|

Opera Star Dorothy Kirsten Dies; Led

Alzheimer's Fight

November 19, 1992 | BURT A.

FOLKART | LOS ANGELES TIMES STAFF WRITER

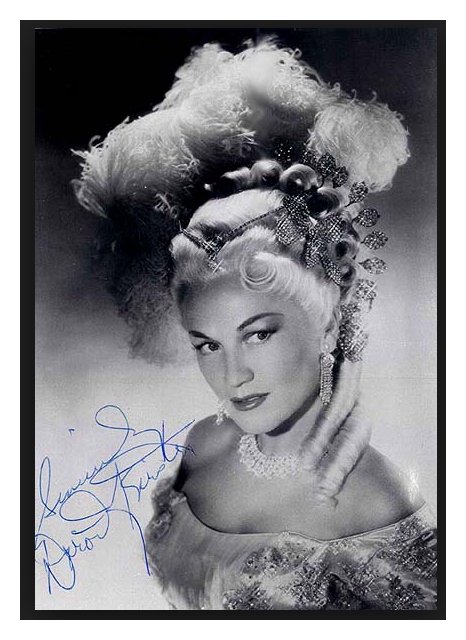

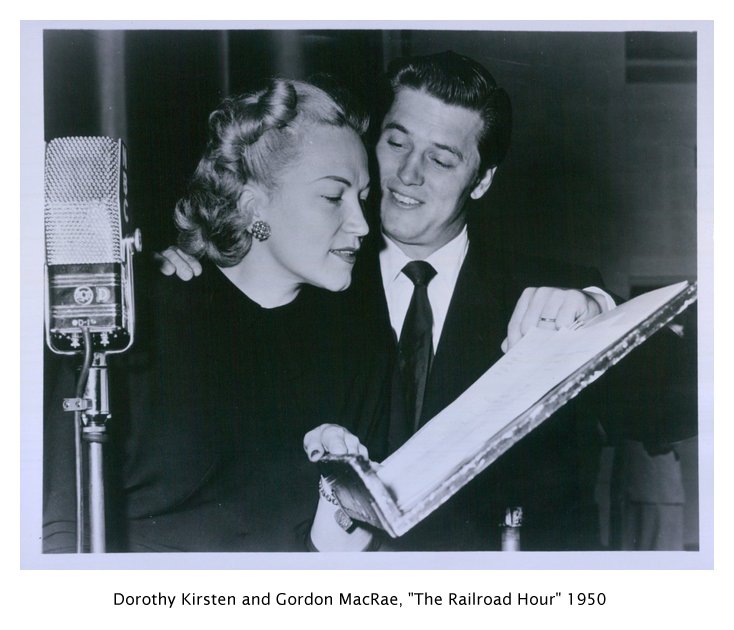

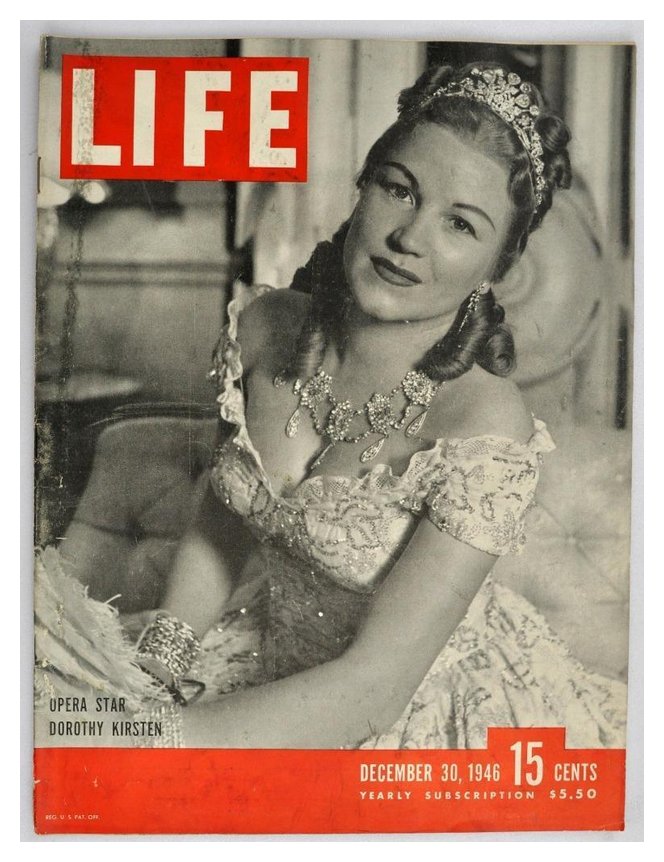

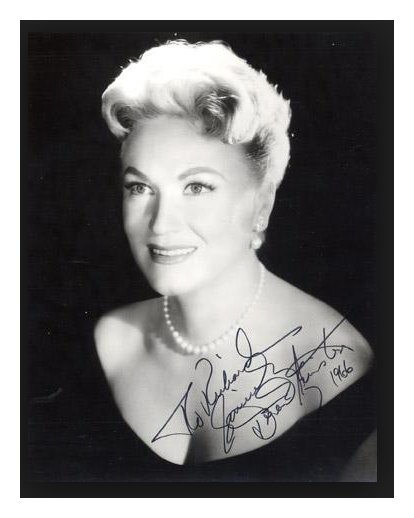

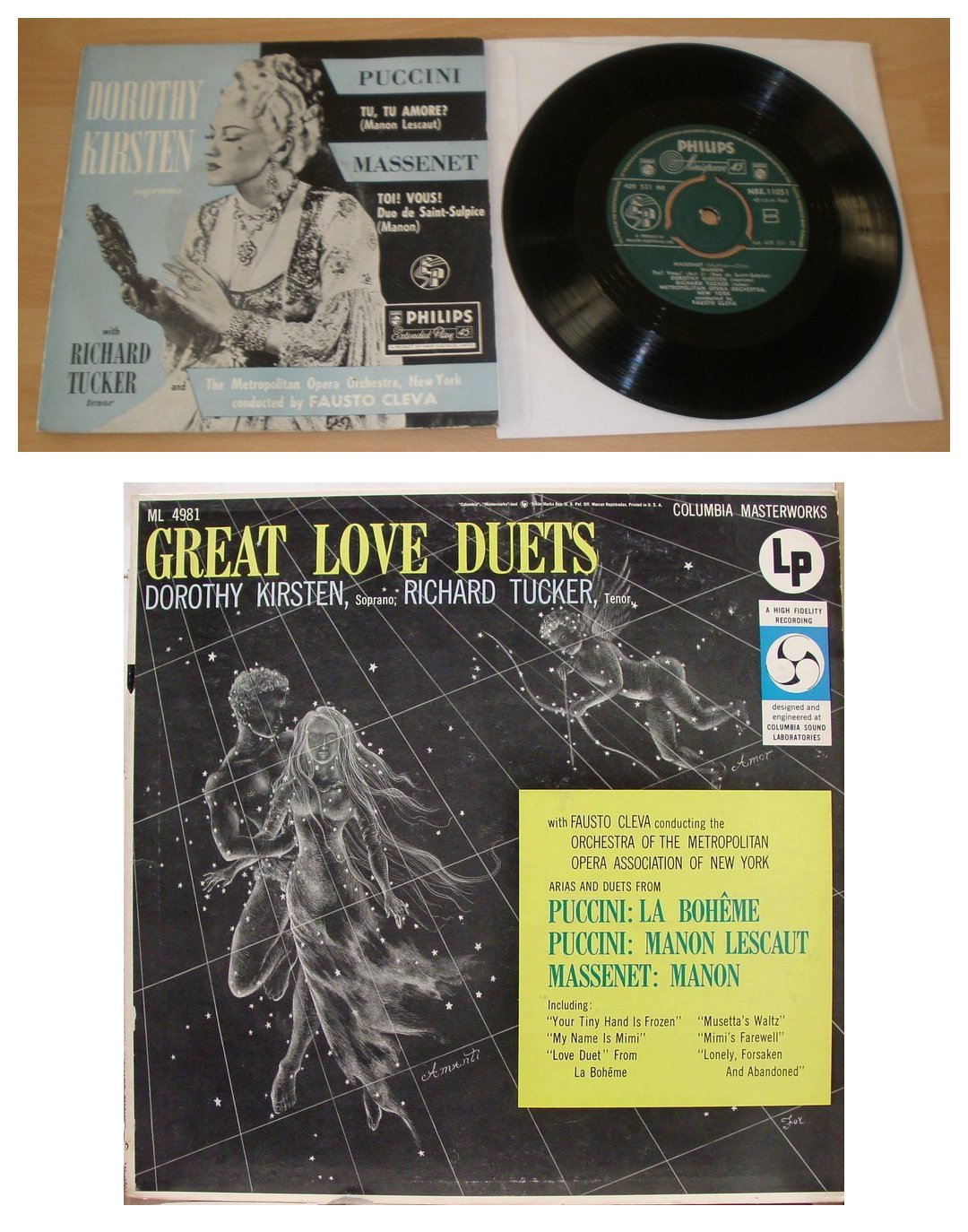

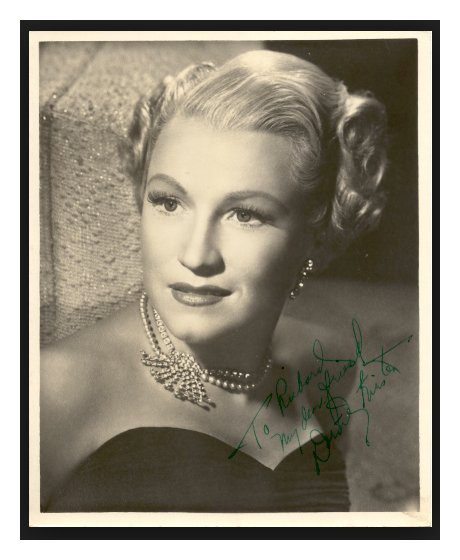

[Text only - photos from another source] Dorothy Kirsten, the glamorous and gifted lyric soprano considered the definitive "Madama Butterfly" of her era, died early Wednesday at UCLA Medical Center where she had been hospitalized for several days following a stroke. The radiant singer, who brought sophisticated American charm and glamour to the musical world when many opera stars of the day were more pleasing to the ear than they were to the eye, was 82. Although she was the first opera star to appear on the cover of Life magazine and the first singer in the history of the Metropolitan Opera to sing on that stage for 30 consecutive years, she became even better known in her final years for her dedication to finding a cure for the illness that killed her husband. Dr. John D. French, whom she married in 1955, died in 1989 of the complications of Alzheimer's disease. Ironically he was the neurologist who had founded the UCLA Brain Research Institute. Shortly after he was stricken in 1982 and retreated into whatever faraway places the crippled mind dwells, Miss Kirsten told The Times, "I pray God will take him from me before it becomes necessary to put him in a home." She finally had to put him in one, but it was a home and center she herself had founded in 1983 and which has since raised more than $3.5 million to support Alzheimer's research. Since 1988 the center has underwritten the Bulletin of Clinical Neurosciences and sponsored more than 30 seminars in the United States and Europe where Alzheimer's researchers have shared