By Bruce Duffie

| What is contained on these three

webpages is an expanded version of an article which was first published the

Masssenet Newsletter dated

January, 1984. A semi-annual of the Massenet Society, thirty-two of

my interviews were presented there from 1982-1993, but this was my only researched-article

for them. A similar arrangement was made with Wagner News, published by the Wagner

Society of America, where forty-five interviews and five articles appeared

between 1980-1992, including a presentation very similar to

this one about Wagner in Chicago during the same period of the teens

and twenties. As you will see, this is a very logical time segment

to examine, and in some cases the singers overlapped into both repertoires. It is now exactly thirty years later, and many of my interviews are being posted on this website. So I felt it time to re-examine this article, update it a bit and give it another life! Originally the text and performance chart were published, but here I have added a new chart regarding tours, and have updated the original chart to include more names where possible. I have also now included biographies and photographs of most of the singers and conductors. There are five basic sources for all of this. Three books, a generous collection of clippings, and the ubiquitous world wide web. Specifically, -- Opera in Chicago - A Social and Cultural History

1850-1965 by Ronald Davis

-- Forty Years of Opera in Chicago by Edward Moore -- Oscar Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera Company by John F. Cone -- A collection of scrapbooks kept by [unknown] from 1922-1937 -- The internet and its all-encompassing trove of text material and photographs * *

* * *

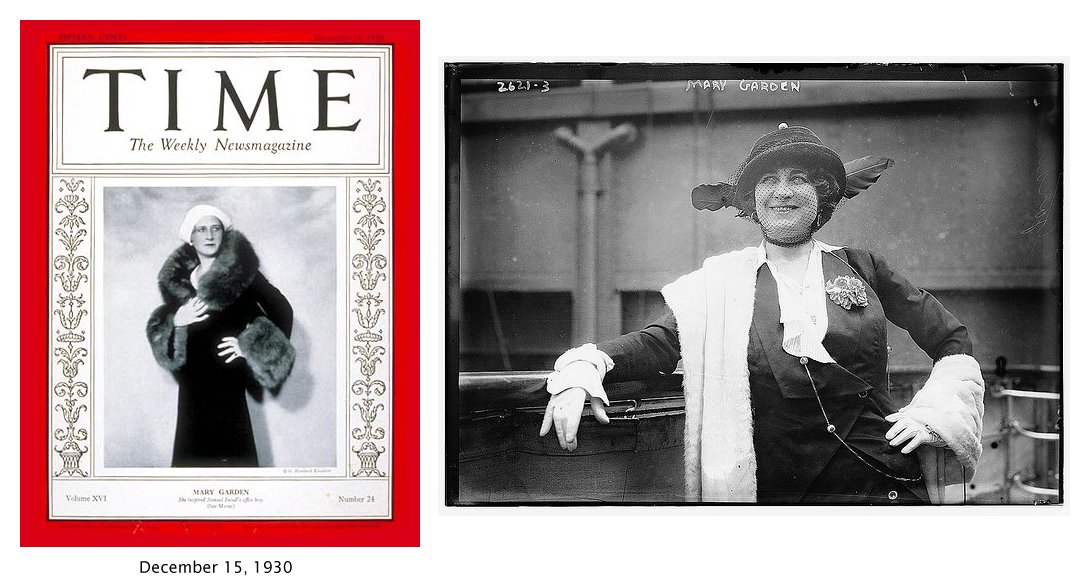

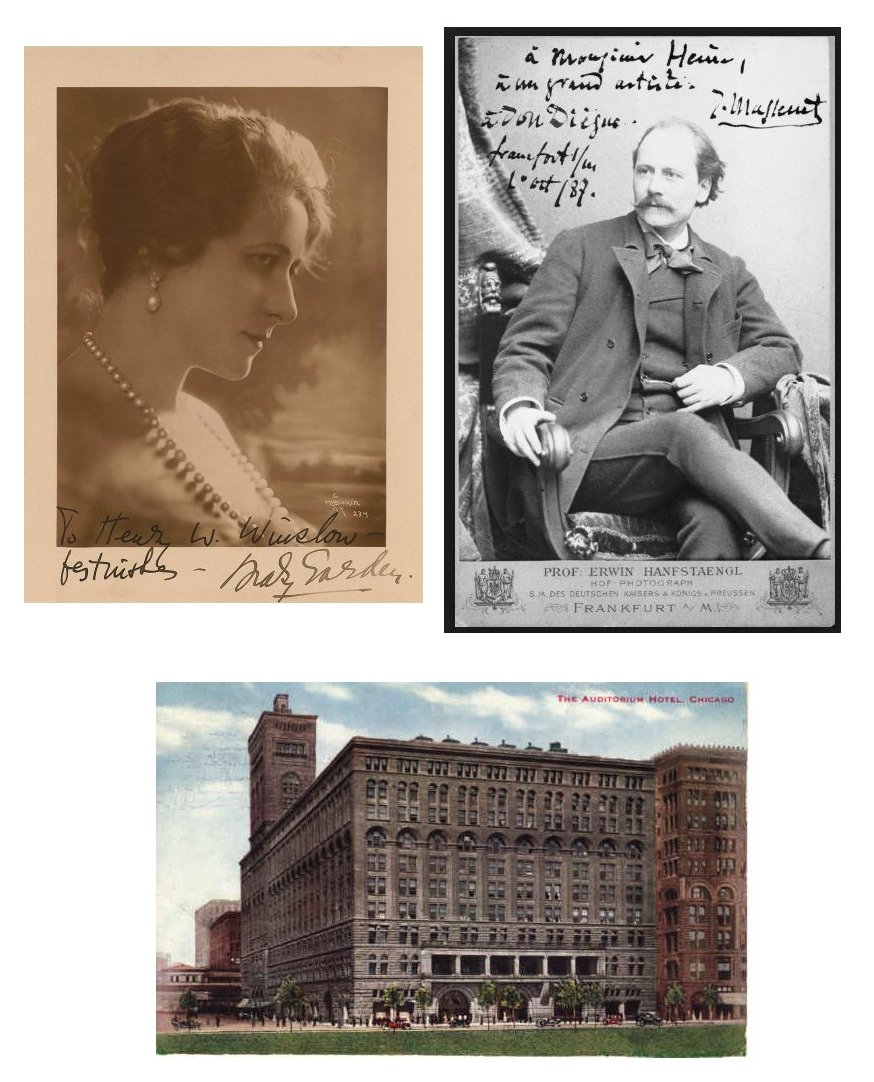

The presentation is organized in the following manner. There are three webpages, with a link to the next page at the bottom of the first two. On the first page (this page)... -- The title and a photo group of Mary Garden, Massenet, and the Auditorium Theater of Chicago -- An introduction (this box), followed by another photo of Massenet -- The original text, slightly edited, with the addition of various photos, an "appendix" and other related items -- The original chart of performances and casts, greatly expanded with more names as well as the "prologue" for the years 1906-10 and a brief "epilogue" -- A new chart (in the same order) showing tour cities where each opera was done in the years 1907-29 -- Materials for each opera (in the same order) with programs, photos, commentary, etc., including a few of the illustrated biographies where appropriate -- A long, illustrated biography of Mary Garden (which includes part of an essay she wrote on the art of singing) -- A long, illustrated biography of Charles Dalmorès (which includes a day-to-day schedule illustrative of these principal singers) On the second page... -- An alphabetized list of all the singers, conductors and administrators whose illustrated biographies are contained in this presentation -- The illustrated biographies of the female singers invloved in the opera companies during this period On the third page... --The illustrated biographies of the male singers, as well as the illustrated biographies of the conductors and administrators |

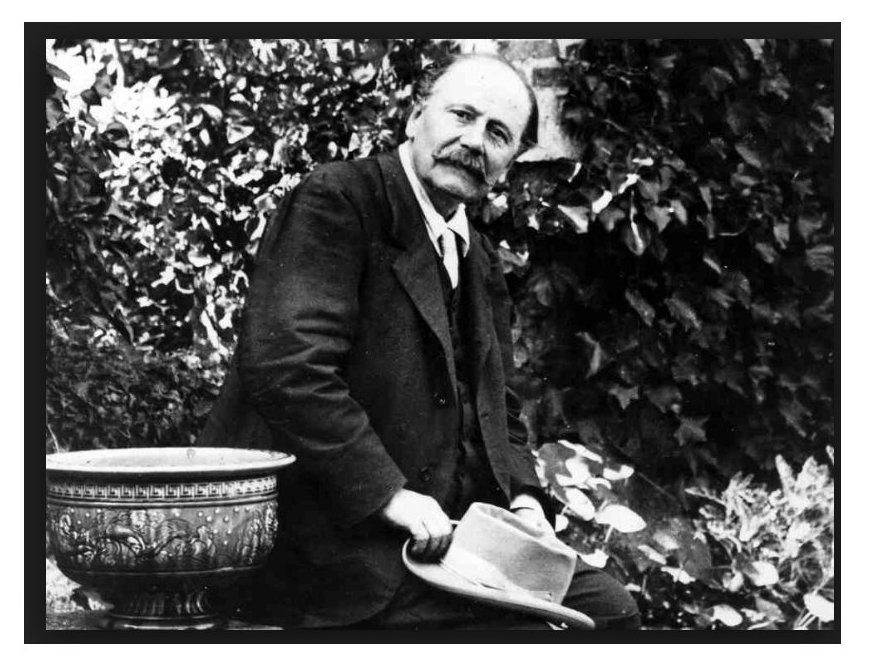

This study originally grew out of a lecture which I gave a few years ago before a performance of Don Quichotte. In digging for material about this little-known work, I began looking through a book called Opera In Chicago by Ronald L. Davis. The book is in two sections. First, a narrative describing the growth and development of the various opera companies in Chicago, and second, the annals of performance from 1910-1965.

Reading through the narrative of the very early days of opera in Chicago is, naturally, fascinating and enlightening. But it is not until one begins to look closely and analytically at the annals that the full impact of those glorious days becomes apparent.

I mentioned that this was for a lecture on Don Quichotte. After noting that

the work had been given in two early seasons -- 1913 and 1929 -- I remembered

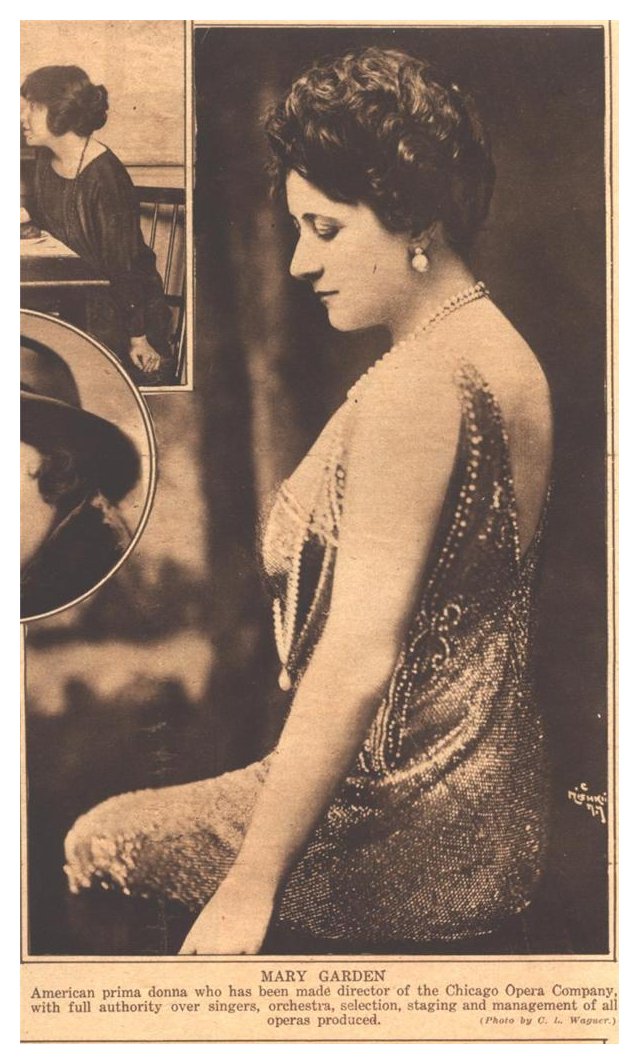

that Mary Garden had been the reigning star of the company, and for one season

had been the General Director. I also knew that she sang much French

repertoire and many modern works. A brief look at a few pages of the

book revealed numerous works with her name, including performances of the

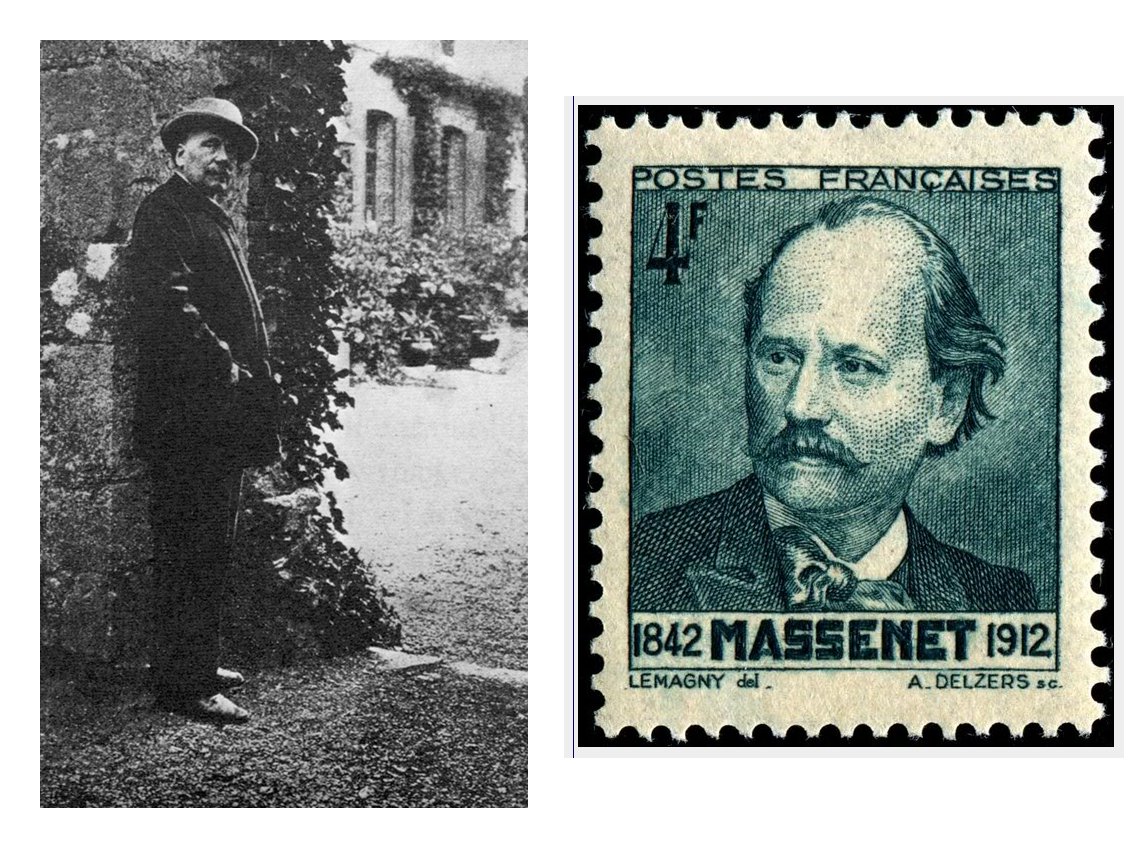

operas of Massenet. So I got to wondering just how much Massenet had

been done by the various Chicago companies, and to my surprise and delight

I found that during the period 1910-32, at least one -- and often several

-- of his works had been presented in every season except one. Then

I hunted for the name of Mary Garden and found that from 1910-1931, she appeared

in all but one season, and in every season except two she sang at least one

Massenet opera!

I mentioned that this was for a lecture on Don Quichotte. After noting that

the work had been given in two early seasons -- 1913 and 1929 -- I remembered

that Mary Garden had been the reigning star of the company, and for one season

had been the General Director. I also knew that she sang much French

repertoire and many modern works. A brief look at a few pages of the

book revealed numerous works with her name, including performances of the

operas of Massenet. So I got to wondering just how much Massenet had

been done by the various Chicago companies, and to my surprise and delight

I found that during the period 1910-32, at least one -- and often several

-- of his works had been presented in every season except one. Then

I hunted for the name of Mary Garden and found that from 1910-1931, she appeared

in all but one season, and in every season except two she sang at least one

Massenet opera!Let me state right here that going through the annals of performance for any great opera company is as frustrating as it is fascinating. When one is familiar with the names and reputations of so many singers -- through reading books and reviews, and from listening to commercial recordings and air-checks -- one can (as I did) become completely bowled over by the repertoire and the casting combinations. There were many times when I simply spent hours looking over the lists, flipping from one season to another, checking to see if the cast was repeated or changed within a season, and seeing who reprised roles from year to year. Every time I would begin running something down, my eyes would catch something equally fascinating and I'd be off on another track for many minutes. And remember that each of these new tangents would usually provide additional side-trackings, so before long the original hunt was completely enmeshed in the maze of past performances. Isn't there a potato chip that claims you cannot eat just one?

Anyway, only after many hours of hunting does any series of patterns become clear, and one can finally get down to the business of sorting through it all with any semblance of satisfaction. I finally decided to make a chart, and that is reproduced farther down on this webpage. I have selected the years 1910-1932 for several specific reasons. First, the start date was simple for 1910 was the first year of resident opera in the city of Chicago. There had been opera before that, but always by touring companies and visiting artists. As with the earliest days of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, there were years in which no opera was given for one reason or another. In Chicago, the year 1914-15 had no opera by a resident company. The same was true for 1932-33, 1943-44, and the bleak period of 1947-53. It should be noted here that Chicago is often compared with San Francisco, and rightly so because of the traditions, size of houses, and specific length and time of the seasons. But the current company, Lyric Opera of Chicago, gave its first performances in 1954, and all current dating and company premieres are for this company. Often, when people hear of Lyric's upcoming 30th season or note that a certain well-known opera is a "Lyric Premiere," they fail to remember that Chicago has had resident opera since 1910. There are the gaps which I mentioned, and there were different companies with slightly different names, but Chicago has had ten more seasons of resident opera than San Francisco. The west coast, though, has been fortunate to still be the same company with no gaps in their yearly annals. Incidentally, Lyric did have one dark year, 1967, but that was an interruption, not a change in the management or name.

For the record, in these pre-1947 years the companies usually changed due to bankruptcy or upheaval in management. Specifically, the correct dates and titles are:

Chicago Grand Opera Company, 1910-1914

Chicago Opera Association, 1915-1921

Chicago Civic Opera, 1921-1932

Chicago Grand Opera Company (again), 1933-1935

Chicago City Opera, 1936-1939

Chicago Opera Company, 1940-1946

Chicago Opera Association, 1915-1921

Chicago Civic Opera, 1921-1932

Chicago Grand Opera Company (again), 1933-1935

Chicago City Opera, 1936-1939

Chicago Opera Company, 1940-1946

Even Lyric Opera of Chicago began in 1954 as the Lyric Theatre, and then changed its name to the present title when the management was re-structured in 1956 under Carol Fox.

