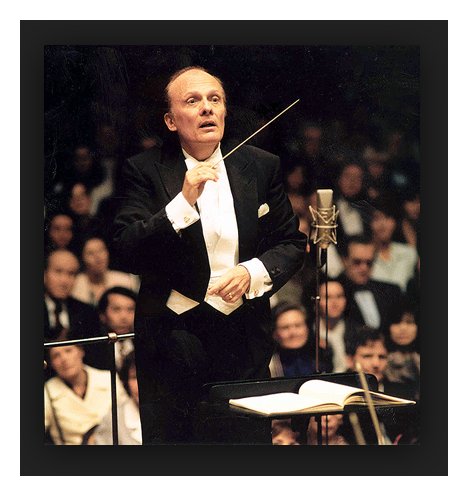

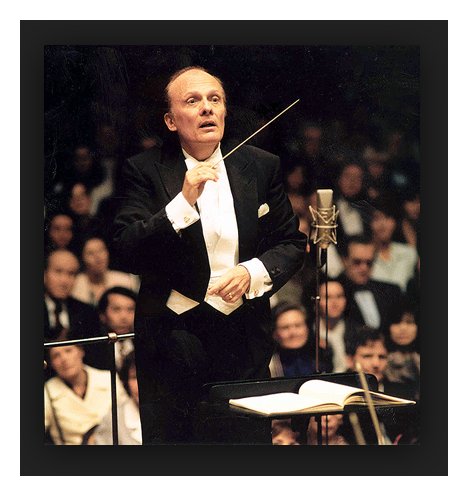

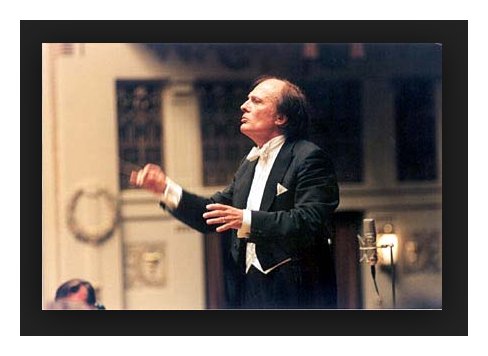

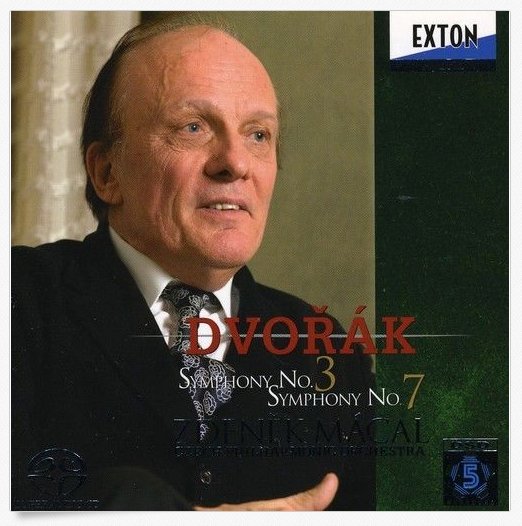

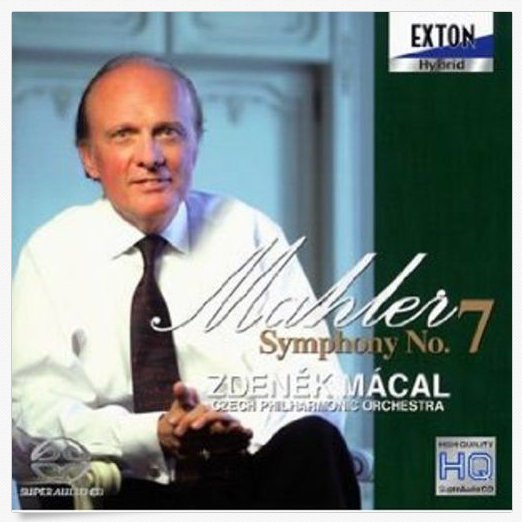

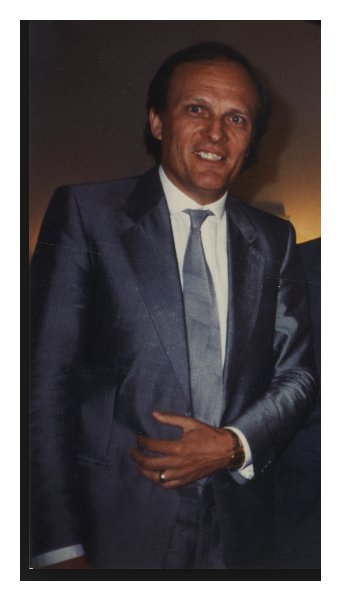

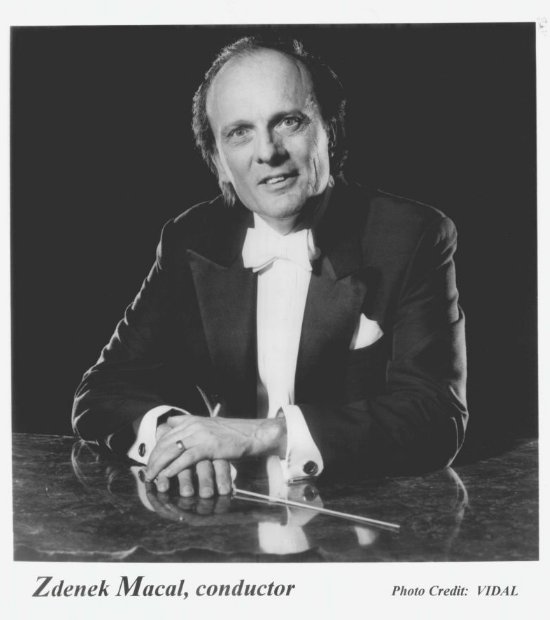

Born in Brno, Czechoslovakia, Zdenek Macal

is now an American citizen. At the age of four he began violin studies

with his father. He went on to study conducting at the Brno

Conservatory and then at the Janácek Academy of Music, where he

graduated with highest honors in 1960. Zdenek Macal's previous

positions include Music Directorships of the Czech Philharmonic

(2003-2007), the New Jersey Symphony (1993-2002), the Milwaukee

Symphony Orchestra (1986-1993), the Cologne Radio Symphony and the

Radio Orchestra of Hannover. He has also served as Chief Conductor of

the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Principal Conductor of Chicago's Grant

Park Summer Festival and Principal Conductor of the Prague Symphony

Orchestra, where he conducted both symphonic concerts and operatic

performances. He first received international attention by winning two

prestigious contests, the 1965 International Conducting Competition in

Besançon, France, and the 1966 Dmitri Mitropoulos Competition in

New York, chaired by Leonard Bernstein. In May, 1998, the Westminster

Choir College honored Maestro Macal with an honorary doctorate. Born in Brno, Czechoslovakia, Zdenek Macal

is now an American citizen. At the age of four he began violin studies

with his father. He went on to study conducting at the Brno

Conservatory and then at the Janácek Academy of Music, where he

graduated with highest honors in 1960. Zdenek Macal's previous

positions include Music Directorships of the Czech Philharmonic

(2003-2007), the New Jersey Symphony (1993-2002), the Milwaukee

Symphony Orchestra (1986-1993), the Cologne Radio Symphony and the

Radio Orchestra of Hannover. He has also served as Chief Conductor of

the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Principal Conductor of Chicago's Grant