their knowledge. In 1987 the John Douglas French Center for Alzheimer's disease opened in Los Alamitos and it was there that Dorothy Kirsten French's husband spent his final days. Even after his death the center had remained a preeminent part of her life. A spokesman for the center recalled shortly after her death a trip he had taken with her to Massachusetts General Hospital in Cambridge where she made one of many presentations on behalf of the facility named for her husband. Adding a personal note to the proceedings, a couple of the doctors there told her of the days when they were young medical students and had journeyed to New York where they stood to hear her sing at the Met because they lacked the funds for opera seats. "Gentlemen," she said, "thank you, but we're here to discuss Alzheimer's." French Foundation Chairman Art Linkletter said at her death, "Dorothy's dynamic spirit has been an inspiration to all of us. Her memory will continue to motivate us in our gallant fight against Alzheimer's disease."  Dorothy Kirsten, who attributed her vocal longevity to recognizing early on that she had a pleasingly clear but not overwhelming lyric soprano voice, was born in Montclair, N.J. She studied piano as a child but didn't take up voice until she was in her teens. And even then she did not consider opera as a career. It was Broadway musicals she had an eye on. She said over the years that she always considered herself "a singing actor rather than an opera singer." She was paying for her vocal lessons and Juilliard studies by appearing on radio and in choral groups backing up such radio stars as Kate Smith. Her silvery voice came to the attention of opera soprano Grace Moore, who became her mentor. Miss Moore sent her to study with Astolio Pescia in Rome and when she was forced to return in 1940 with World War II on the horizon, she had developed professionally to a point where she could make her debut