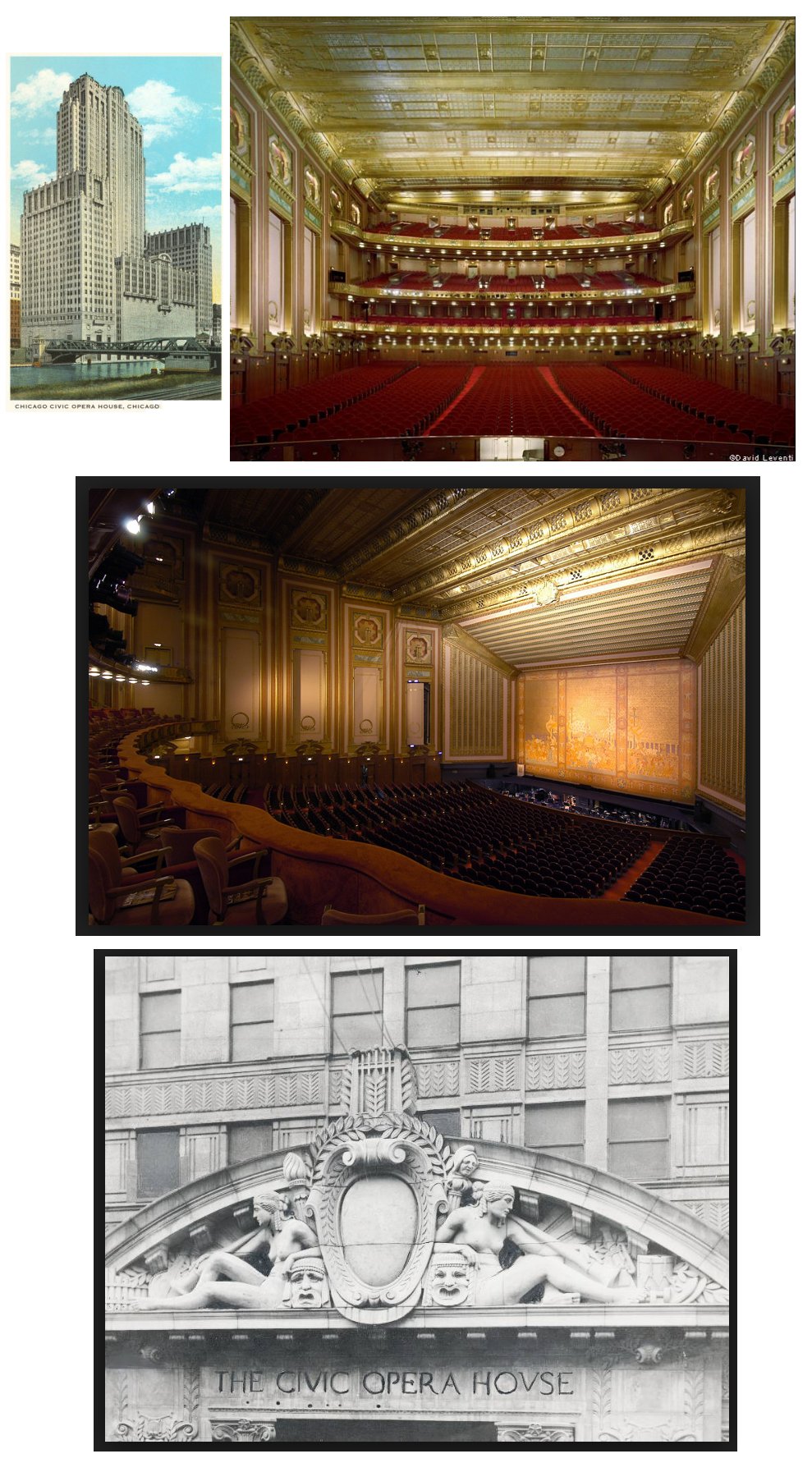

To get back to the subject at hand, the time span of my chart stops after the 1931-32 season. The following year was a gap; Mary Garden was no longer appearing; the company had moved (in November of 1929) to the new Civic Opera House on Wacker Drive, which meant that few of the old sets could be used without major revisions. Further, the companies which presented opera during 1933-47 restricted the works of Massenet to just two - Manon, done is eight seasons with various casts including Moore, Jepson, Sayão, Kiepura, Crooks, Schipa, Brownlee, and Thaïs in three seasons 1935-37, always with Jepson, Martin, and John Charles Thomas. [See the "Appendix" immediately below for more details.] Indeed, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, opera was viewed by the management and patrons as escapism, and few modern works were presented.

So it can be plainly seen that the range of interest to the Massenet Society is clearly centered in the years 1910-1932 with the proliferation of his works and the appearances of Mary Garden.

|

"Appendix"

showing the works of Massenet given in Chicago between 1933 and 2013

[Seasons listed as "19xx-xx" were

longer and ran into the following calendar year.

Those seasons with just a single year-date were shorter and presented operas just in the fall.] [From 1933-45, Manon usually was done twice per year, and Thaïs received just one performance per season.] 1933-34 Manon with Claire, Borgioli, Defrère, Sjovik; Weber 1934 Manon with Hampton, Bentonelli, Royer; Kopp 1935 Thaïs with Jepson, Thomas, Martin, Cordon; Hasselmans 1936 Manon with Dosia/Moore, Burdino, Brownlee; Hasselmans Thaïs [same as 1935 except Ruisi for Cordon] 1937 Thaïs [same as 1936] 1938 Manon with Dosia, Burdino, Royer; Hasselmans 1939 Manon with Moore/Dosia, Burdino/Kiepura, Czaplicki; Hasselmans 1940 Manon with Jepson, Crooks/Schipa, Czaplicki, Kirsten as Pousette; Abravanel/Kopp 1942 Manon with Jepson, Crooks, Czaplicki; Kopp 1945 Manon with Sayão, Tokatyan, Bonelli/Brownlee; Cleva 1959 Thaïs with Leontyne Price, Roux, Simoneau, Corena, Ardis Krainik as Myrtale; Prêtre, directed by Vladimir Rosing 1971 Werther with Troyanos, Kraus, Angot, Andreolli; Fournet, Mansouri 1973 Manon with Zylis-Gara, Kraus, Patrick, Gramm; Fournet, Deiber 1974 Don Quichotte with Ghiaurov, Cortez, Foldi; Fournet, Tajo 1978 Werther with Minton, Kraus, Nolen; Giovaninetti, Samaritani 1981 Don Quichotte with Ghiaruov, Valentini-Terrani, Gramm, Gordon, Negrini, Cook; Fournet, Samaritani, Tallchief 1983 Manon with Scotto, Kraus, Titus, Washington; Rudel, Hebert 1992-93 Le Cid (in concert form) with Domingo, Vernet, Lloyd, Hagley; Delacôte 1993-94 Don Quichotte with Ramey, Mentzer, Lafont; Nelson, Koenig 2002-03 Thaïs with Fleming, Hampson, Kaasch, Morscheck; Davis, Cox 2008-09 [Opening Night] Manon with Dessay, Kaufman, Feigum, Aceto, Cangelosi; Villaume, McVicar 2012-13 Werther with Koch, Polenzani, Verm; Davis, Negrin -- Names which are links here and in

the text refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website

|

* *

* * *

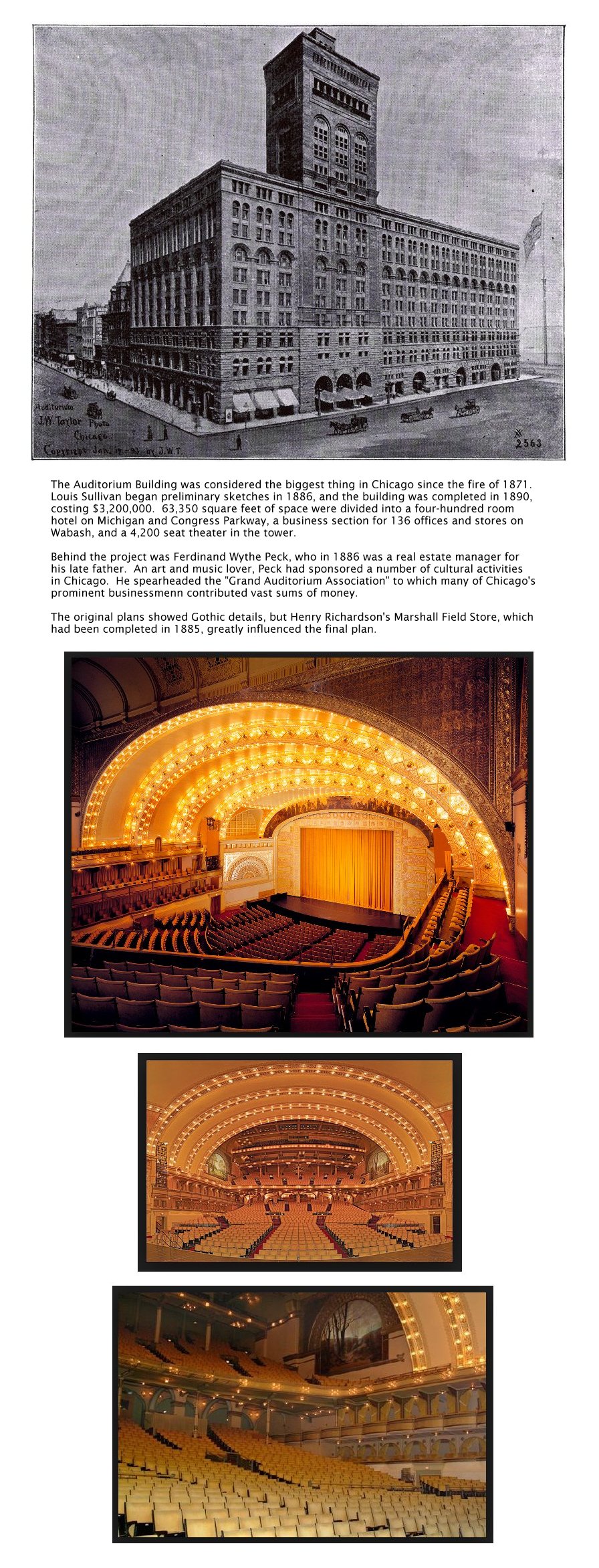

Chicago first heard opera in July of 1850. A group of four singers came by boat from Milwaukee to perform La Sonnambula. The theater burned down the next night (with no loss of life), but opera had been heard and seen and was now demanded by the public. By the 1890s, Chicago was the railway transfer point for just about everyone, and as the hub of the nation it heard opera in the newly-opened Auditorium Theater on Congress Parkway. This historic landmark was considered by Jean De Reszke to have the finest acoustics of any theater in the world!

In 1893, the Columbian Exposition focussed world-wide attention on the city, and many touring companies presented their troupes. On the French front, one of the early artistic triumphs was a production of Le Cid in 1897, and this led to "seasons" of French operas from New Orleans in 1899 and 1900. But something was happening in New York City which would change the course of opera in Chicago.

The story of the Hammerstein Opera Company in New York City is well-known,

and the four seasons he presented were so spectacular that the Met finally

paid him to cease competing with their company. In the settlement,

the Metropolitan Opera Company acquired the assets of the Hammerstein Company

-- which included scores, sets, and costumes for the predominantly French

repertoire. It was at this time that the financiers and backers from

Chicago were trying to get a resident opera company started, and since it

was felt in New York that Chicago would not be directly competing with the

Met, the newly-acquired assets were sent west to help start the Chicago Grand

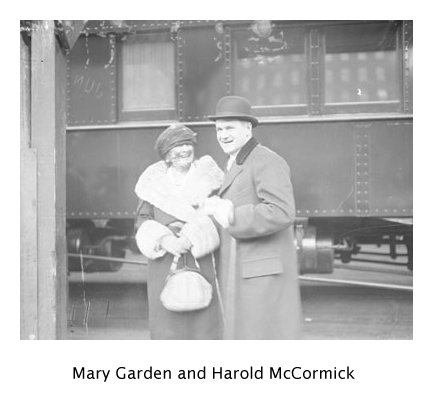

Opera Company. Harold McCormick was the President of the new company,

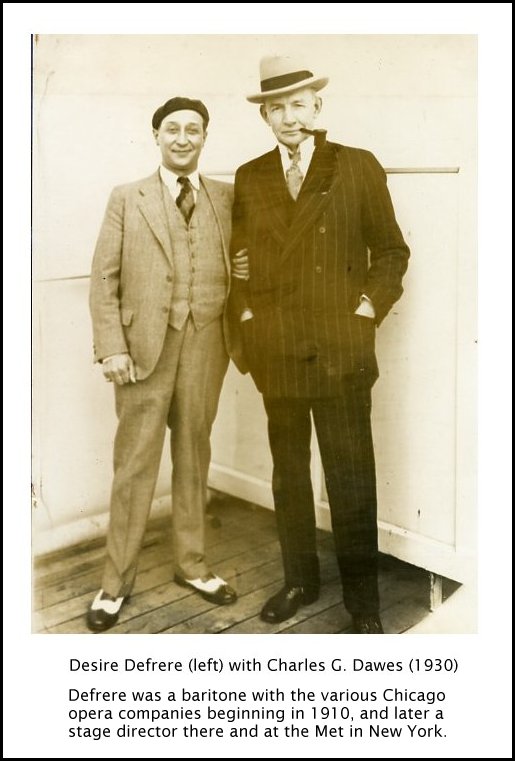

Charles Dawes (later vice-president under Coolidge) was the First Vice-President

[shown in photo at right], Otto

Kahn (then President of the Met) was Second Vice-President. Andreas

Dippel, a former singer and then assistant to Gatti-Casazza at the Met was

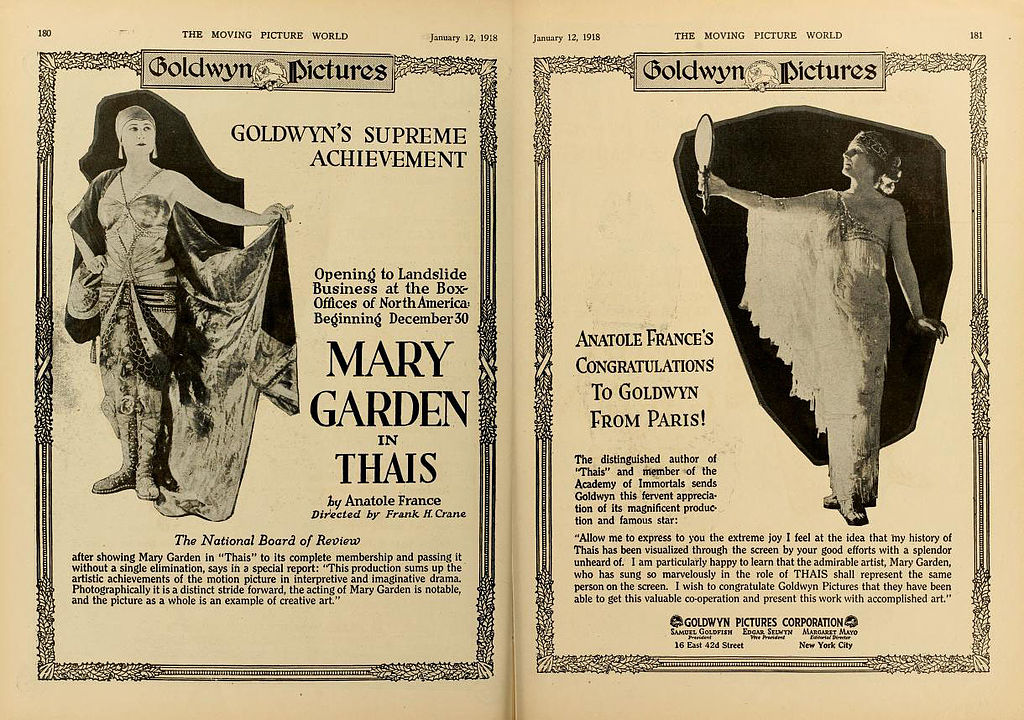

named General Manager, and the leading star of the company was Mary Garden.