Park Summer Festival and Principal Conductor of the Prague Symphony

Orchestra, where he conducted both symphonic concerts and operatic

performances. He first received international attention by winning two

prestigious contests, the 1965 International Conducting Competition in

Besançon, France, and the 1966 Dmitri Mitropoulos Competition in

New York, chaired by Leonard Bernstein. In May, 1998, the Westminster

Choir College honored Maestro Macal with an honorary doctorate. A respected musical force, conductor Zdenek Macal is renowned in the world of classical music for his masterful interpretations and graceful conducting style. He has guest conducted over 160 orchestras worldwide, including the Berlin Philharmonic, the Royal Philharmonic, the London Symphony Orchestra, the London Philharmonic, the Orchestre de Paris, the Orchestre National de France, the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, the Czech Philharmonic, the Vienna Symphony, the Orchestra della Scala, the Stockholm Philharmonic, the Hamburg Philharmonic, the Munich Philharmonic and the NHK Symphony Orchestra in Tokyo. Mr. Macal has also conducted at the Prague National Theater, the Smetana Theater, the Brno Opera, and the opera houses of Cologne, Geneva, Turin and Bologna. He has taken part in major international festivals including those of Vienna, Lucerne, Edinburgh, Prague, Zurich, Besançon, Athens, Montreux and Holland; as well as the Casals Festival in Puerto Rico and the Ravinia, Tanglewood and Wolf Trap festivals in the United States. Since his American debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1972, he has conducted widely throughout North America, regularly leading the New York Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the National Symphony, the St. Louis Symphony, the Pittsburgh Symphony, the Minnesota Orchestra, the Houston Symphony, the New World Symphony and the symphony orchestras of Montreal and Toronto. |

ZM: Yes. In

the beginning I didn’t care so much, but we are doing it now 35

years. My wife and I spend most of the time in the hotels,

especially in the past. Now it’s a little bit better because we

have the house in Milwaukee. I spend about fifteen weeks with

Milwaukee Symphony, so we are now in our house where we have a little

space. We have the main residence in California, so it’s not

exactly ten months in the hotel. It was a few years ago, but

still it is a lot in the hotels. This summer, for example, I go

from the hotel to hotel. I opened the season here, then I went to

Detroit for the Meadow Brook Festival. Then I was in the Wolf

Trap Festival with Washington National Orchestra, and last week I was

with Philadelphia in the Mann Music Center. Then I came back

here. So you have a period of weeks and weeks in the hotels.

ZM: Yes. In

the beginning I didn’t care so much, but we are doing it now 35

years. My wife and I spend most of the time in the hotels,

especially in the past. Now it’s a little bit better because we

have the house in Milwaukee. I spend about fifteen weeks with

Milwaukee Symphony, so we are now in our house where we have a little

space. We have the main residence in California, so it’s not

exactly ten months in the hotel. It was a few years ago, but

still it is a lot in the hotels. This summer, for example, I go

from the hotel to hotel. I opened the season here, then I went to

Detroit for the Meadow Brook Festival. Then I was in the Wolf

Trap Festival with Washington National Orchestra, and last week I was

with Philadelphia in the Mann Music Center. Then I came back

here. So you have a period of weeks and weeks in the hotels. ZM: You cannot

separate these two things. If you should go up artistically you

need the money, and today you cannot just leave it on

administration. You cannot leave it on the executive director

where people on the staff just say, “Go and raise the money.”

They tried; everybody tried very hard, but I know from my experience

that the musical director can do a lot. This is my experience

with Milwaukee and everywhere for the financial situation because you

are, as conductor or as Musical Director, you are more present.

You are more visible, so the people respond to you more

generously. If you go to a party as executive director of the

orchestra, or if you talk to the people, they try to help you.

But if they go to my concerts for a while and they see me on stage, you

are more present. If I use the same words I can get a faster

result and better result. So I do it! It’s very easy to say

the management should do it, but today it a tough job.

ZM: You cannot

separate these two things. If you should go up artistically you

need the money, and today you cannot just leave it on

administration. You cannot leave it on the executive director

where people on the staff just say, “Go and raise the money.”

They tried; everybody tried very hard, but I know from my experience

that the musical director can do a lot. This is my experience

with Milwaukee and everywhere for the financial situation because you

are, as conductor or as Musical Director, you are more present.

