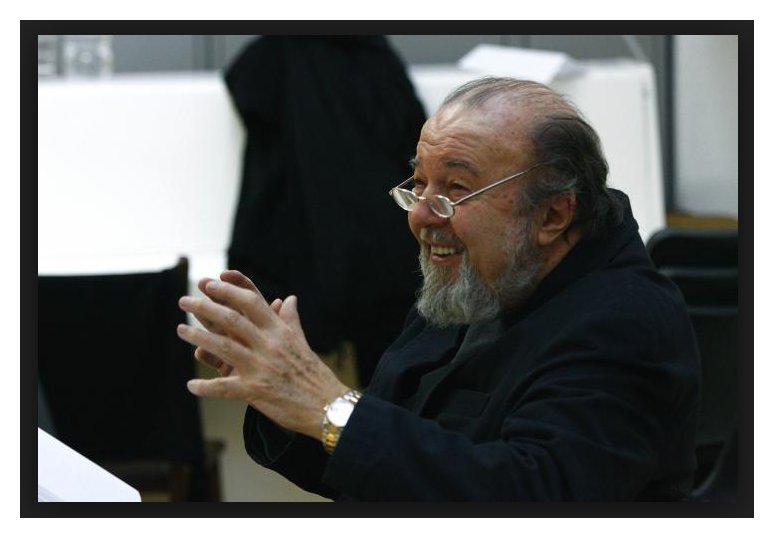

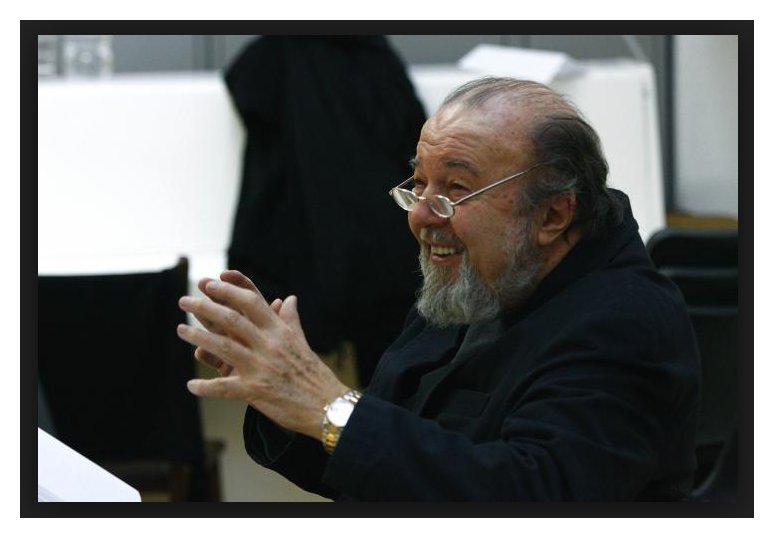

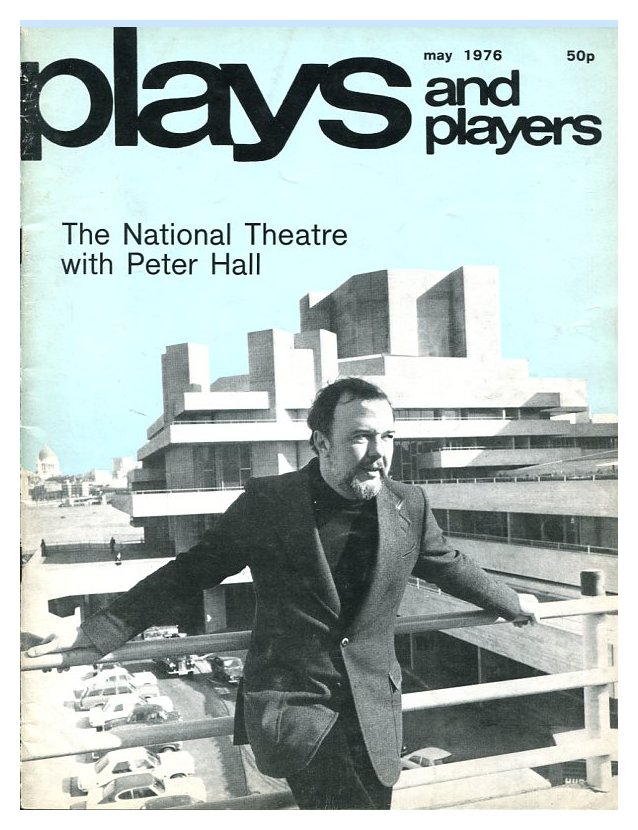

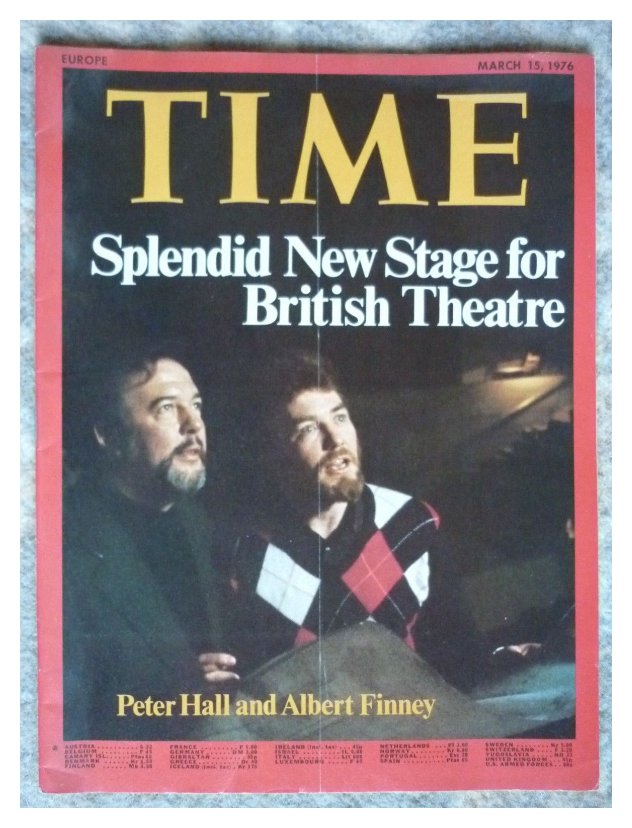

PH: Yes. I founded the Royal Shakespeare Company

in 1960, and ran that for ten years. Then I went to the National Theatre,

and opened the new theaters on the Southbank in 1973. I’m leaving the

National Theatre next year after fifteen years whenever my contract is mercifully

up! [Laughs] Then I shall be more of a freelancer than I suppose

I’ve ever been in my life. I’ve always done quite a lot of outside work,

although running these large organizations is the only way of actually defending

your creative self. It’s a kind of holiday for me to come here and

have nothing to do except The Marriage

of Figaro.

PH: Yes. I founded the Royal Shakespeare Company

in 1960, and ran that for ten years. Then I went to the National Theatre,

and opened the new theaters on the Southbank in 1973. I’m leaving the

National Theatre next year after fifteen years whenever my contract is mercifully

up! [Laughs] Then I shall be more of a freelancer than I suppose

I’ve ever been in my life. I’ve always done quite a lot of outside work,

although running these large organizations is the only way of actually defending

your creative self. It’s a kind of holiday for me to come here and

have nothing to do except The Marriage

of Figaro.| The new Production in Chicago apparently

caught the attention of the press in New York City. Here is a brief

portion of a review . . . . . OPERA: CHICAGO'S LYRIC IN 'MARRIAGE OF FIGARO'

By DONAL HENAHAN, Special to The New York Times Published: December 11, 1987 Metropolitan Opera audiences who know Peter Hall only as the director of two famously lackluster productions, ''Macbeth'' and ''Carmen,'' must have a seriously distorted view of his talents. As often happens, the right man was hired for the wrong jobs. The prolific Englishman's work is more justly represented by his stagings of Mozart operas, particularly for the Glyndebourne Festival, of which he has been artistic director since 1984. In any event, the ''Marriage of Figaro'' that Mr. Hall has produced for his debut season with Lyric Opera of Chicago demonstrates that he is a Mozart man to the bone, one who knows the difference between an ensemble and a collection of singers. (...) |

PH: No, I don’t think I am. When I read Mozart’s

letters or Verdi’s letters or Wagner’s letters, that’s what they were expecting.

They were expecting theater! Too much opera is not about theater, and

it has no meaning. But it’s always been like that and always will be.

