SH: I’ve done some transcriptions, yes. In

fact, I have a record of encore pieces that I think is just due to be released

in the States; it’s been out in Europe for a little bit about a few months.

There are twenty different encores; some English composers, Quilter songs,

and four of them are my own transcriptions, including one of “My Favorite

Things” from The Sound of Music,

which is really going over that border line.

SH: I’ve done some transcriptions, yes. In

fact, I have a record of encore pieces that I think is just due to be released

in the States; it’s been out in Europe for a little bit about a few months.

There are twenty different encores; some English composers, Quilter songs,

and four of them are my own transcriptions, including one of “My Favorite

Things” from The Sound of Music,

which is really going over that border line.  SH: Sometimes they don’t work very well, but they

vary between Mozart and some of the contemporary composers. Personally,

I think the piano really did reach its peak as an instrument in the Romantic

era. The actual instrument was fully developed around the turn of the

century, and into the early decades of this century. So often, tonal

music sounds better on the piano than atonal music. I don’t think that’s

true for every form, but I think with a string quartet, for instance, I would

prefer to hear music of an atonal nature on a string quartet than I would

on the piano. I think it’s to do with harmonics; with the pedal, you

activate many harmonics on the instrument.

SH: Sometimes they don’t work very well, but they

vary between Mozart and some of the contemporary composers. Personally,

I think the piano really did reach its peak as an instrument in the Romantic

era. The actual instrument was fully developed around the turn of the

century, and into the early decades of this century. So often, tonal

music sounds better on the piano than atonal music. I don’t think that’s

true for every form, but I think with a string quartet, for instance, I would

prefer to hear music of an atonal nature on a string quartet than I would

on the piano. I think it’s to do with harmonics; with the pedal, you

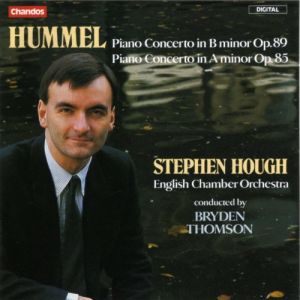

activate many harmonics on the instrument. SH: There are always things that one isn’t pleased

with, but I feel slightly lucky, really, to be honest with you. The

first release that came out was the Hummel Concertos, which was a lot smoother as

a session than it should have been in the sense that neither the orchestra

nor myself had played the pieces before. We had to rehearse and record

sessions on two consecutive days, and the conductor didn’t even have a full

score for the B Minor Concerto;

he was just reading off a piano score. And they’re particularly difficult

pieces to play for the instrument. The technical demands are more than

is usual in most piano repertoire, and it’s technique that is not generally

learned anymore — double-note figures that just don’t

get taught because Liszt did away with all that kind of technical brilliance

and invented a much more brilliant way. But I am pleased with the Hummel

record.

SH: There are always things that one isn’t pleased

with, but I feel slightly lucky, really, to be honest with you. The

first release that came out was the Hummel Concertos, which was a lot smoother as

a session than it should have been in the sense that neither the orchestra

nor myself had played the pieces before. We had to rehearse and record

sessions on two consecutive days, and the conductor didn’t even have a full

score for the B Minor Concerto;

he was just reading off a piano score. And they’re particularly difficult

pieces to play for the instrument. The technical demands are more than

is usual in most piano repertoire, and it’s technique that is not generally

learned anymore — double-note figures that just don’t

get taught because Liszt did away with all that kind of technical brilliance

and invented a much more brilliant way. But I am pleased with the Hummel

record. SH: I hope so. I was very fortunate when I

was young — between the ages of about ten and eighteen

— to have a teacher whose main concern was to develop my feelings

about the music, and not to tell me what to do. I don’t quite work

out exactly how he did it, but it was a mixture of extreme modesty and good

sense, and a good sense also of timing. When I started with him at

those early ages, particularly around eleven, twelve, thirteen, he could

have showed me ways to do things that would have sounded better. But

his feeling was that he didn’t want to say, “Do that rubato there; take time

here,” because he wanted me to discover those things for myself so that I

would develop and become mature. I suppose it’s rather like a parent

who, instead of just saying to the child, “You’re not allowed to do that,”

they somehow want to show the child that it’s in their best interests not

to do that.

SH: I hope so. I was very fortunate when I

was young — between the ages of about ten and eighteen

— to have a teacher whose main concern was to develop my feelings

about the music, and not to tell me what to do. I don’t quite work

out exactly how he did it, but it was a mixture of extreme modesty and good

sense, and a good sense also of timing. When I started with him at

those early ages, particularly around eleven, twelve, thirteen, he could

have showed me ways to do things that would have sounded better. But

his feeling was that he didn’t want to say, “Do that rubato there; take time

here,” because he wanted me to discover those things for myself so that I

would develop and become mature. I suppose it’s rather like a parent

who, instead of just saying to the child, “You’re not allowed to do that,”

they somehow want to show the child that it’s in their best interests not

to do that. BD: You must have lots of offers. How do you

decide which engagements you’ll accept and which you will turn down or postpone?

BD: You must have lots of offers. How do you

decide which engagements you’ll accept and which you will turn down or postpone? SH: Yes, but I certainly don’t listen to them with

a view of copying anything. I wouldn’t copy one bar, but one can get

a general feeling. Rather than that, the problem is that one is hampered

by many recent performances of the concertos. With the big tune at

the end, we’ve fallen into a tradition of playing it very slow. It’s

become more and more slow and more and more pompous and heavy, and there’s

a lot of variety of texture and touch in Rachmaninoff. He was a great

pianist. He did not just sit down and pound away for half an hour.