You are more visible, so the people respond to you more

generously. If you go to a party as executive director of the

orchestra, or if you talk to the people, they try to help you.

But if they go to my concerts for a while and they see me on stage, you

are more present. If I use the same words I can get a faster

result and better result. So I do it! It’s very easy to say

the management should do it, but today it a tough job. ZM: It’s

different. There are many things that are different from being

inside. First there is the whole acoustic problem outside of

amplification, larger audience, and the space around the

audiences. When I came here in the beginning, I was very

disturbed with the noise all around. Sometimes it disturbed my

concentration so that I was thinking I cannot go ahead. We are on

the corner, so there is the street noise, and there are noises from the

lake. Several times the noise is coming from the air, the

airplanes. This happened just last night a few times, and mostly

they are coming in the softest places. But I learned one thing

over the years — that simply I am not any more

disturbed by these noises. Sometimes I don’t even hear

them. I concentrate only on the sound which is in the

shell. So I can now eliminate the sounds outside, and even if it

is a helicopter is coming, like last night at a very soft moment.

I knew that it was there, but I just felt the noise. There was

some noise there, but my concentration was really on the music in the

shell. So that’s the process for me personally, because as I

said, in the beginning I was quite disturbed. It disturbed your

concentration because on the whole it was mostly absolutely

quiet. So you concentrate only on the sound, and music is

sound. I have done 35 years just listening and absorbing all of

these sounds, so in the beginning when these non-musical sounds came,

they were sounds which I heard and compared. Especially when it

is very humid or hot, the sirens and emergency ambulances are running,

and they don’t care that there is a concert going on. So it’s a

different thing. But one positive thing is that you get much

larger crowds at outdoor concerts. I was just last week in

Philadelphia, and a week before I was in Washington, and a week before

that in Detroit. Everything was outside concerts with huge

audiences, between five and ten thousand people, and they hear every

evening. So many people at the concert! You cannot get this

large audience in the hall, so that’s very positive, that many people

hear the music, that many people participate in the culture

events. On the other hand, outside noises are not

everywhere. For example, Wolf Trap in Washington is in the woods,

so it’s separated completely, and the Mann Music Center is close to the

city, but it’s in the park. Several of these institutions have

the privilege that they are in some isolated spots. Even if they

are in open areas it is a little more isolated. On the other

hand, the summer concerts, basically,sever are not so serious and so

heavy as the winter season that you really listen and concentrate for

it. Very often the summer concerts are combined with picnics and

the family together and friends together, and everything is more

relaxed. So if there is some noise and some train is going and

some siren, okay. So what? We have nice evening, we have

nice weather, we have stars overhead in the sky. It’s a different

atmosphere, but the thing is that you have some kind of cultural

experience. One day, some people who go to summer concerts will

miss this experience during the winter and say, “Gosh, I didn’t hear

for a long time Beethoven or Brahms! Let’s go downtown to the

symphony to a classical concert,” and that’s positive.

ZM: It’s

different. There are many things that are different from being

inside. First there is the whole acoustic problem outside of

amplification, larger audience, and the space around the

audiences. When I came here in the beginning, I was very

disturbed with the noise all around. Sometimes it disturbed my

concentration so that I was thinking I cannot go ahead. We are on

the corner, so there is the street noise, and there are noises from the

lake. Several times the noise is coming from the air, the

airplanes. This happened just last night a few times, and mostly

they are coming in the softest places. But I learned one thing

over the years — that simply I am not any more

disturbed by these noises. Sometimes I don’t even hear

them. I concentrate only on the sound which is in the

shell. So I can now eliminate the sounds outside, and even if it

is a helicopter is coming, like last night at a very soft moment.

