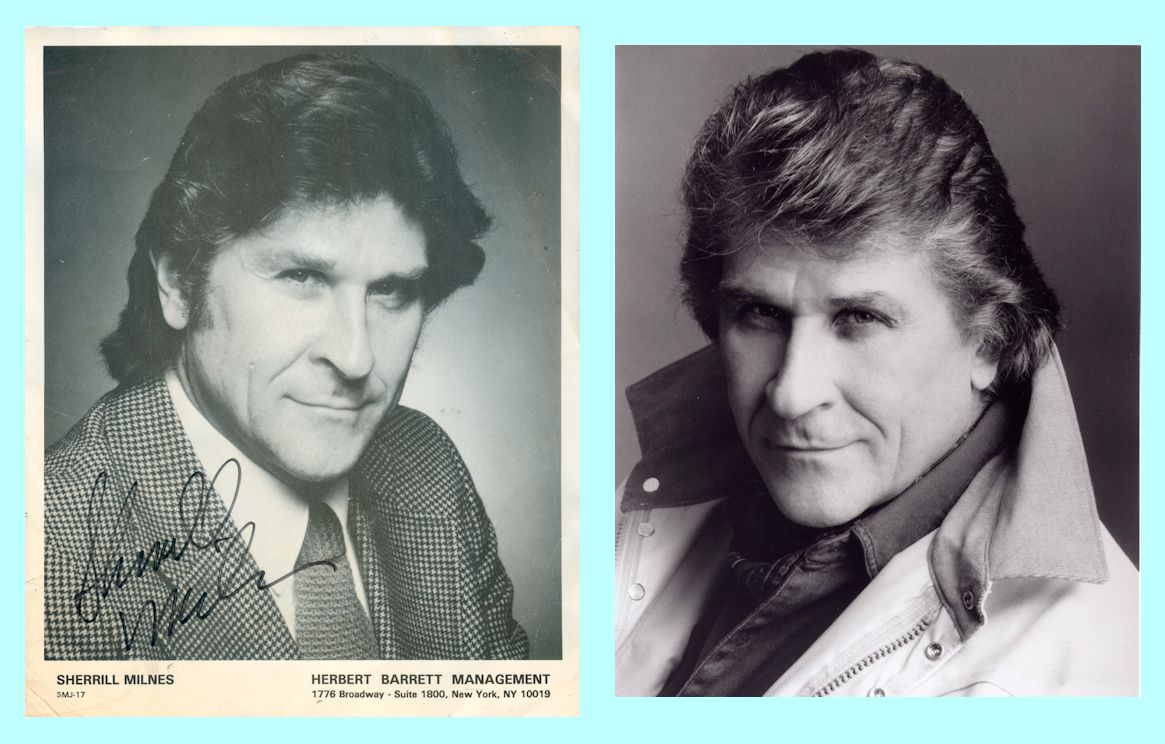

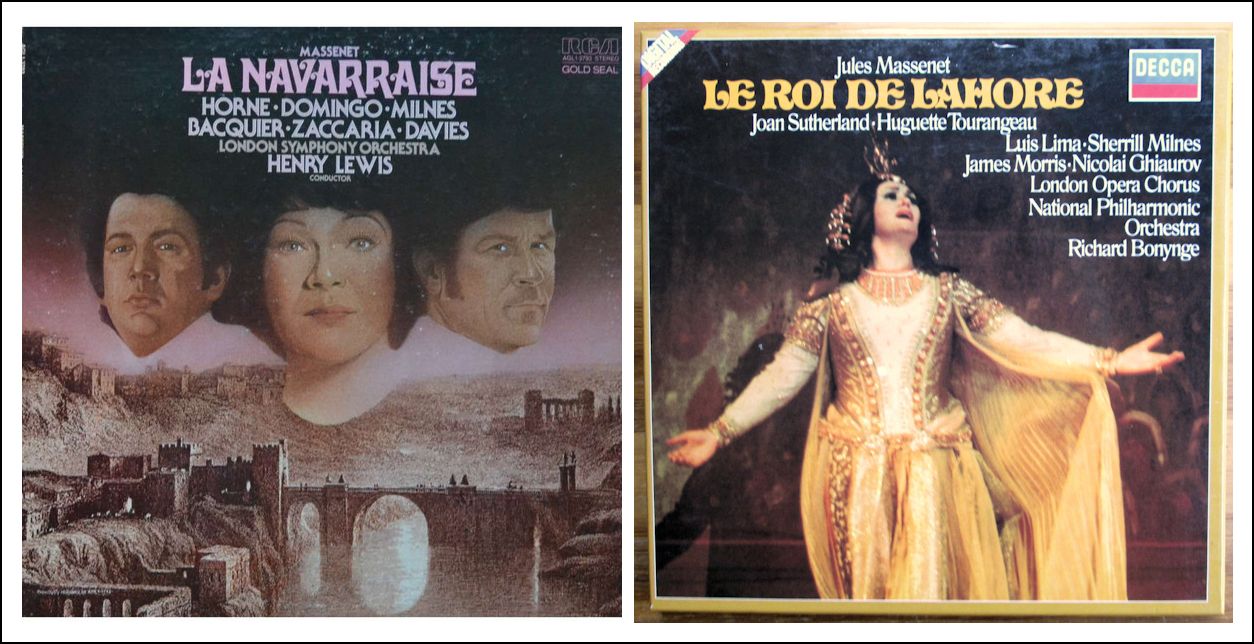

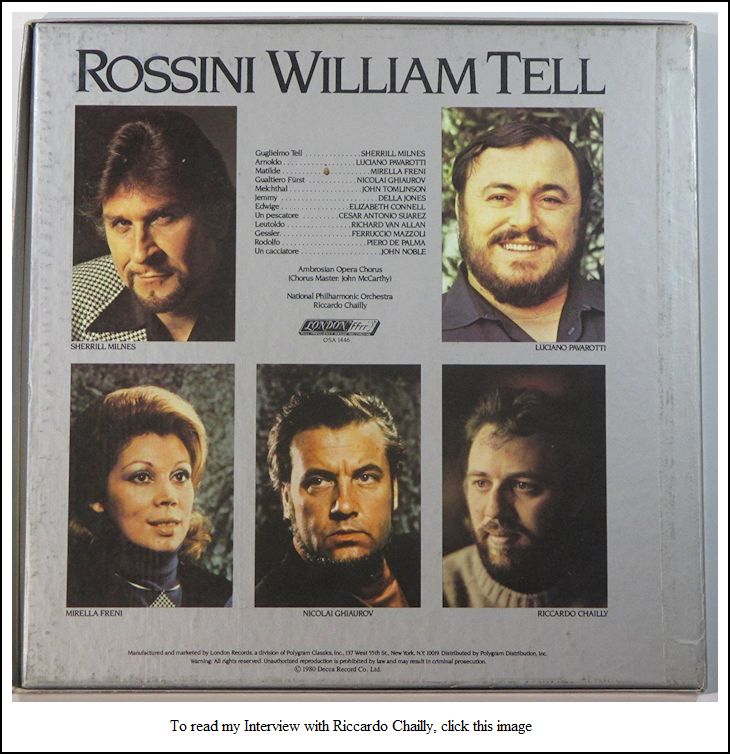

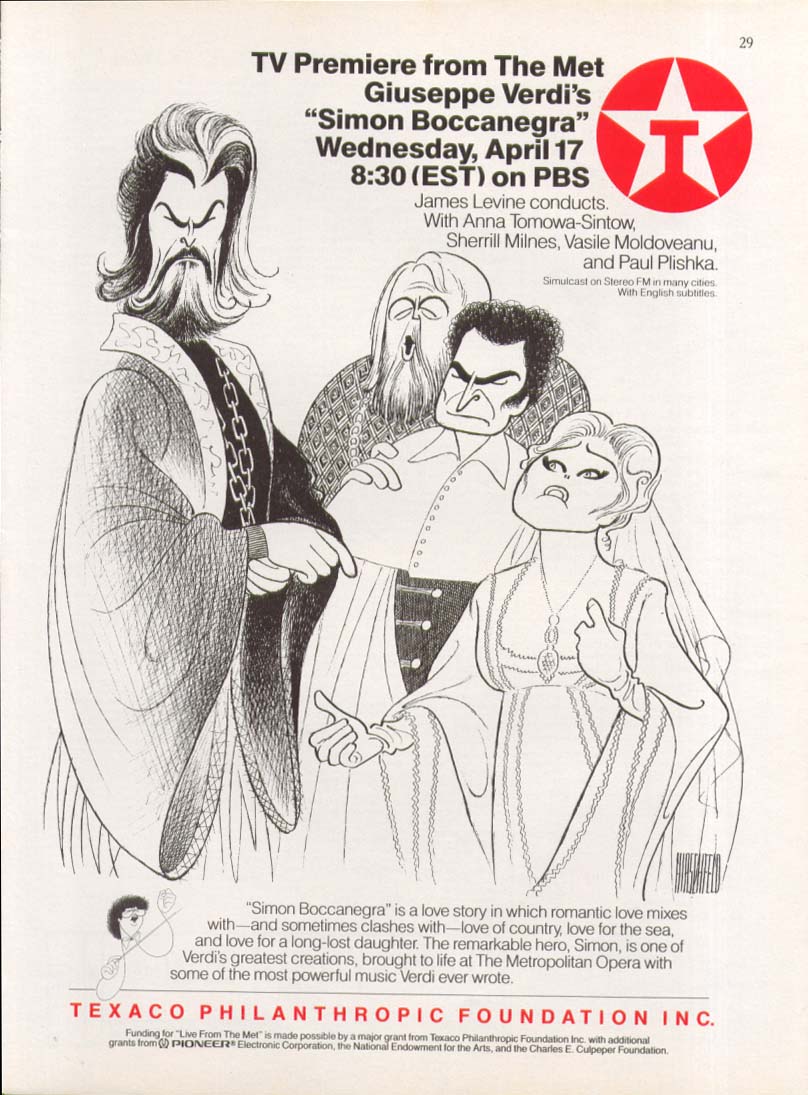