as Pousette in "Manon" with the Chicago Opera. Two years later she made her New York debut with the San Carlo Opera Co. as Mimì in "La Bohème." In 1945 came her Metropolitan debut, again as the frail girl with the cold hands but cheerful spirit. That began a string of 170 Met performances in 12 roles over the next three decades. It was an unprecedented run, one she attributed to her new teacher, Ludwig Fabri, who only allowed her to sing exercises and never arias in his class, thus saving her voice for performances. She remained with him until his death in 1963. When she gave her final Met performance on New Year's Eve in 1975 in the role of Floria Tosca, she had also accumulated 25 seasons with the San Francisco Opera that involved dozens of appearances at the Shrine and Philharmonic auditoriums in Los Angeles. The voice that the late Times critic Albert Goldberg once described as "filled with conviction" had been heard as Manon Lescaut, as Marguerite in "Faust," as Violetta in "La Traviata," as Nedda in "Pagliacci" and in the title role of "Louise," which she learned from Gustave Charpentier, the opera's composer. She had sung on the radio with Frank Sinatra, appeared regularly on TV variety shows and was seen in films with Mario Lanza in "The Great Caruso" and Bing Crosby in "Mr. Music." In recital, her blond hair and stunning, usually white gowns gave her a radiant, angelic look.  |

Believe it or not, on July 6 of this year (1987),

Dorothy Kirsten will be

70! [The Oxford Dictionary of

Opera listed her birth year as 1917; Baker’s Biographical Dictionary (8th Edition)

lists it as 1915; the obituary in The New York Times lists those as

years which had been given by her, but the accurate year was 1910.] Her career in

opera, operetta, radio, and film was long and

distinguished, and she continues to give her knowledge and enthusiasm

to the younger generation. Her views on the current state of the

