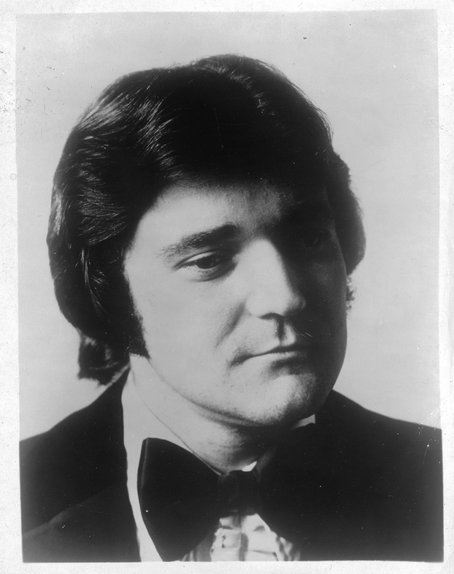

Presenting Tenor Barry McCauley

By Bruce Duffie

[This article originally appeared in the Massenet Newsletter in July, 1987.

For this website presentation, the biography has been added, as well as the photos and links.]

Barry McCauley (June 25, 1950—October 10, 2001) was born in Altoona, PA. He received his BA from Eastern Kentucky University, his MA from Arizona State University. He was a member of the San Francisco Opera Merola Program for two summers, and made his professional debut as Don José with the San Francisco Spring Opera in 1977. The following year he sang the title role in Faust with the San Francisco Opera. Other roles in San Francisco included Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, Ruggero in La Rondine and Pierre in Prokofiev’s War and Peace, conducted by Valery Gerghiev.  His New York City Opera debut came in

1980 with the title role in Gounod’s Faust.

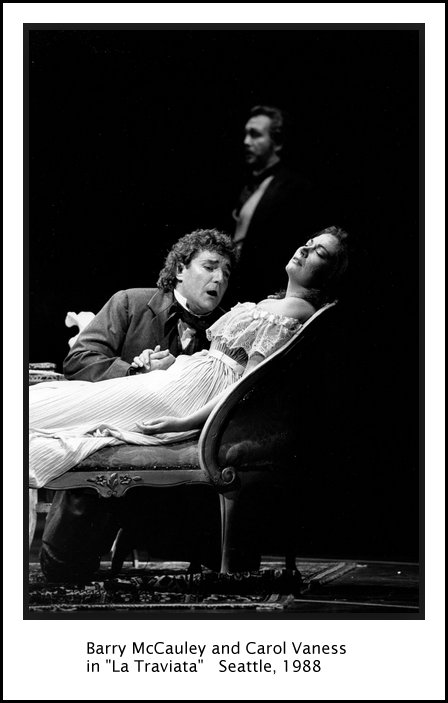

Additional roles with the company included Rodolfo in La Bohème, Alfredo in La Traviata, Roberto Dudley in Maria Stuarda, Nadir in Les Pêcheurs de Perles,

Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly,

Ruggero in La Rondine and

Gerald in Lakmé. His

performance of Edgardo in Lucia di

Lammermoor was telecast nation-wide on “Live From Lincoln

Center” during the 1981-82 season [shown

in photo at right]. His New York City Opera debut came in

1980 with the title role in Gounod’s Faust.

Additional roles with the company included Rodolfo in La Bohème, Alfredo in La Traviata, Roberto Dudley in Maria Stuarda, Nadir in Les Pêcheurs de Perles,

Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly,

Ruggero in La Rondine and

Gerald in Lakmé. His

performance of Edgardo in Lucia di

Lammermoor was telecast nation-wide on “Live From Lincoln

Center” during the 1981-82 season [shown

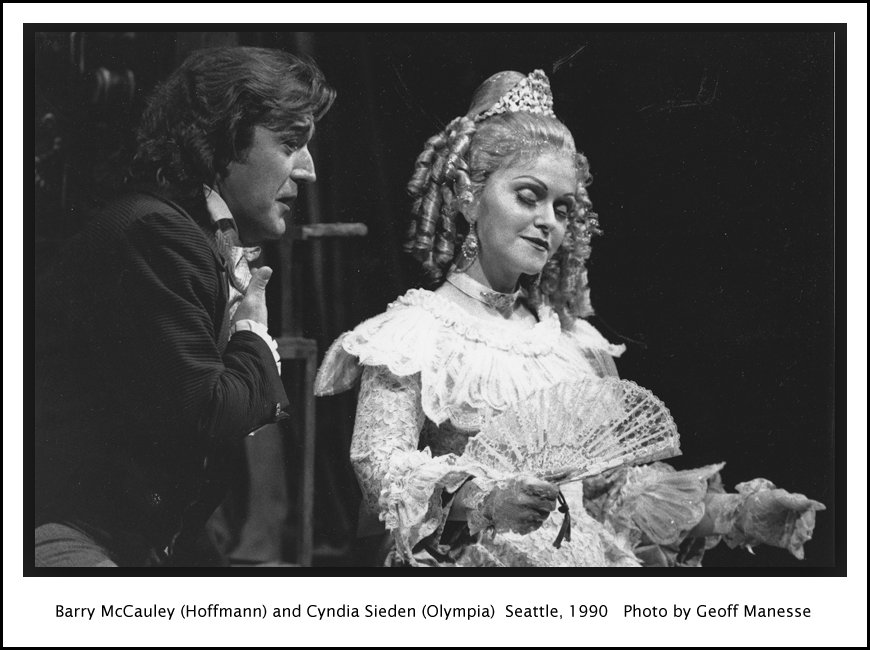

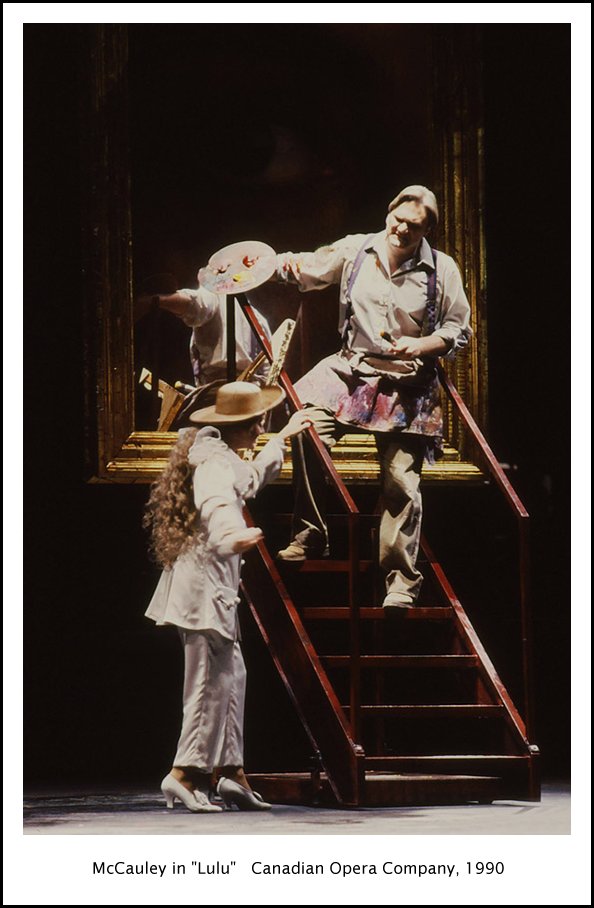

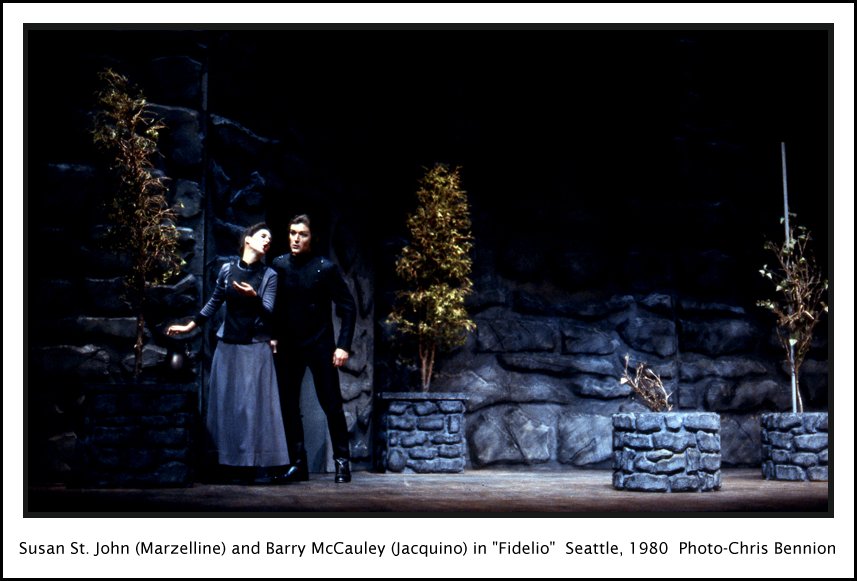

in photo at right].He made his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1986 as Jaquino in Fidelio. He also sang the painter in Lulu, and Cassio in Otello in a gala performance conducted by Carlos Kleiber. His Santa Fe Opera debut was as Wilhelm in Mignon opposite Frederica von Stade. His Lyric Opera of Chicago debut was as Gerald in Lakmé He returned there as Ruggerio in La Rondine with Ileana Cotrubas, and as Loge in Das Rheingold, conducted by Zubin Mehta. McCauley also had a major European career. For the Opéra de Paris he sang Boris in Katya Kabanova, Belmonte in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Lensky in Eugene Onegin, Admete in Alceste, and des Grieux in Manon. At the Netherlands Opera he debuted in La Damnation de Faust, later returning to sing the title role in Parsifal and Hegenback in Catalani’s La Wally. Other important European appearances included Salzburg Festival performances such as Filka Morosov/Luka Kuzmic in From the House of the Dead, conducted by Claudio Abbado, and as Aegisth in Elektra (a role he repeated in concert with the Berlin Philharmonic); a portrayal of Alwa in Köln Opera’s production of Lulu; Andres and the Drum Major in Wozzeck, both at the Teatro la Fenice in Venice; Gregor in The Makropoulos Affair at the Teatro Communale in Bologna; Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni for his debut at Aix-en-Provence; Boris in Katya Kabanova and Don José in Carmen at the Glyndebourne Festival; Idamante in Idomeneo and Belfiore in La finta giardiniera in Brussels; Wilhelm Meister for the Maggio Musicale in Florence; and Hoffmann for the Grand Théâtre de Genève. He was the recipient of the prestigious Richard Tucker Award in 1980. -- [Names which are links

refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD]

|

Coming back to purely vocal considerations,

McCauley seems not to mind the label ‘French

Tenor’. He says there aren’t

that many around, but his is not a specifically ‘French’

style voice. “That type doesn’t