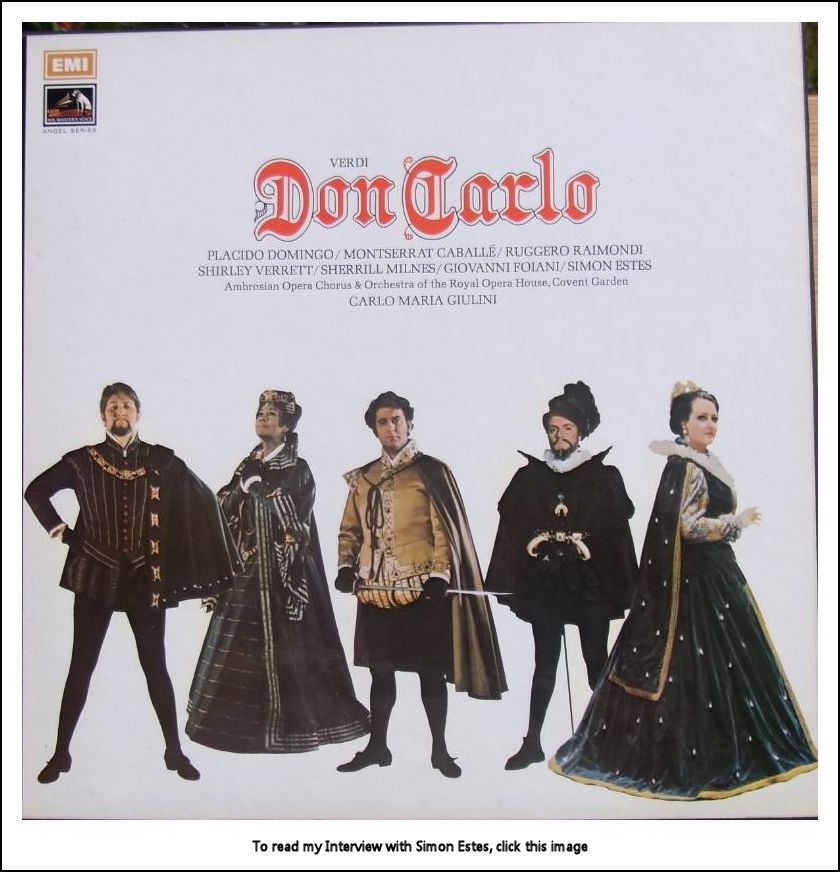

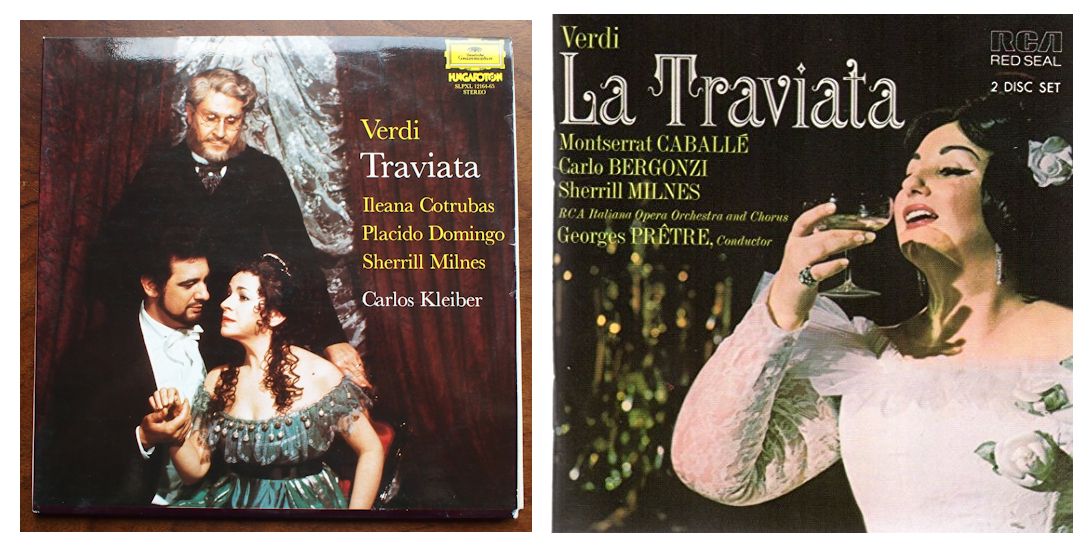

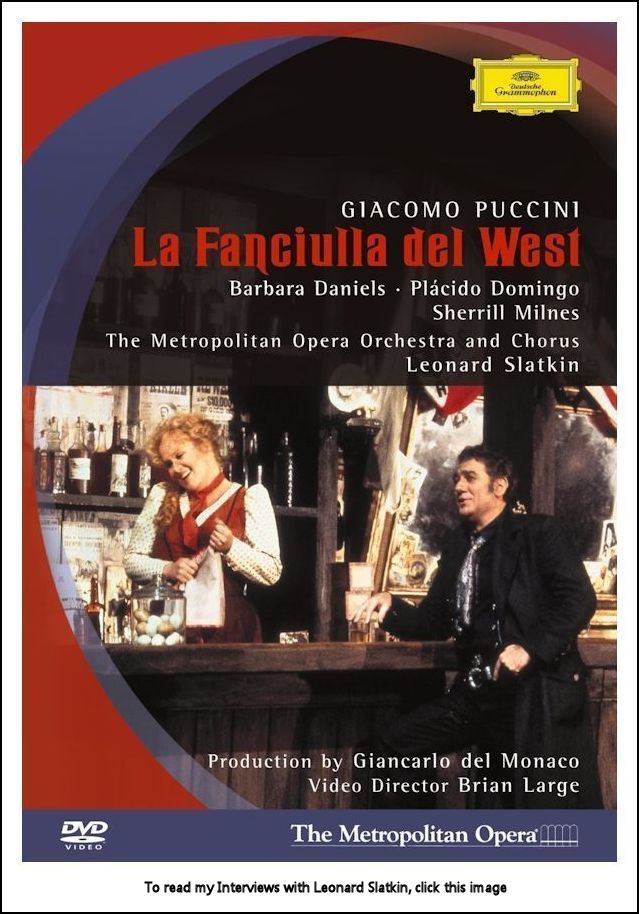

Sherrill Milnes at Lyric

Opera of Chicago

1971 - Don Carlo (Rodrigo) with Cossutta, Lorengar, Cossotto, Ghiaurov, Sotin; Bartoletti, Mansouri 1972 - Ballo in Maschera (Renato) with Arroyo, Tagliavini, Koszut, Baldani, Ferrin, Voketaitis; Dohnányi, Gobbi 1979 - Simon Boccanegra (Simon) with Shade, Cossutta, Morris, Stone, Toliver; Bartoletti, Frisell, Schuler (lights)