The story of the Hammerstein Opera Company in New York City is well-known,

and the four seasons he presented were so spectacular that the Met finally

paid him to cease competing with their company. In the settlement,

the Metropolitan Opera Company acquired the assets of the Hammerstein Company

-- which included scores, sets, and costumes for the predominantly French

repertoire. It was at this time that the financiers and backers from

Chicago were trying to get a resident opera company started, and since it

was felt in New York that Chicago would not be directly competing with the

Met, the newly-acquired assets were sent west to help start the Chicago Grand

Opera Company. Harold McCormick was the President of the new company,

Charles Dawes (later vice-president under Coolidge) was the First Vice-President

[shown in photo at right], Otto

Kahn (then President of the Met) was Second Vice-President. Andreas

Dippel, a former singer and then assistant to Gatti-Casazza at the Met was

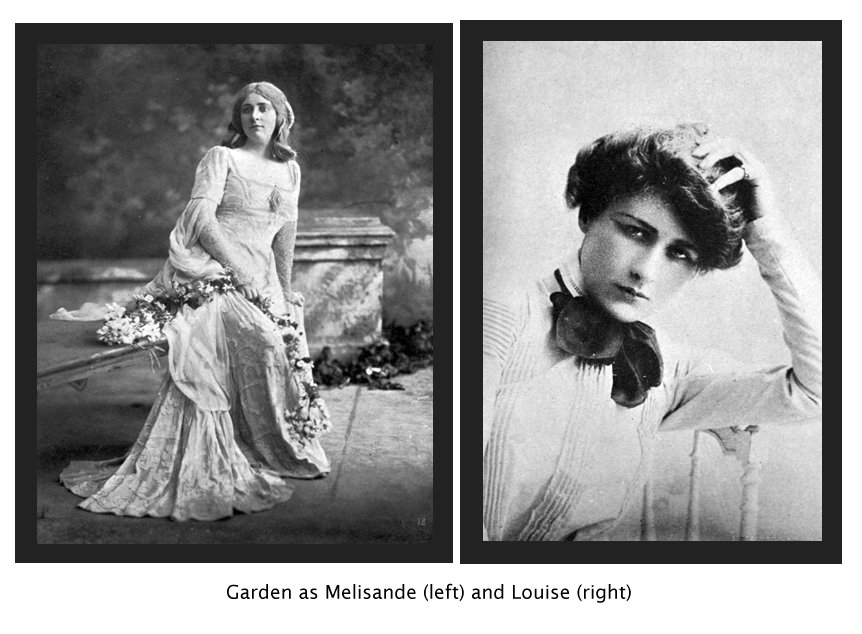

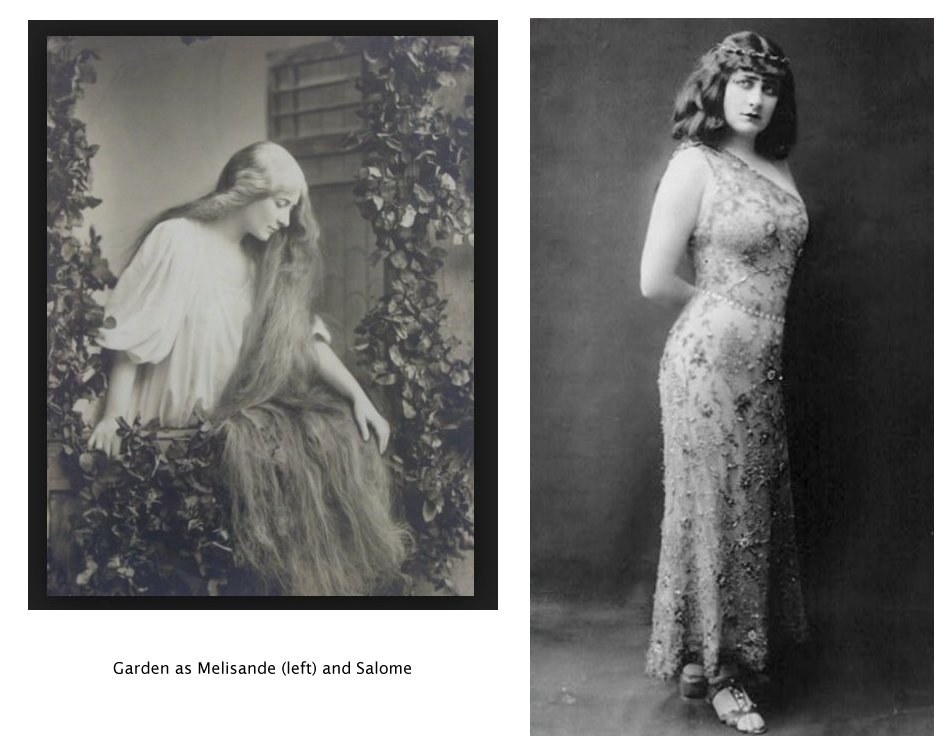

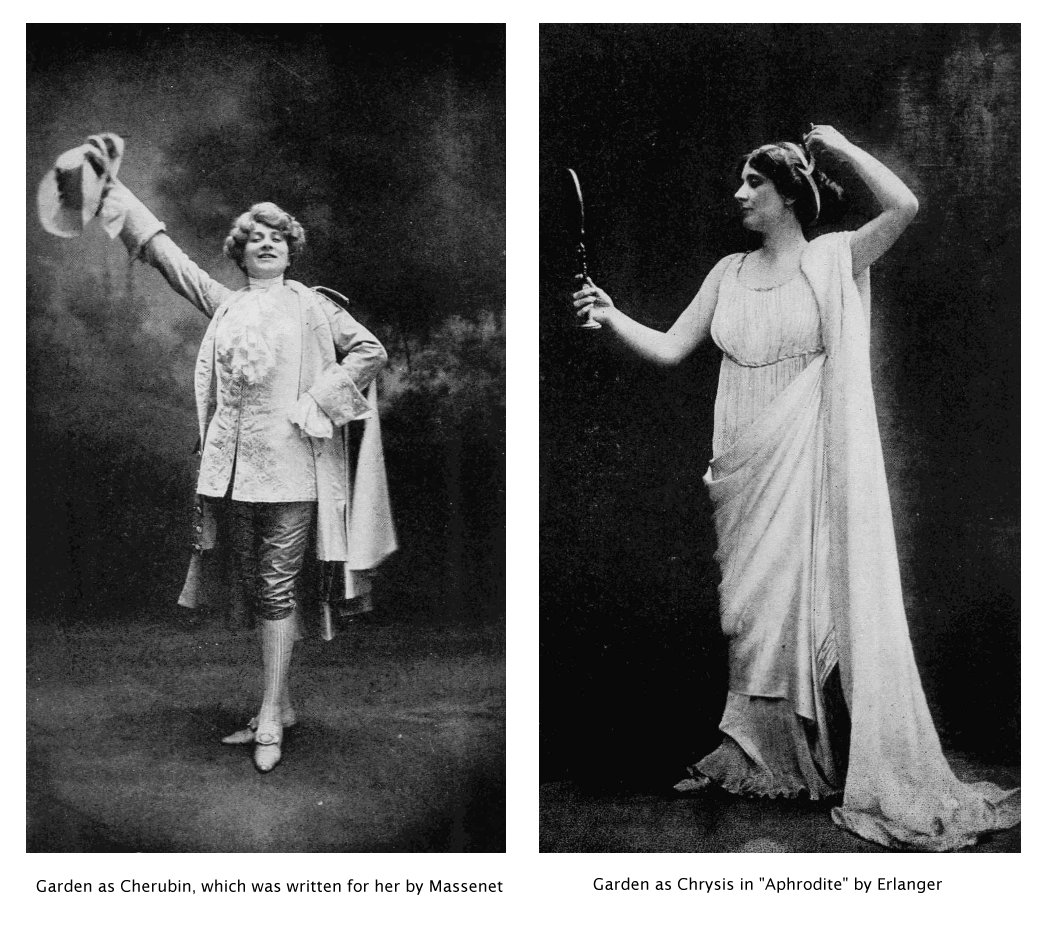

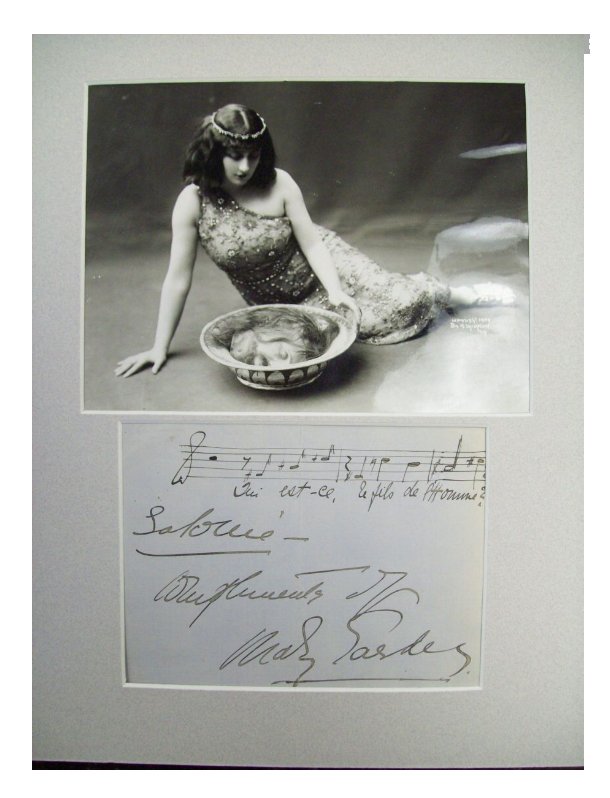

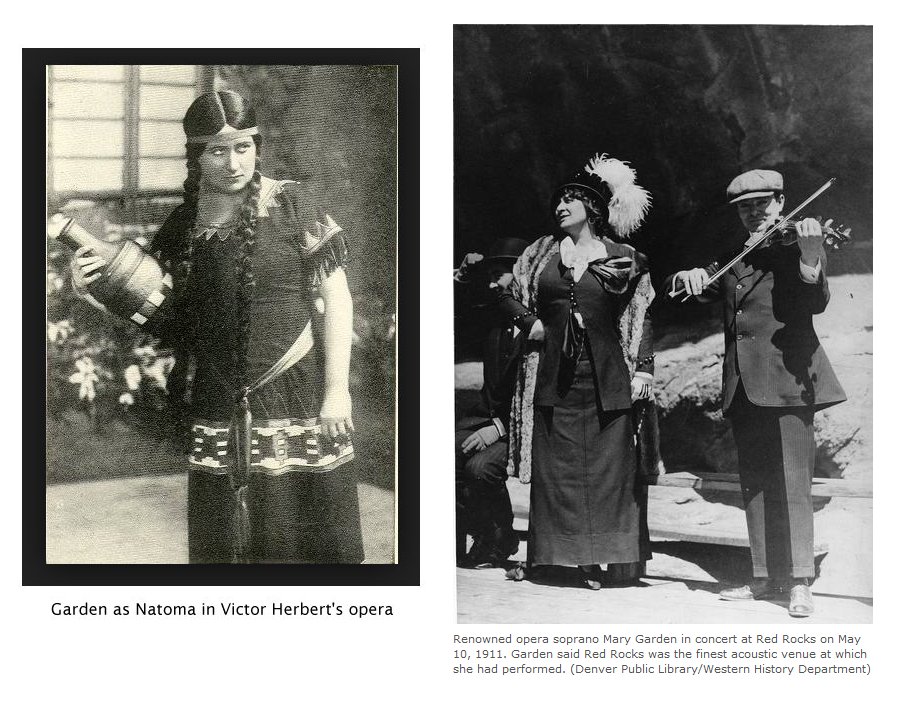

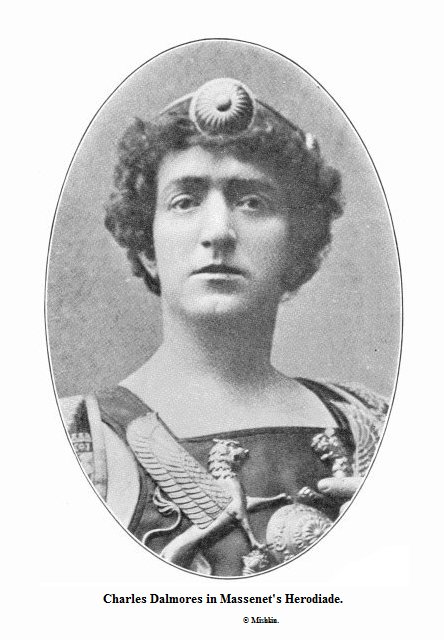

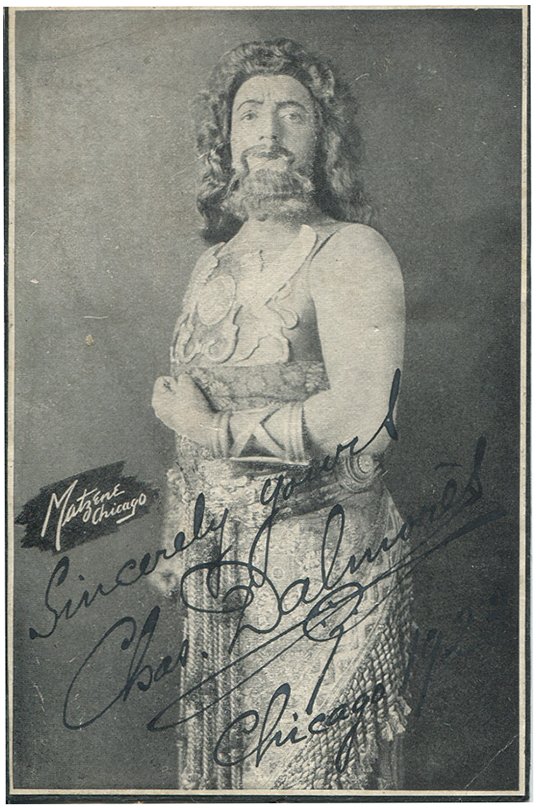

named General Manager, and the leading star of the company was Mary Garden.Just to give some idea as to the glorious sounds heard in that first Chicago season of 1910, Melba sang Mimì and Violetta; McCormack sang Turiddu, Rodolfo, Alfredo, and the Duke; Farrar sang Butterfly; Renaud was the four villains in Tales of Hoffmann; Dalmorès was heard as Faust and Hoffmann; Gadski appeared in Les Huguenots; Caruso sang Pagliacci and Fanciulla del West just six weeks after doing the world premiere in New York -- though other casts had already done four performances, indicating just how up-to-date this brand new company was! Mary Garden sang Mélisande, Louise, Salome (!), Thaïs, and Marguerite. The next season brought Gerville-Réache as Dalila; Tetrazzini was Lucia, Violetta, Gilda, Rosina, and Lakmé; Maggie Teyte was Cherubino and Marguerite as well as Cendrillon; Garden sang Carmen, Natoma, Jongleur, Thaïs, and the Prince in Cendrillon; Dalmorès was Samson, Lohengrin, Siegmund, and Tristan which he sang with Fremstad, Gerville-Réache and Whitehill, and when it came back the following season, Dalmorès and Whitehill were joined by Nordica and Schumann-Heink.

Garden's first opera of that second season (1911-12) was Cendrillon. The Musical Courier said, "Garden is to the French contingent of the opera what Tetrazzini is to the Italian element -- the supreme star -- and her position has not in any way been endangered by the newcomers among the French singers." Both the score and the production came in for applause. The Tribune said, "The scenic display was the most attractive and pretentious ever shown in opera in Chicago."

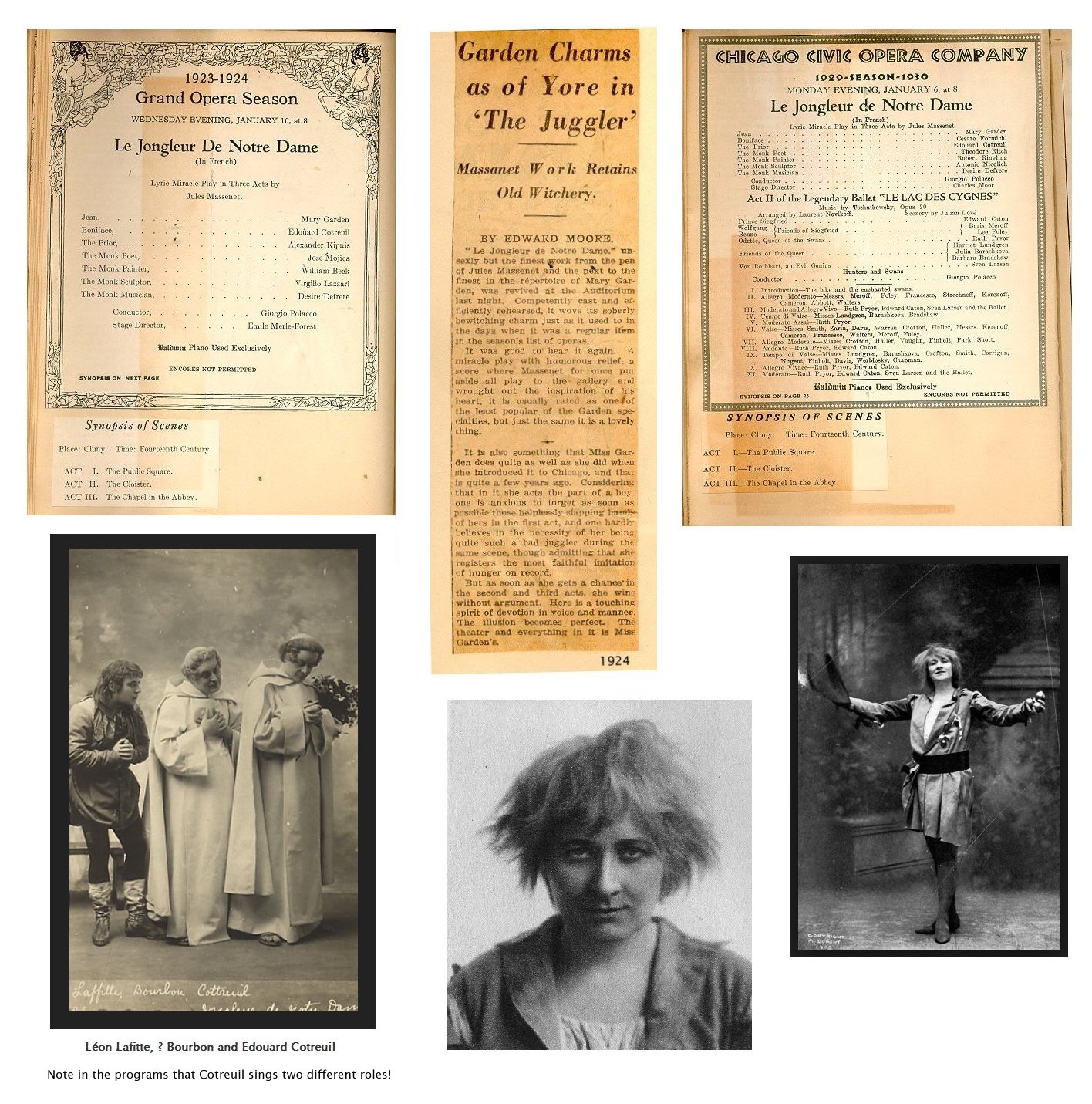

Garden also did Jongleur that second season and it proved one of her very best roles. The part, as we know, was written for a tenor, but had been re-arranged especially for her. She played a young boy, a juggler, and for the part her voice became clear and almost sexless. Dramatically her portrayal was masterly; every movement was intense and realistic. In her autobiography she said of the role, "I danced my country dances, played my fiddle, juggled the three balls, and sometimes I used to let one go and make the people of the village laugh. It made them happier to think I was such a bad juggler. But I was always the boy, excited, and awkward and adoring." The audiences used to get highly amused with the little donkey which followed the young juggler and showed such a great interest in Garden's singing, but looked so totally indifferent when anyone else sang. Some jealous singers claimed that Garden had trained the animal to behave that way . . .

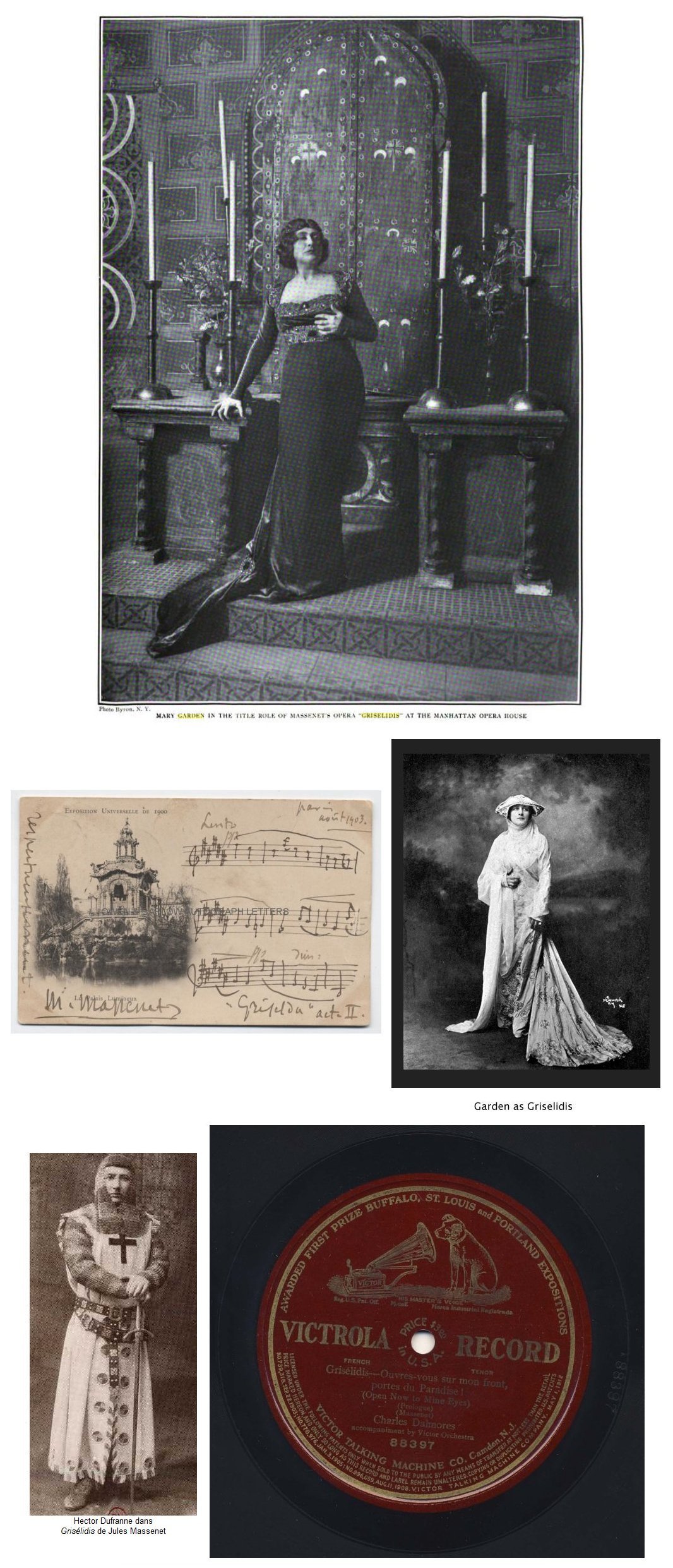

From time to time, there was talk of returning the role to a tenor, but one critic wrote in a later season, "No tenor, no matter how talented, could ever be as boyish as Garden. I would rather hear her sing and then cry and mop her eyes and wipe her nose than listen to the finest tenor on Earth in the part. When the Prior scolds her, she twists her body into something that is all knees and elbows, and it's all boy, too." [Note: While updating this article very late in 2013, I discovered that in 1909-10 David Devriès took part in the final season of Oscar Hammerstein I's Manhattan Opera Company, singing Jean in Jongleur while Garden was away, thus allowing audiences to hear both versions of the opera that season. Garden and Devriès later sang together in both Grisélidis and Pelléas et Mélisande while on tour with the company in Boston.]