I knew that it was there, but I just felt the noise. There was

some noise there, but my concentration was really on the music in the

shell. So that’s the process for me personally, because as I

said, in the beginning I was quite disturbed. It disturbed your

concentration because on the whole it was mostly absolutely

quiet. So you concentrate only on the sound, and music is

sound. I have done 35 years just listening and absorbing all of

these sounds, so in the beginning when these non-musical sounds came,

they were sounds which I heard and compared. Especially when it

is very humid or hot, the sirens and emergency ambulances are running,

and they don’t care that there is a concert going on. So it’s a

different thing. But one positive thing is that you get much

larger crowds at outdoor concerts. I was just last week in

Philadelphia, and a week before I was in Washington, and a week before

that in Detroit. Everything was outside concerts with huge

audiences, between five and ten thousand people, and they hear every

evening. So many people at the concert! You cannot get this

large audience in the hall, so that’s very positive, that many people

hear the music, that many people participate in the culture

events. On the other hand, outside noises are not

everywhere. For example, Wolf Trap in Washington is in the woods,

so it’s separated completely, and the Mann Music Center is close to the

city, but it’s in the park. Several of these institutions have

the privilege that they are in some isolated spots. Even if they

are in open areas it is a little more isolated. On the other

hand, the summer concerts, basically,sever are not so serious and so

heavy as the winter season that you really listen and concentrate for

it. Very often the summer concerts are combined with picnics and

the family together and friends together, and everything is more

relaxed. So if there is some noise and some train is going and

some siren, okay. So what? We have nice evening, we have

nice weather, we have stars overhead in the sky. It’s a different

atmosphere, but the thing is that you have some kind of cultural

experience. One day, some people who go to summer concerts will

miss this experience during the winter and say, “Gosh, I didn’t hear

for a long time Beethoven or Brahms! Let’s go downtown to the

symphony to a classical concert,” and that’s positive. ZM: That’s a

complicated process. One criterion is that we should have the

season quite variable; it should be different composers there. So

first you start and decide what should be on the program.

Basically it should be some Beethoven, some Brahms, from these big

classics, and then it should be some composers that are less frequently

played, like Bohuslav Martinů or Vieuxtemps. Then there are the

contemporary composers, American or worldwide. So you have now

the range of the works which you should put on the whole season, but

you must build every single program for itself. The process is

quite complicated, and it takes me quite a long time. I am

thinking about the programs several seasons ahead, and then I change my

mind and you modulate it. It takes a long time because there are

many components. It’s not easy to say it in five minutes.

Then you have the soloists, and they play some specific repertory

because not everybody plays the same and not everybody plays

everything. You also have some guest conductors and they have

their repertoire. So if we need this and this concerto, the

soloist maybe has not it in their repertoire. So you must ask

what he or she has.

ZM: That’s a

complicated process. One criterion is that we should have the

season quite variable; it should be different composers there. So

first you start and decide what should be on the program.

Basically it should be some Beethoven, some Brahms, from these big

classics, and then it should be some composers that are less frequently

played, like Bohuslav Martinů or Vieuxtemps. Then there are the

contemporary composers, American or worldwide. So you have now

the range of the works which you should put on the whole season, but

you must build every single program for itself. The process is

quite complicated, and it takes me quite a long time. I am

thinking about the programs several seasons ahead, and then I change my

mind and you modulate it. It takes a long time because there are

many components. It’s not easy to say it in five minutes.