There are very few people who can sing and act at the right level as it’s

a terrifyingly difficult thing to do. There are very few great

singer-actors. There are very few conductors who actually have a dramatic

sense, and there are very few directors who have any sense of music.

PH: No, I don’t think I am. When I read Mozart’s

letters or Verdi’s letters or Wagner’s letters, that’s what they were expecting.

They were expecting theater! Too much opera is not about theater, and

it has no meaning. But it’s always been like that and always will be.

There are very few people who can sing and act at the right level as it’s

a terrifyingly difficult thing to do. There are very few great

singer-actors. There are very few conductors who actually have a dramatic

sense, and there are very few directors who have any sense of music. PH: [With a big smile] What happens in the

fourth act indeed! No, I think I shall always pass on that one.

I’ve been asked to do all sorts of things over the years which have not felt

right at the moment that I was asked, or I didn’t feel the way of doing them.

I’ve never done any Puccini, and I should want to do Puccini very much.

I’m going to do Tosca in Los Angeles

in a couple of years’ time, and I’m going to do The Trojans at Maggio Musicale in Florence,

which is a lifelong ambition. I’m going to do Michael Tippett’s new

opera, New Year, in Houston, and

I’m continuing my love affair with Mozart in that I’m doing Così Fan Tutte next year in Los

Angeles, a new Figaro at Glyndebourne

in three years’ time, and then a new Così

Fan Tutte and a new Don Giovanni

also at Glyndebourne because one could keep on doing these pieces.

PH: [With a big smile] What happens in the

fourth act indeed! No, I think I shall always pass on that one.

I’ve been asked to do all sorts of things over the years which have not felt

right at the moment that I was asked, or I didn’t feel the way of doing them.

I’ve never done any Puccini, and I should want to do Puccini very much.

I’m going to do Tosca in Los Angeles

in a couple of years’ time, and I’m going to do The Trojans at Maggio Musicale in Florence,

which is a lifelong ambition. I’m going to do Michael Tippett’s new

opera, New Year, in Houston, and

I’m continuing my love affair with Mozart in that I’m doing Così Fan Tutte next year in Los

Angeles, a new Figaro at Glyndebourne

in three years’ time, and then a new Così

Fan Tutte and a new Don Giovanni

also at Glyndebourne because one could keep on doing these pieces. BD: Didn’t he have his singers come in 1875 to rehearse,

and then in 1876 to rehearse again before the performances?

BD: Didn’t he have his singers come in 1875 to rehearse,

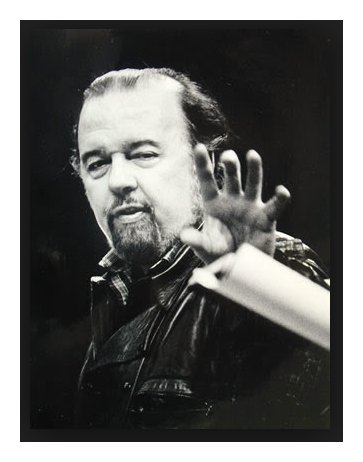

and then in 1876 to rehearse again before the performances? PH: Oh, enormous! I’ve been doing it for thirty

years. I’ve never been anything else. I started directing two

weeks after I left university, and I had my first theater to run at 24!

So I’ve always run theaters, and I’ve always been a director. But I

like directing, and now even more than I started. It’s an enormous

fun.

PH: Oh, enormous! I’ve been doing it for thirty

years. I’ve never been anything else. I started directing two

weeks after I left university, and I had my first theater to run at 24!