The next few years -- during the period specifically concerned here -- in addition to the various Massenet works listed in the chart, Chicago heard Ruffo as Rigoletto, Hamlet, Tonio, Barnaba, Cristoforo Colombo of Franchetti, Figaro, and Don Giovanni; Florence Macbeth sang Olympia, Lucia, Rosina, Gilda, Adina, and Micaëla; Supervia was Mignon and Carmen; Stracciari did roles in Rigoletto, Traviata, Tosca, Ernani, Lucia, and Linda di Chamounix; Homer was Dalila and Amneris; Charles Marshall sang Otello, Tristan, Samson, Riccardo, Alvaro, Enzo, and Pollione; Schipa was in Don Giovanni, Mignon, Don Pasquale, Barbiere, Traviata, Martha, Lucia, Rigoletto, and Sonnambula; Chaliapin was both Boris and Méfistofélès, Galli-Curci was Gilda, Lucia, Violetta, Juilette, Dinorah, Sonnambula, Rosina, Linda di Chamounix, Mimì, and Lakmé; Vanni-Marcoux did roles in Louise, Tosca, Boris, Hoffmann, Mignon, Don Giovanni, Faust, Pelléas, and on the same evening sang both Gianni Schicchi and Chim-Fen in L'Oracolo; and the team of Rosa Raisa and Giacomo Rimini appeared separately -- but more often together -- in Norma, Aïda, Fanciulla del West, Francesca da Rimini (!), Falstaff, Andrea Chenier, Isabeau, I Gioelli della Madonna, Tosca, and La Juive.

It should be apparent after reading through all these items that the first two decades of resident opera in Chicago were such as to stagger the mind when viewed a helf-century later. And although there was a generous helping of the works of Massenet, if he seems absent from the preceding list, that is because the chart tells it all. Fit the notations of the chart into the list above, and the seasons become amazingly daring and yet balanced in a way that no company can boast in the current day and age. Needless to say, the list above is nowhere near complete, but simply jottings of the highlights that leaped off the pages at me while going over the annals. One other note should be mentioned and that is the annals refer only to the performances by the resident company in Chicago. These companies did tour to various cities -- including many trips to New York -- and the performances were usually well-received by the press and the public. For a few years there was a special connection with Philadelphia, and indeed the company was know for a time as the Chicago-Philadelphia Grand Opera Company... or if you lived on the east coast, the Philadelphia-Chicago Grand Opera Company! In any event, perhaps the City of Brotherly Love had the very best of it, what with productions from Chicago and the regular tours from the Met...

* *

* * *

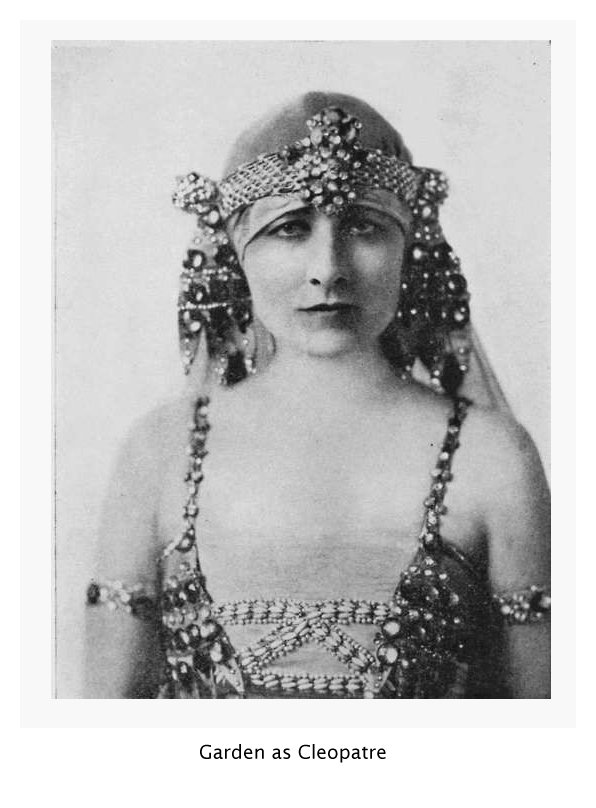

Getting back to Mary Garden, in those days she sang practically nothing but modern operas -- many of them world premieres. But consider what they were: Pelléas et Mélisande, Louise, Salome, L'Amore dei Tre Re, and of course the works of Massenet, as well as Monna Vanna (Février), Aphrodite (Erlanger), and Camille (Hamilton Forrest) to mention just a few. Naturally she did sing some older operas -- including Carmen and Faust -- but her dramatic flair and natural flamboyance made these new works come alive. One prominent banker remarked in 1920, "I only go to the opera when Mary's there because, you know (ha! ha!) she really is good to gaze upon." Her Salome was both a scandal and a sensation, but she herself later remarked, "The Chicago audiences seem to prefer me in Thaïs because I wear fewer clothes in that one." Cléopâtre drew this notice, "After many years of study and thought, I have learned why they give grand opera in foreign languages. It is so that they may present Massenet's Cléopâtre... without danger of police interference. I won't dwell on the details in the columns of a newspaper intended for general circulation... Compared to it, her Salome of a few years ago was a demure and inexperienced young flapper." The critic went on, "It has the most appalling score that was ever perpetrated. Mary Garden's voice could neither help nor harm it."

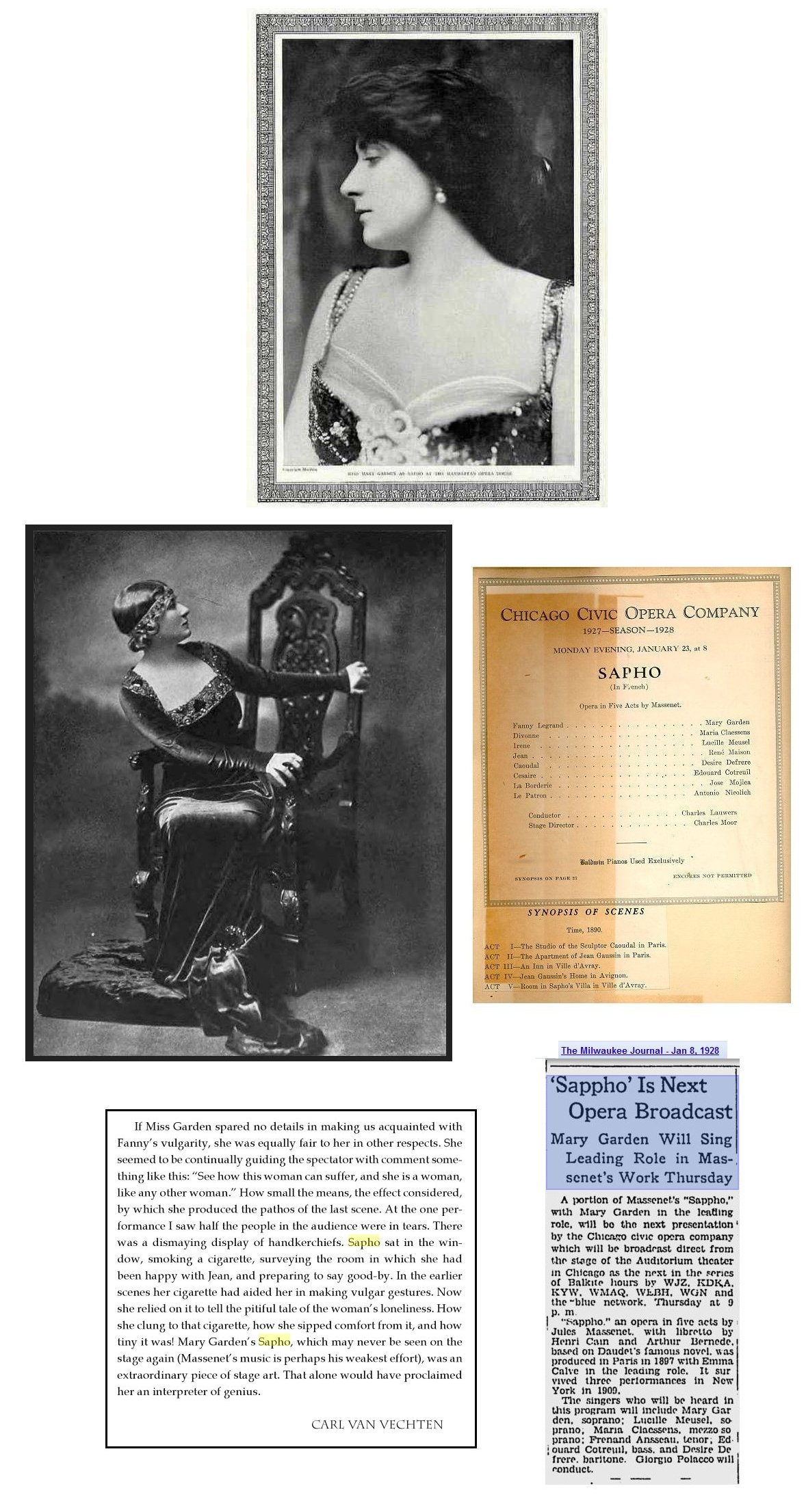

There were others, though. Sapho was dramatically good for Garden. One critic wrote, "The music seemed scarcely more than an irritation." The opera was staged carefully, particularly the orgy in the first act. "Garden flashed in gorgeous red hues, bare legged in the first act and bare armed in the second. She came close to making the hit of her Chicago career with it." In Montemezzi's L'Amore dei Tre Re, she spent the last twenty minutes of the opera with her head hanging over the end of a bench playing dead. She always was there herself - never utilizing an understudy for the scene. Operatic wags got to speculating at parties about what she was thinking during that time... The opera was done in the first season of the new house (1929-30) and a critic said, "There was such a love scene that would cause hesitation in the mind of any right-minded movie censor."

All of this freedom of expression was not confined to the stage. The Tribune said of Garden that she is "as difficult of classification as a French verb." In 1929 she wanted to talk to the press about the freedom of the modern woman and love. "Contemporary women and especially American woman" she said, "were too calculating to love completely. Women do not live for love; they work for their living. They do not inspire men and they do not care whether they do or not. Still, women are not wholly free. Perhaps in fifty years they may be." Garden continued, "I don't like the past. It's fine that women no longer love as they did, but it will be finer if they can win absolute freedom. Formerly we were under the man's heel. Now just his little toe is on us. Yet how conscious we are of that little toe."

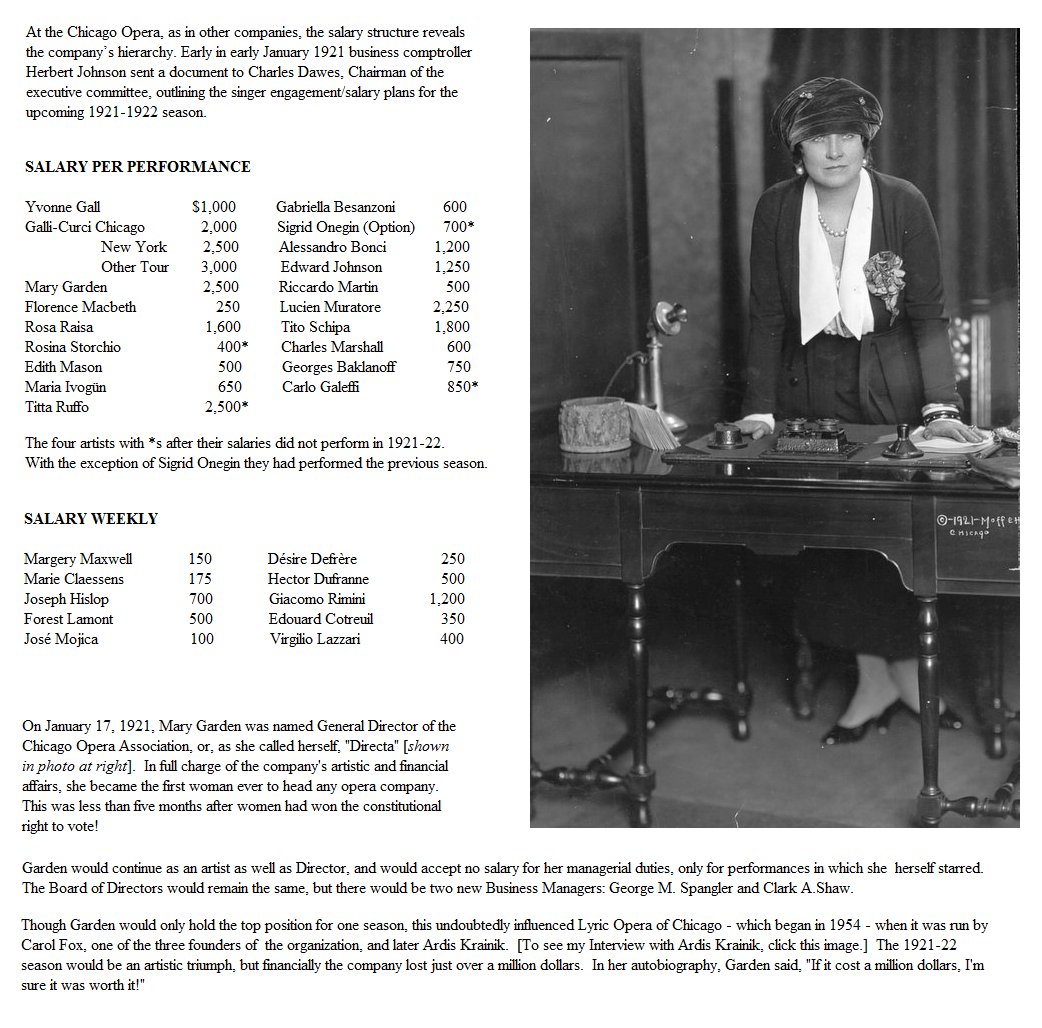

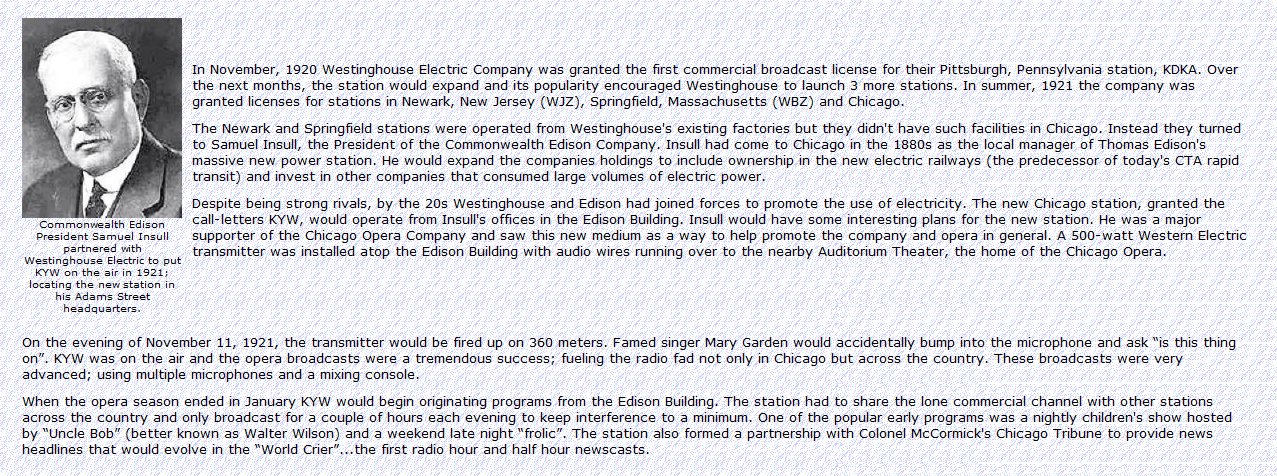

There is one further aspect of the artistry of Mary Garden that cannot be

left out. In 1921, Harold McCormick was about to end his association

with the opera company. He's been the financial mainstay for over a

decade, and the company was doing rather nicely. Attendance was down

a bit during the previous year, though, and he wanted to go out with a blaze

of glory. To do this, he needed something extra spectacular to induce

the public to return, and he approached Garden with the idea of naming her

the Director of the company. The idea had been considered by the Board

of Directors before, but this time McCormick was quite determined.

She finally accepted his offer, but with several things understood.

First, she was to have a completely free hand to choose casts and administrators;

second, she would take the post for just one season, but no one was to know

that fact lest she lose any trace of discipline; and third, she would not

be paid for the position, but only draw a salary for the performances she

sang. McCormick agreed to back her in every way -- including financially

-- and so in January of 1921, it was announced that Mary Garden would be

the General Director (or "Directa" as she liked to be called) of the Chicago

Civic Opera Association. She was the first woman ever to head an opera

company, and remember that this was less than five months after women got

the constitutional right to vote in this country!

There is one further aspect of the artistry of Mary Garden that cannot be

left out. In 1921, Harold McCormick was about to end his association

with the opera company. He's been the financial mainstay for over a

decade, and the company was doing rather nicely. Attendance was down

a bit during the previous year, though, and he wanted to go out with a blaze

of glory. To do this, he needed something extra spectacular to induce

the public to return, and he approached Garden with the idea of naming her

the Director of the company. The idea had been considered by the Board

of Directors before, but this time McCormick was quite determined.

She finally accepted his offer, but with several things understood.

First, she was to have a completely free hand to choose casts and administrators;

second, she would take the post for just one season, but no one was to know

that fact lest she lose any trace of discipline; and third, she would not

be paid for the position, but only draw a salary for the performances she

sang. McCormick agreed to back her in every way -- including financially

-- and so in January of 1921, it was announced that Mary Garden would be

the General Director (or "Directa" as she liked to be called) of the Chicago

Civic Opera Association. She was the first woman ever to head an opera

company, and remember that this was less than five months after women got

the constitutional right to vote in this country!The announcement was made the day before she was to sing a performance, so the reporters were kept away. But during the intermission that next day, she held a press conference in her dressing room. She told the world that she was delighted with the prospect and had been given virtually a blank check to run the company the way she saw fit. She was determined to make this an American opera company both onstage and in the offices, and she wanted to make it the very best opera company in the world. And she intended to impose discipline on the artists to achieve those goals.