Then you have the soloists, and they play some specific repertory

because not everybody plays the same and not everybody plays

everything. You also have some guest conductors and they have

their repertoire. So if we need this and this concerto, the

soloist maybe has not it in their repertoire. So you must ask

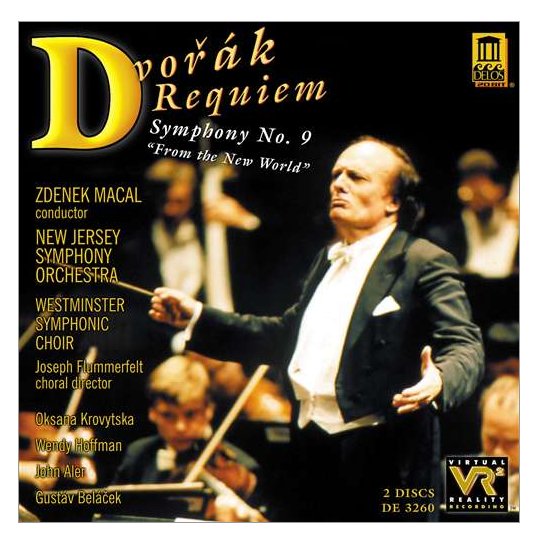

what he or she has. ZM: No, not at

all. No, no, no. The recording for me is the end product,

and is the result of my experience with the work and with the composer

in the past. For example, the New

World Symphony of Dvořák I conducted over 100

times. Last year in Vienna it was my 100th performance, and some

other symphonies go over 50 performances. During these many

performances you change a little, a few details, and you are waiting

for the result to hear how it works. Sometimes you feel that’s

good, it works. Or this tempo is too slow; it should be a little

faster. It should be a little slower here. It should be

more dynamic here; more accent here. It is not exactly

experiment, but it’s just working on the details. Over the years,

when I am working with these works, we can say the better I know

them. Some Beethoven symphonies I have done seventy or eighty

performances. You just try to see the music from a little

slightly different corner, and you’ve got to see if it works or

not. Then you go back or you develop again. So over these

many performances, it’s never final, but you develop your final

version. It means even if I change a few details in every

performance, the main, the ground line, the ground performance is

there, is fixed. Then I can go to the studio and record it.

I don’t like to do things just for the recording, to just learn some

piece and I record it. If you make the recordings, they stay for

the case sometimes for twenty or twenty-five years. It’s your

calling card, your presentation, so if I don’t know the work well, it

is better I don’t do it. With Milwaukee, we started the

recordings and everybody was surprised not only with the high level of

the orchestra playing, but also of the performance, of the

interpretation. Of course I started with Dvořák, which is

very familiar to me, which is also now very familiar to the Milwaukee

Symphony Orchestra. I am now four years as Music Director and one

year principal guest, so the orchestra knows which way they should play

with me. We came to a point that I was satisfied with the results

and we could put it on the CD. We get very positive response from

everywhere, not only with the Dvořák recordings, but also the

Beethoven symphonies. I am very happy about this because when I

came to Milwaukee I started to go systematically through them. We

played every year two or three symphonies, and that’s important from

the education point of view. We play every year for a few years

in the summer the Beethoven symphonies in the Marcus Amphitheater,

which is about 9,000 covered seats. It’s a beautiful

facility. So we are working systematically, the same orchestra,

the same conductor and same direction on one composer, so when we

recorded Beethoven symphonies, I knew that it’s a big task. Every

big orchestra, every greatest orchestra in the world recorded the

Beethoven symphonies. But we took the risk and we recorded them,

and we got very positive response from the critics around the whole

United States. Some people are thinking, “What is the Milwaukee

Symphony?” They didn’t know much about the quality; it wasn’t

very exposed.