art, however, are a bit critical. She feels there will continue

to be opera, but it won’t be like it was in her day. “It’s the

responsibility of anyone having a great gift of God that is developed

into being an opera singer,” she says. She herself lived by this

creed, and sacrificed her own family life in order to further and

maintain her brilliant career. “I hesitated until I had the right

man, and by then it was too late to have a family. But if I’d had

a family, I would not have had the rest of my career. It must be

a complete dedication, and without that it can never be the

greatest. And believe me, when you make it to the top, you have

to keep working in order to stay there!”

Believe it or not, on July 6 of this year (1987),

Dorothy Kirsten will be

70! [The Oxford Dictionary of

Opera listed her birth year as 1917; Baker’s Biographical Dictionary (8th Edition)

lists it as 1915; the obituary in The New York Times lists those as

years which had been given by her, but the accurate year was 1910.] Her career in

opera, operetta, radio, and film was long and

distinguished, and she continues to give her knowledge and enthusiasm

to the younger generation. Her views on the current state of the

art, however, are a bit critical. She feels there will continue

to be opera, but it won’t be like it was in her day. “It’s the

responsibility of anyone having a great gift of God that is developed

into being an opera singer,” she says. She herself lived by this

creed, and sacrificed her own family life in order to further and

maintain her brilliant career. “I hesitated until I had the right

man, and by then it was too late to have a family. But if I’d had

a family, I would not have had the rest of my career. It must be

a complete dedication, and without that it can never be the

greatest. And believe me, when you make it to the top, you have

to keep working in order to stay there!”