That summer, Garden went to Europe hiring singers for the company. It must be remembered that decisions about repertoire and casting back then were not made years in advance as they are today, but rather almost on the spot from week to week. In the end, she wound up hiring many more singers than she could possibly use, with the result that during the season many world-class singers were hardly used or were completely idle. A few, after complaining about not working, were simply paid the amount in their contract and told their services were not needed. On balance, however, many singers commented that the amount of rehearsals provided time for comfort in their roles and with their colleagues.

And what a season it was! In addition to the Massenet works, Prokofiev conducted the premiere of his Love for Three Oranges; Muratore sang Samson, Faust, Roméo, Herod, Monna Vanna, L'Amore dei Tre Re and Pagliacci; Galli-Curci was Lucia, Violetta, Rosina, Gilda, Butterfly, Juliette, and Lakmé; Baklanoff sang Méfistofélès, Sharpless, Louise, Tosca, Lakmé, and L'Amore dei Tre Re; Schipa was the Duke, Edgardo, Almaviva, and Gerald; Raisa was Tosca and Elizabeth in Tannhäuser, while Rimini was in Bohème, Rigoletto, Lucia, and Butterfly, and together they were in Aïda, Otello, I Gioelli della Madonna, and Fanciulla del West. Edward Johnson sang Pinkerton, and Garden herself was Salome, Monna Vanna, Carmen, Mélisande, and in L'Amore dei Tre Re along with her Massenet roles of Jongleur and Thaïs. It was reported later that the company lost just over $1 million that season, but McCormick paid it with good humor and Garden stated flatly that it was worth it.

* *

* * *

The era of prohibition was an exciting one -- at least from the vantage point of the 1980s. Thanks to Al Capone, Chicago was notorious for gangsters and violence. Much of it was real, and sadly an everyday occurrence. During her year as General Director, Mary Garden found many interesting items in her mail, including threats of violence and even death. She was the recipient of a few knives and a couple of revolvers, and one time a box of bullets. The box had one of the bullets removed and the note explained that the missing one was meant for her. McCormick insisted that Garden have a bodyguard, but she managed to go about her business without too much inconvenience.

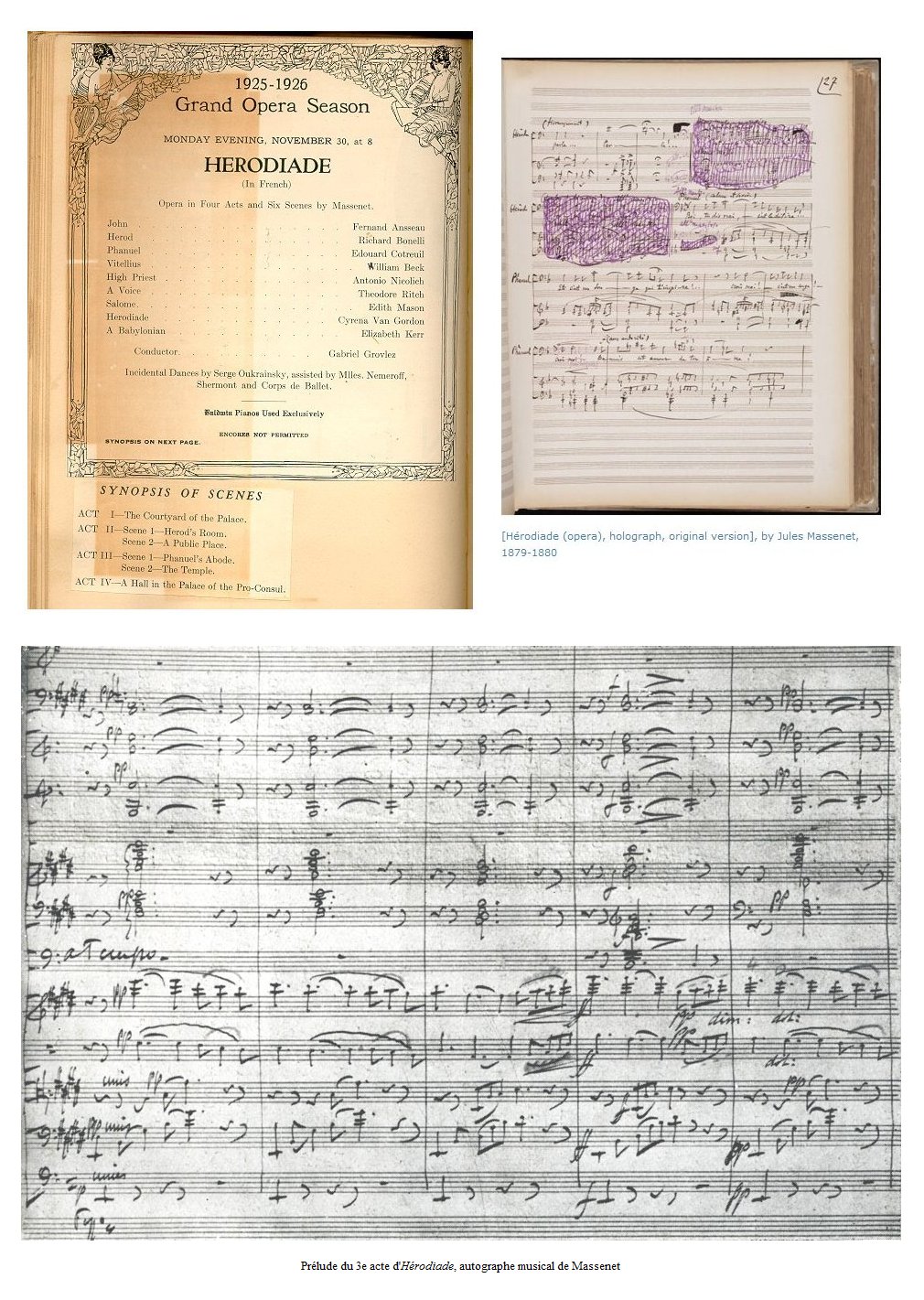

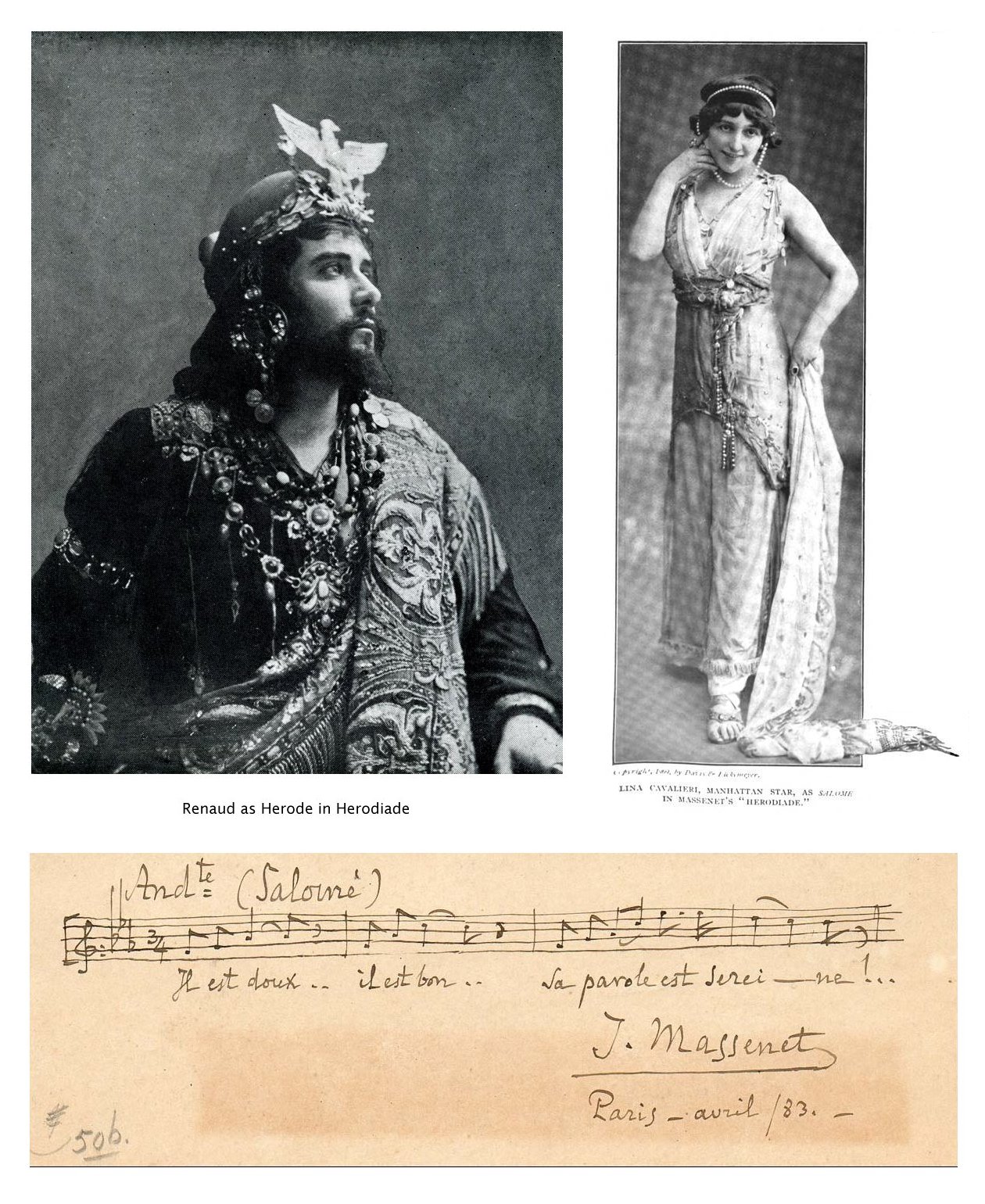

In 1925, a bootlegger was shot while getting a haircut at the barber shop. The press made much of the fact that in his coat pocket were four tickets to that evening's opera performance. That same year, a performance of Hérodiade was delayed when the baritone, William Beck, failed to show up. He was later found dead in his hotel room. The official verdict was that he died of a stroke, but the rumor had it that he'd been poisoned by a gift of some wine. The bottle was taken to police headquarters for examination, but the contents disappeared before the chemical analysis could be done.

| [Translation of a foreign-language

(Hungarian) newspaper archived at the Newberry Library, Chicago] The Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey was published in 1942 by the Chicago Public Library Omnibus Project of the Works Projects Administration of Illinois. The purpose of the project was to translate and classify selected news articles that appeared in the foreign language press from 1855 to 1938. The project consists of 120,000 typewritten pages translated from newspapers of 22 different foreign language communities of Chicago.  Otthon -- December 06, 1925

Otthon -- December 06, 1925William Beck, Hungarian Opera Singer Found Dead The news of the death of William Beck caused great consternation in Chicago and especially among the Hungarians. Everyone loved Beck, who has been with the Chicago Opera for the last fourteen years. Everyone was surprised to hear of his sudden death, because he had not been ill and sang his part in "Madame Butterfly" perfectly Sunday. Monday evening he was to sing the part of Vitellius in "Herodiade." When the performance started and Beck didn't appear, the manager sent the call-boy for him to his hotel. In the meantime, Desire Defrere, also a baritone, took his place on the stage. The call-boy went to Beck's room at the Auditorium Hotel, knocked on the door and received no answer. He tried to open the door and succeeded, because it wasn't locked. The singer was lying on his bed motionless. The boy thought he was just ill and called the house physician, who pronounced Beck dead, probable cause, heart failure. As Beck was a bachelor,with no known relatives, the Opera Company wanted to bury him. At this time Benjamin Ehrlich, an attorney, appeared, saying that he was Beck's best friend and he demanded that an inquest be made to find out whether Beck wasn't poisoned. Ehrlich said that the night before his death, Beck drank some wine at a party and complained soon after of illness. The funeral was postponed until Dec. 27. William Beck was fifty years old. He knew every opera ever written. Although he has no relatives in America, a million people mourn his death. |

And the claque made its presence felt. Singers were threatened with violence if they did not hire certain applauders. A notice appeared backstage which stated, "Ignore cajolery, but if direct threats are made to you, please inform the management." Chicago's widely-known reputation continues in some part even today. A recent [1974] television special about one of the triumphant tours of the Chicago Symphony with Sir Georg Solti was entitled, "Real Violins in their Cases."

But to get back once again to Mary Garden... She continued to sing with the company until 1931. It happened that Jongleur was her last appearance in Chicago, and it closed the 1930-31 season. She later said that during the opera, while others were singing, she sat by herself in one corner of the stage, and before she realized it she was talking to herself, or rather to the little boy she was playing. "Dear little Jongleur," she said, "you've performed all your little stunts. Everything you had you've given to the Virgin. Now your work is done." Then, turning to herself, she thought, "I, Mary Garden, have given twenty of the best years of my life to my work here in Chicago, and I've given everything to the people as well as I could, and now I think I'll go." When the curtain fell, she went to her dressing room, gathered her things together, returned to her hotel, and without saying good-bye to anyone, left the city. When she got back to Paris, she cabled the manager of the company, "My career in America is over."

During those twenty years, her name became virtually synonymous with the Chicago Opera, and her departure seemed to foreshadow the dark days ahead. With her, she took the great golden era of opera in Chicago. Garden caused more excitement on the operatic scene in Chicago -- both onstage and off -- than any other personality in the company's history. Her career began and ended in controversy, and she was never very long out of the newspapers. James Gibbons Huneker once called her, "A condor, an eagle, a peacock, a nightingale, a panther, a society dame, a gallery of moving pictures, a siren, an indomitable fighter, a human woman with a heart as big as a house, a lover of sport, a canny Scotch lassie -- a superwoman, that is Mary Garden."

* *

* * *

A few notes should be made regarding the chart of Massenet operas done in Chicago from 1910-1932. The reason for the seasons included and excluded have been mentioned before. It was also noted that there was no opera in 1914-15. The only season with no operas of Massenet was 1926-27. Two of his operas are short enough to allow something else on the evening's bill: Jongleur and Navarraise. Jongleur was done in twelve seasons, and in five of them there was nothing else at that performance. In three seasons the evening was filled out with a ballet after the opera. In the first two seasons, the opera was paired with Il Segreto di Suzanne (with Sammarco and White) and once with A Lover's Quarrel (with Sammarco and Zeppilli). Suzanne, incidentally, was also paired with a couple of other short works in the 1912 season. In 1917-18, Jongleur was done with The Daughter of the Forest by Nevin, and in its final appearance in 1930-31, the two short Massenet operas were done together with Garden appearing in both. The only other season with Navarraise (1915-16) had it paired with Pagliacci. That season, by the way, was the only one in which Mary Garden did not appear in Chicago.

It should also be noted that there are sometimes changes in casting from performance to performance, and these are mostly now reflected in the chart. [This was not done in the original published version.] Some of the names are completely unfamiliar to most people these days, but the biographies and photos which are now included on this webpage should help to introduce everyone to these forgotten artists, and bring the entire company -- or at least the French wing -- back together in this new, electronic way. One further note. There were several Gala Evenings during those years when scenes or acts of operas were given. Massenet's scores were represented in approximately the same proportion in which they were done in the rest of the season, which means a goodly helping. These have not been noted in the chart, however.

As I mentioned at the beginning, the task of compiling and sorting these operas was both immensely rewarding and excruciatingly frustrating. I hope that those who read this will enjoy what I have found, and will tingle just a bit at the glorious echoes which, some scientists say, will rustle around the universe forever.

Operas of Massenet done by Resident Companies

in Chicago 1910-1932

(with a prologue showing the beginnings of the company in New York)

(with a prologue showing the beginnings of the company in New York)

| ///////////// |

Thaïs |

Jongleur |

Cendrillon |

Hérodiade |

Don Quichotte |

Manon |

Werther |

Navarraise |

Cléopâtre |

Grisélidis |

Sapho |

| Cast of characters in the opera |

Thaïs Athanaël Nicias Paalemon |

(Other work - if any) Jean Boniface Prior Monk Poet Monk Painter Monk Sculptor Monk Musician |

Cendrillon Prince Pandolphe King Mme. Haltiere Pleasure Supt. Prime Minister |

Hérodiade

Hérode Salomé Jean Vitellius Phanuel High Priest |

Don Quichotte Sancho Dulcinée |

Manon

Des Grieux Lescaut Comte Guillot De Brétigny |

Charlotte

Werther Albert Sophia Bailiff |

(Other work - if any) Anita Araguil Garrido Ramon Bustamente Remigio |

Cléopâtre

Spakos Ennius Marc Antoine |

Grisélidis

Alain Marquis Devil Gondebaud Bertrade |

Fanny Jean Caoudal Divonne Cesaire |

| Oscar Hammerstein's

Manhattan Opera Company |

|||||||||||

| 1906-07 |

Note:

There was no doubling of roles in Jongleur.