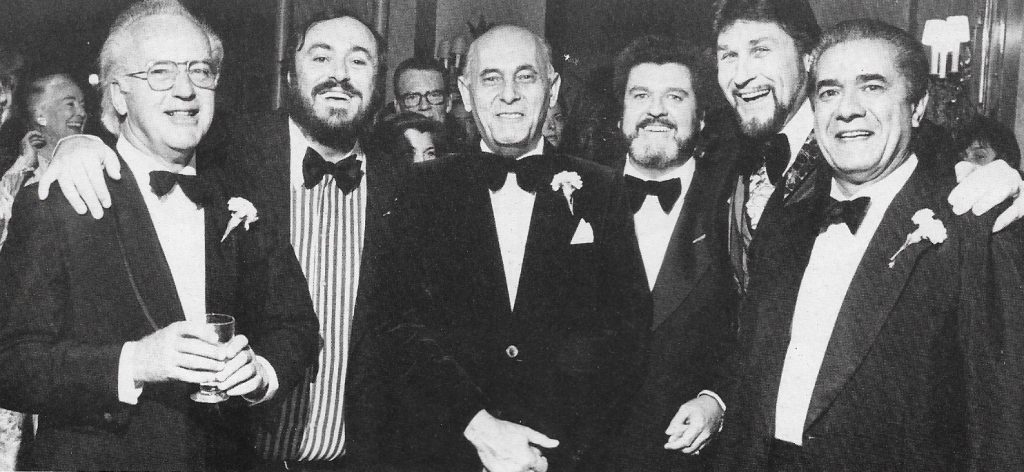

Léopold Simoneau, Luciano Pavarotti, Sir Georg Solti, Carlo Cossutta, Sherrill Milnes, and Giuseppe di Stefano (l-r) at the Lyric Opera of Chicago 25th Anniversary Gala, October 14, 1979. [Among the many others who participated were Jon Vickers, Alfredo Kraus, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bidú Sayāo, Eleanor Steber, Giulietta Simionato, Judith Blegen, Richard Stilwell, Kathleen Kuhlmann, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Maria Tallchief. The emcee was Sam Wanamaker.] 1985-86 [Opening Night] - Otello (Iago) with Domingo/Johns, M. Price, McCauley, Redmon, Plishka; Bartoletti, Diaz 1987-88 - Tosca (Scarpia) with Scotto, Ciannella, Patterson, Tajo, Andreolli; Tilson Thomas, Gobbi (orig prod)/Kellner 1989-90 - Hamlet (Hamlet) with Welting, Kunde, Palmer; Rudel, Melano |

BD: You can just raise an eyebrow,

and it reads on the screen.

BD: You can just raise an eyebrow,

and it reads on the screen. BD: They walk off into the sunset!

BD: They walk off into the sunset! BD: [Pretending to be cynical] But

she’s dead and there’s nothing more he can do for her.

BD: [Pretending to be cynical] But

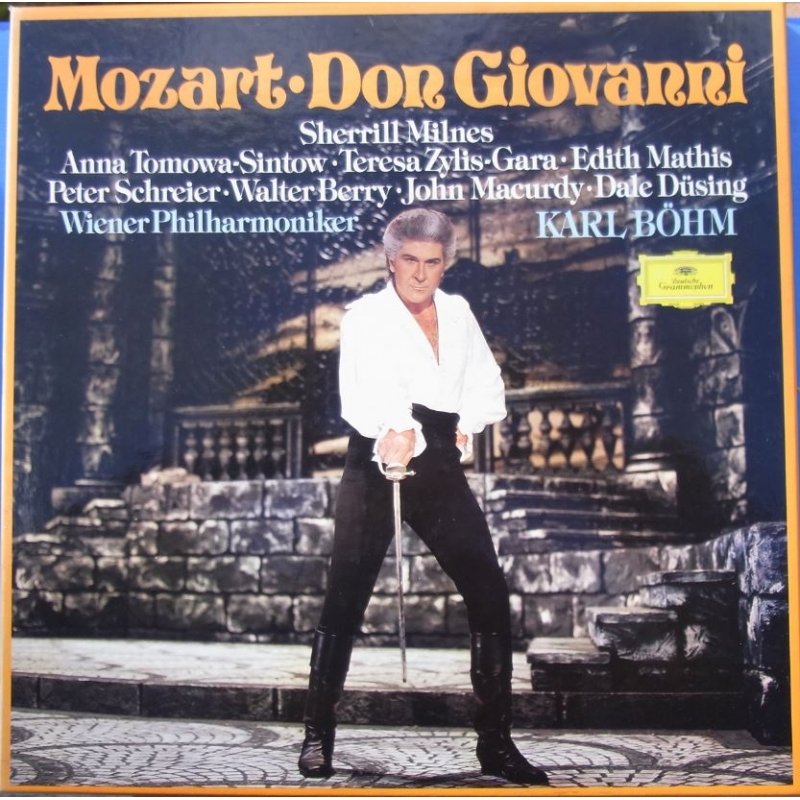

she’s dead and there’s nothing more he can do for her. SM: Right. It should be a given. But

this is a hurry-up mentality, and everybody’s in on it. We don’t

give pieces enough time. For Giovanni in Italian I spent a

year. For Falstaff I spent a year. I had sung Giovanni

in English, nevertheless, my first Giovanni in Italian was at the Met,

which is not an undiscovered place to do it. So I worked very

hard. I remember speaking about it with Ruggero Raimondi, who is

actually a bit younger than I am, but as an Italian he didn’t do the role

in English. The first time he did it was in Italian, so his number

of performances was far greater than mine when I did my first one.