Since leaving the Met, Kirsten has continued to sing, as

well as direct

a bit, and has even written her autobiography, entitled A Time to Sing,

published by Doubleday. She also was involved in a production of

Tosca in California for which

she designed the sets. Saying she’s

been frustrated by other productions, she included a 12 foot fall for

her jump at the end of the opera. “I wanted realism as much as

possible. That’s what Puccini wrote.” During our phone

conversation, Miss Kirsten was at her home in California, and I was in

my home in Chicago, so I asked her about her very early days in the

Windy City. “I remember I made my debut in Chicago, and the

acoustics there are wonderful. That was in 1940, and I was

Poussette in Manon.” [She was speaking from memory,

but a check of the Annals reveals her recollection to be

accurate. It was November 9, and the cast included Jepson,

Crooks, and Rothier, with Abravanel in the pit. There were two

more performances of Manon that season, both with Schipa, and the last

with Grace Moore in the title role. The previous issues of this

Newsletter contain interviews with both Jepson and Abravanel, as

well

as a few more details about those exciting Chicago seasons. Click

the links to read those interviews, and also see my extensive article Massenet, Mary

Garden, and the Chicago Opera 1910-1932.]

Since leaving the Met, Kirsten has continued to sing, as

well as direct

a bit, and has even written her autobiography, entitled A Time to Sing,

published by Doubleday. She also was involved in a production of

Tosca in California for which

she designed the sets. Saying she’s

been frustrated by other productions, she included a 12 foot fall for

her jump at the end of the opera. “I wanted realism as much as

possible. That’s what Puccini wrote.” During our phone

conversation, Miss Kirsten was at her home in California, and I was in

my home in Chicago, so I asked her about her very early days in the

Windy City. “I remember I made my debut in Chicago, and the

acoustics there are wonderful. That was in 1940, and I was

Poussette in Manon.” [She was speaking from memory,

but a check of the Annals reveals her recollection to be

accurate. It was November 9, and the cast included Jepson,

Crooks, and Rothier, with Abravanel in the pit. There were two

more performances of Manon that season, both with Schipa, and the last

with Grace Moore in the title role. The previous issues of this

Newsletter contain interviews with both Jepson and Abravanel, as

well

as a few more details about those exciting Chicago seasons. Click

the links to read those interviews, and also see my extensive article Massenet, Mary

Garden, and the Chicago Opera 1910-1932.] During this most enjoyable hour, Miss Kirsten also spoke

of her

Puccini roles. She said that Mimì is a simple role

— not to sing,

but dramatically. “She doesn’t know her emotions like Manon or

Butterfly or Tosca.” The singer then recalled Minnie in Fanciulla

del West and said, “It’s the most demanding role Puccini wrote

for the

lyric-spinto voice. I called it my Brünnhilde, and not only

because of the horse!”

During this most enjoyable hour, Miss Kirsten also spoke

of her

Puccini roles. She said that Mimì is a simple role

— not to sing,

but dramatically. “She doesn’t know her emotions like Manon or

Butterfly or Tosca.” The singer then recalled Minnie in Fanciulla

del West and said, “It’s the most demanding role Puccini wrote

for the

lyric-spinto voice. I called it my Brünnhilde, and not only

because of the horse!”© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on June 26,

1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following

year,

and again in 1987, 1990 and 1995.

This transcription was made and published in the semi-annual Massenet Newsletter in July,

1987. It was slightly re-edited and expanded in 2016, and posted

on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.