Some singers would, however, sing various roles in separate performances. |

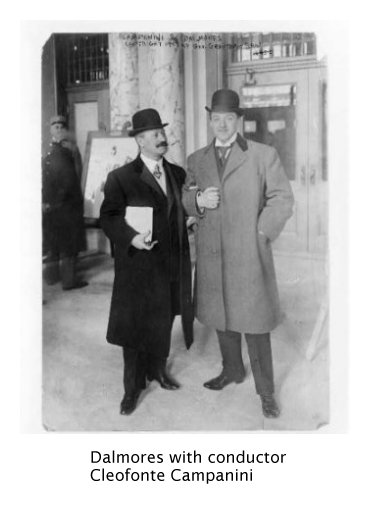

During the seasons 1906-09, all of the performances with Garden,

as well as most of the other French repertoire (including Navarraise), were conducted by Cleofonte Campanini. During the final season of 1909-10, the conductor for all of these operas was Henriquez De la Fuente. |

(w/Pagliacci) Calvé Dalmorès Arimondi Altchevsky Gilbert Seveilhac/Gianoli-Galletti |

||||||||

| 1907-08 |

Garden Renaud Dalmorès Mugnoz |

Garden also sang Louise and Pelléas et Mélisande |

(w/Pagliacci) Gerville-Réache Dalmorès Arimondi Crabbé Gianoli-Galletti ? |

||||||||

| 1908-09 |

Garden Renaud [Cazauran]/Dalmorès/Vallès Vieuille/DeGrazia |

(alone) Garden Renaud Dufranne Vallès De Segurola Vieuille Crabbé |

Garden also sang Louise, Salome, and Pelléas et Mélisande. At one performance of Thaïs, Misha Elman played the Meditation with the orchestra. |

(w/Pagliacci) Gerville-Réache Vallès Dufranne Crabbé Gianoli-Galletti Vieuille |

|||||||

| 1909-10 |

Garden Renaud Vallès/Dalmorès/Lucas Scott |

(alone) Garden/Devriès (tenor) Renaud/Gilbert/Dufranne Dufranne/Huberdeau Lucas Laskin/Scott Huberdeau/Scott Crabbé/Scott |

Gerville-Réache/Doria/D'Alvarez Renaud Cavalieri/Mazarin Dalmorès/Duffault/Lucas Crabbé/Dufour Vallier Nicolay |

Garden also sang Faust, Salome, and Pelléas et Mélisande, and organized a benefit concert for Paris Flood sufferers, singing scenes from Roméo et Juliette, Thaïs and Manon. |

(w/Pagliacci) Gerville-Réache Dalmorès/Devriès Dufranne Crabbé Nicolay Huberdeau |

Garden Dalmorès Dufranne Scott Huberdeau Duchène |

Garden Dalmorès Dufranne D'Alvarez/Soyer Leroux |

||||

| The company moves to

the Windy City and becomes the Chicago Grand Opera Company |

|||||||||||

| 1910-11 |

Garden Renaud/Dufranne Dalmorès/Warnery Huberdeau/Nicolay |

Garden also sang Pelléas

et Mélisande, Salome, Louise, and Faust. From 1910-1917, all Massenet operas were conducted by Campanini, except as noted. |

Note: The Chicago reference being used for this section of the chart often lists fewer characters than the Manhattan reference used above. |

||||||||

| 1911-12 |

Garden Dufranne Dalmores/Warnery Huberdeau/Nicolay |

(w/Segreto) Garden Dufranne Huberdeau Warnery Scott Preisch/Nicolay Crabbé |

Teyte/Zeppilli Garden Dufranne Scott Berat Defrère Nicolay |

Garden also sang Carmen and Natoma by Victor Herbert. |

|||||||

| 1912-13 |

Garden Dufranne Warnery Huberdeau |

(w/Segreto) Garden Dufranne Huberdeau Warnery Scott Nicolay Crabbé |

Teyte/Zeppilli Darch/Stanley Dufranne/Warnery Huberdeau/Scott Berat Defrère Nicolay |

de Cisneros Dalmorès White Mascal Huberdeau [Phanuel] |

Garden also sang Louise,

Carmen, and Tosca - which she sang in French (except

forthe aria Vissi d'arte) while

the rest of the cast sang in Italian! Marcel Charlier conducted Cendrillon and Hérodiade. |

||||||

| 1913-14 |

Garden Ruffo/Dufranne Dalmores/Warnery Huberdeau |

(alone) Garden Dufranne Huberdeau |

Claussen Dalmorès White Crabbé Huberdeau [Phanuel] |

Vanni-Marcoux Dufranne Garden |

Garden Muratore Dufranne Huberdeau |

Garden also sang Louise, Tosca, and Monna Vanna. Charlier conducted Manon. |

|||||

| 1914-15 |

No

season, after which the company is re-formed and named the Chicago Opera

Association |

||||||||||

|

1915-16 |

Kuznietsov Dufranne Dalmores Nicolay |

Because the re-organization of the resident opera company was so late, Garden was unable to accept any Chicago engagements during this season. Charlier conducted Navarraise; Rodolfo Ferrari led Werther. |

Supervia Muratore Dufranne Sharlow Nicolay |

(w/Pagliacci) Claussen Dalmores Arimondi |

Kuznietsov Dalmores Journet Maguenat |

||||||

| 1916-17 |

Garden Dufranne Dalmores Nicolay |

(alone) Garden Dufranne Journet |

Claessens Dalmorès Amsden Beck Journet Nicolay |

Amsden Muratore Maguenat Journet |

Garden also sang Carmen, and Louise. Charlier conduced Hérodiade and Manon. |

Garden ? Dufranne Journet Maguenat Berat |

|||||

| 1917-18 |

Garden Dufranne Dalmores Huberdeau |

(w/A Daughter of the Forest) Vix Dufranne Huberdeau |

Garden was delayed in Paris until the last three weeks of the season, so Geneviève Vix took over most of her French roles. Besides Thaïs, Garden sang Carmen, Monna Vanna, and Pelléas et Mélisande. |

Vix Muratore Maguenat Huberdeau Dua Defrère |

From 1917-1920, all Massenet operas

were conducted by Charlier unless otherwise noted. |

Vix Dalmores Dufranne Berat |

|||||

| 1918-19 |

Gall Journet Lamont Huberdeau |

Garden also sang Monna Vanna and Gismonda, both by Henry Février, and Carmen. Louis Hasselmans conducted Thaïs, Werther, and Manon. |

Gall Fontaine Maguenat Huberdeau Dua Defrère |

Pavloska Muratore/O'Sullivan Maguenat Sharlow Huberdeau |

Garden Fontaine Journet Maguenat |

||||||

| 1919-20 |

Garden Baklanoff Fontaine Huberdeau |

(alone) Garden Dufranne Huberdeau |

D'Alvarez O'Sullivan/Fontaine Gall Maguenat Defrère Cotreuil |

Gall Schipa Maguenat Huberdeau Warnery Defrère |

Garden also sang Carmen, Pelléas et Mélisand, Monna Vanna, L'Amore dei Tre Re, and Louise. |

Garden Fontaine Huberdeau Maguenat |

Hasselmans conducted Thaïs. Gino Marinuzzi led Manon. |

||||

| 1920-21 |

Garden sang Aphrodite by Camille Erlanger, Monna Vanna, Carmen, Faust, and L'Amore dei Tre Re. Henri Morin conducted Manon. |

Gall Muratore Dufranne Cotreuil Defrère Nicolay |

|||||||||

| The Company is re-named the Chicago Civic Opera |

|||||||||||

1921-22 |

Namara/Garden Dufranne/Cotreuil Martin Nicolay |

(w/ballet) Garden Dufranne Payan |

Garden also sang Monna Vanna,

Carmen, Salome, L'Amore dei Tre Re, Pelléas et Mélisande, and Louise. From 1921-30, all Massenet operas were conducted by Giorgio Polacco unless otherwise noted. Gabriel Grovlez conducted Manon and Thaïs. |

Mason Muratore Maguenat Payan Dua Defrère |

During this season, Garden ran the company as the General Director, or as she called it, "Directa," as well as singing various roles. |

||||||

| 1922-23 |

Garden sang Carmen, L'Amore dei Tre Re, and Tosca. Richard Hageman conducted Manon. |

Galli-Curci Schipa Defrère Cotreuil Mojica Beck |

|||||||||

| 1923-24 |

Garden Cotreuil Mojica Kipnis |

(alone) Garden Cotreuil Kipnis Mojica Beck Lazzari Defrère |

Garden also sang Louise, and Carmen. Ettore Panizza conducted Manon, Cléopâtre, and Thaïs |

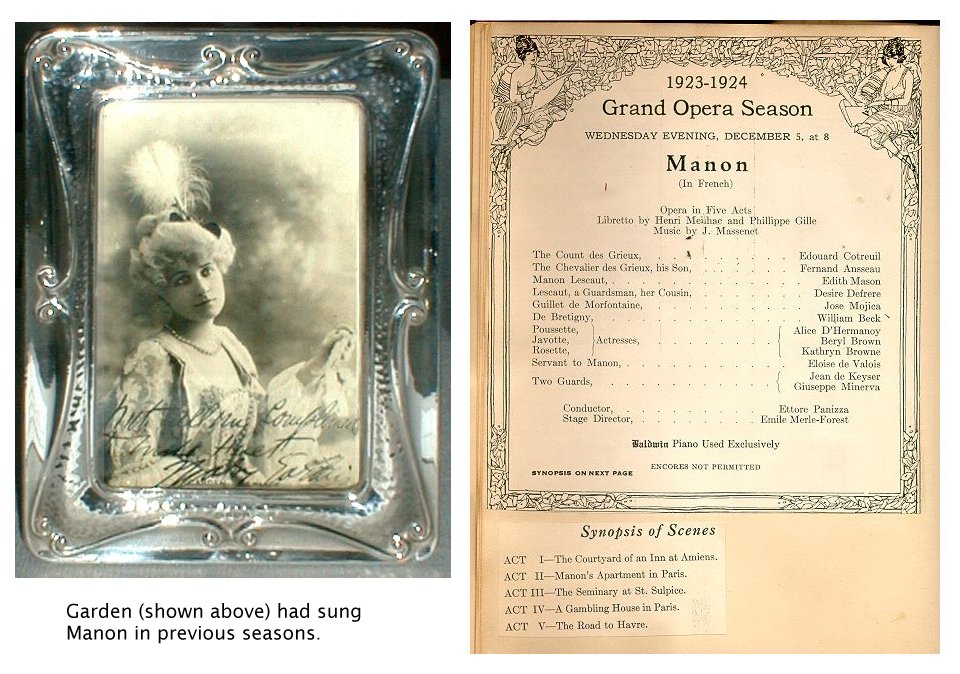

Mason Ansseau Defrère Cotreuil Mojica Beck |

Garden Defrère Cotreuil Baklanoff |

||||||

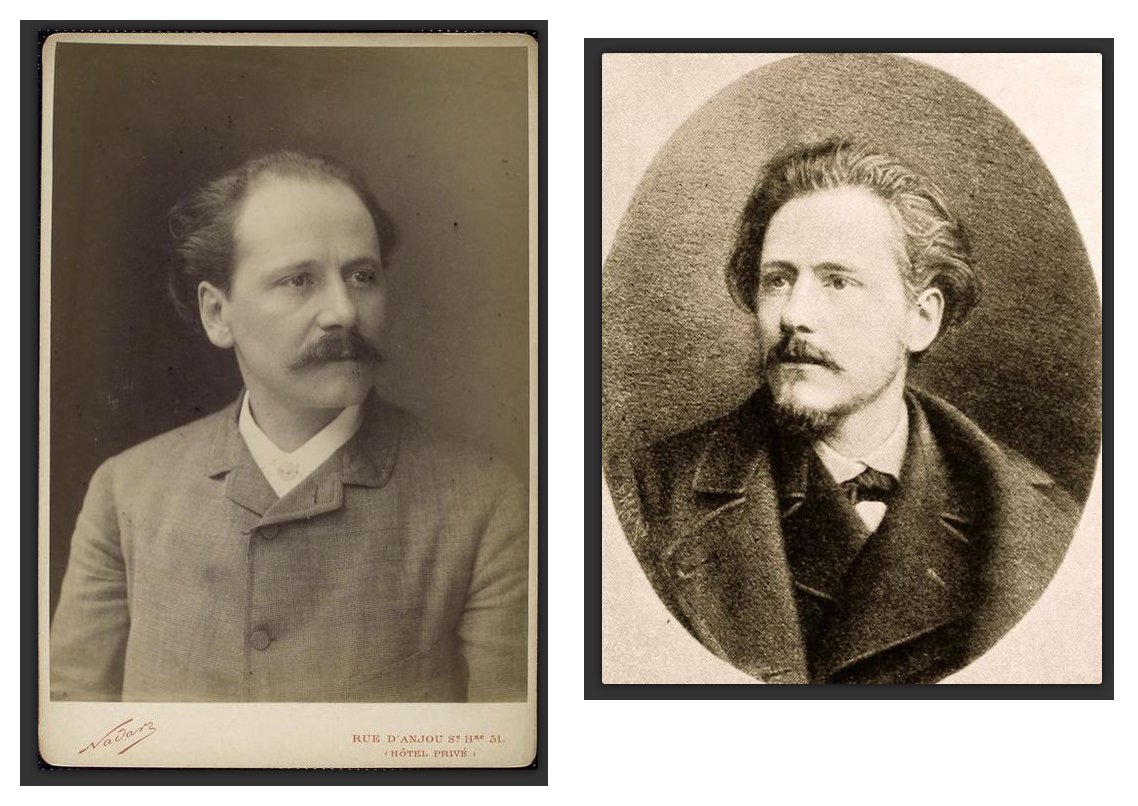

| 1924-25 |

Garden Schwarz/Cotreuil Mojica Kipnis/Nicolich Swarthout as Myrtale |

(alone) Garden Cotreuil Kipnis Mojica Beck Nicolich Defrère |

Garden also sang Carmen, L'Amore dei Tre Re, Louise, and Pelléas et Mélisande. Roberto Moranzoni conducted Thaïs. |

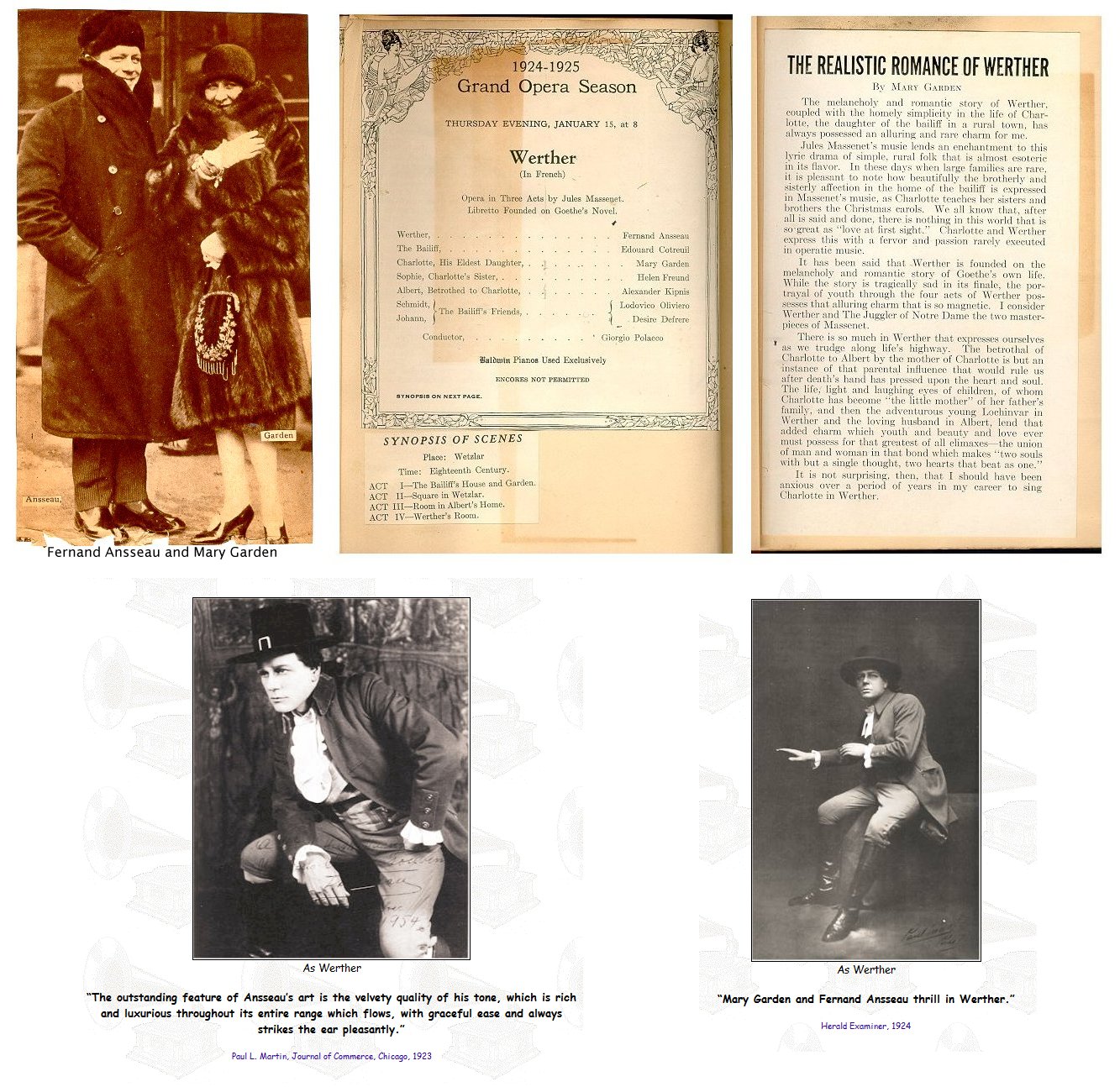

Garden Ansseau Kipnis Freund Cotreuil |

|||||||

| 1925-26 |

Van Gordon Ansseau Mason Bonelli Beck Cotreuil Nicolich |

Garden Ansseau Kipnis Freund Cotreuil |

Garden also sang Pelléas et Mélisande, Carmen, Louise, and Resurrection by Franco Alfano. Gabriel Grovlez conducted Hérodiade. |

||||||||

| 1926-27 | (No Massenet operas were done this season) [Garden sang Resurrection, Carmen, L'Amore dei Tre Re, Tosca, and Judith by Arthur Honegger.] | ||||||||||

| 1927-28 |

(w/ballet) Garden Formichi Cotreuil |

Garden also sang Monna Vanna, Carmen, Louise, and Resurrection. Both Polacco and Lauwers conducted performances of Sapho in this season and the next. |

Garden Ansseau/Maison Defrère Claessens Cotreuil |

||||||||

| 1928-29 |

Garden Formichi Mojica Nicolich |

Garden also sang L'Amore dei

Tre Re, Pelléas et Mélisande, and Judith. Moranzoni conducted Thaïs. |

Garden Maison ? Claessens |

||||||||

| 1929-30 |

Garden Vanni-Marcoux/Formichi Mojica Nicolich |

(w/ballet) Garden Formichi Cotreuil Ritch Ringling Nicolich Defrère |

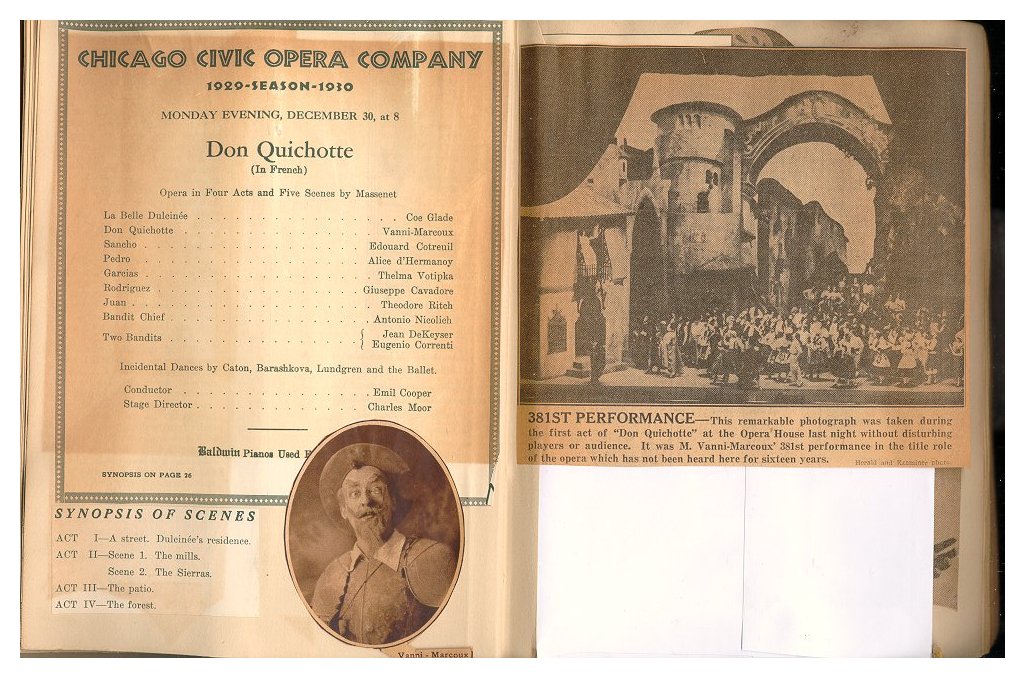

Vanni-Marcoux Cotreuil Glade |

Garden also sang L'Amore dei Tre Re, Louise, and Pelléas et Mélisande. Moranzoni conducted Thaïs. Emil Cooper conducted Don Quichotte. |

|||||||

| 1930-31 |

(w/Navaraise) Garden Formichi Baromeo |

Garden also sang Resurrection,

Pelléas et Mélisande, and Camille by Hamilton Forrest. Charles Lauwers conducted Jongleur. Cooper conducted all the rest of the Massenet operas this season and the next. |