He had, we’re told, one of the greatest tonal palates of pianists of all

time. One thing he could do as well as anyone else was to play a true

leggiero. You hear his

recordings of something like his own transcriptions of the Liebesfreud and Liebesleid of Kreisler, and many of the

solo works. They have that snappy kind of rhythm; there’s no sogginess

there. It has a bite, a lift. I’m trying very much to look at

the piece myself from the score, but also to just get away from all the tradition

that’s grown up recently, and try a little bit to get back to the source.

SH: Yes, but I certainly don’t listen to them with

a view of copying anything. I wouldn’t copy one bar, but one can get

a general feeling. Rather than that, the problem is that one is hampered

by many recent performances of the concertos. With the big tune at

the end, we’ve fallen into a tradition of playing it very slow. It’s

become more and more slow and more and more pompous and heavy, and there’s

a lot of variety of texture and touch in Rachmaninoff. He was a great

pianist. He did not just sit down and pound away for half an hour.

He had, we’re told, one of the greatest tonal palates of pianists of all

time. One thing he could do as well as anyone else was to play a true

leggiero. You hear his

recordings of something like his own transcriptions of the Liebesfreud and Liebesleid of Kreisler, and many of the

solo works. They have that snappy kind of rhythm; there’s no sogginess

there. It has a bite, a lift. I’m trying very much to look at

the piece myself from the score, but also to just get away from all the tradition

that’s grown up recently, and try a little bit to get back to the source.Stephen Hough

With an artistic vision that transcends musical fashions and trends, Stephen Hough is widely regarded as one of the most important and distinctive pianists of his generation. In recognition of his achievements, he was awarded a prestigious MacArthur Fellowship in 2001, joining prominent scientists, writers and others who have made unique contributions to contemporary life. He received the 2008 Northwestern University School of Music's Jean Gimbel Lane Prize in Piano Performance and was the 2010 winner of the Royal Philharmonic Society Instrumentalist Award. Mr. Hough has appeared with most of the major American and European orchestras and plays recitals regularly in the important halls and concert series around the world. Recent engagements include recitals in London, Paris, Hong Kong, Sydney, Chicago and San Francisco; performances with the New York, London, Los Angeles and Czech Philharmonics, the Chicago, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, St. Louis and Toronto symphonies, the Cleveland, Philadelphia, Minnesota and Russian National Orchestras; and a performance televised worldwide with the Berlin Philharmonic and Sir Simon Rattle. Stephen Hough is also a regular guest at festivals such as Salzburg, Ravinia, Tanglewood, Blossom, Hollywood Bowl, Edinburgh, Aldeburgh and the BBC Proms, where he has made over 20 appearances. In the summer of 2009 he played all of the works for piano and orchestra of Tchaikovsky over four Prom concerts, three of which were broadcast live on BBC television. During the summer of 2012 he returns to the Aspen, Grand Teton and Lincoln Center's Mostly Mozart Festivals. Highlights of Mr. Hough's 2012/13 season include re-engagements with the Boston, San Francisco, Houston and Baltimore symphonies as well as with the Hong Kong Philharmonic and Deutsche Symphony Orchestra Berlin and solo recitals in Carnegie Hall, Vancouver, St. Paul and London's Barbican Center. He will also be the Artist-in-Residence with the BBC Symphony in London. Stephen Hough's catalogue of over 50 CDs has garnered numerous international prizes, including the Deutsche Schallplattenpreis, Diapason d'or, Monde de la musique, four Grammy nominations and eight Gramophone Magazine Awards, including 'Record of the Year' in 1996 and 2003 and the Gramophone "Gold Disc" Award in 2008. His most recent recordings are the Grieg and Liszt Concertos for Hyperion and a disc of his own compositions for BIS Records. He records the two Brahms concertos with the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra in January 2013. An avid writer, Stephen Hough frequently writes for many of the major London newspapers such as The Guardian, The Times, and was invited by the Daily Telegraph in 2008 to start what has become one of the most popular cultural blogs. He has also written extensively about theology and his book, The Bible as Prayer, is published in the US and Canada by Paulist Press. As a composer, Mr. Hough has been commissioned by the musicians of the Berlin Philharmonic, London's National Gallery, Westminster Abbey, Wigmore Hall, Le Musée de Louvre and Musica Viva Australia among others. He premiered his Sonata for Piano (broken branches) at Wigmore Hall in June 2011 and the world premiere of his Missa Mirabilis, commissioned by the Indianapolis Symphony, took place in April 2012. Mr. Hough's numerous compositions for solo piano, chamber ensembles, orchestra and voice are published by Josef Weinberger Ltd. A resident of London, Mr. Hough is a visiting professor at the Royal Academy of Music in London and holds the International Chair of Piano Studies at his alma mater, the Royal Northern College in Manchester. For further information please visit www.stephenhough.com |

This interview was recorded in his studio at the Ravinia

Festival in Highland Park, IL, (the summer home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra)

on July 3, 1989. It was used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1990,

1991, 1996 and 1999. It was transcribed and posted on this website

in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.