So I’ve always run theaters, and I’ve always been a director. But I

like directing, and now even more than I started. It’s an enormous

fun.|

Productions of Sir Peter Hall at Lyric Opera

of Chicago

Marriage of Figaro 1987-88 with Ramey, Ewing, Lott, Raimondi, von Stade,

Korn, Benelli, Kern; Davis,

von Heidecke

1991-92 with Ramey, McLaughlin, Lott, Schimmel, von Stade, Loup, Benelli, Palmer, Futural (Barbarina); Davis, von Heidecke 1997-98 with Terfel, Futural (Susanna), Fleming, Hagegård, Graham, Travis, Davies, Cook; Mehta, Tallchief 2003-04 (Opening Night) with Tigges, Bayrakdarian, Swensen, Mattei, McNeese/Krull, Silvestrelli, Ziegler, Davies; Davis, von Heidecke 2009-10 with Ketelsen, De Neise, Schwanenwilms/Cabell/Majeski, Kwiechen, DiDonato, Silvestrelli, Curnow, Jameson; Davis/Vordoni, Tye Salome 1988-89 with Ewing, Nimsgern, King, Fassbaender, Farina; Slatkin Così fan tutte 1993-94 with Vaness/Magee, Ziegler, Lewis, Black, Rolandi, Desderi; Davis Otello 2001-02 (Opening Night) with Heppner, Fleming/Esperian, Gallo, Kaufmann (Cassio), Davis Midsummer Marriage 2005-06 with Watson, Kaiser/Ramsay, Rose, Tappan, Wyn-Rogers, Arwady, Langan; Davis |

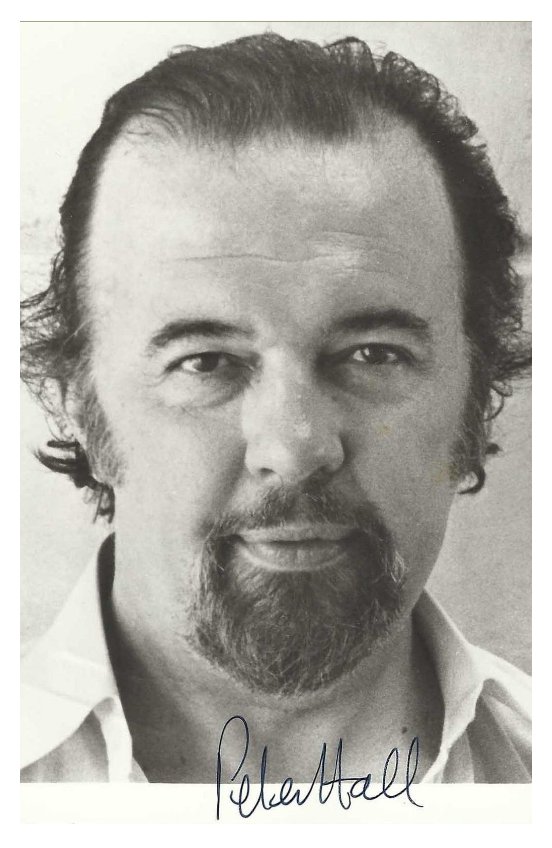

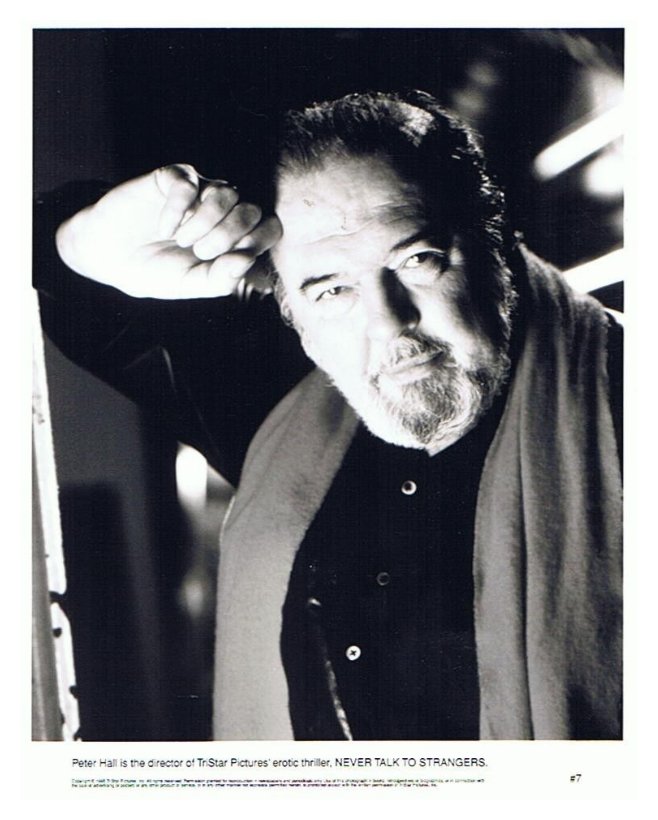

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in a dressing room backstage at the Civic Opera House in Chicago on November 5, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three days later, and again in 1990. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.