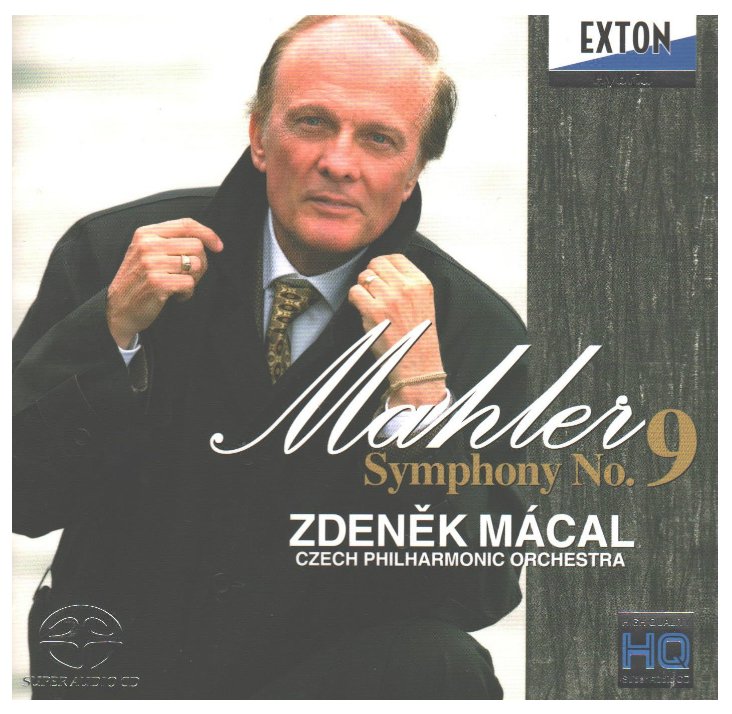

ZM: No, not at

all. No, no, no. The recording for me is the end product,

and is the result of my experience with the work and with the composer

in the past. For example, the New

World Symphony of Dvořák I conducted over 100

times. Last year in Vienna it was my 100th performance, and some

other symphonies go over 50 performances. During these many

performances you change a little, a few details, and you are waiting

for the result to hear how it works. Sometimes you feel that’s

good, it works. Or this tempo is too slow; it should be a little

faster. It should be a little slower here. It should be

more dynamic here; more accent here. It is not exactly

experiment, but it’s just working on the details. Over the years,

when I am working with these works, we can say the better I know

them. Some Beethoven symphonies I have done seventy or eighty

performances. You just try to see the music from a little

slightly different corner, and you’ve got to see if it works or

not. Then you go back or you develop again. So over these

many performances, it’s never final, but you develop your final

version. It means even if I change a few details in every

performance, the main, the ground line, the ground performance is

there, is fixed. Then I can go to the studio and record it.

I don’t like to do things just for the recording, to just learn some

piece and I record it. If you make the recordings, they stay for

the case sometimes for twenty or twenty-five years. It’s your

calling card, your presentation, so if I don’t know the work well, it

is better I don’t do it. With Milwaukee, we started the

recordings and everybody was surprised not only with the high level of

the orchestra playing, but also of the performance, of the

interpretation. Of course I started with Dvořák, which is

very familiar to me, which is also now very familiar to the Milwaukee

Symphony Orchestra. I am now four years as Music Director and one

year principal guest, so the orchestra knows which way they should play

with me. We came to a point that I was satisfied with the results

and we could put it on the CD. We get very positive response from

everywhere, not only with the Dvořák recordings, but also the

Beethoven symphonies. I am very happy about this because when I

came to Milwaukee I started to go systematically through them. We

played every year two or three symphonies, and that’s important from

the education point of view. We play every year for a few years

in the summer the Beethoven symphonies in the Marcus Amphitheater,

which is about 9,000 covered seats. It’s a beautiful

facility. So we are working systematically, the same orchestra,

the same conductor and same direction on one composer, so when we

recorded Beethoven symphonies, I knew that it’s a big task. Every

big orchestra, every greatest orchestra in the world recorded the

Beethoven symphonies. But we took the risk and we recorded them,

and we got very positive response from the critics around the whole

United States. Some people are thinking, “What is the Milwaukee

Symphony?” They didn’t know much about the quality; it wasn’t

very exposed. ZM: In the

contemporary music I can say William Schuman’s Third Symphony is such a joy!

[See my Interview

with William Schuman.] I don’t see a big difference between

conducting this work and the Beethoven Third Symphony, the Eroica. I believe in every

single piece which I conduct, because if I don’t believe in this music

I will not do it. First, I must believe that what I conduct is

good. So first I pick up the works which I believe are

good. Second, I do the works which I believe that I can animate

part of the music which maybe is not the strongest, but still has

substance, and I can discover the strongest side. Or I can show

the work from the best side. To be specific, Richard Strauss is a

great composer, one really from the greatest list. He has written

so many operas and so many big symphony works which are great, but they

are long. In something over 40 minutes, not all 40 minutes are

first-rate. There are moments that are a little odd. They

are part of the great composer, but they need some help. So it’s

a challenge for you. Just don’t do it in a boring way. Try

turning it; maybe have a different balance or a different color or a

different tempo. It’s your challenge; it’s your discovery how you

can work with it. If you are emotional, maybe you can turn the

dial on the other side and just show it from a different light.