McCormic Hackett Vieulle Coutreuil Dua Defrère/Ringling |

(w/Jongleur) Garden Maison Ritch ? Cotreuil |

A performance of Jongleur (w/ballet) closed the season, and ended Mary Garden's career in Chicago. |

||||||

1931-32 |

Olszewska Maison McCormic Thomas Defrère Baromeo Benoni |

||||||||||

|

Epilogue There was no season in 1932-33. The company was reconstituted as the Chicago Grand Opera Company (again) for 1933-35, with significantly shorter seasons - just a few weeks in the fall starting in 1934. The company was called the Chicago City Opera from 1936-39, and the Chicago Opera Company from 1940-46, with no season in 1943. 1947-53 was the "dark period" before the Lyric Theater was formed in 1954. After a couple of years it was re-named Lyric Opera which enjoys a long and continuous chapter of opera in the Windy City. Between 1933 and 1947, the only two Massenet operas done were Manon and Thaïs. A single performance of Manon in 1933-34 had Marion Claire, Dino Borgioli and Desiré Defrère. The conductor, Henry Weber, was married to Claire, the third instance of a long-time Chicago opera conductor wedded to a significant soprano! [Previous pairs were Cleofonte Campanini & Luisa Tetrazzini, and Giorgio Polacco & Edith Mason.] Helen Jepson sang both Massenet operas, as well as two other Garden specialties -- Louise and L'Amore dei Tre Re -- in various seasons between 1935 and 1942. Thaïs of 1935, 1936 and 1937 also featured John Charles Thomas as Athanaël, and Martin as Nicias. Hageman and Hasselmans conducted. The Manon of 1940 featured Dorothy Kirsten as Pousette! Grace Moore also sang Manon and L'Amore dei Tre Re in the years 1937-39, and Elen Dosia also sang Manon in those three seasons. Maria Jeritza was Salome in 1934, and Marjorie Lawrence sang the role in 1940, Bidú Sayão was Mélisande and Manon in 1944 and 1945 respectively. There were a few other French works scattered in these seasons, but nothing like the period in the chart above. |

|||||||||||

Performances on Tour 1907-29

(Casts and conductors were very much the same as in Manhattan and Chicago)

(Casts and conductors were very much the same as in Manhattan and Chicago)

| ///////////// |

Thaïs |

Jongleur |

Cendrillon |

Hérodiade |

Don Quichotte |

Manon |

Werther |

Navarraise |

Cléopâtre |

Grisélidis |

Sapho |

| Oscar Hammerstein's

Manhattan Opera Company |

|||||||||||

| 1907-08 |

No Massenet operas were done on tour this season. Garden

sang Louise in Philadelphia conducted

by Campanini. |

||||||||||

| 1908-09 |

Philadelphia Boston |

Philadelphia Boston |

Garden also sang Louise,

Salome, and Pelléas et Mélisande. Campanini, Sturani, and Charlier each conducted some performances |

(w/Pagliacci) Philadelphia Boston |

|||||||

| 1909-10 |

Washington |

Philadelphia Pittsburgh Washington Boston |

Philadelphia |

Garden also sang Faust,

Louise, and Pelléas

et Mélisande, plus Act III of Roméo

et Juliette at the closing Gala. Nicosia, Sturani, De la Fuente and Charlier each conducted some performances. |

(w/.Fille du Regiment; or w/Pagliacci) Philadelphia Boston |

Philadelphia Boston |

Philadelphia Pittsburgh Cincinnati |

||||

| The company moves to

the Windy City and becomes the Chicago Grand Opera Company |

|||||||||||

| 1910-11 |

Baltimore Brooklyn Milwaukee New York City Philadelphia |

(w/Segreto) Baltimore New York City Philadelphia |

There were also performances in various cities of Carmen, Salome, Louise, Pelléas et Mélisande, and Natoma by Victor Herbert. As no cast lists are printed in the reference used, it can be assumed that the casts were the same or very similar, so Garden probably appeared in most or all of these operas. |

||||||||

| 1911-12 |

Baltimore Cleveland Philadelphia St. Louis |

(w/Segreto) New York City Philadelphia St. Paul, MN |

New

York City Philadelphia |

There were also performances of Pelléas et Mélisande, Louise, and Natoma. |

|||||||

| 1912-13 |

Butte,

MT Dallas Denver Kansas City, MO Los Angeles Minneapolis New York City Philadelphia Portland, OR San Diego, CA San Francisco Seattle Spokane, WA |

(w/Segreto or w/ Lover's Quarrel) Cincinnati Milwaukee Minneapolis Philadelphia St. Louis San Fraancisco |

Philadelphia |

There were also performances of Louise, Natoma, and Salome. |

|||||||

| 1913-14 |

Des

Moines, IA Omaha, NE Philadelphia St. Joseph, MO San Francisco Witchita, KS |

Kansas

City, MO Los Angeles |

Philadelphia San Francisco |

New York

City Philadelphia |

Philadelphia St. Paul, MN |

There were also performances of Louise, Monna Vanna, and Natoma |

|||||

| 1914-15 |

No

season, after which the company is re-formed and named the Chicago Opera

Association |

||||||||||

| 1915-17 |

There were no tours by the company during these

two seasons. |

||||||||||

| 1917-18 |

Boston New York City |

(w/Cavalleria) New York City |

There were also performances of Louise, Monna Vanna, and Pelléas et Mélisande. |

New York |

|||||||

| 1918-19 |

Detroit New York City Philadelphia Pittsburgh |

(w/ballet) New York City |

There were also performances of Monna Vanna, Carmen, and Pelléas et Mélisande. |

New York |

New York |

New

York City Philadelphia |

New York |

||||

| 1919-20 |

Boston New York City |

New

York City |

New York City |

There were also performances of Aphrodite by Camille Erlanger, Gismonda by Henry Février, Pelléas et Mélisande,

Louise, and L'Amore dei Tre Re.

|

|||||||

| 1920-21 |

New

York City San Francisco Tulsa, OK |

New York City |

There were also performances of Monna Vanna, Carmen, and L'Amore dei Tre Re. |

New York |

|||||||

| The Company is re-named the Chicago Civic Opera |

|||||||||||

1921-22 |

Dallas Helena, MT Los Angeles New York City Portland, OR St. Paul, MN San Antonio, TX |

Philadelphia |

There were also performanes of Monna Vanna, L'Amore dei Tre Re, Salome, Pelléas et Mélisande, and Louise. |

New York |

During this season, Garden ran the company as the General Director, or as she called it, "Directa." |

||||||

| 1922-23 |

No Massenet operas were done on tour this season. There

were performances of Carmen, and

L'Amore dei Tre Re. |

||||||||||

| 1923-24 |

(w/.(Maestro) Boston |

There were also performances of Louise, Salome, and Carmen. |

Chattanooga,

TN Denver Los Angeles Pittsburgh Portland, OR San Francisco Tulsa, OK Witchita, KS |

||||||||

| 1924-25 |

Baltimore Boston Chattanooga, TN Cincinnati Cleveland Memphis Pittsburgh Washington, DC |

There were also performances of Carmen, L'Amore dei Tre Re, Louise, and Pelléas et Mélisande. |

|||||||||

| 1925-26 |

Birmingham,

AL Boston Buffalo, NY Miami |

Boston |

There were also performances of Louise, Pelléas et Mélisande, Carmen, and Resurrection by Franco Alfano. |

||||||||

| 1926-27 | No Massenet operas were done this season in Chicago or on tour.

There were performances of Resurrection,

Carmen, Pelléas et Mélisande, and

Judith by Arthur Honegger. |

||||||||||

| 1927-28 |

(w/ballet) Boston |

There were also performances of Carmen, Louise, and Resurrection. |

Boston Fresno, CA Los Angeles |

||||||||

| 1928-29 |

Amarillo,

TX Boston Columbus, OH Detroit El Paso, TX Jackson, MS Los Angeles Minneapolis Nashville Oakland, CA Phoenix, AZ Sacramento, CA Tulsa, OK |

There were also performances of Judith and L'Amore dei Tre Re. |

|||||||||

| There were tours during

the final three seasons of 1929-32, but I do not currently have access to

those records. |

|||||||||||

Some programs and illustrations

of Massenet operas

mostly from the Chicago Opera during this period

(and presented here in the same order as in the chart above!)

mostly from the Chicago Opera during this period

(and presented here in the same order as in the chart above!)

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs

are of Mary Garden

in the specific opera being illustrated.

in the specific opera being illustrated.

| [Writing of Louise...] There are other

ways of singing and acting this rôle. Others have sung and acted it,

others will sing and act it, effectively. The abandoned (almost aggressive)

perversity of Miss Garden's performance has perhaps not been equalled, but

this rôle does not belong to her as completely as do Thaïs and

Mélisande; no other interpreters will satisfy any one who has seen

her in these two parts. Miss Garden made her American début in Massenet's opera, Thaïs, written, by the way, for Sybil Sanderson. The date was November 25, 1907. Previous to this time Miss Garden had never sung this opera in Paris, but she had appeared in it during a summer season at one of the French watering places. Since that night, nearly ten years ago, however, it has become the most stable feature of her répertoire. She has sung it frequently in Paris, and during the long tours undertaken by the Chicago Opera Company this sentimental tale of the Alexandrian courtesan and the hermit of the desert has startled the inhabitants of hamlets in Iowa and California. It is a very brilliant scenic show, and is utterly successful as a vehicle for the exploitation of the charms of a fragrant personality. Miss Garden has found the part grateful; her very lovely figure is particularly well suited to the allurements of Grecian drapery, and the unwinding of her charms at the close of the first act is an event calculated to stir the sluggish blood of a hardened theatre-goer, let alone that of a Nebraska farmer. The play becomes the more vivid as it is obvious that the retiary meshes with which she ensnares Athanaël are strong enough to entangle any of us. Thaïs-become-nun — Evelyn Innes should have sung this character before she became Sister Teresa — is in violent contrast to these opening scenes, but the acts in the desert, as the Alexandrian strumpet wilts before the aroused passion of the monk, are carried through with equal skill by this artist who is an adept in her means of expression and expressiveness. The opera is sentimental, theatrical, and over its falsely constructed drama—a perversion of Anatole France's psychological tale—Massenet has overlaid as banal a coverlet of music as could well be devised by an eminent composer. "The bad fairies have given him [Massenet] only one gift," writes Pierre Lalo, "...the desire to please." It cannot be said that Miss Garden allows the music to affect her interpretation. She sings some of it, particularly her part in the duet in the desert, with considerable charm and warmth of tone. I have never cared very much for her singing of the mirror air, although she is dramatically admirable at this point; on the other hand, I have found her rendering of the farewell to Eros most pathetic in its tenderness. At times she has attacked the high notes, which fall in unison with the exposure of her attractions, with brilliancy; at other times she has avoided them altogether (it must be remembered that Miss Sanderson, for whom this opera was written, had a voice like the Tour Eiffel; she sang to G above the staff). But the general tone of her interpretation has not been weakened by the weakness of the music or by her inability to sing a good deal of it. Quite the contrary. I am sure she sings the part with more steadiness of tone than Milka Ternina ever commanded for Tosca, and her performance is equally unforgettable. -- From Interpreters by Carl Van Vechten (1917)

|

| The story has often been related how

Massenet, piqued by the frequently repeated assertion that his muse was only

at his command when he depicted female frailty, determined to write an opera

in which only one woman was to appear, and she was to be both mute and a

virgin! Le Jongleur de Notre Dame,

perhaps the most poetically conceived of Massenet's lyric dramas, was the

result of this decision. Until Mr. Hammerstein made up his mind to produce

the opera, the rôle of Jean had invariably been sung by a man. Mr.

Hammerstein thought that Americans would prefer a woman in the part. He easily

enlisted the interest of Miss Garden in this scheme, and Massenet, it is

said, consented to make certain changes in the score. The taste of the experiment

was doubtful, but it was one for which there had been much precedent. Nor

is it necessary to linger on Sarah Bernhardt's assumption of the rôles

of Hamlet, Shylock, and the Duc de Reichstadt. In the "golden period of song,"

Orfeo was not the only man's part sung by a woman. Mme. Pasta frequently

appeared as Romeo in Zingarelli's opera and as Tancredi, and she also sang

Otello on one occasion when Henrietta Sontag was the Desdemona. The rôle

of Orfeo, I believe, was written originally for a castrato, and later, when

the work was refurbished for production at what was then the Paris Opéra,

Gluck allotted the rôle to a tenor. Now it is sung by a woman as invariably

as are Stephano in Roméo et Juliette

and Siebel in Faust. There is really

more excuse for the masquerade of sex in Massenet's opera. The timid, pathetic

little juggler, ridiculous in his inefficiency, is a part for which tenors,

as they exist to-day, seem manifestly unsuited. And certainly no tenor could

hope to make the appeal in the part that Mary Garden did. In the second act

she found it difficult to entirely conceal the suggestion of her sex under

the monk's robe, but the sad little figure of the first act and the adorable

juggler of the last, performing his imbecile tricks before Our Lady's altar,

were triumphant details of an artistic impersonation; on the whole, one of

Miss Garden's most moving performances. -- From Interpreters by Carl Van Vechten (1917)

|

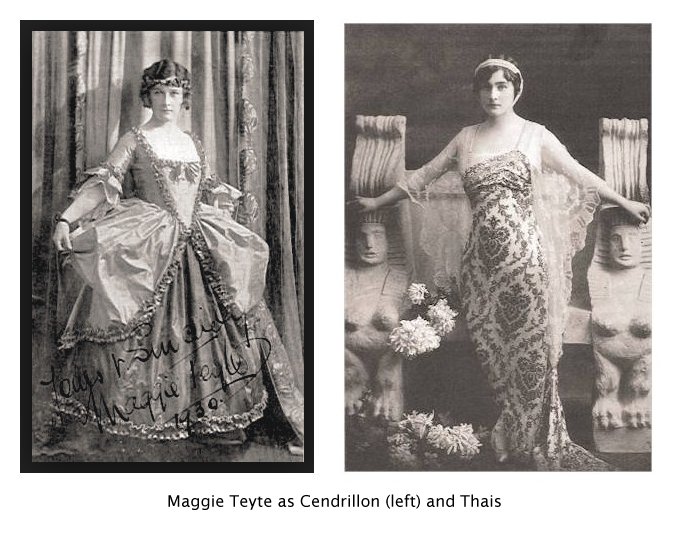

| Margaret

Tate was born in Wolverhampton, England, one of ten children of Jacob

James Tate, a successful wine and spirit merchant and proprietor of public

houses and later lodgings. Her parents were keen amateur musicians and opera

enthusiasts. She was the sister of composer James W. Tate. Her family moved

to London in 1898, where Teyte attended St. Joseph's Convent School, Snow

Hill, and later studied at the Royal School of Music. Her father died in 1903 and she went to Paris the following year to become a pupil of the celebrated tenor Jean de Reszke. She made her first public appearance in Paris in 1906 when she sang Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro and Zerlina in Don Giovanni, both conducted by Reynaldo Hahn. Her professional debut took place at the Opera House in Monte Carlo on 1 February 1907, where she performed Tyrcis in Myriame et Daphné (André Bloch's arrangement of Jacques Offenbach's Daphnis et Chloé), with Paderewski. The following week, again at the Opera House in Monte Carlo, she sang Zerlina.

Finding that her surname was generally mispronounced in France, she changed it from Tate to Teyte before joining the Opéra-Comique in Paris. After a few small parts, she was cast as Mélisande in Pelléas et Mélisande by Debussy, replacing the originator of the role, Mary Garden. To prepare, she studied with Debussy himself, and she is the only singer ever to be accompanied by Debussy on the piano with an orchestra in public. In 1910, Sir Thomas Beecham cast Teyte as Cherubino and Mélisande and also as Blonde in Die Entführung aus dem Serail for his London season. Despite her early singing successes, Teyte did not easily establish herself in the main opera houses. Instead, she moved to America and performed with the Chicago Opera Company from 1911–1914 and the Boston Opera Company from 1914–17, singing in Philadelphia and elsewhere, but not in New York, though she created the title role in Henry Kimball Hadley's opera, Bianca, at Manhattan's Park Theater in 1918. Returning to Britain in 1919, she created the rôle of Lady Mary Carlisle in André Messager's operetta, Monsieur Beaucaire, at the Prince's Theatre. She married for a second time in 1921, to Canadian millionaire Sherwin Cottingham, and went into semi-retirement until 1930, when she performed as Mélisande and played Puccini's Madama Butterfly. After difficulty in reviving her career, she ended up performing music hall and variety (24 performances a week) at the Victoria Palace in London. Finally, in 1936, her recordings of Debussy songs accompanied by Alfred Cortot attracted attention, and recordings remained an important factor in her renewed fame, as she gained a reputation in England and the United States as the leading French art song interpreter of her time. She sang at the Royal Opera House in 1936–37 in Hansel and Gretel, as Eurydice in Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice and as Butterfly in Madama Butterfly. In 1938–39 she broadcast performances of Massenet's Manon in English, in addition to Eva in Wagner's Die Meistersinger. She also appeared in operetta and musical comedy between the wars. She made her first New York appearances in 1948, including a Town Hall recital followed by performances of Pelléas at the New York City Center Opera. She continued to record and perform in opera until 1951, making her final appearance in the part of Belinda (to Kirsten Flagstad’s Dido) in Purcell's Dido and Aeneas at the Mermaid Theatre in London. Her final concert appearance was at the Royal Festival Hall on 22 April 1956, aged 68. She spent her last years teaching. She died in London in 1976, aged 88. |

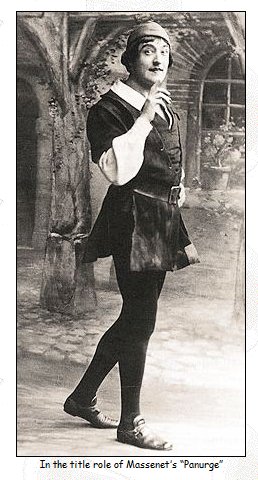

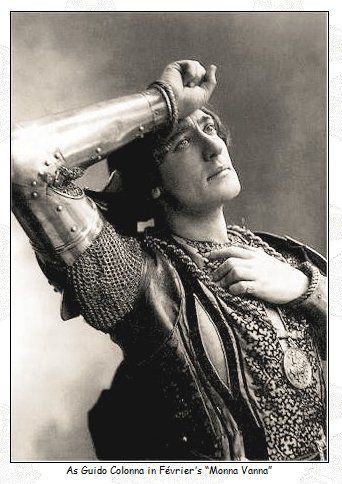

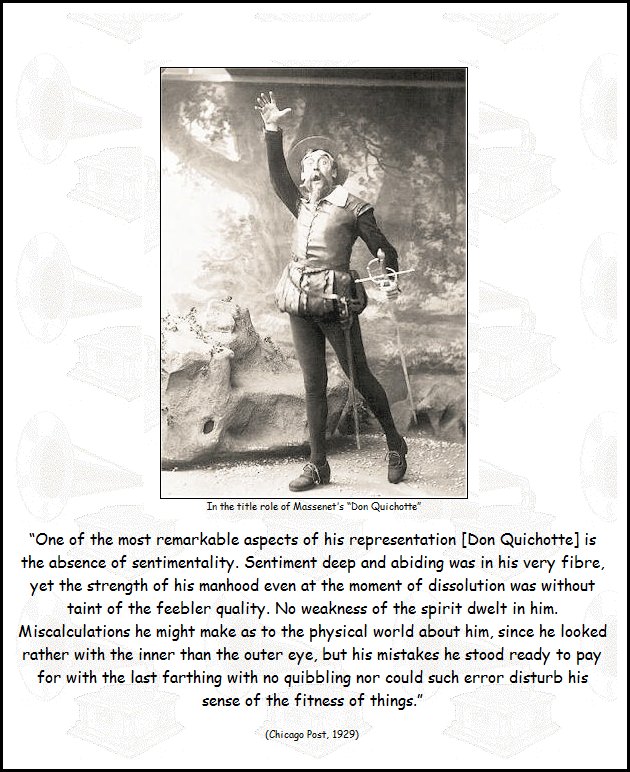

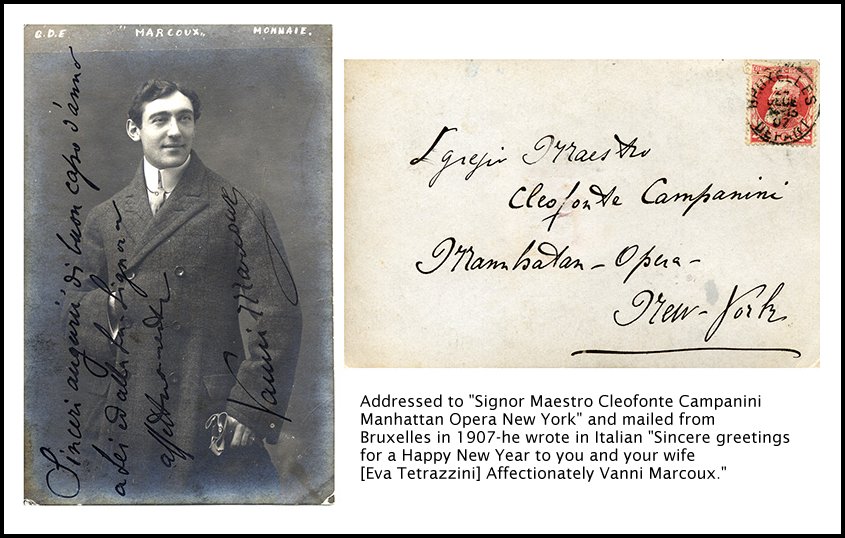

Vanni-Marcoux

was born Giovanni (Jean-Emile Diogène) Marcoux in 1877 in Turin. Vanni,

an Italian abbrevation for Giovanni, reminds us that he was the son of a French

father and an Italian mother. He studied with Collini at his hometown and

with Frédéric Boyer at the Paris Conservatoire. After successfully

completing law studies, Marcoux decided to devote himself full to singing.