He probably had already done thirty or forty, and I had done thirty or

forty, but in English. He said to me that recitative-operas are tough.

The memory of recitatives is different than when there’s melody behind

it. He said that you have to have those recitatives so well in

your mouth and your mind that they’ll come out correctly if you fell

asleep! [Laughs] That means hundreds of repetitions.

You have to develop what is called ‘muscle memory’.

That is, you’ve done it so often that even if you can’t

remember what that next line is, the instant you sing it, your mouth makes

the right word. If you don’t have any muscle memory there’s no way

that everyone will remember every word of every part at the instant you

have to sing it.

SM: Right. It should be a given. But

this is a hurry-up mentality, and everybody’s in on it. We don’t

give pieces enough time. For Giovanni in Italian I spent a

year. For Falstaff I spent a year. I had sung Giovanni

in English, nevertheless, my first Giovanni in Italian was at the Met,

which is not an undiscovered place to do it. So I worked very

hard. I remember speaking about it with Ruggero Raimondi, who is

actually a bit younger than I am, but as an Italian he didn’t do the role

in English. The first time he did it was in Italian, so his number

of performances was far greater than mine when I did my first one.

He probably had already done thirty or forty, and I had done thirty or

forty, but in English. He said to me that recitative-operas are tough.

The memory of recitatives is different than when there’s melody behind

it. He said that you have to have those recitatives so well in

your mouth and your mind that they’ll come out correctly if you fell

asleep! [Laughs] That means hundreds of repetitions.

You have to develop what is called ‘muscle memory’.

That is, you’ve done it so often that even if you can’t

remember what that next line is, the instant you sing it, your mouth makes

the right word. If you don’t have any muscle memory there’s no way

that everyone will remember every word of every part at the instant you

have to sing it.

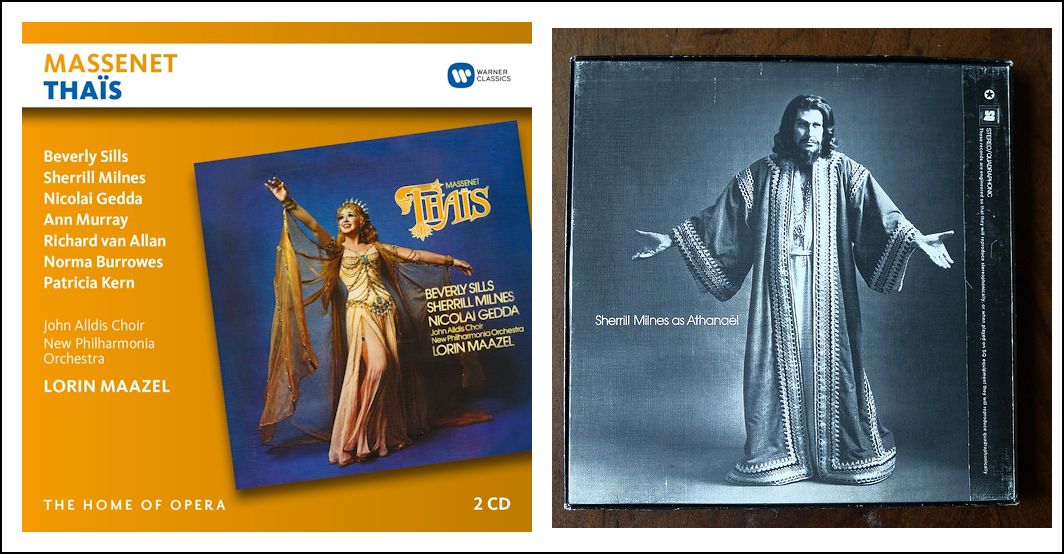

© 1985 & 1993 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on October 9, 1985, and February 9, 1993. Much of the first interview was published in the Massenet Newsletter in January, 1990. Portions of both interviews were broadcast on WNIB in 1986, 1988, 1990, and 1995. The transcription of the second interview was made in 2017, and both were posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.