It’s like with a picture. Maybe the angle is wrong, so try from

the other side. Maybe that looks better, so it is a good

composition, too. Maybe it seems just to me that this part is not

strong enough because I feel it the wrong way, or maybe I interpret it

a wrong way.

ZM: In the

contemporary music I can say William Schuman’s Third Symphony is such a joy!

[See my Interview

with William Schuman.] I don’t see a big difference between

conducting this work and the Beethoven Third Symphony, the Eroica. I believe in every

single piece which I conduct, because if I don’t believe in this music

I will not do it. First, I must believe that what I conduct is

good. So first I pick up the works which I believe are

good. Second, I do the works which I believe that I can animate

part of the music which maybe is not the strongest, but still has

substance, and I can discover the strongest side. Or I can show

the work from the best side. To be specific, Richard Strauss is a

great composer, one really from the greatest list. He has written

so many operas and so many big symphony works which are great, but they

are long. In something over 40 minutes, not all 40 minutes are

first-rate. There are moments that are a little odd. They

are part of the great composer, but they need some help. So it’s

a challenge for you. Just don’t do it in a boring way. Try

turning it; maybe have a different balance or a different color or a

different tempo. It’s your challenge; it’s your discovery how you

can work with it. If you are emotional, maybe you can turn the

dial on the other side and just show it from a different light.

It’s like with a picture. Maybe the angle is wrong, so try from

the other side. Maybe that looks better, so it is a good

composition, too. Maybe it seems just to me that this part is not

strong enough because I feel it the wrong way, or maybe I interpret it

a wrong way.  ZM: I don’t think

so. It will not be so different even if we have the tapes and all

the recording possibilities. What we have today is that more

people can listen relatively very easily and in a relatively cheap way

to much more music, and they can select. But they will make their

selection. You do selection, I do selection, because we like

something and we dislike something. In the end, if we will listen

to some tapes of this composer and another composer, and if somebody

will be here with us who will not know much about the music —

definitely less than we do — when we talk about this we will all be

very close. It doesn’t matter how many people; we will be very

close in some feelings. We will differ in a few things, but

generally you will say, “Okay, I like this piece but I don’t like that

piece,” and I will tell you maybe why, because that’s my job.

ZM: I don’t think

so. It will not be so different even if we have the tapes and all

the recording possibilities. What we have today is that more

people can listen relatively very easily and in a relatively cheap way

to much more music, and they can select. But they will make their

selection. You do selection, I do selection, because we like

something and we dislike something. In the end, if we will listen

to some tapes of this composer and another composer, and if somebody

will be here with us who will not know much about the music —

definitely less than we do — when we talk about this we will all be

very close. It doesn’t matter how many people; we will be very

close in some feelings. We will differ in a few things, but

generally you will say, “Okay, I like this piece but I don’t like that

piece,” and I will tell you maybe why, because that’s my job.

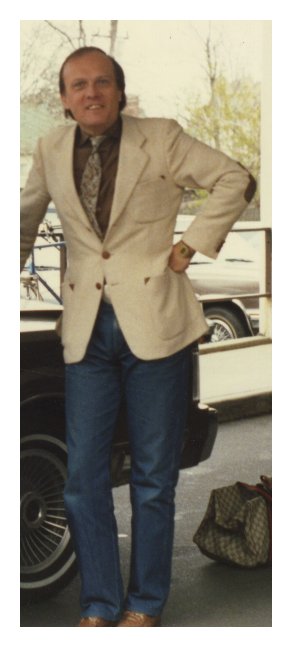

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on July 26,

1990. Segments were used

(with recordings)

on WNIB a month later, and again in 1994 and 1996. It was also

used on WNUR twice in 2012, and on Contemporary Classical Internet

Radio also in 2012. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.