exist any longer, and there’s no one around to

teach it. The closest who still exists is Alfredo Kraus.

He can go up into the high register and do what is called a ‘voix-mixe’,

which is a mixture of voices. It’s not

falsetto or head voice, but a certain technique that was taught in

earlier days. Gedda could do it. At the time I should have

learned it, I was out in the business world and didn’t

have the time to work with my teacher.”

McCauley then added that if he could find someone to teach it, and if

time could be found in his own busy schedule, he’s

be glad to work on the technique. But time is important to this

family man, and as he pointed out, “Once the

ball starts rolling, you go from one job to another with maybe two

weeks in between, and during that time you want to do nothing, or you’re

coaching roles that are coming up. It’s a

shame, but it’s what happens.”

Developing that special technique must be done over years.

Coming back to purely vocal considerations,

McCauley seems not to mind the label ‘French

Tenor’. He says there aren’t

that many around, but his is not a specifically ‘French’

style voice. “That type doesn’t

exist any longer, and there’s no one around to

teach it. The closest who still exists is Alfredo Kraus.

He can go up into the high register and do what is called a ‘voix-mixe’,

which is a mixture of voices. It’s not

falsetto or head voice, but a certain technique that was taught in

earlier days. Gedda could do it. At the time I should have

learned it, I was out in the business world and didn’t

have the time to work with my teacher.”

McCauley then added that if he could find someone to teach it, and if

time could be found in his own busy schedule, he’s

be glad to work on the technique. But time is important to this

family man, and as he pointed out, “Once the

ball starts rolling, you go from one job to another with maybe two

weeks in between, and during that time you want to do nothing, or you’re

coaching roles that are coming up. It’s a

shame, but it’s what happens.”

Developing that special technique must be done over years.

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on

January 5, 1986. The transcription was made and published in the Massenet Newsletter in July,

1987. It was slightly re-edited, the photos, bio, and links were

added, and it was posted on this

website in 2016.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.