His debut took place at Turin in 1894 as Sparafucile. It was not until 1899

that he made his first stage appearance in France, at Bayonne as Frère

Laurent. Thereafter he toured a number of provincial theatres and was a guest

at the La Monnaie in Brussels. In 1905 he debuted at Covent Garden as Basilio

and returned there every season until 1912, singing comprimario parts as

well as Colline and Sparafucile. Eventually he was given such parts

like Arkel, Marcel in Les Huguenots

and the Father in Charpentier’s Louise.

In 1909 he made his debut at the Opéra Paris, creating Guido Colonna

in Henri Février’s Monna Vanna,

a role which brought him fame. Three years later he appeared in the title

role of Massenet’s Don Quichotte

(probably his greatest achievement). Massenet wrote his opera Panurge especially for him. Its creation

took place in 1913. Before World War I Vanni-Marcoux was predominantly a

bass, singing even Hunding and Fafner. For nearly 40 years he was a familiar

and much admired figure in Parisian musical life, mainly at the Opéra,

but also at the Opéra-Comique, creating a number of roles in contemporary

operas such as Gunsbourg’s Lysistrata,

d’Olonne’s L’Arlequin, Février’s

Monna Vanna and La Femme nue, and Honegger-Ibert’s L’Aiglon.

Subsequently he was engaged by Henry Russell to the Boston Opera where he established as a star. His first performance was in Pelléas et Mélisande, now as Golaud. His dramatic conception of Méphistophélès in Faust was also much admired by the public. The four roles in Les Contes d’Hoffmann (Coppélius, Dr. Miracle, Crespel, Dapertutto) belonged to his greatest histrionic achievements. Without doubt, Vanni-Marcoux owed much of his success in the United States to Mary Garden. Her popularisations of the works of the modern French composers soon provided him with all sort of dramatic opportunities. There was the rumour that he had divorced his second wife in order to marry Mary Garden. She declined, but she shared the stage with him in many performances of Thaïs, Tosca, Don Quichotte, Pelléas et Mélisande and Carmen. He followed her to Chicago in 1913 and was a regular guest there between 1926 and 1931. When Mary Garden finished her career, French opera could not survive without her, and thereafter there was no place for him. La Scala saw him as Boris (in French) under Arturo Toscanini and Sigismund Zaleski in 1922. He was generally regarded as the finest exponent of the role after Chaliapin. Paris invited him to sing the title role in the first French performance of Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. From 1948 to 1951 Vanni-Marcoux was director of the Grand Théâtre at Bordeaux. He died in 1962.

|

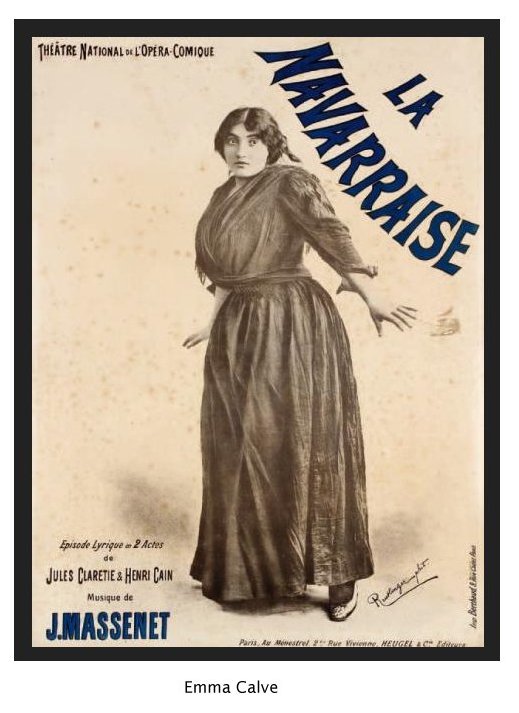

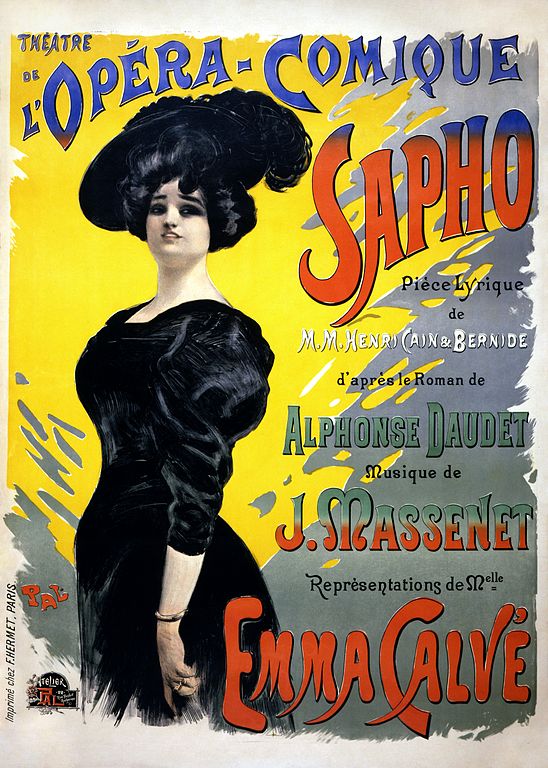

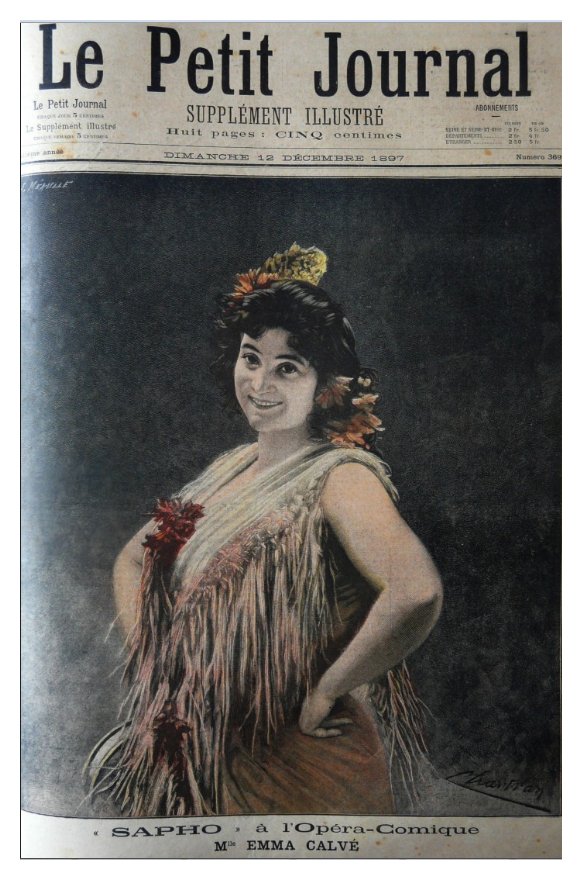

Emma Calvé, born Rosa Emma Calvet (August 15, 1858 – January 6, 1942), was a French operatic soprano. Calvé was probably the most famous French female opera singer of the Belle Époque. Hers was an international career, and she sang regularly at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, and the Royal Opera House, London. Calvé was born on August 15, 1858, in Decazeville, Aveyron. Her birth name was Rosa Emma Calvet. Her father, Justin Calvet, was a civil engineer. She spent her childhood at first in Spain with her parents, then in different convent schools in Roquefort and Tournemire (Aveyron). After her parents separated, she moved with her mother to Paris. There she attempted to enter the Paris Conservatory, while she studied singing under Jules Puget. She started learning music in Paris from Mathilde Marchesi, a retired German mezzo-soprano and Manuel García. She made a tour of Italy, where she saw the famous actress Eleonora Duse, whose impersonations made a deep impression on the young singer. She trained herself in stage craft and gesture by closely observing Duse's performances. Her operatic debut occurred on September 23, 1881, in Gounod's Faust at Brussels' La Monnaie. Later she sang at La Scala in Milan, and also at the principal theatres of Naples, Rome, and Florence. Returning to Paris in 1891, she created the part of Suzel in L'amico Fritz by Pietro Mascagni, playing and singing the role later at Rome. Because of her great success in it, she was chosen to appear as Santuzza in the French premiere of Cavalleria rusticana, which was viewed as one of her greatest parts. She repeated her success in it in London. Her next triumph was Bizet's Carmen. Before beginning the study of this part, she went to Spain, learned the Spanish dances, mingled with the people and patterned her characterization after the cigarette girls whom she watched at their work and at play. In 1894, she made her appearance in the role at the Opéra-Comique, Paris. The city's opera-goers immediately hailed her as the greatest Carmen that had ever appeared, a verdict other cities would later echo. She had had many famous predecessors in the role, including Adelina Patti, Minnie Hauk and Célestine Galli-Marié, but critics and musicians agreed that in Calvé they had found their ideal of Bizet's cigarette girl of Seville. Calvé first appeared in America in the season of 1893–1894 as Mignon. She would make regular visits to the country, both in grand opera and in concert tours. After making her Metropolitan Opera debut as Santuzza, she went on to appear a total of 261 times with the company between 1893 and 1904. She created the part of Anita, which was written for her, in Massenet's La Navarraise in London in 1894 and sang Sapho in an opera written by the same composer.

She sang Ophélie in Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet in Paris in 1899, but the part was not suited to her and she dropped it. She appeared with success in many roles, among them, as the Countess in The Marriage of Figaro, the title role in Félicien David's Lalla-Rookh, as Pamina in The Magic Flute, and as Camille in Hérold's Zampa, but she is best known as Carmen. Calvé developed an interest in the paranormal and was once engaged to the occult author Jules Bois. Calvé wrote of Swami Vivekananda in her autobiography: "[He] truly walked with God, a noble being, a saint, a philosopher and a true friend. His influence upon my spiritual life was profound [...] my soul will bear him eternal gratitude". She also visited Belur Math, Swami Vivekananda's tribute to his guru Ramakrishna Paramahansa. She said of this visit and her association with the monks there: "The hours that I spent with these gentle philosophers have remained in my memory as a time apart. These beings – pure, beautiful and remote seemed to belong to another universe, a better and wiser world" Swami Vivekananda wrote of Calvé: She was born poor but by her innate talents, prodigious labour and diligence, and after wrestling against much hardship, she is now enormously rich and commands respect from kings and emperors....The rare combination of beauty, youth, talents, and "divine" voice has assigned Calve the highest place among the singers of the West. There is, indeed, no better teacher than misery and poverty. That constant fight against the dire poverty, misery, and hardship of the days of her girlhood, which has led to her present triumph over them, has brought into her life a unique sympathy and a depth of thought with a wide outlook.

[More about Emma Calvé can be seen in the biography of her protege, Edna Darch, on the following page] |

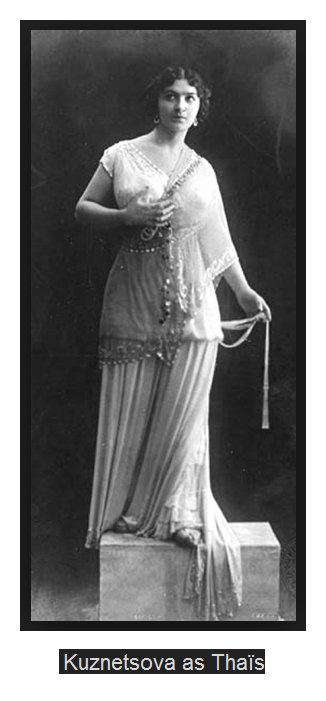

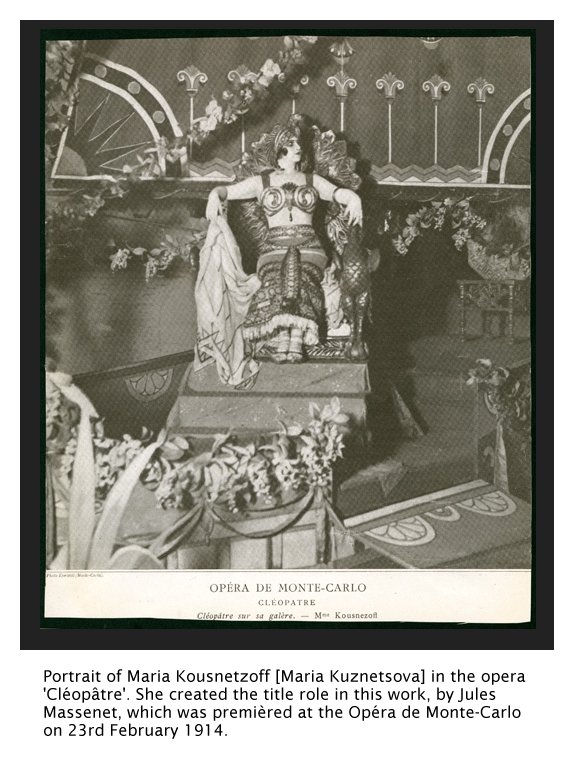

Maria

Nikolayevna Kuznetsova (1880 – April 25, 1966) (Russian: Мария Николаевна

Кузнецова, also spelled Maria Kuznetsova-Benois, Ukrainian: Марія Нiколаевна

Кузнецова), was a famous 20th century Russian Empire and Soviet opera singer

and dancer. Prior to the Revolution, Kuznetsova was one of the most celebrated opera singers

in Imperial Russia, having worked with Richard Strauss, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

and Jules Massenet. She was frequently paired with Feodor Chaliapin. After

leaving Russia in 1917, Kuznetsova continued to perform for another thirty

years abroad before retiring.

Prior to the Revolution, Kuznetsova was one of the most celebrated opera singers

in Imperial Russia, having worked with Richard Strauss, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

and Jules Massenet. She was frequently paired with Feodor Chaliapin. After

leaving Russia in 1917, Kuznetsova continued to perform for another thirty

years abroad before retiring.Kuznetsova was born in 1880, in Odessa, Ukraine, the daughter of portraitist Nikolai Kuznetsov. Kuznetsova's mother was descended from a distinguished family of scientists and intellectuals of Romanian and Russo-Jewish descent. Her maternal grandmother, Emilia (Nevakhovich) Metchnikoff, was the daughter of Lev Nevakhovich (1776-1831), a Russo-Jewish author, translator, and founder of the Haskalah movement in Russia. Emilia married a Guards officer, Ilya Metchnikoff, and had two sons; the Nobel Prize-winning microbiologist Élie Metchnikoff and the sociologist Lev Metchnikoff. Kuznetsova's great-uncles Mikhail and Aleksandr Nevakhovich also had successful careers. Mikhail was a cartoonist and founder of Russia's first satirical magazine, Mish-Mash (Eralash). Aleksandr was a playwright and served as repertory director of Imperial Theaters in Saint Petersburg during the reign of Nicholas I. Kuznetsova initially studied ballet in Saint Petersburg, Russia, but abandoned dancing to study music with the baritone Joachim Tartakov. Kuznetsova was a lyrical soprano with a clear and beautiful singing voice. She also possessed notable talent as an actress. Igor Stravinsky described her as "very appetizing to look at as well as to hear". She initially debuted at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory as Tatiana in Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin in 1904. Kuznetsova debuted for a second time in 1905 at the Mariinsky Theatre as Marguérite in Charles Gounod's Faust. One night, not long after her Mariinsky debut, a dispute erupted in the theater's lobby between students and army officers while Kuznetsova was singing the role of Elsa in Wagner's Lohengrin. Before panic ensued, an unfazed Kuznetsova interrupted the performance, and she then quickly calmed the crowd by leading everyone in a rousing rendition of the Russian national anthem God Save The Tsar! She remained at the Mariinsky as soloist for twelve years until the Revolution in 1917. During her lengthy career, Kuznetsova originated several roles including Fevroniya in Rimsky-Korsakov's The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya, the title role in Massenet's Cléopâtre, Woglinde in the first Russian production of Wagner's Das Rheingold and Fausta in another Massenet creation, Roma. Other signature roles included Oksana in Tchaikovsky's Cherevichki, Thaïs in Massenet's Thaïs, Violetta in Verdi's La traviata, The Snow Maiden in Rimsky-Korsakov's The Snow Maiden, Mimi in Puccini's La bohème, Antonida in Glinka's A Life for the Tsar, Lyudmila in Ruslan and Ludmila and Tamara in Anton Rubinstein's The Demon. Kuznetsova, eventually, developed a sizable following abroad; making her Paris Opera debut in 1908 and her London debut at Covent Garden in 1909. During this period, she appeared in Emmanuel Chabrier's Gwendoline (1910) and Jules Massenet's Roma (1912). In 1916, Kuznetsova made her American debut, performing in New York and Chicago. In New York she caused a sensation, performing with the Manhattan Opera Company in the first American production of Cleopatre.